CHAPTER 27 Psoas block

Clinical anatomy

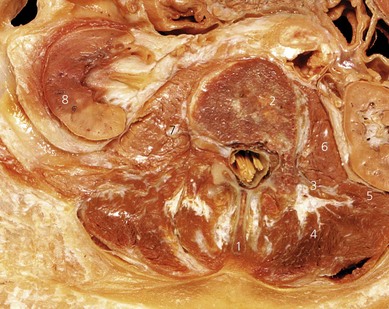

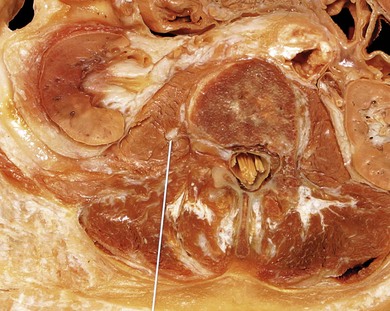

The lumbar plexus is formed by the ventral rami of the first three lumbar nerves and the greater part of the ventral ramus of the fourth, with a contribution from the twelfth thoracic nerve root in 50% of cases. It lies in front of the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae, deep within the psoas major muscle (Fig. 27.1). The nerve roots of the lumbar plexus lie in a ‘cleavable’ space in the psoas major muscle (Fig. 27.2). The space is limited superiorly by the insertion of psoas major on the body of the vertebrae; posteriorly by the lumbar transverse processes and peridural space; and anteriorly by the aponeurotic continuation of the fascia iliaca. The erector spinae (medial) and quadratus lumborum (lateral) muscles are superficial to and posterior to the psoas muscle.

Anatomically, the psoas muscle is regarded as one mass and there is no ‘compartment’ as such within the muscle. Nevertheless, injectate does infiltrate the muscle (Fig. 27.3) and covers the lumbar roots and nerves running within the muscle. The roots join and form the lumbar plexus within the psoas muscle. Branches of the plexus include the femoral, obturator, and lateral cutaneous nerves of the thigh.

Surface anatomy

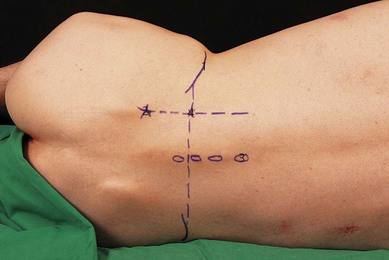

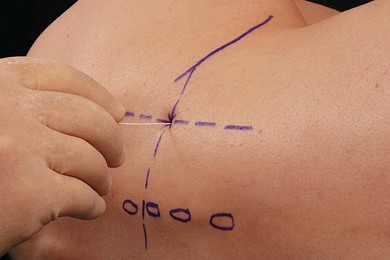

Important landmarks for the psoas block include the iliac crests, the posterior superior iliac spine, and the vertebral column (Fig. 27.4). The posterior superior iliac spine is the bony prominence at the posterior end of the iliac crest. It is directly below the ‘sacral dimple’ (dimple of Venus), a dimple in the skin visible above the buttock, close to the midline.

Sonoanatomy

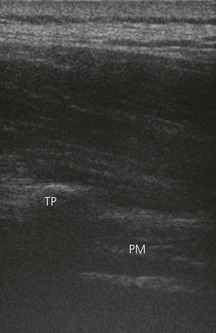

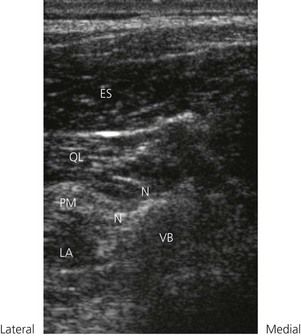

Ultrasonographic visualization of the psoas muscle in adults requires a low frequency transducer (5–8 MHz) due to the depth of the lumbar plexus (5–8 cm). A high frequency transducer can also be used, particularly in children. For longitudinal sonograms, the transducer is placed 3 cm lateral to the spinous processes (Fig. 27.5). This allows for identification of the transverse processes. The transverse processes produce bright hyperechoic signals, with signal loss distally. The psoas muscle is seen deep to these structures (Fig. 27.6). The transducer is advanced caudally and then cranially to identify the respective lumbar interspaces. The sacrum is identified as a continuous hyperechoic line. The longitudinal sonographic pattern of the psoas muscle demonstrates a hypoechoic background interspersed with hyperechoic bands (dots on transverse view) representing fibrous structures within the muscle. Unlike the sonoanatomy in children, visualization of the lumbar plexus in adults is substantially impaired by these structures, and often is impossible to identify. The kidneys are visualized as oval shaped structures usually at the level of L2 or L3, and therefore can be avoided during ultrasound-guided psoas compartment block. The kidneys can also be seen to move with respiration. The more hyperechoic, wedge-shaped, psoas muscle lies medial and deeper to the kidneys. At the interspace of L4–L5, the transducer is rotated 90° into the transverse plane (Fig. 27.7).

Figure 27.7 Orientation of the ultrasound transducer when performing the psoas block in the transverse plane.

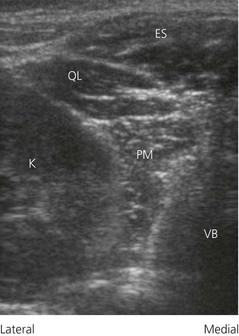

The use of the transverse plane at this level minimizes bony interference. The erector spinae and quadratus lumborum muscles are identified superficial to the articular processes of the vertebral bodies. The psoas muscle is seen deep to the articular process as a hyperechoic structure interspersed with hypoechoic dots or speckles. The signal ‘drop-out’ from the vertebral body of L4 is seen distal to the psoas muscle (Fig. 27.8).

Technique

Landmark-based approach

The lumbar plexus can be blocked with a single injection as it passes through the psoas muscle. As this is a deep block, sedation is indicated for patient comfort and the needle track should be anesthetized with local anesthetic. The patient is placed in the lateral position, with the side to be blocked uppermost and the hips flexed (Fig. 27.9). This block is commonly performed combined with a sciatic nerve block. The two blocks can be performed with the patient in the same position if the classical Labat posterior sciatic approach is used.

Figure 27.9 Patient position for the psoas block. The patient is placed in the lateral position, with both hips flexed.

A 100-mm insulated stimulating needle is used. The stimulating current is set at 1.0 mA, 2 Hz, and 0.1 ms. The needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin (Fig. 27.10), using the needle insertion point as described previously and traverses the following structures: skin, fat, erector spinae, and quadratus lumborum muscles (Fig. 27.11). Contact with the transverse process is an important reference point. The plexus lies 2–3 cm deep to the transverse process, 7–9 cm from the skin. If the transverse process (L4) is contacted, the needle should be redirected below, because passing above increases the risk of renal puncture. Normal kidney extends down to the L3 level.

Figure 27.11 Lumbar (L2) sagittal section illustrating needle orientation and endpoint for the psoas block.

When the needle position is satisfactory, incremental injection of local anesthetic is made, with repeated aspiration for blood and cerebrospinal fluid (40 mL total volume).Intravenous access, electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse oximetry and blood pressure monitoring are established. Maximized comfort for the operator and patient is an important step in pre-procedure preparation. Sedation is required for patient comfort as a result of the depth of the block. For the ultrasound-guided psoas block, the patient is placed in the prone or lateral position, with the side to be blocked uppermost and the hips flexed (Fig. 27.12). A pillow is placed under the abdomen to straighten the lumbar lordosis if the prone position is used. The operator stands or sits on the side to be blocked (Fig. 27.12). For the psoas block, the ultrasound screen is placed at the same level opposite the side to be blocked. The patient may also be placed in the lateral position.

The lumbar region at the L4–L5 is scanned with a 5 MHz curvilinear or 13 MHZ linear transducer in the longitudinal and transverse planes, as described earlier, to image the relevant sonoanatomy. The ultrasound screen should be made to look like the scanning field. That is, the right side of the screen represents the right side of the field. Adjustable ultrasound variables such as scanning mode, depth of field, and gain are optimized. The optimum transverse transducer position is marked. The skin is disinfected with antiseptic solution and draped. A sterile sheath (CIVCO Medical Instruments, Kalona, IA, USA) is applied over the ultrasound transducer with sterile ultrasound gel (Aquasonic, Parker Laboratories, Fairfield, NJ, USA), and placed over the previously marked area that is covered by another layer of sterile gel. A skin wheal of local anesthetic is raised at the medial edge of the ultrasound transducer. The subcutaneous tissues are also infiltrated with local anesthetic. A 22-GA × 120-mm insulated regional block needle (B. Braun Medical, Bethlehem, PA, USA) is inserted perpendicular to the skin in line with the transducer (Fig. 27.13). A 20-mL syringe connected to extension tubing that is flushed to expel any air is attached to the needle.

The needle is then advanced under real-time ultrasound guidance between the transverse processes towards the posterior part of the psoas muscle (Fig 27.14). Close proximity to the lumbar plexus is demonstrated by quadriceps twitches at 0.5 mA. Following negative aspiration for blood or cerebrospinal fluid, 1–2 mL of local anesthetic solution is then injected and traced sonographically. Verification of final needle position, spread of solution within the psoas compartment, or fine adjustments to needle position, can be achieved by imaging in the longitudinal plane.

Adverse effects

Capdevila X, Macaire P, Dodure C, et al. Continuous psoas compartment block for postoperative analgesia after total hip arthroplasty: new landmarks, technical guidelines, and clinical evaluation. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1606-1613.

Chayen D, Nathan H, Chayen M. The psoas compartment block. Anesthesiology. 1976;45:95-99.

Kirchmair L, Enna B, Mitterschiffthaler G, et al. Lumbar plexus in children. A sonographic study and its relevance to pediatric regional anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:445-450.

Kirchmair L, Entner T, Kapral S, Mitterschiffhaler G. Ultrasound guidance for the psoas compartment block: an imaging study. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:706-710.

Mannion S, O’Callaghan S, Walsh M, et al. ‘In with the new, out with the old?’ – comparison of two approaches for psoas compartment block. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:259-264.

Turker G, Uckunkaya N, Yavascaoglu B, et al. Comparison of the catheter-technique psoas compartment block and the epidural block for analgesia in partial hip surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:30-36.