CHAPTER 28 Protein-Losing Gastroenteropathy

Drs. Karen Kim and Thomas Brasitus contributed to previous versions of this chapter.

DEFINITION AND NORMAL PHYSIOLOGY

In 1947, Maimon and colleagues postulated that fluid emanating from the large gastric folds in patients with Ménétrier’s disease was rich in protein. In 1949, Albright and colleagues discovered, using intravenous infusions of albumin, that hypoproteinemia resulted from excessive catabolism of albumin rather than decreased albumin synthesis.1 By 1956, Kimbel and colleagues demonstrated an increase in gastric albumin production in patients with chronic gastritis; a year later, Citrin and colleagues2 were able to show that the GI tract was the actual site of excess protein loss in patients with Ménétrier’s disease. They showed that the excess loss of intravenously administered radioiodinated albumin could be explained by the appearance of labeled protein in the gastric secretions of such patients.

Subsequent research using 131I-labeled polyvinylpyrrolidone, 51Cr-labeled albumin, and other radiolabeled proteins, as well as immunologic methods measuring enteric loss of α1-antitrypsin (α1-AT), has further characterized the role of the GI tract in the metabolism of serum proteins. In fact, GI tract loss of albumin normally accounts for only 2% to 15% of the total body degradation of albumin, but in patients with severe protein-losing GI disorders, this enteric protein loss may extend to up to 60% of the total albumin pool.3–5

Under physiologic conditions, most endogenous proteins found in the lumen of the GI tract are derived from sloughed enterocytes and from pancreatic and biliary secretions.6 Studies of serum protein loss into the GI tract measured by various methods (e.g., 67Cu-ceruloplasmin, 51Cr-albumin, or α1-AT clearance) have shown that daily enteric loss of serum proteins accounts for less than 1% to 2% of the serum protein pool in healthy individuals, with enteric loss of albumin accounting for less than 10% of total albumin catabolism. In normal subjects, the total albumin pool is approximately 3.9 g/kg in women and 4.7 g/kg in men, with a half-life of 15 to 33 days and a rate of hepatic albumin synthesis of 0.15 g/kg/day, equaling the rate of albumin degradation.7 Excess proteins that enter the GI tract are metabolized by existing proteases much like other peptides, broken down to constituent amino acids, and then reabsorbed. In healthy individuals, GI losses play only a minor role in total protein metabolism, and serum protein levels reflect the balance between protein synthesis and metabolism. However, this balance can be altered markedly in patients with protein-losing gastroenteropathy.8

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Excessive plasma protein loss across the GI epithelium can result from several pathologic alterations of healthy mucosa. Mucosal injury can result in increased permeability to plasma proteins; mucosal erosions and ulcerations can result in the loss of an inflammatory, protein-rich exudate; and lymphatic obstruction or increased lymphatic hydrostatic pressure can result in direct leakage of lymph, which contains plasma proteins. Changes in vascular permeability can affect the concentration of serum proteins in the interstitial fluid, thereby influencing the amount of enteric mucosal protein loss.9 Hypoproteinemia seen in GI disorders can therefore be classified into three groups: (1) increased mucosal permeability to proteins as a result of cell damage or cell loss; (2) mucosal erosions or ulcerations; and (3) lymphatic obstruction.

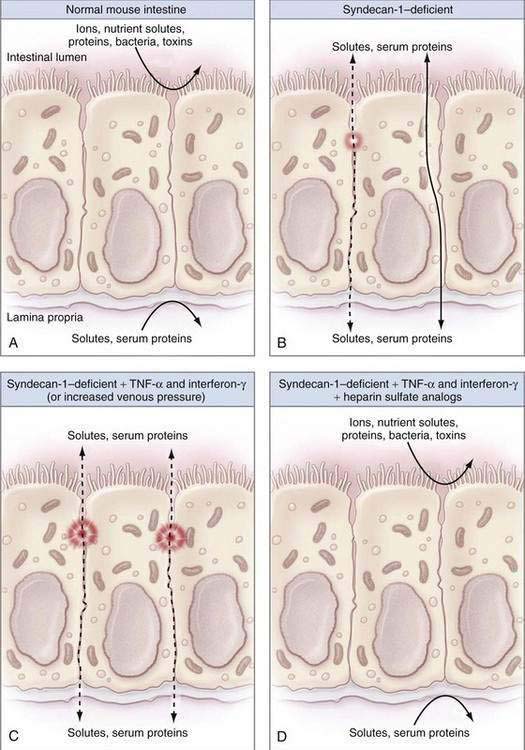

Examining the pathogenesis of protein-losing gastroenteropathy, Bode and colleagues have suggested that the condition might be related to loss of heparan sulfate proteins that are normally present on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells.10,11 Heparan sulfate proteoglycans appear to affect the intestinal barrier by having large extracellular domains that bind to the plasma membrane, known as syndecans, or are attached to a membrane glycolipid, called a glypican.12 These syndecans are important in the maintenance of tight intercellular junctions (see Chapters 2 and 96).

A myriad of diseases are associated with protein-losing gastroenteropathy. These are listed in Table 28-1 and discussed in more detail elsewhere in this text.13–63

Table 28-1 Disorders Associated with Protein-Losing Gastroenteropathy

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Mice that were genetically altered to lack syndecans or other heparan sulfate proteins have alterations to the normal tight intercellular barrier, and leak protein via paracellular pathways into the intestinal lumen (Fig. 28-1). Moreover, treatment of such mice with proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) or interferon-γ leads to significantly defective intercellular junctions and even greater protein loss into the intestine.10 The combination of a syndecan-deficient state and exposure to proinflammatory cytokines leads to even greater albumin flux and protein loss. Finally, reintroduction of heparin sulfate or other syndecans abolishes the protein loss into the lumen of the bowel.

Figure 28-1. Diagrams illustrating the factors that contribute to intestinal integrity in the mouse. A, The normal mouse intestine makes an effective barrier against free diffusion of certain ions, nutrient solutes, proteins, bacteria, and toxins to separate the intestinal lumen (outside) from the lamina propria (inside) effectively. B, As noted by Bode and colleagues,10 syndecan-1–deficient mice have decreased intestinal barrier function as a result of defective intercellular junctions and increased paracellular leaks (dashed line) or increased transcellular protein transport (solid line). C, Syndecan-1–deficient mice that were treated with inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ or surgically to increase their portal venous pressure have massively defective intercellular junctions and large intercellular protein leaks (dashed lines), consistent with protein-losing enteropathy. D, Infusions of heparin sulfate analogs completely reverse the intestinal barrier dysfunction seen in syndecan-1–deficient mice treated with inflammatory cytokines. See text for more details.

(From Lencer WI. Patching a leaky intestine. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:526-8, with permission.)

The loss of serum proteins in patients with protein-losing gastroenteropathy is independent of their molecular weight, and therefore the fraction of the intravascular pool degraded daily remains the same for various proteins, including albumin, immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA, IgM, and ceruloplasmin.8 In contrast, patients with nephrotic syndrome preferentially lose low molecular weight proteins such as albumin. As proteins cross into the GI tract, synthesis of new proteins occurs in a compensatory fashion. Proteins that enter the GI tract are metabolized into constituent amino acids by gastric, pancreatic, and small intestinal enzymes, reabsorbed by specific transporters, and recirculated. When the rate of gastric or enteric protein loss, or both, exceeds the body’s capacity to synthesize new protein, hypoproteinemia develops.6 Hypoalbuminemia, for example, is common in protein-losing gastroenteropathy and results when there is an imbalance between hepatic albumin synthesis, which is limited and can increase only by 25%, and albumin loss, with reductions in the total body albumin pool and albumin half-life.9

Adaptive changes in endogenous protein catabolism may compensate for excessive enteric protein loss, resulting in unequal loss of specific proteins. For example, proteins such as insulin, clotting factors, and IgE have rapid catabolic turnover rates (short half-lives) and, as such, are relatively unaffected by GI losses, because rapid synthesis of these proteins ensues. On the other hand, proteins such as albumin and most gamma globulins, except IgE, are limited in their ability to respond to GI losses, so protein loss from the gut will be manifested by hypoproteinemia (hypoalbuminemia and hypoglobulinemia).8 Other factors also can contribute to the excessive enteric protein loss seen in various diseases. These include impaired hepatic protein synthesis and increased endogenous degradation of plasma proteins.

In addition to hypoproteinemia, protein-losing gastroenteropathy can result in reduced concentrations of other serum components, such as lipids, iron, and trace metals.8 Lymphatic obstruction can result in lymphocytopenia, with resultant alterations in cellular immunity.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Hypoproteinemia and edema are the principal clinical manifestations of protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Most other clinical features reflect the underlying disease process and, as such, the clinical presentation of patients with protein-losing gastroenteropathy is varied (Table 28-2). Hypoproteinemia, the most common clinical sequela, is manifested by a decrease in serum levels of albumin, gamma globulins (IgG, IgA, and IgM, but not IgE), fibrinogen, lipoproteins, α1-AT, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin.8 Levels of rapid turnover proteins, such as retinal binding protein and prealbumin, are typically preserved, despite hypoproteinemia.64 Dependent edema is frequently a clinically significant issue, and results from diminished plasma oncotic pressure. Anasarca is rare in protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Unilateral edema, upper extremity edema, facial edema and macular edema (with reversible blindness), and bilateral retinal detachments have been seen as a consequence of intestinal lymphangiectasia.65 Despite a decrease in serum gamma globulin levels, increased susceptibility to infections is uncommon. Although clotting factors may be lost into the GI tract, coagulation status typically remains unaffected. Circulating levels of proteins that bind hormones, such as cortisol and thyroid-binding proteins, may be substantially decreased, but levels of circulating free hormones are not significantly altered.

Table 28-2 Clinical Manifestations of Protein-Losing Gastroenteropathy

Ig, immunoglobulin.

Most of the clinical findings in patients with protein-losing diseases are the result of the underlying disease state and are not cased by the protein loss itself. For example, small bowel disorders with protein loss as a feature, such as celiac disease or tropical sprue, may be associated with malabsorption and resultant diarrhea, fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, and anemia. Lymphatic obstruction, as occurs with lymphangiectasia, may be seen as lymphocytopenia or abnormal cellular immunity.66

DISEASES ASSOCIATED WITH PROTEIN-LOSING GASTROENTEROPATHY

Diseases associated with protein-losing gastroenteropathy can be divided into three broad categories: (1) diseases without GI mucosal erosions or ulcerations; (2) diseases with GI mucosal erosions or ulcerations; and (3) diseases leading to elevated lymphatic and interstitial pressure (see Table 28-1). More than one of these mechanisms may be operative in some disease states, as is the situation for some infectious diseases.

DISEASES WITHOUT MUCOSAL EROSIONS OR ULCERATIONS

Diseases that damage the GI epithelium without causing erosions or ulcers may lead to surface epithelial cell shedding, resulting in excess protein loss. Lesions of the small intestine that cause malabsorption are often associated with enteric leakage of plasma proteins. Protein loss also may be caused by alterations in vascular permeability caused by vascular injury, such as in lupus vasculitis, IgE-mediated inflammation from an allergic response, infection (parasitic, viral, bacterial overgrowth), increased intercellular permeability, or increased capillary permeability.24–30

Ménétrier’s Disease

Giant hypertrophic gastropathy (Ménétrier’s disease; see Chapter 51) is the most common gastric lesion causing severe protein loss.21,22 Patients usually have dyspepsia, postprandial nausea, emesis, edema, and weight loss and are found to have hypoproteinemia. Prominent and thick gastric folds with substantial mucus and protein-rich exudates are seen; normal gastric glands are replaced by mucus-secreting cells, reducing the number of parietal cells and resulting in hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria. An increase in intercellular permeability results in protein loss. In this disorder, tight junctions between cells are wider than those found in healthy subjects, and it is believed that proteins traverse the gastric mucosa through these widened spaces. Histamine (H2) receptor antagonists, anticholinergic agents, and octreotide may be used to improve symptoms, but patients with persistent abdominal pain or severe unrelenting protein loss require subtotal or total gastrectomy. A possible causal relationship appears to exist between Helicobacter pylori infection and Ménétrier’s disease with protein-losing gastroenteropathy, because resolution of the hypoproteinemia and return of the gastric folds to their normal configuration may occur with eradication of the organism.41–43

Helicobacter pylori Gastritis

H. pylori gastritis in the absence of Ménétrier’s disease (see Chapter 50) has been associated with protein-losing gastropathy and responds to eradication of H. pylori infection.41–43 Some of these patients may have gastric erosions through which protein may be lost.

Allergic Gastroenteropathy

Although allergic gastroenteropathy (see Chapters 9 and 27) is often considered a disease of childhood, it may be seen in adults as well. This syndrome is manifest by symptoms including abdominal pain, vomiting, and sporadic diarrhea; findings include hypoproteinemia, iron deficiency anemia, and peripheral eosinophilia. Serum levels of total protein and albumin, as well as IgA and IgG, will be markedly reduced, whereas levels of IgM and transferrin will be only moderately diminished. Characteristic histology of the small bowel in patients with this disorder includes a marked increase in the number of eosinophils in the lamina propria, and Charcot-Leyden crystals may be found on stool examination.15

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

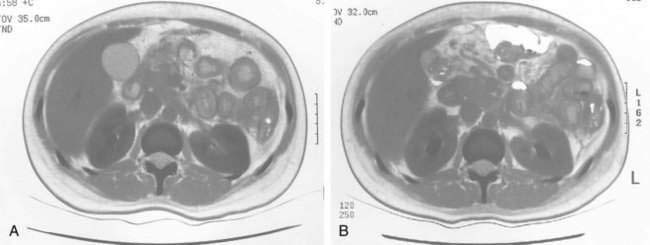

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease not infrequently associated with protein-losing gastroenteropathy (Fig. 28-2).29,30 Mesenteric vasculitis can result in intestinal ischemia, edema, and altered intestinal vascular permeability. In addition, gastritis and mucosal ulcerations, both of which may contribute to excess protein loss, can develop in patients with SLE. Protein-losing gastroenteropathy may be the initial clinical presentation of SLE. Therapy with systemic glucocorticoids, as well as other immunomodulatory agents such as azathioprine and cyclophosphamide, can lead to remission with resolution of clinical symptoms, including protein-losing gastroenteropathy.29,30

DISEASES WITH MUCOSAL EROSIONS OR ULCERATIONS

Mucosal erosions or ulcerations resulting in protein-losing gastroenteropathy can be localized or diffuse and can be caused by benign or malignant disease (see Table 28-1). The severity of protein loss depends on the degree of cellular loss and the associated inflammation and lymphatic obstruction. Diffuse ulcerations of the small intestine or colon, as seen with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and pseudomembranous colitis, can result in severe protein loss.37,38,52 Hypoalbuminemia is common in patients with GI tract malignancies; although this is often the result of a decrease in albumin synthesis, excessive enteric protein loss has been reported. Protein-losing gastroenteropathy also has been related to cancer therapy including chemotherapy, radiation-related injury, and bone marrow transplantation.

DISEASES WITH LYMPHATIC OBSTRUCTION OR ELEVATED LYMPHATIC PRESSURE

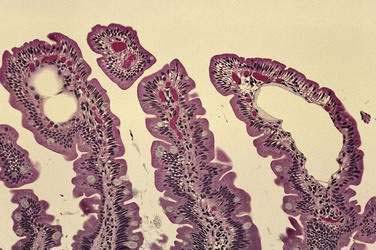

Lymphatic obstruction results in dilation of intestinal lymphatic channels and can result in rupture of lacteals rich in plasma proteins, chylomicrons, and lymphocytes. When central venous pressure is elevated, such as in congestive heart failure or constrictive pericarditis, bowel wall lymphatic vessels become congested, resulting in a loss of protein-rich lymph into the GI tract.54–56 Tortuous, dilated mucosal and submucosal lymphatic vessels are also seen in patients with primary intestinal lymphangiectasias (Fig. 28-3). These patients often present by 30 years of age with edema, hypoproteinemia, diarrhea, and lymphocytopenia from both lymphatic leakage and rupture.58,59 Retroperitoneal processes such as adenopathy, fibrosis, and pancreatitis can also impair lymphatic drainage.

An association between protein-losing gastroenteropathy and heart disease is seen after the Fontan procedure, a surgical correction for a congenital, univentricular heart. The surgery creates a wide anastomosis between the right atrium and pulmonary artery, and protein-losing gastroenteropathy has been noted in up to 15% of patients in the ensuing 10 years.67 Hemodynamic studies in such patients reveal increased central venous pressures.

DIAGNOSIS

LABORATORY TESTS

Because hypoproteinemia and edema are seen in other disorders in addition to protein-losing gastroenteropathy, documentation of excessive protein loss into the GI tract is important. Patients with unexplained hypoproteinemia in the absence of proteinuria, liver disease, and malnutrition should be investigated for evidence of protein-losing gastroenteropathy. The gold standard for diagnosing protein-losing gastroenteropathy, measurement of the fecal loss of radiolabeled, intravenously administered macromolecules such as 51Cr-albumin, has significant limitations, such as exposure to radioactive material and a 6- to 10-day collection period. Therefore, this test is not clinically useful.68

α1-AT is a useful marker of intestinal protein loss. α1-AT is a 50-kd glycoprotein similar in size to albumin (67 kd). α1-AT, like albumin, is synthesized in the liver and is neither actively absorbed nor secreted in the intestine; it is also resistant to luminal proteolysis. α1-AT is normally present in the stool in low concentrations.68–71 Enteric protein loss can be demonstrated by quantifying the concentration of α1-AT in the stool or by measuring its clearance from the plasma; the latter is the more reliable indicator. Therefore, the optimal test is to measure the clearance of α1-AT from the plasma during a 72-hour stool collection, with α1-AT plasma clearance expressed in milliliters/day using this formula:

Plasma clearance of α1-AT can also be used to monitor response to therapy.

An α1-AT clearance in excess of 24 mL/day in patients without diarrhea is abnormal. Diarrhea alone can increase α1-AT clearance; thus, an α1-AT clearance exceeding 56 mL/day in patients with diarrhea is considered abnormal. In addition, there is an inverse correlation between α1-AT plasma clearance and serum albumin concentration; as serum albumin levels fall below 3 g/dL, the clearance of α1-AT exceeds 180 mL/day. In infants, meconium can interfere with α1-AT results (false-positives) because of the higher concentration of α1-AT in meconium and, therefore, this test should not be performed on infants suspected of having protein-losing enteropathy.68–71 Intestinal bleeding also leads to false elevations of α1-AT clearance. In patients who test positive for fecal occult blood, interpretation of α1-AT clearance can be difficult because of increased clearance rates.68–71 Finally, α1-AT is degraded by pepsin at a gastric pH below 3 and thus cannot be relied on to measure gastric protein loss (false-negatives); the use of a proton pump inhibitor to prevent peptic degradation of α1-AT in the stomach may allow detection of protein-losing gastropathy.

Nuclear studies are available to aid in the diagnosis of protein-losing gastroenteropathy; these include technetium-99m (99mTc)–labeled human serum albumin (99mTc-HSA), 99mTc-labeled methylene diphosphonate (99mTc-MDP), 99mTc-labeled dextran scintigraphy, 99mTc-labeled human immunoglobulin, and indium-111 (111In)–labeled transferrin.72–74 Nuclear imaging may be useful to quantify protein loss or localize a site-specific area of protein loss and can be helpful in establishing a diagnosis when the α1-AT clearance results are equivocal. Of these tests, 99mTc-labeled dextran scintigraphy may be more sensitive than 99mTc-HSA, although neither test is widely available. Studies in children and adults have used 99mTc-HSA for detecting the specific site of gastric or enteric protein loss, and this test can also be used to monitor response to therapy. 99mTc-labeled human immunoglobulin and 111In-labeled transferrin also may help quantify and localize protein loss into the GI tract.75,76 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been described as a useful tool for the diagnosis of primary protein-losing gastroenteropathy, readily characterizing lesions that may be associated with protein loss into the gut, such as dilated mesenteric lymphatics in the abdomen and prominent subcutaneous lymphatics in the extremities.77

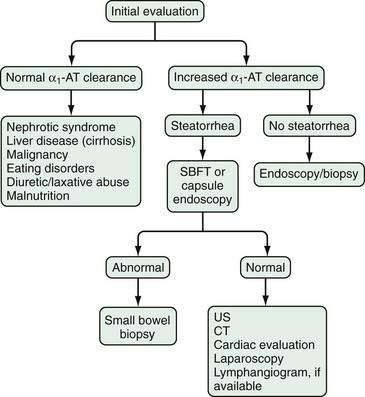

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT WITH SUSPECTED PROTEIN-LOSING GASTROENTEROPATHY

The diagnosis of protein-losing gastroenteropathy is usually made on the basis of an increase in α1-AT clearance, in the absence of confounding variables just discussed, with nuclear testing such as 99mTc-HSA helping confirm and quantitate the extent and location of the disorder in certain patients, and directing the evaluation to a specific organ (Fig. 28-4). Testing to confirm protein loss from the GI tract is critical to establishing the diagnosis of protein-losing gastroenteropathy because many other diseases can present with edema and hypoproteinemia without enteric protein loss. Examples include nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, malignancy, eating disorders including bulimia and anorexia, malnutrition, and diuretic or laxative abuse.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy may help detect mucosal inflammation, ulceration, neoplastic disease, or other abnormalities. Biopsies of abnormal-appearing areas should be taken; random biopsies also may have a yield, because conditions such as collagenous or lymphocytic colitis can appear endoscopically normal. Barium studies of the small and large bowel may demonstrate ulcers and mucosal abnormalities. Disorders that might lead to lymphatic obstruction such as fibrosis, pancreatic diseases, or malignancies can be evaluated by computed tomography or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis. Videocapsule endoscopy is useful in evaluating for protein-losing gastroenteropathy to identify the presence of intestinal lymphangietases.78 Lymphangiography may be considered for selected patients, but this test is rarely performed in most centers. When the diagnosis remains unclear, exploratory laparotomy to exclude the possibility of occult malignancy is sometimes appropriate.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Because protein-losing gastroenteropathy is a syndrome and not a specific disease, treatment is directed at correction of the underlying disease. Protein loss may be offset in part by a high-protein diet, and a diet lower in fat appears to have a beneficial effect on albumin metabolism. Moreover, octreotide may be useful for some patients with protein-losing gastroenteropathy to decrease fluid secretion and protein exudation from the bowel.79

There is some suggestion in experimental mouse models that infusion of heparin analogs may restore intestinal mucosal tight junctions and prevent protein loss across the surface of the bowel; further clinical work is needed to define efficacy.12

For diseases affecting the stomach, such as giant hypertrophic gastropathy (Ménétrier’s disease), gastrectomy reverses protein loss. However, evidence of an infection with H. pylori should be sought before surgical consideration and treated if present (see Chapter 50).41,42 Protein loss from the small bowel should be treated according to the individual disease process present. For example, diseases involving bacterial pathogens such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and Whipple’s disease should be treated with appropriate antibiotic therapy (see Chapters 102 and 106), whereas inflammatory processes such as Crohn’s disease or lupus may require immunosuppressive therapy, including glucocorticoids, budesonide, cyclosporine, or cyclophosphamide, or a combination.30,80,81 In the colon, protein loss seen in diseases such as ulcerative colitis and collagenous colitis may require long-term immunomodulators or surgery, and infectious colitides need antibiotic treatment. Malignancy-induced enteric protein loss requires cancer-specific therapy. Enteric protein loss and lymphocytopenia seen in cardiac diseases (e.g., congestive heart failure and constrictive pericarditis) can be ameliorated with medical and surgical management of the underlying cardiac condition.55,67,82

Acquired intestinal lymphangiectasia should be treated by correction of the primary disease, whereas congenital intestinal lymphangiectasia can be partially controlled with dietary restrictions. Enteric protein loss in patients with the latter condition can be reduced by a low-fat diet enriched with medium-chain triglycerides, which do not require lymphatic transport and therefore do not stimulate lymph flow.83

Most causes of the protein-losing disorders of the GI tract are easily detectable and treatable, and many can be cured. As such, the goal of therapy in protein-losing gastroenteropathy is to identify the cause and direct dietary, medical, or surgical intervention, or a combination, at the underlying disease.8 With reversal or control of the primary disease, a significant proportion of patients will have a partial or complete remission of enteric protein loss, edema, and other associated conditions.

Bode L, Salvestrini C, Park PW, et al. Heparan sulfate and syndecan-1 are essential in maintaining murine and human intestinal epithelial barrier function. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:229-38. (Ref 10.)

Freeman HJ, Sleisenger MH, Kim YS. Human protein digestion and absorption: Normal mechanisms and protein-energy malnutrition. Clin Gastroenterol. 1983;12:357-78. (Ref 6.)

Landzberg BR, Pochapin MB. Protein-losing enteropathy and gastropathy. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4:39-49. (Ref 8.)

Lencer WI. Patching a leaky intestine. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:526-8. (Ref 11.)

Rychik J. Protein-losing enteropathy after Fontan operation. Congenit Heart Dis. 2007;2:288-300. (Ref 56.)

Sato T, Chiguchi G, Inamori M, et al. Protein-losing gastroenteropathy and gastric polyps: Successful treatment by Helicobacter pylori eradication. Digestion. 2007;75:99. (Ref 42.)

Strygler B, Nicar MJ, Santangelo WC, et al. Alpha 1-antitrypsin excretion in stool in normal subjects and in patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1380-7. (Ref 70.)

Takeda H, Ishihama K. Fukui T, et al. Significance of rapid turnover proteins in protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1963-5. (Ref 64.)

Touibia N, Schubert ML. Menetrier’s disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2008;11:103-8. (Ref 22.)

Wang S, Tsai S, Lan J. Tc-99m albumin scintigraphy to monitor the effect of treatment in protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:197-9. (Ref 72.)

Yazici Y, Erkan D, Levine DM, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: Report of a severe, persistent case and review of pathophysiology. Lupus. 2002;11:119-23. (Ref 29.)

1. Albright F, Bartter FC, Forbes AP. The fate of human serum albumin administered intravenously to a patient with idiopathic hypoalbuminemia and hypoproteinemia. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1949;204:62.

2. Citrin Y, Sterling K, Halsted JA. The mechanism of hypoproteinemia associated with giant hypertrophy of the gastric mucosa. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:906-12.

3. Gordon RSJr. Exudative enteropathy: Abnormal permeability of the gastrointestinal tract demonstrable with labeled polyvinylpyrrolidone. Lancet. 1959;1:325-6.

4. Waldmann TA. Protein-losing enteropathy. Gastroenterology. 1966;50:422-43.

5. Strygler B, Nicar MJ, Santangelo WC, et al. Alpha1-antitrypsin excretion in stool in normal subjects and in patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1380-7.

6. Freeman HJ, Sleisenger MH, Kim YS. Human protein digestion and absorption: Normal mechanisms and protein-energy malnutrition. Clin Gastroenterol. 1983;12:357-78.

7. Waldmann TA, Wochner RD, Srober W. The role of the gastrointestinal tract in plasma protein metabolism. Am J Med. 1969;46:275-85.

8. Landzberg BR, Pochapin MB. Protein-losing enteropathy and gastropathy. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4:39-49.

9. Wochner RD, Weissman SM, Waldmann TA, et al. Direct measurement of the rates of synthesis of plasma proteins in control subjects and patients with gastrointestinal protein loss. J Clin Invest. 1968;47:971-82.

10. Bode L, Salvestrini C, Park PW, et al. Heparan sulfate and syndecan-1 are essential in maintaining murine and human intestinal epithelial barrier function. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:229-38.

11. Lencer WI. Patching a leaky intestine. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:526-8.

12. Morgan MR, Humphries MJ, Bass MD. Synergistic control of cell adhesion by integrins and syndecans. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:957-69.

13. Laine L, Garcia F, McGilligan K, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy and hypoalbuminemia in AIDS. AIDS. 1993;7:837-40.

14. Schreiber DS, Blacklow NR, Trier JS. The mucosal lesion of the proximal small intestine in acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:1318-23.

15. Waldmann TA, Wochner RD, Laster L, Gordon RSJr. Allergic gastroenteropathy: A cause of excessive protein loss. N Engl J Med. 1967;276:762-9.

16. Bai JC, Sambuelli A, Niveloni S, et al. Alpha 1-antitrypsin clearance as an aid in the management of patients with celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:986-91.

17. Ellaway CJ, Christodoulou R, Kamath K, et al. The association of protein-losing enteropathy with cobalamin C defect. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21:17-22.

18. Stark ME, Batts KP, Alexander GL. Protein-losing enteropathy with collagenous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:780-3.

19. Suter WR, Neuwieiler J, Borovicka J, et al. Cytomegalovirus-induced transient protein-losing hypertrophic gastropathy in an immunocompetent adult. Digestion. 2000;62:276-9.

20. Fenoglio LM, Benedetti V, Rossi C, et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis with ascites. A case report and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1013-20.

21. Overholt BF, Jeffries GH. Hypertrophic, hypersecretory protein-losing gastropathy. Gastroenterology. 1970;58:80-7.

22. Touibia N, Schubert ML. Menetrier’s disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2008;11:103-8.

23. Reif S, Jain A, Santiago J, Rossi T. Protein-losing enteropathy as a manifestation of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:482-5.

24. Sullivan PB, Lunn PG, Northrop-Clewes CA, Farthing MJ. Parasitic infection of the gut and protein-losing enteropathy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992;15:404-7.

25. el Aggan HA, Marzouk S. Fecal alpha 1-antitrypsin concentration in patients with schistosomal hepatic fibrosis. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1992;22:195-203.

26. Dubey R, Bavdekar SB, Muranjan M, et al. Intestinal giardiasis: An unusual cause for hypoproteinemia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2000;19:38-9.

27. Su J, Smith MB, Rerknimitr R, Morrow D. Small intestine bacterial overgrowth presenting as protein-losing enteropathy. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:679-81.

28. Molina JF, Brown A, Gedalia A, Espinoza LR. Protein-losing enteropathy as the initial manifestation of childhood systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1269-71.

29. Yazici Y, Erkan D, Levine DM, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: Report of a severe, persistent case and review of pathophysiology. Lupus. 2002;11:119-23.

30. Werner de Castro GR, Appenzeller S, Bertolo MB, Costallat LT. Protein-losing enteropathy associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: Response to cyclophosphamide. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:135-8.

31. Rubini ME, Sheehy TW, Meroney WH, Louro J. Exudative enteropathy II. Observations in tropical sprue. J Lab Clin Med. 1961;58:902-7.

32. Bak YT, Kwon OS, Kim JS, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy with an endoscopic feature of “the watermelon colon.”. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:565-7.

33. Laster L, Waldman TA, Fenster LF, et al. Reversible enteric protein loss in Whipple’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1962;42:762.

34. Roth S, Havemann K, Kalbfleisch H, et al. Alpha-chain disease presenting as malabsorption syndrome with exudative enteropathy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1976;101:1823-8.

35. Kawaguchi M, Koizumi F, Shimao M, Hirose S. Protein-losing enteropathy due to secondary amyloidosis of the gastrointestinal tract. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1993;43:333-9.

36. Morita A, Asakura H, Morishita T, et al. Lymphangiographic findings in Behçet’s disease with lymphangiectasia of the small intestine. Angiology. 1976;27:622-33.

37. Ferrante M, Penninckx F, De Hertogh G, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy in Crohn’s disease. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2006;69:384-9.

38. Hundegger K, Stufler M, Karbach U. Enteric protein loss as a marker of intestinal inflammatory activity in Crohn’s disease: Comparability of enteric clearance and stool concentration of alpha1-antitrypsin? Z Gastroenterol. 1992;30:722-8.

39. Murata I, Yoshikawa I, Kuroda T, et al. Varioliform gastritis and duodenitis associated with protein-losing gastroenteropathy, treated with omeprazole. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:109-13.

40. Weisdorf SA, Salati LM, Longsdorf JA, et al. Graft-versus-host disease of the intestine: A protein-losing enteropathy characterized by fecal alpha1-antitrypsin. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:1076-81.

41. Di Vita G, Patti R, Aragona F, et al. Resolution of Ménétrier’s disease after Helicobacter pylori eradicating therapy. Dig Dis. 2001;19:179-83.

42. Sato T, Chiguchi G, Inamori M, et al. Protein-losing gastroenteropathy and gastric polyps: Successful treatment by Helicobacter pylori eradication. Digestion. 2007;75:99.

43. Yoshikawa I, Murata I, Tamura M, et al. A case of protein-losing gastropathy caused by acute Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:245-8.

44. Schaad U, Zimmerman A, Gaze H, Hadorn B. Protein-losing enteropathy due to segmental erosive and ulcerative intestinal disease cured by limited resection of the bowel. Helvet Paediatr Acta. 1978;33:289-97.

45. Barlett JG. Clostridium difficile infection: Pathophysiology and diagnosis. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1997;8:12-21.

46. Bennish ML, Salam MA, Wahed MA. Enteric protein loss during shigellosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:53-7.

47. Laine L, Politoske EJ, Gill P. Protein-losing enteropathy in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome due to intestinal Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1174-5.

48. Tatemichi M, Nagata H, Morinaga S, Kaneda S. Protein-losing enteropathy caused by mesenteric vascular involvement of neurofibromatosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1549-53.

49. Bjarnason I, Hayllar J, MacPherson AJ, Russell AS. Side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the small and large intestines in humans. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1832-47.

50. Popovic OS, Brkic S, Bojic P, et al. Sarcoidosis and protein-losing enteropathy. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:119-25.

51. Tasaki K, Sasaki M, Bamba M, et al. A case of toxic shock–like syndrome presenting with serious hypoproteinemia because of a protein-losing gastroenteropathy. J Intern Med. 2001;250:174-9.

52. Anderson R, Kaariainen I, Hanauer S. Protein-losing enteropathy and massive pulmonary embolism in a patient with giant inflammatory polyposis and quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 1996;101:323-5.

53. Pratz KW, Dingli D, Smyrk TC, Lust JA. Intestinal lymphangiectasia with protein-losing enteropathy in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Medicine. 2007;86:210-14.

54. Chan FK, Sung JJ, Ma KM, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy in congestive heart failure: Diagnosis by means of a simple method. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1816-18.

55. Ohsawa M, Nakamura M, Pan LH, et al. Post-operative constrictive pericarditis complicated with lymphocytopenia and hypoglobulinemia. Intern Med. 2004;43:811-15.

56. Rychik J. Protein-losing enteropathy after Fontan operation. Congenit Heart Dis. 2007;2:288-300.

57. Henley JD, Kratzer SS, Seo IS, Davis T. Endometriosis of the small intestine presenting as a protein-losing enteropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:130-3.

58. Asakura H, Miura S, Morishita T, et al. Endoscopic and histopathological study on primary and secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:312-20.

59. Mistilis SP, Skyring AP, Stephen DD. Intestinal lymphangiectasia: Mechanism of enteric loss of plasma protein and fat. Lancet. 1965;1:77-9.

60. Matsushita I, Hanai H, Sato Y, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy caused by mesenteric venous thrombosis with protein C deficiency. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:94-7.

61. Conn HO. Is protein-losing enteropathy a significant complication of portal hypertension? Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:127-8.

62. Younes B, Ament M, McDiarmid S, et al. The involvement of the gastrointestinal tract in post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in pediatric liver transplantation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:380-5.

63. Höring E, Hingerl T, Hens K, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy: First manifestation of sclerosing mesenteritis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:481-3.

64. Takeda H, Ishihama K, Fukui T, et al. Significance of rapid turnover proteins in protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1963-5.

65. Venkatramani J, Gottlieb JL, Thomassen TS, Multari A. Bilateral serous retinal detachment due to protein-losing enteropathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1067-70.

66. Müller C, Wolf H, Göttlicher J, et al. Cellular immunodeficiency in protein-losing enteropathy: Predominant reduction of CD3+ and CD4+ lymphocytes. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:116-22.

67. Rychik J. Protein-losing enteropathy after Fontan operation. Congenit Heart Dis. 2007;2:288-300.

68. Magazzu G, Jacono G, Di Pasquale G, et al. Reliability and usefulness of random fecal alpha 1-antitrypsin concentration: Further simplification of the method. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4:402-7.

69. Hill RE, Hercz A, Corey ML, et al. Fecal clearance of alpha 1-antitrypsin: A reliable measure of enteric protein loss in children. J Pediatr. 1981;99:416-18.

70. Strygler B, Nicar MJ, Santangelo WC, et al. Alpha 1-antitrypsin excretion in stool in normal subjects and in patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1380-7.

71. Takeda H, Nishise S, Furukawa M, et al. Fecal clearance of alpha 1-antitrypsin with lansoprazole can detect protein-losing gastropathy. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:2313-18.

72. Wang S, Tsai S, Lan J. Tc-99m albumin scintigraphy to monitor the effect of treatment in protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:197-9.

73. Halaby H, Bakheet SM, Shabib S. 99mTc-human serum albumin scans in children with protein-losing enteropathy. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:215-19.

74. Uzuner O, Ziessman HA. Protein-losing enteropathy detected by Tc-99m-MDP abdominal scintigraphy. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:1122-4.

75. Yueh T, Pui MH, Zend SQ. Intestinal lymphangiectasia. Value of Tc-99m dextran lymphoscintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 1997;22:695-6.

76. de Kaski MC, Peters AM, Bradley D, Hodgson HJ. Detection and quantification of protein-losing enteropathy with indium-111 transferrin. Eur J Nucl Med.. 1996;23:530-3.

77. Liu NF, LU Q, Wang CG, Zhou JG. Magnetic resonance imaging as a new method to diagnose protein-losing enteropathy. Lymphology. 2008;41:111-15.

78. Chamouard P, Nehme-Schuster H, Simler JM, et al. Videocapsule endoscopy is useful for the diagnosis of intestinal lympangiectasia. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:699-703.

79. Lee HL, Han DS, Kim JB, et al. Successful treatment of protein-losing enteropathy induced by intestinal lymphangiectasia in a liver cirrhosis patient with octreotide: A case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:466-9.

80. Aoki T, Noma N, Takajo I, et al. Protein-losing gastropathy associated with autoimmune disease: Successful treatment with prednisolone. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:204-9.

81. Sunagawa T, Kinjo F, Gakiya I, et al. Successful long-term treatment with cyclosporin A in protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Intern Med. 2004;43:397-9.

82. Masetti P, Marianeschi SM, Capriani A, et al. Reversal of protein-losing enteropathy after ligation of systemic-pulmonary shunt. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:235-6.

83. Alfano V, Tritto G, Alfonsi L, et al. Stable reversal of pathologic signs of primitive intestinal lymphangiectasia with a hypolipidic, MCT-enriched diet. Nutrition. 2000;16:303-4.