Psychiatric disorders of childbirth

Introduction

The relevance of maternal mental health to obstetricians

Childbirth is a substantial risk to mental health, greater than at other times in a woman’s life. There is an elevated incidence of severe mood (affective) disorders postpartum associated with an increased risk of suicide in the early postpartum weeks (Box 14.1).

The prevalence and range of psychiatric conditions in early pregnancy is the same as in the female population of comparable age. Mental illness during pregnancy can cause management problems and effect the pregnancy outcome and fetal and infant development. Women with current mental illness may be taking medication. Stopping medication in pregnancy can lead to relapse that may compromise management. Continuing medication may affect the developing fetus. The obstetrician will be asked to give advice on medication and undertake a risk benefit analysis.

Perinatal psychiatry

Perinatal psychiatric disorders include:

• New onset conditions in previously well women.

• The recurrence of conditions in women who have been well for some time but have a history of a previous illness.

• Relapses or deteriorations in women who are currently ill or who have not fully recovered from a previous illness.

Perinatal psychiatry is also concerned with the effects of maternal illness and treatment on the developing fetus and infant.

Psychiatric medication in pregnancy

Antenatal screening

A family history of bipolar illness is a risk factor for postpartum psychosis. The risk is approximately 3% (compared with 0.2% in the general pregnant population). If the family history is of postpartum onset conditions then the risk is higher; however, between 94% and 97% of women will remain well. Unless the woman is concerned, a positive family history is not necessarily an indication for referral to psychiatric services. However, all should remain vigilant and have a lowered threshold for concern if symptoms develop following delivery.

Substance misusers should be referred to specialized midwives and drug addiction services. They are not appropriately managed by specialized perinatal mental health services or general adult services nor by general practitioners.

It is recommended that the Whooley questions are used:

1. During the past month have you often been bothered by feeling down, hopeless or depressed?

2. During the past month have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

Postnatal psychiatric disorders

Postpartum (puerperal) psychosis

This is the least common and most serious of the postpartum conditions occurring in 2/1000 deliveries in women of all ages, backgrounds and in all cultures and countries in the world. It is commoner in first-time mothers and in older mothers and those who have had emergency caesarean section after a first baby. Risk factors include a family history of bipolar illness, a maternal family history of postpartum psychosis and previous episodes of bipolar illness, schizo-affective disorder or postpartum psychosis (Box 14.2).

The illness is characterized thus:

• Sudden onset in the early days following delivery, deteriorating on a daily basis.

• Half will present within first postpartum week, the majority within 2 weeks and almost all within 3 months of delivery.

• Psychosis, delusions, fear and perplexity, confusion and agitation and sometimes hallucinations.

Postnatal depressive illness

Severe postnatal depression

Women with severe postnatal depressive illness feel guilty, have ideas of worthlessness, lack of enjoyment and lack of spontaneity. They are often preoccupied with ruminative worry and are very anxious (Box 14.3). Intrusive obsessional thoughts of harm coming to their babies and panic attacks are common. Sometimes they are preoccupied by the birth experience and may have some features of obstetric post traumatic stress disorder.

Mild to moderate postnatal depression

This is the commonest postpartum condition. The most important risk factors are psychosocial.

The symptoms will be less severe without the tendency to rapidly deteriorate and worsen and may be very variable with good days and bad days. They will often feel better in company and worse when alone. They may not have the classical sleep disturbance and loss of vitality and pleasure but nonetheless may be distressed by their lack of pleasure and enjoyment in their babies (Box 14.4). Anxiety is a prominent feature.

UK confidential enquiries into maternal deaths

Back to basics

Anxiety and distress in pregnancy and following delivery

Episodes of tearfulness, anxiety and depressive symptoms are commonplace, particularly in first-time mothers. Mostly these will be mild and self-limiting. However, in some these symptoms can be the early signs of a more serious illness (Box 14.5).

Recommendations

Preconception counselling

Maternity services

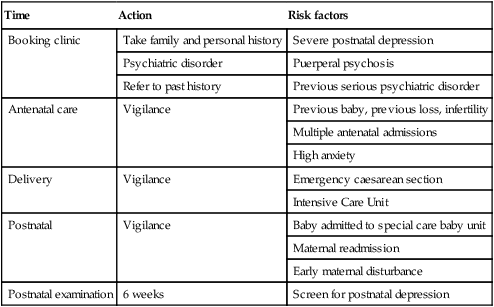

Midwives and obstetricians must ensure that women are asked at early pregnancy assessment about previous psychiatric history. Those with a history of serious illness should be regarded as high risk and management plans put in place (Table 14.1). Postnatal care should be extended to include the period of maximum risk.

Table 14.1

| Time | Action | Risk factors |

| Booking clinic | Take family and personal history | Severe postnatal depression |

| Psychiatric disorder | Puerperal psychosis | |

| Refer to past history | Previous serious psychiatric disorder | |

| Antenatal care | Vigilance | Previous baby, previous loss, infertility |

| Multiple antenatal admissions | ||

| High anxiety | ||

| Delivery | Vigilance | Emergency caesarean section |

| Intensive Care Unit | ||

| Postnatal | Vigilance | Baby admitted to special care baby unit |

| Maternal readmission | ||

| Early maternal disturbance | ||

| Postnatal examination | 6 weeks | Screen for postnatal depression |