Chapter 39 Psychiatric presentations

Mental health presentations to emergency departments are common and encompass a wide variety of issues either as principal reasons for attendance or as important comorbidities. Problems with mental health, drugs and alcohol, social disability and medical illness frequently coexist, complicating assessment, management and disposition. The more common primary mental health presentations include:

TRIAGE

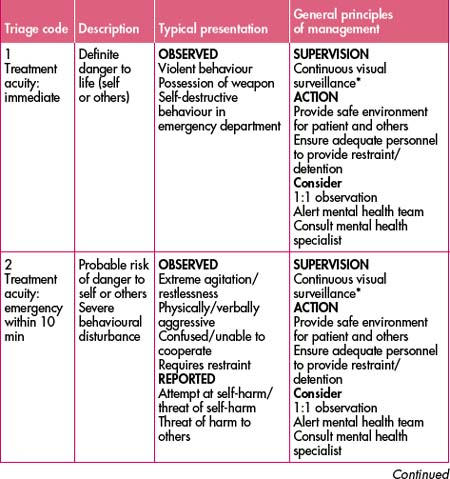

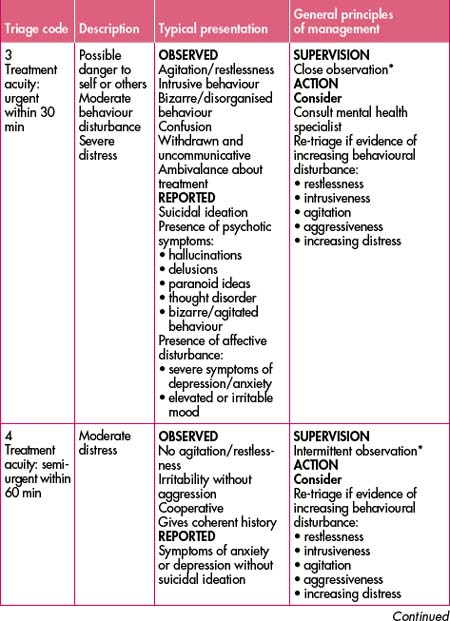

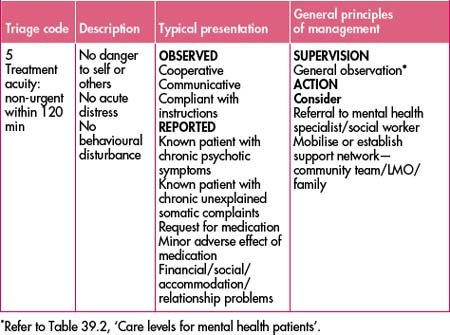

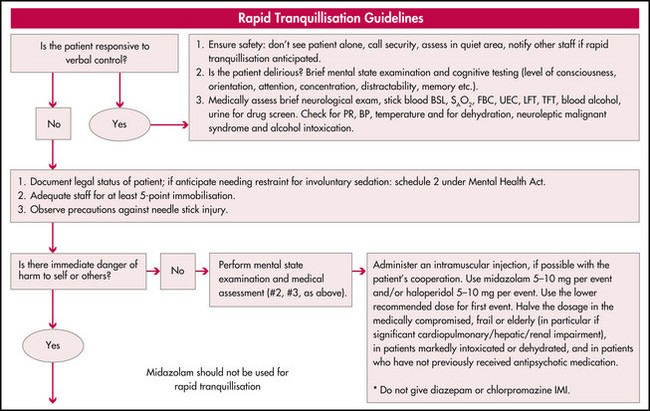

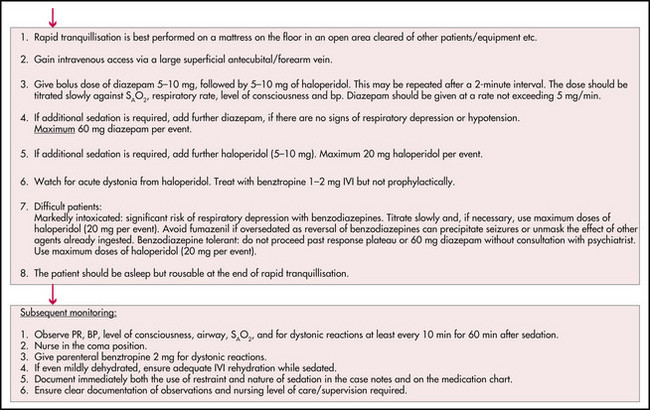

Triage should be performed as with all emergency department patients along standardised lines (see Table 39.1). A team approach for the reception of involuntary patients should involve mental health, medical, nursing, security and other staff working with established and practised protocols. Police, when initially present, should stay until safety and control have been established. A rapid sedation protocol should be used as required (see Figure 39.1).

Interviewing the potentially violent patient needs to be undertaken in a manner that minimises the chances of escalation while maintaining your safety and that of the patient. This is best done in an environment which has at least two exits and which can be observed by other staff (this may need to be done discreetly out of respect for the patient’s privacy). The presence of potential dangers should be considered and appropriate steps taken; furniture should be too heavy to throw and anything that could be used as a weapon (e.g. IV poles) should be removed. Consider removing neckties/necklaces, stethoscopes, pens etc from your person. Tell others where you will be and who you are with. Carry a ‘personal duress alarm’ and make sure you know how to activate it.

The initial contact is aimed at defusing the situation, but this will often depend on elucidating and treating the underlying cause. Therefore, history taking, assessment of mental state and looking for other diagnostic clues should proceed simultaneously. Your approach should be empathic and non-confrontational; avoid making the patient feel verbally (e.g. by using ultimatums) or physically threatened (e.g. by standing over a seated patient or blocking their exit).

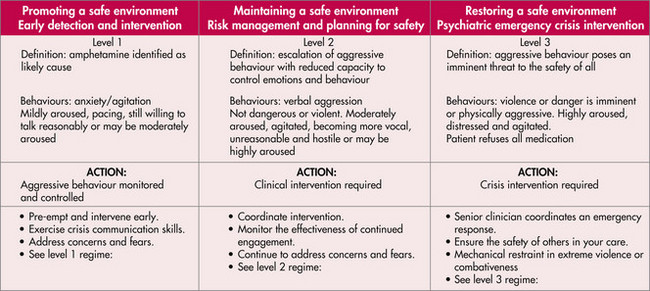

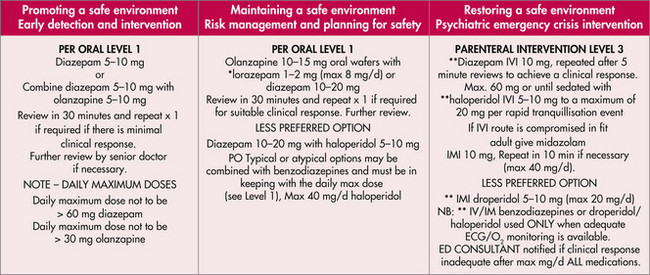

CONTROL OF AGGRESSION

Should this approach fail a ‘show of force’ may be necessary, such as the obvious presence of security/police officers to back up the clinician with the aim being to convince the patient that further escalation is unwise and in the hope that they will then agree to take medication. One person (usually the clinician involved) should lead the staff and interact with the patient. A fallback plan should always be in place at this stage: if the violence/aggression appears to be due to a medical or psychiatric condition and physical/pharmacological restraint is legally justifiable, it should be the next step; if not, the patient/subject should be escorted from the department by security or police.

HISTORY AND ASSESSMENT

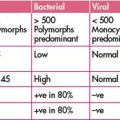

There are many causes of aggressive behaviour, which vary from psychosis and antisocial/borderline personality traits to organic causes such as head injury, delirium, drugs, sepsis and post-ictal states. Use of a Mini Mental State Examination (refer to Table 34.1 in Chapter 34, ‘Geriatric care’) will help to identify cognitive deficits or a possible delirium. It can be especially useful if a change over time can be identified and can also help you decide if the patient is too sedated, sleepy or disorientated to provide a valid history.

INITIAL APPROACH

Establish why this problem requires attention now:

Context is important: why here and why now? Preliminary information gathering can significantly expedite the assessment process. In some instances there may be an existing ‘management plan’. Early enquiries and review of previous presentations or an existing mental health record can reveal valuable information regarding the involvement of other healthcare providers or provide an established working diagnosis.

The mental health interview

Risk of self-harm

Some of the questions that will determine risk of harm to self are:

FURTHER ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

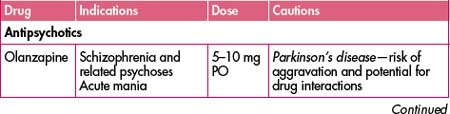

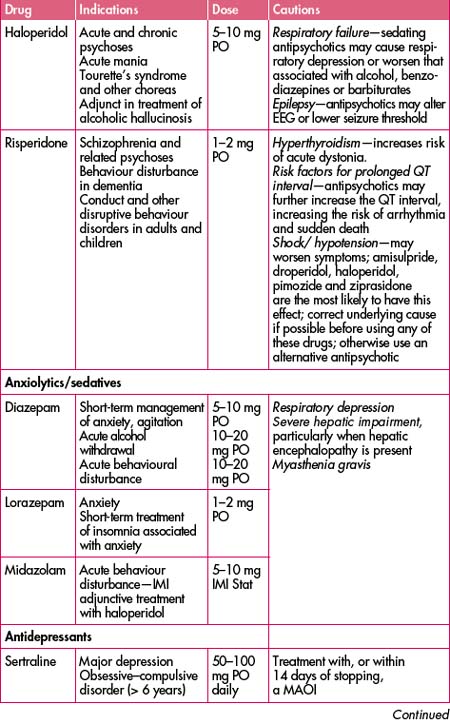

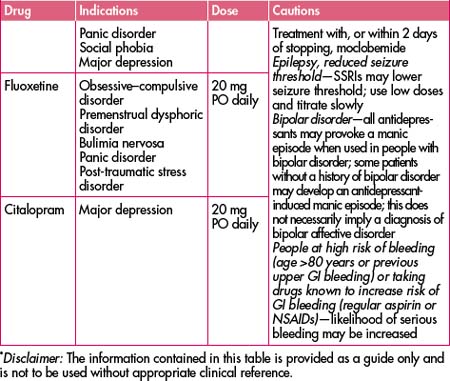

Treating medical issues (e.g. sepsis, pain) may well lead to improvement in mental health symptoms. Management of intoxication or withdrawal states such as with methamphetamine or alcohol (see Figure 39.2) is important. Basic needs such as food and personal hygiene need to be addressed. Psychiatric medication should be instituted (or reinstituted) with care and ideally specialist consultation. A basic understanding of antipsychotics, antidepressants, sedatives and neuroleptics as well as their interactions is required (see Table 39.2).

| Care level 1: visual range within 1 metre |

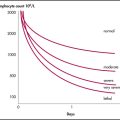

Ideally, use defined criteria to assign a care level to each patient to ensure appropriate supervision and observation (see Table 39.2). Documentation should clearly explain the reasons that sedation and/or restraint were required, and the doses, routes of administration and timing of any medications used. At the earliest possible time, fill out the legal forms (schedules) if indicated.

The mental state examination

The mental status examination is a set of observations made throughout the psychiatric interview. These observations can then be articulated to describe the person’s mental state.

Disposition

When available, admission to a short-stay combined medical and mental health facility (psychiatric emergency care centre) may be an option. These units ideally have joint admission processes under the care of a psychiatrist and an emergency or other physician. Ideally they should have clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria and streamed clinical pathways. Community mental health, GPs, psychiatrists, social workers and drug and alcohol professionals will usually be involved.

Arnold K., Hudson B., Priesz P. Rapid tranquillisation. Sydney: St Vincent’s Hospital; 1999.

Centre for Mental Health. Mental health for emergency departments—a reference guide. NSW Department of Health. amended May 2002. 2001–2002

Mental Health Triage Guidelines. South Eastern Sydney Area Health Service. Area Mental Health Program. 1999.

Slaby A.E. Handbook of psychiatric emergencies, 4th edn. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1994.

Treatment Protocol Project. Management of mental disorders, 2nd edn. Sydney: World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and Substance Abuse; 1997.