Prune-Belly Syndrome

Frohlich first reported a neonate born with congenital absence of his abdominal musculature in 1839 and Parker later described the accompanying genitourinary tract abnormalities of hydroureteronephrosis, megacystis, and undescended testes (UDT).1,2 Combined, this triad comprises the condition known as ‘prune-belly syndrome’ (PBS), which was coined by Osler in 1901 (Fig. 61-1).3 Eagle and Barrett reviewed this rare, congenital syndrome and detailed the characteristic features that includes congenital absence or deficiency of the abdominal wall musculature, urinary tract abnormalities including a large hypotonic bladder (megacystis), dilated ureters, dilated prostatic urethra, and bilateral UDT.4 In addition, other anomalies, such as cardiac, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, renal and orthopedic can also be present.5 In an effort to quell the negative connotation that may be associated with this terminology, various other labels have been used, including Eagle–Barrett syndrome, triad syndrome, and abdominal musculature deficiency (AMD) syndrome.5–7 Despite the good intentions of the new nomenclature, the most widely accepted designation has remained ‘prune-belly syndrome.’

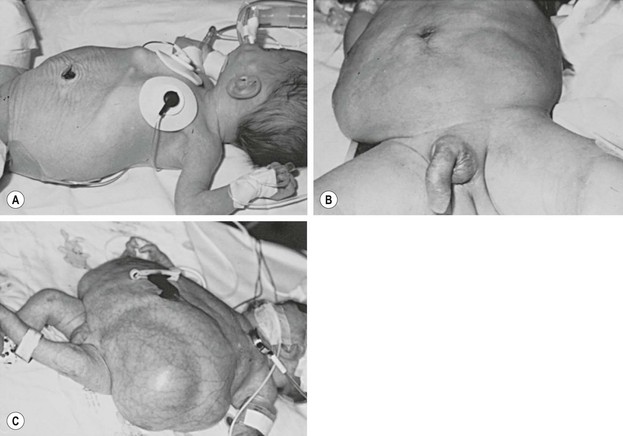

FIGURE 61-1 Variable degrees of abdominal wall laxity can be seen in patients with PBS. (A) Subtle wrinkling in a less severely affected infant. (B) Typical appearance. (C) Severely affected neonate. (Courtesy of D. M. Joseph, MD.)

The incidence of PBS is approximately 3.8 per 100,000 live births based on data from the Kids’ Inpatient Database.8 Of those affected, nearly 50% are white, 30% black, and 10% Hispanic. Children with incomplete forms of the condition may present with the typical abdominal wall changes, but no urologic or testicular manifestations. Using strict criteria for the definition of PBS, which includes cryptorchidism, all patients must be male. Female patients, however, with characteristic abdominal wall and urologic findings, make up a small proportion of patients with an incomplete form of PBS.9,10

Genetics

Genetic factors may play a role, yet no specific gene defect for PBS has been identified. Hepatocyte-nuclear factor-1β (HNF1β), a transcription factor responsible for regulating gene expression necessary for mesodermal and endodermal development, has recently become a gene of interest. Two case reports of PBS with interstitial deletions in chromosome 17q12 encompassing HNF1β have been described.11,12 However, recently, 32 patients with PBS were screened for the presence of HNF1β mutations and only 1 (3%) was found to have a mutation.13

A study evaluating consanguineous union of parents with two male offspring found to have PBS and three with posterior urethral valves point to two loci, 1q and 11p, with likely only one being the causative gene.14 Sporadic cases of PBS have also been associated with other chromosomal abnormalities, including Turner syndrome and trisomies 13 and 18.15–18

Embryology

The etiology for PBS is unclear. While there is no consensus, various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the usual constellation of findings. The most widely accepted mechanism is early urethral obstruction during gestation, leading to a massively distended bladder and ureters.19 This obstruction may be anatomic,20 but others have proposed a functional cause, potentially related to hypoplasia of the prostate.21 Regardless whether if it is functional or anatomic, the urethral obstruction with ensuing bladder distension is thought to lead to the classic abdominal wall muscle and skin changes. In addition, the high grade urethral obstruction and secondary bladder changes can lead to renal dysplasia with oligohydramnios and the subsequent pulmonary dysplasia that is seen in many PBS children. Finally, to account for the cryptorchidism, it is suggested that the distended bladder prevents the normal descent of the testes, thus explaining their intra-abdominal position.

Another reasonable hypothesis involves a primary mesenchymal defect early in embryogenesis that leads to incomplete differentiation or failure of migration of the lateral mesoderm. The failure of migration of the lateral mesoderm explains the typical abdominal wall appearance, but does not account for the genitourinary and testicular abnormalities.22 It is suggested that not only is there a defect in the lateral plate mesoderm, but there is also a defect within the intermediate plate mesoderm, which would then affect embryogenesis of the paramesonephric and mesonephric ducts.23

Clinical Features

Genitourinary Anomalies

Bladder

The bladder is usually very large and irregular with a patent urachus identified in approximately 25% of patients.4 PBS patients typically have a compliant bladder with a very large capacity and smooth wall that has an increased ratio of collagen to muscle fibers. Because of these findings, a delay in the first sensation to void is often seen.24 In some patients with severe muscle loss, the bladder will bulge and give the impression of a pseudodiverticulum most commonly seen at the dome of the bladder.7 The trigone is typically enlarged with displaced ureteral orifices laterally and superiorly, which likely contributes to the high incidence of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).5,7 A poorly defined bladder neck opens into a dilated prostatic urethra. Many patients will void efficiently, but this can vary and some believe a relative outlet resistance exists. Regardless, PBS patients should be followed closely as their ability to empty can deteriorate.25

Ureters

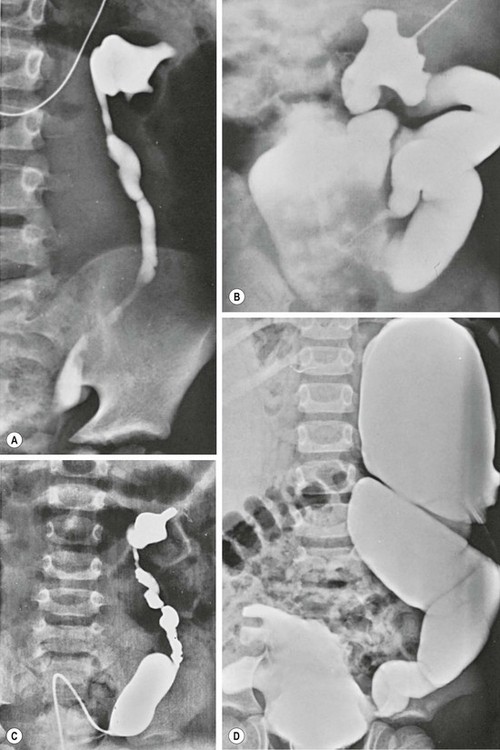

The ureteral orifices are displaced laterally and superiorly, and typically are dilated and tortuous, particularly distally where the smooth muscle is not as normal compared to the proximal ureter (Fig. 61-2). The degree of ureteral pathology can vary and may even be segmental.26 Collagen fibers and connective tissue have been found to be abundant between muscle bundles containing few muscle cells. Thus, there is poor contractility of the ureter and the propulsion of urine is hindered, resulting in upper tract stasis.27,28 With the bladder and ureteral abnormalities, it is no surprise that approximately 75% of patients will have VUR (Fig. 61-3).29 It is rare, however, for PBS patients to have ureteral obstructions.30

FIGURE 61-2 This voiding cystourethrogram in a patient with PBS shows large, dilated distal ureters. The bladder is marked with an asterisk.

FIGURE 61-3 Variable degrees of dilation and dysmorphism of the upper urinary tract are seen in PBS. (A) Dysmorphic renal pelvis with mild ureteral dilation. (B) Calyceal clubbing and a tortuous ‘wandering’ ureter. (C) Dysmorphic pelvis with exaggerated dilation of the distal ureteral spindle. (D) Bizarre appearance of the collecting system as well as the bladder.

Kidneys

Renal abnormalities span a large spectrum ranging from completely normal to severe dysplasia. Of those with dysplasia, one kidney may be affected with a normal contralateral kidney.31 The mechanism for the renal abnormalities is uncertain but possibilities include bladder outlet obstruction and abnormal ureteral bud–metanephric blastema interaction.32

Hydronephrosis is typically seen and can be quite variable in spite of severe ureteral and renal pelvic distension. Most hydronephrosis is nonobstructive in nature, and the degree of hydroureteronephrosis does not directly correlate with the amount of parenchymal injury.30,32

Posterior Urethral, Prostate and Accessory Sex Organs

The extremely dilated posterior urethra seen in PBS children is thought to be secondary to generalized hypoplasia of the prostate epithelium with replacement of the normal smooth muscle anteriorly with connective tissue. While obstructive lesions are rare in the distal posterior urethra,29,33 several investigators have described valve-like obstructive tissue in this location.34–36

The prostate appears widened secondary to the loss of smooth muscle support. One theory supporting this finding is an abnormal epithelial–mesenchymal interaction (Fig. 61-4).20,37 Ejaculatory failure can result from this lack of normal prostatic parenchyma. Some patients may have retrograde ejaculation due to an incompetent bladder neck.34,38

FIGURE 61-4 Posterior urethral dilation (asterisk) is often found in children with PBS. This dilation is similar to that seen in boys with posterior urethral valves.

The vas and seminal vesicles are typically affected, with atresia commonly present. However, some patients present with dilation of both of these structures.23

Anterior Urethra

Typically the anterior urethra is normal. However, atresia of the bulbar or membranous urethra has been reported, occurring in 18% of patients in one review.39

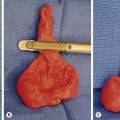

PBS is also associated with two variations of megalourethra.40 The scaphoid megalourethra, the most common and less severe form, is associated with a deficiency of the spongiosum and preservation of the normal glans and corporal bodies (Fig. 61-5). The fusiform type has a deficiency of not only the spongiosum, but also of the corpus cavernosum.41 With voiding, the entire phallus enlarges in patients with the fusiform variety, while those children with the scaphoid form only have dilation of the anterior urethra.

Testes

Most children have bilateral intra-abdominal testes which are commonly found near the ureterovesical junction. More proximal locations have also been described.5,7 Data have varied regarding testicular histology in patients with PBS. Some reports have described normal testicular histology and other series have found diminished spermatogonia with Leydig cell hyperplasia when compared to normal controls, suggesting the testicular findings are caused by more than the cryptorchid state.7,42 Regardless of the histological findings, azospermia is the rule in adult PBS patients, with no reported cases of a natural paternity from patients with PBS.43

Extragenitourinary Anomalies

Abdominal Wall

The most characteristic clinical finding in PBS patients is the wrinkled and floppy appearance to the abdominal wall with bulging flanks and creased skin in the newborn. As patients age and the amount of cutaneous abdominal adipose tissue increases, a more potbelly appearance is noted. The degree of the ‘pruned’ appearance and deficiency of the abdominal wall musculature can vary significantly (see Figure 61-1). While rarely completely absent, the medial and inferior aspects of the abdominal wall are most severely involved, with normal or near-normal abdominal wall at the periphery.30,44 The most affected individual muscle is the transversus abdominis followed in decreasing frequency by the rectus abdominis inferior to the umbilicus, internal oblique, external oblique, and superior aspect of the rectus.29 While the innervation of the abdominal muscle appears unaffected, microscopy has found variations in or decreased muscle fiber size, excessive collagen accumulation, and myofilamentous disarray and loss.45

Cardiac

Cardiac anomalies are present in approximately 10% of affected children. The most common findings include patent ductus arteriosus, atrial and ventricular septal defects, and tetralogy of Fallot.46,47

Pulmonary

Pulmonary issues are common and typically related to the degree of renal dysplasia and oligohydramnios. Neonates exhibiting pulmonary distress should be presumed to have pulmonary hypoplasia and hyaline membrane disease. These children are also at increased risk for both pneumonia and spontaneous pneumothorax which is not necessarily related to the degree of hypoplasia.48 Older patients may be found to have significant restrictive lung disease thought to be related to musculoskeletal abnormalities rather than parenchymal lung disease.49

Gastrointestinal

The most common gastrointestinal anomaly is intestinal malrotation.29 This is thought to be due to an incomplete rotation of the midgut leading to a narrow mesentery.50 Other intestinal abnormalities include persistent cloaca, gastroschisis, omphalocele, imperforate anus, colonic atresia, volvulus, and anorectal malformation.50–53 A similar condition to PBS, known as megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (MMIHS), presents with a functional obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract with malrotation, microcolon, and a large nonobstructed bladder. Some have postulated a common pathogenesis, and a very rare case of both MMIHS and PBS has been reported.54,55 Chronic constipation can be a life-long issue and is believed to be due to lack of intra-abdominal pressure from the lax abdominal wall.

Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal abnormalities are common, occurring in approximately 50% of children.56–58 The most common orthopedic deformity is clubfoot, with an incidence of at least 25%, and nearly 50% are affected bilaterally.58 Other findings include congenital scoliosis, talipes equinovarus, and pectus excavatum.56,58 The specific mechanism leading to the orthopedic issues is unknown, but it is postulated to be secondary to in utero compression and oligohydramnios.59

Clinical Presentation

Antenatal Diagnosis and Management

Patients with PBS present antenatally similarly to those patients with posterior urethral valves or other causes of bladder outlet obstruction. The typical antenatal ultrasound findings include bilateral hydroureteronephrosis, a distended bladder, and an irregular abdominal wall circumference.60 These findings are not specific for PBS, but should be included in the differential diagnosis. The classic findings are typically seen early in the third trimester, but there have been reports of diagnosis as early as 11 weeks.61,62

In utero intervention has been proposed in patients with severe lower urinary tract obstruction meeting certain criteria, including favorable urine biochemistries. One review identified the amniotic fluid volume and renal parenchymal appearance to be the most specific in defining prognosis for early intervention.63 More recently, perinatal survival in 300 fetuses was improved by prenatal bladder drainage in patients with severe bladder obstruction.64 However, even with bladder drainage, there was no guarantee of good postnatal renal function. Fetal interventions, listed in order of increasing complexity, include vesicocentesis, vesico-amniotic shunting, and fetal cystoscopy.65 Each therapeutic option has risks to both the fetus and mother. One case study reported the viable birth of a child with unfavorable prognostic findings after 32 vesicocenteses and amnioinfusion procedures.66 Currently, it is the rare patient with PBS who would be considered a candidate for antenatal therapy as most of these pregnancies are carried to term.67

Neonatal Presentation

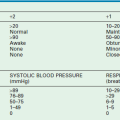

The initial management entails a rapid and complete evaluation of all organ systems. A three-category classification system has been described by Woodward to aid clinicians in regards to the prognosis of children with PBS (Box 61-1).

The pulmonary and cardiac systems, if involved, are the first concern in these children. Initial urologic care includes a physical exam paying particular attention to the abdomen and assessing for kidney and bladder enlargement. Urethral atresia needs to be excluded as prompt intervention is required for bladder obstruction. Initial assessment of renal function is important, but early postnatal creatinine levels are most reflective of the mother. Therefore, electrolyte and creatinine trends are more predictive of long-term function. A nadir creatinine of >0.7 mg/dL in a term infant is a poor prognostic sign noted by several groups.68,69

Once stable, renal and bladder ultrasound is recommended to assess the renal parenchyma and degree of upper and lower tract dilation. Voiding cystourethrography is performed to assess bladder emptying, the bladder outlet, and VUR. Nuclear renography is typically performed at 4–6 weeks of age to assess renal function and obstruction.

Management

A more conservative approach with close surveillance and aggressive medical management means surgical intervention is only needed in those patients with recurrent or persistent infections, or proven obstruction. Some studies have shown that patients can be maintained free of urinary tract infection (UTI), without worsening of their bladder dynamics and renal function, using this approach.70,71 The argument for a more minimalistic approach is based on the fact that surgery has not been shown to slow progression of renal dysfunction, particularly in children with severe renal dysplasia.

The goal of both approaches is to keep the child free of UTI. Acquired renal scarring secondary to pyelonephritis is a common problem in children with PBS.28 Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended in all neonates, regardless of VUR status. Particular attention to urinary stasis, either at the bladder level or more proximally, is important.

Surgical Management

Genitourinary System

Urinary diversion may be a necessary temporary procedure in the setting of bladder outlet obstruction. The Blocksom technique (as modified by Duckett) is the preferred approach with special attention to creating a capacious stoma.72 If a large diverticulum is encountered during creation of the vesicostomy, it should be excised.

An internal urethrotomy may be needed in the older child with increased bladder outlet resistance clinically manifesting as poor bladder emptying and a large postvoid residual. An improvement in urinary flow rates and the overall radiographic appearance, along with lower postvoid residual urine, have been found following urethrotomy.70

Megalourethra is best treated with penile degloving, excision of the redundant urethra, and urethral tailoring and reconstruction. Urethral atresia requires immediate management in the neonatal period with a temporary cutaneous vesicostomy. Achieving a functional urethra usually requires a formal urethroplasty involving complex skin flaps and/or grafts. Progressive dilation of the hypoplastic urethra has been reported as an alternative approach.73

Poor bladder contractility and incomplete emptying is common. A spectrum of approaches can be tried to reduce the bladder size and create a more normal, spherical-shaped bladder including excision of the urachal diverticulum, complex reconstructive operations involving detrusor plication, or the creation of overlapping bladder flaps.74,75 While early postoperative results seemed to be encouraging, long-term results have noted recurrence of a large bladder capacity and poor emptying.74 Currently reduction cystoplasty is performed at the time of ureteral reconstruction and is rarely performed as a primary procedure. Options to improve bladder emptying include clean intermittent catheterization via the urethra or a continent catheterizable channel.

Orchiopexy

The timing of orchiopexy is dependent on the child’s overall health and the need for transscrotal positioning of the UDT at a young age. In the healthy child, bilateral orchiopexy is typically performed via a transabdominal approach around 6 months of age. Those infants requiring other procedures earlier in life can have the orchiopexies performed at the same time. The flaccid abdomen allows for excellent exposure and ligation of the internal spermatic vessels is usually not required for children less than two years of age.76 In older children or those with high intra-abdominal testes, a primary or staged Fowler–Stephens approach may be needed. With the recent advancements in laparoscopy, this approach is promising, particularly in older children and those not requiring other concomitant surgery.77,78 Reports of laparoscopic orchidopexy in PBS patients highlight technical considerations due to the floppy nature of the abdominal wall, including the use of smaller incisions, suture fixation of ports, and higher gas flow rates.79,80

Abdominoplasty

The management of the abdominal wall in children with PBS is determined by the severity of the condition. In children with very mild degrees of deformity, observation is usually preferred with some children having spontaneous improvement in their appearance. In those with more significant degrees of abdominal wall laxity, abdominoplasty is usually recommended as the cosmetic and psychological benefit is believed to outweigh the risks of the operation. Pulmonary, bladder, and bowel function following abdominoplasty may be improved, but is not well substantiated.56,81 The timing of the abdominoplasty is dictated by the child’s general health and need for future reconstructive operations. Children as young as 6 months have undergone abdominal wall reconstruction at the same setting as orchiopexy or bladder reconstruction.

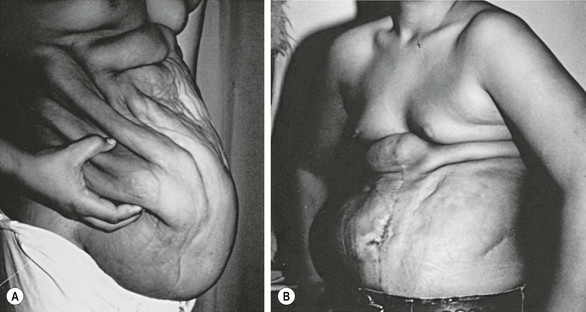

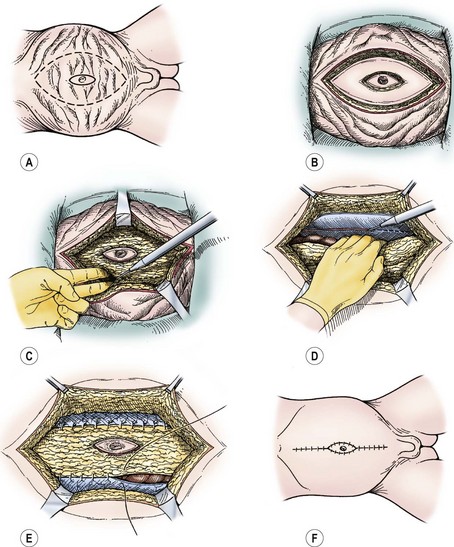

Several methods and modifications have been described for abdominal wall reconstruction. Popular techniques include those described by Monfort82 or Ehrlich.83 The Ehrlich technique utilizes a transabdominal approach through a vertical midline incision with preservation of the umbilicus on a vascular pedicle via the inferior epigastric artery.84 The skin and subcutaneous tissues are then elevated off the underlying fascia and muscle, with a pants over vest buttressing of the more normal lateral fascia and abdominal muscle. The excess abdominal skin is then removed and reapproximated longitudinally in the midline (Fig. 61-6).

FIGURE 61-6 The Ehrlich technique was used in this patient. (A) The preoperative appearance of the abdominal wall; (B) the postoperative view.

Monfort’s technique also employs a vertical incision. However, his modification uses an elliptically oriented incision as a means of excising the redundant skin. The incision usually extends from the tip of the xyphoid down to the pubis. A second elliptical incision is then made around the umbilicus for its preservation. Similar to the Ehrlich technique, the skin is dissected off the fascia and muscle laterally, at least to the anterior axillary line. However, the Monfort procedure includes the use of vertical relaxing fascial incisions lateral to the superior epigastric arteries, allowing mobilization of the lateral fascial flaps over a central fascial bridge. Durable functional results have been reported with this approach as well (Fig. 61-7).82,85

FIGURE 61-7 The Monfort abdominoplasty is depicted. (A) Skin incisions circumscribe the umbilicus and define areas of adjacent abdominal wall redundancy to be removed. (B) Excision of skin (epidermis and dermis alone) by using electrocautery. (C) Abdominal wall central plate is incised at the lateral borders of the rectus muscle on either side, creating a central musculofascial plate. (D) The parietal peritoneum overlying the lateral abdominal wall musculature is scored with electrocautery. (E) Edges of the central plate are sutured along the scored line. (F) Excess skin is removed, and the midline approximation envelops the previously isolated umbilicus.

Others have described alternative techniques for abdominal wall reconstruction which include extraperitoneal dissection, fascial folding, or laparoscopic-assisted approaches.86–88 Ehrlich et al. recently reported their long-term results with a mean follow-up of 20.4 years and found no major complications and satisfaction with the cosmetic appearance.89

Renal Transplant

Close follow-up and monitoring of renal function is essential in patients with PBS. Approximately 30% of patients presenting with renal insufficiency will develop chronic renal failure during childhood or in their adolescent years.90,91 The timing of lower urinary tract reconstruction and renal transplantation has been debated. Some advocate urinary reconstruction prior to renal transplantation so that the immunosuppressive therapy does not impair healing.92

References

1. Frohlich, F. Der Mangel der Muskein, insbesondere der Seitenbauchmuskein. Wurzburg: CA Surn; 1839.

2. Parker, R. Absence of abdominal muscles in an infant. Lancet. 1894; 1:1252.

3. Osler, W. Congenital absence of the abdominal muscles with distended and hypertrophied urinary bladder. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1901; 12:331.

4. Eagle, J, Barrett, G. Congenital deficiency of abdominal musculature with associated genitourinary abnormalities: A syndrome: Report of nine cases. Pediatrics. 1950; 6:721–736.

5. Williams, DI, Burkholder, GV. The prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1967; 98:244–251.

6. Welch, KJ, Kraney, GP. Abdominal musculature deficiency syndrome prune-belly. J Urol. 1974; 111:693–700.

7. Nunn, IN, Stephens, FD. The triad syndrome: A composite anomaly of the abdominal wall, urinary system and testes. J Urol. 1961; 86:782–794.

8. Routh, JC, Huang, L, Retik, AB, et al. Contemporary epidemiology and characterization of newborn males with prune-belly syndrome. Urology. 2010; 76:44.

9. Austin, JC, Canning, DA, Johnson, MP, et al. Vesicoamniotic shunt in a female fetus with the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 2001; 166:2382.

10. Reinberg, Y, Shapiro, E, Manivel, JC, et al. Prune-belly syndrome in females: A triad of abdominal musculature deficiency and anomalies of the urinary and genital systems. J Pediatr. 1991; 118:395–398.

11. Murray, PJ, Thomas, K, Mulgrew, CJ, et al. Whole gene deletion of the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1b gene in a patient with the prune-belly syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008; 23:2414–2415.

12. Haeri, S, Devers, PL, Kaiser-Rogers, KA, et al. Deletion of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1-beta in an infant with prune-belly syndrome. Am J Perinatol. 2010; 2(7):559–563.

13. Granberg, CF, Harrison, SM, Dajusta, D, et al. Genetic basis of prune-belly syndrome: Screening for HNF1β gene. J Urol. 2012; 187:272–278.

14. Weber, S, Mir, S, Schlingmann, KP, et al. Gene locus ambiguity in posterior urethral valves/prune-belly syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005; 20:1036–1042.

15. Lubinsky, M, Koyle, K, Trunca, C. The association of ‘prune-belly’ with Turner’s syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1980; 134:1171–1172.

16. Beckmann, H, Rehder, H, Rauskolb, R. Prune-belly sequence associated with trisomy 13. Am J Med Genet. 1984; 19:603–604.

17. Frydman, M, Magenis, RE, Mohandas, TK, et al. Chromosome abnormalities in infants with prune-belly anomaly: Association with trisomy 18. Am J Med Genet. 1983; 15:145–148.

18. Kupferman, JC, Druschel, CM, Kupchik, GS. Increased prevalence of renal and urinary tract anomalies in children with Down syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009; 124:e615–e621.

19. Popek, EJ, Tyson, RW, Miller, GJ, et al. Prostate development in prune-belly syndrome (PBS) and posterior urethral valves (PUV): Etiology of PBS–lower urinary tract obstruction or primary mesenchymal defect? Pediatr Pathol. 1991; 11:1–29.

20. Pagon, RA, Smith, DW, Shepard, TH. Urethral obstruction malformation complex: A cause of abdominal muscle deficiency and the ‘prune-belly’. J Pediatr. 1979; 94:900–906.

21. Moerman, P, Fryns, JP, Goddeeris, P, et al. Pathogenesis of the prune-belly syndrome: A functional urethral obstruction caused by prostatic hypoplasia. Pediatrics. 1984; 73:470–475.

22. Straub, E, Spranger, J. Etiology and pathogenesis of the prune-belly syndrome. Kidney Int. 1981; 20:695–699.

23. Stephens, FD, Gupta, D. Pathogenesis of the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1994; 152:2328–2331.

24. Workman, SJ, Kogan, BA. Fetal bladder histology in posterior urethral valves and the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1990; 144:337–339.

25. Kinahan, TJ, Churchill, BM, McLorie, GA, et al. The efficiency of bladder emptying in the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1992; 148:600–603.

26. Ehrlich, RM, Brown, WJ. Ultrastructural anatomic observations of the ureter in the prune-belly syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1977; 13:101–103.

27. Gearhart, JP, Lee, BR, Partin, AW, et al. A quantitative histological evaluation of the dilated ureter of childhood. II: Ectopia, posterior urethral valves and the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1995; 153:172–176.

28. Woodard, JR, Zucker, I. Current management of the dilated urinary tract in prune-belly syndrome. Urol Clin North Am. 1990; 17:407–418.

29. Berdon, WE, Baker, DH, Wigger, HJ, et al. The radiologic and pathologic spectrum of the prune-belly syndrome. The importance of urethral obstruction in prognosis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1977; 15:83–92.

30. Manivel, JC, Pettinato, G, Reinbert, Y, et al. Prune-belly syndrome: Clinicopathologic study of 29 cases. Pediatr Pathol. 1989; 9:691–711.

31. Schwarz, RD, Stephens, FD, Cussen, LJ. The pathogenesis of renal dysplasia. I. Quantification of hypoplasia and dysplasia. Invest Urol. 1981; 19:94–96.

32. Woodard, JR, Parrott, TS. Reconstruction of the urinary tract in prune-belly uropathy. J Urol. 1978; 119:824–828.

33. Hoagland, MH, Hutchins, GM. Obstructive lesions of the lower urinary tract in the prune-belly syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987; 111:154–156.

34. Volmar, KE, Fritsch, MK, Perlman, EJ, et al. Patterns of congenital lower urinary tract obstructive uropathy: Relation to abnormal prostate and bladder development and the prune-belly syndrome. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2001; 4:467–472.

35. Nouaili, EB, Chaouachi, S, Nouira, F, et al. Concordant posterior urethral valves in male monochorionic twins with secondary prune-belly syndrome. Tunis Med. 2008; 86:1086–1088.

36. Weber, S, Mir, S, Schlingmann, KP, et al. Gene locus ambiguity in posterior urethral valves/prune-belly syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005; 20:1036–1042.

37. Deklerk, DP, Scott, WW. Prostatic maldevelopment in the prune-belly syndrome: A defect in prostatic stromal-epithelial interaction. J Urol. 1978; 120:341–344.

38. Woodhouse, CR, Snyder, HM, 3rd. Testicular and sexual function in adults with prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1985; 133:607–609.

39. Reinberg, Y, Chelimsky, G, Gonzalez, R. Urethral atresia and the prune-belly syndrome. Report of 6 cases. Br J Urol. 1993; 72:112–114.

40. Shrom, SH, Cromie, WJ, Duckett, JW, Jr. Megalourethra. Urology. 1981; 17:152–156.

41. Mortensen, PH, Johnson, HW, Coleman, GU, et al. Megalourethra. J Urol. 1985; 134:358–361.

42. Orvis, BR, Bottles, K, Kogan, BA. Testicular histology in fetuses with the prune-belly syndrome and posterior urethral valves. J Urol. 1988; 139:335–337.

43. Kolettis, PN, Ross, JH, Kay, R, et al. Sperm retrieval and intracytoplasmic sperm injection in patients with prune-belly syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1999; 72:948–949.

44. Mininberg, DT, Montoya, F, Okada, K, et al. Subcellular muscle studies in the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1973; 109:524–526.

45. Afifi, AK, Rebeiz, J, Mire, J, et al. The myopathology of the Prune-belly syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 1972; 15:153–165.

46. Adebonojo, FO. Dysplasia of the anterior abdominal musculature with multiple congenital anomalies. Prune-belly or triad syndrome. J Natl Med Assoc. 1973; 65:327–333.

47. Yoshida, M, Matsumura, M, Shintaku, Y, et al. Prenatally diagnosed female prune-belly syndrome associated with tetralogy of Fallot. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1995; 39:141–144.

48. Geary, DJ, MacLusky, IB, Churchill, BM. A broader spectrum of abnormalities in the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1986; 135:324–326.

49. Crompton, CH, MacLusky, IB, Geary, DF. Respiratory function in the prune-belly syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1993; 68:505–506.

50. Wright, JR, Jr., Barth, RF, Neff, JC, et al. Gastrointestinal malformations associated with prune-belly syndrome: Three cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Pathol. 1986; 5:421–448.

51. Morgan, CL, Jr., Grossman, H, Novak, R. Imperforate anus and colon calcification in association with the prune-belly syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1978; 7:19–21.

52. Mahajan, JK, Ojha, S, Rao, KL. Prune-belly syndrome with anorectal malformation. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 14:351–354.

53. Giuliani, S, Vendryes, C, Malhotra, A, et al. Prune-belly syndrome associated with cloacal anomaly, patent urachal remnant, and omphalocele in a female infant. J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:e39–e42.

54. Oliveira, G, Boechat, MI, Ferreira, MA. Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome in a newborn girl whose brother had prune-belly syndrome: Common pathogenesis? Pediatr Radiol. 1983; 13:294–296.

55. Levin, TL, Soghier, L, Blitman, NM, et al. Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis and prune-belly: Overlapping syndromes. Pediatr Radiol. 2004; 34:995–998.

56. Woodard, JR. Lessons learned in 3 decades of managing the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1998; 159:1680.

57. Brinker, MR, Palutsis, RS, Sarwark, JF. The orthopaedic manifestations of prune-belly (Eagle-Barrett) syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995; 77:251–257.

58. Loder, RT, Guiboux, JP, Bloom, DA, et al. Musculoskeletal aspects of prune-belly syndrome. Description and pathogenesis. Am J Dis Child. 1992; 146:1224–1229.

59. Green, NE, Lowery, ER, Thomas, R. Orthopaedic aspects of prune-belly syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993; 13:496–501.

60. Shih, WJ, Greenbaum, LD, Baro, C. In utero sonogram in prune-belly syndrome. Urology. 1982; 20:102–105.

61. Yamamoto, H, Nishikawa, S, Hayashi, T, et al. Antenatal diagnosis of prune-belly syndrome at 11 weeks of gestation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2001; 27:37–40.

62. Shimizu, T, Ihara, Y, Yomura, W, et al. Antenatal diagnosis of prune-belly syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1992; 251:211–214.

63. Morris, RK, Malin, GL, Khan, KS, et al. Antenatal ultrasound to predict postnatal renal function in congenital lower urinary tract obstruction: Systematic review of test accuracy. BJOG. 2009; 116:1290–1299.

64. Morris, RK, Malin, GL, Khan, KS, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of antenatal intervention for the treatment of congenital lower urinary tract obstruction. BJOG. 2010; 117:382–390.

65. Ruano, R. Fetal surgery for severe lower urinary tract obstruction. Prenat Diagn. 2011; 31:667–674.

66. Galati, V, Beeson, JH, Confer, SD, et al. A favorable outcome following 32 vesicocentesis and amnioinfusion procedures in a fetus with severe prune-belly syndrome. J Pediatr Urol. 2008; 4:170–172.

67. Freedman, AL, Bukowski, TP, Smith, CA, et al. Fetal therapy for obstructive uropathy: Diagnosis specific outcomes. J Urol. 1996; 156:20–723.

68. Noh, PH, Cooper, CS, Winkler, AC, et al. Prognostic factors for long-term renal function in boys with the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1999; 162:1399–1401.

69. Reinberg, Y, Manivel, JC, Pettinato, G, et al. Development of renal failure in children with the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1991; 145:1017–1019.

70. Woodhouse, CR, Kellett, MJ, Williams, DI. Minimal surgical interference in the prune-belly syndrome. Br J Urol. 1979; 51:475–480.

71. Texter, JH, Jr., Koontz, WW, Jr. Dilation of the urethra in males. J Fam Pract. 1980; 11:111–117.

72. Duckett, JW, Jr. Cutaneous vesicostomy in childhood. The Blocksom technique. Urol Clin North Am. 1974; 1:485–495.

73. Passerini-Glazel, G, Araguna, F, Chiozza, L, et al. The P.A.D.U.A. (progressive augmentation by dilating the urethra anterior) procedure for the treatment of severe urethral hypoplasia. J Urol. 1988; 140:1247–1249.

74. Bukowski, TP, Perlmutter, AD. Reduction cystoplasty in the prune-belly syndrome: A long-term followup. J Urol. 1994; 152:2113–2116.

75. Perlmutter, AD. Reduction cystoplasty in prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1976; 116:356–362.

76. Fallat, ME, Skoog, SJ, Belman, AB, et al. The prune-belly syndrome: A comprehensive approach to management. J Urol. 1989; 142:802–805.

77. Docimo, SG, Moore, RG, Adams, J, et al. Laparoscopic orchiopexy for the high palpable undescended testis: Preliminary experience. J Urol. 1995; 154:1513–1515.

78. Patil, KK, Duffy, PG, Woodhouse, CR, et al. Long-term outcome of Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy in boys with prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 2004; 171:1666–1669.

79. Philip, J, Mullassery, D, Craigie, RJ, et al. Laparoscopic orchidopexy in boys with prune-belly syndrome—outcome and technical considerations. J Endourol. 2011; 25:1115–1117.

80. Saxena, AK, Brinkmann, OA. Unique features of prune-belly syndrome in laparoscopic surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2007; 205:217–221.

81. Smith, CA, Smith, EA, Parrott, TS, et al. Voiding function in patients with the prune-belly syndrome after Monfort abdominoplasty. J Urol. 1998; 159:1675–1679.

82. Monfort, G, Guys, JM, Bocciardi, A, et al. A novel technique for reconstruction of the abdominal wall in the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1991; 146:639–640.

83. Ehrlich, RM, Lesavoy, MA, Fine, RN. Total abdominal wall reconstruction in the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1986; 136:282–285.

84. Ehrlich, RM, Lesavoy, MA. Umbilicus preservation with total abdominal wall reconstruction in prune-belly syndrome. Urology. 1993; 41:231–232.

85. Parrott, TS, Woodard, JR. The Monfort operation for abdominal wall reconstruction in the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1992; 148:688–690.

86. Furness, PD, 3rd., Cheng, EY, Franco, I, et al. The prune-belly syndrome: A new and simplified technique of abdominal wall reconstruction. J Urol. 1998; 160:1195–1197.

87. Franco, I. Laparoscopic assisted modification of the firlit abdominal wall plication. J Urol. 2005; 174:280–283.

88. Levine, E, Taub, PJ, Franco, I. Laparoscopic assisted abdominal wall reconstruction in prune-belly syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. 2007; 58:162–165.

89. Lesavoy, MA, Chang, EI, Suliman, A, et al. Long-term follow-up of total abdominal wall reconstruction for prune-belly syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012; 129:104e–109e.

90. Fontaine, E, Salomon, L, Gagnadoux, MF, et al. Long-term results of renal transplantation in children with the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1997; 158:892–894.

91. Reinberg, Y, Manivel, JC, Fryd, D, et al. The outcome of renal transplantation in children with the prune-belly syndrome. J Urol. 1989; 142:1541–1542.

92. Djakovic, N, Wagener, N, Adams, J, et al. Intestinal reconstruction of the lower urinary tract as a prerequisite for renal transplantation. BJU Int. 2009; 103:1555–1560.