Chapter 36 PROTEINURIA

Key Historical Features

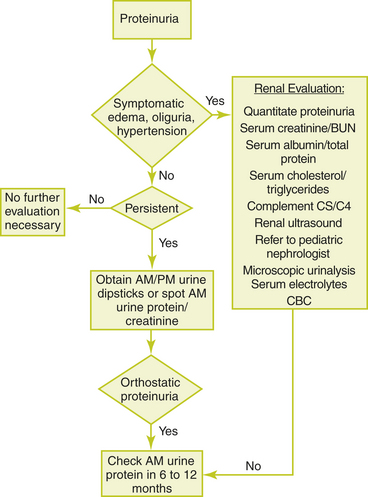

Suggested Work-up

| Repeat urine dipstick two or three additional times | To determine whether proteinuria is persistent |

| Perform urine dipstick on a morning urine sample and a sample later in the day | To determine whether orthostatic proteinuria is the cause |

| Microscopic urinalysis | To evaluate the urinary sediment for hematuria, bacteria, casts, or eosinophils |

| Serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine | To evaluate renal function |

| Serum electrolytes | To evaluate for electrolyte disturbances |

| Serum albumin and total protein | Serum albumin is decreased in nephrotic syndrome |

| Complete blood count (CBC) | To evaluate for infection. Anemia may indicate chronic renal disease. |

| Serum cholesterol and triglycerides | Cholesterol is increased in nephrotic syndrome |

| Complement C3 and C4 levels | Levels are decreased in the glomerulonephritides |

| Renal ultrasound | To help detect anatomic or congenital abnormalities, especially in children under 6 years of age |

Additional Work-up

| Antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer and/or streptozyme test | If postinfectious glomerulonephritis is suspected by history. Referral to a pediatric endocrinologist is recommended for most cases of postinfectious glomerulonephritis. |

| Antinuclear antibody (ANA) | If systemic lupus erythematosus is suspected |

| Hepatitis B and C serologies | If hepatitis B or C infections are suspected |

| HIV testing | If HIV infection is suspected |

| Voiding cystourethrogram | May be indicated if there is a history of recurrent UTIs or if a renal ultrasound reveals scarring |

| Renal biopsy | May be indicated when laboratory tests are abnormal and a glomerular disease is suspected |

| Referral to a pediatric nephrologist | See text for some indications. Generally indicated if renal biopsy is needed, if the patient has hematuria with symptoms of renal disease, if nephrotic-range proteinuria is diagnosed, or if the diagnosis is unclear. |

1. Hogg R.J., et al. National Kidney Foundation’s kidney disease outcomes initiative clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease in children and adolescents: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1416–1421.

2. Hogg R.J. Adolescents with proteinuria and/or the nephrotic syndrome. Adolesc Med Clin. 2005;16:163–172.

3. Loghman-Adham M. Evaluating proteinuria in children. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:1145–1152.

4. Mahan J.D., Turman M.A., Mentser M.I. Evaluation of hematuria, proteinuria, and hypertension in adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44:1573–1589.

5. Patel H.P. The abnormal urinalysis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:325–337.