Protection From Blood-Feeding Arthropods

Of all the hazards, large and small, that may befall the outdoor enthusiast, perhaps the most vexatious comes from the smallest perils—blood-feeding arthropods. Mosquitoes, flies, fleas, mites, midges, chiggers, and ticks all readily bite humans (Box 39-1).

Personal Protection

Personal protection against insect bites can be achieved in three ways:

Habitat Avoidance

Avoiding infested habitats reduces the risk for being bitten.

1. Mosquitoes and other nocturnal bloodsuckers are particularly active at dusk, making this a good time to be indoors.

2. To avoid the usual resting places of biting arthropods, campgrounds should be situated in areas that are high, dry, open, and as free from vegetation as possible.

3. Areas with standing or stagnant water should be avoided, because these are ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

4. Attempts should be made to avoid unnecessary use of lights, which attract many insects.

Physical Protection

1. Physical barriers can be extremely effective in preventing insect bites, by blocking arthropods’ access to the skin.

2. Long-sleeved shirts, socks, long pants, and a hat will protect all but the face, neck, and hands.

3. Tucking pants into the socks or boots makes it much more difficult for ticks or chigger mites to gain access to the skin.

4. Light-colored clothing is preferable because it makes it easier to spot ticks, and it is less attractive to mosquitoes and biting flies.

5. Ticks will find it more difficult to cling to smooth, tightly woven fabrics (e.g., nylon).

6. Loose-fitting clothing, made out of tightly woven fabric, with a tucked-in T-shirt undergarment is particularly effective at reducing bites on the upper body.

7. A light-colored, full-brimmed hat will protect the head and neck.

a. Deerflies tend to land on the hat instead of the head.

b. Blackflies and biting midges are less likely to crawl to the shaded skin beneath the brim.

8. Mesh garments or garments made of tightly woven material are available to protect against insect bites.

a. Head nets, hooded jackets, pants, and mittens are available from a number of manufacturers in a wide range of sizes and styles (Box 39-2).

b. With a mesh size of less than 0.3 mm (0.01 inch), many of these garments are woven tightly enough to exclude even biting midges and ticks.

c. As with any clothing, bending or crouching may still pull the garments close enough to the skin surface to enable insects to bite through.

d. Shannon Outdoors addresses this potential problem with a double-layered mesh that reportedly prevents mosquito penetration.

e. Although mesh garments are effective barriers against insects, some people may find them uncomfortable during vigorous activity or in hot weather.

9. Lightweight insect nets and mesh shelters are available to protect travelers sleeping indoors or in the wilderness (see Box 39-2).

Repellents

1. Development of the perfect insect repellent has been a scientific goal for years and has yet to be achieved.

2. The ideal agent would repel multiple species of biting arthropods, remain effective for at least 8 hours, cause no irritation to skin or mucous membranes, and possess no systemic toxicity, and it would be resistant to abrasion, greaseless, odorless, and not easily washed off.

3. No commercially available insect repellent meets all of these criteria.

4. Repellents do not all share a single mode of action, and different species of insects may react differently to the same repellent.

5. To be effective as an insect repellent, a chemical must be volatile enough to maintain an effective repellent vapor concentration at the skin surface, but it must not evaporate so rapidly that it quickly loses its effectiveness.

6. Multiple factors play a role in effectiveness, including concentration, frequency and uniformity of application, the user’s activity level and overall attractiveness to blood-sucking arthropods, and the number and species of the organisms trying to bite.

7. The effectiveness of any repellent is reduced by abrasion from clothing; by evaporation from and absorption into the skin surface; by its tendency to be washed off via sweat, rain, or water; and by a windy environment.

8. Each 18° F (10° C) increase in ambient temperature can lead to as much as a 50% reduction in protection time.

9. Insect repellents do not cloak the user in a chemical veil of protection; any untreated exposed skin can be readily bitten by hungry arthropods.

Chemical Repellents

DEET

1. N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (previously called N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide), or DEET, remains the gold standard of presently available insect repellents.

2. DEET has been registered for use by the general public since 1957. It is a broad-spectrum repellent, effective against many species of crawling and flying insects, including mosquitoes, biting flies, midges, chiggers, fleas, and ticks.

3. DEET may be applied directly to skin, clothing, mesh insect nets or shelters, window screens, tents, or sleeping bags.

4. Care should be taken to avoid inadvertent contact with plastics (e.g., watch crystals, eyeglass frames), rayon, spandex, leather, or painted and varnished surfaces because DEET may damage these. DEET does not damage natural fibers like wool and cotton.

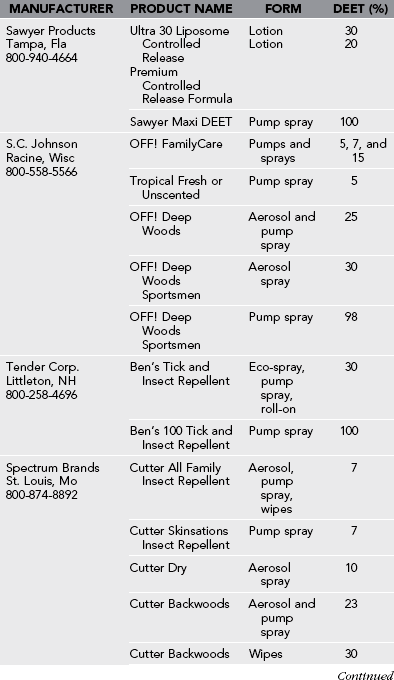

5. In the United States, DEET is sold in concentrations from 5% to 100% in multiple formulations, including lotions, solutions, gels, sprays, roll-ons, and impregnated towelettes (see Table 39-1).

6. As a general rule, higher concentrations of DEET provide longer-lasting protection. For most uses, however, there is no need to use the highest concentrations of DEET.

7. Products with 10% to 35% DEET provide adequate protection under most conditions. In fact, most manufacturers, responding to consumer demand, offer a greater variety of low-concentration DEET products, and the vast majority of products now contain DEET concentrations of 35% or less.

8. Persons averse to applying DEET directly to their skin may get long-lasting repellency by applying it only to their clothing.

9. DEET-treated garments, stored in a plastic bag between wearings, maintain their repellency for several weeks.

10. Products with a DEET concentration higher than 35% are probably best reserved for circumstances in which the wearer will be in an environment with a high density of insects (e.g., a rain forest), where there is a high risk for disease transmission from insect bites, or when there may be rapid loss of repellent from the skin surface, such as under conditions of high temperature and humidity or rain. Under these circumstances, reapplication of the repellent will most likely be necessary to maintain its effectiveness.

11. Sequential application of a DEET-based repellent and a sunscreen can reduce the efficacy of the sunscreen. In one study of persons who applied a 33% DEET repellent followed by a sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 15, the sunscreen’s SPF was decreased by a mean of 33%, although the repellent maintained its potency.

12. Some products contain a combination of sunscreen and DEET and will deliver the SPF stated on the label. However, these products are generally not the best choice because it is rare that the need for reapplication of sunscreen and repellent is exactly the same.

13. 3M and Sawyer Products currently manufacture extended-release formulations of DEET that make it possible to deliver long-lasting protection without relying on high concentrations.

a. The 3M product Ultrathon is an acrylate polymer formulation containing 35% DEET and is as effective as 75% DEET, providing up to 12 hours of greater than 95% protection against mosquito bites.

b. Sawyer Products’ controlled-release 20% DEET lotion traps the chemical in a protein particle that slowly releases it to the skin surface, providing repellency equivalent to a standard 50% DEET preparation and lasting about 5 hours. Compared with a 20% ethanol-based preparation of DEET, 60% less of this encapsulated DEET is absorbed.

14. Case reports of potential DEET toxicity exist in the medical literature and have been extensively reviewed.

a. Fewer than 50 cases of significant toxicity from DEET exposure have been documented in the medical literature; more than three-quarters of these resolved without sequelae.

b. Many of these cases involved long-term, excessive, or inappropriate use of DEET repellents

c. Multiple studies have confirmed that children are not at greater risk for developing adverse effects from DEET when compared with older individuals.

d. In studies of DEET in pregnancy, no differences in survival, growth, or neurologic development have been detected in infants born to mothers who used DEET.

e. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has issued guidelines to ensure safe use of DEET-based repellents (Box 39-3). Careful product choice and common sense application greatly reduce the possibility of toxicity.

f. The current recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics is that children older than the age of 2 months can safely use up to 30% DEET. When required, reapplication of a low-strength repellent can compensate for the inherent shorter duration of protection.

g. Questions about the safety of DEET may be addressed to the EPA-sponsored National Pesticide Information Center, available daily from 7:30 AM to 3:30 PM PST at 800-858-7378, or via their website at http://npic.orst.edu.

IR3535 (Ethyl Butylacetylaminoproprionate)

1. IR3535 is an analog of the amino acid β-alanine and has been sold in Europe as an insect repellent for more than 20 years.

2. In the United States this compound is classified by the EPA as a biopesticide, effective against mosquitoes, ticks, and flies.

3. IR3535 was brought to the U.S. market in 1999 and sold by Avon Products, Inc and Sawyer Products in concentrations from 7.5% to 20%, with and without sunscreen.

4. Depending on the species of mosquito and the testing method, this repellent has demonstrated widely variable effectiveness, with complete protection times ranging from 23 to 360 minutes.

5. In general, IR3535 provides longer-lasting repellency than the botanical citronella-based repellents, but it does not match the overall efficacy of DEET.

6. In 2008 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a statement adding IR3535 to the list of approved repellents that could be used effectively to prevent mosquito-borne diseases.

Picaridin

1. The piperidine derivative picaridin (also known as KBR 3023) is the newest insect repellent to become available in the United States.

2. Picaridin-based insect repellents have been sold in Europe since 1998 under the brand name Bayrepel.

3. This nearly odorless, nongreasy repellent is effective against mosquitoes, biting flies, and ticks.

4. Studies have shown that, when used at higher concentrations of up to 20%, picaridin repellents can offer an efficacy comparable to that of DEET, giving up to 8 hours of protection.

5. The chemical is aesthetically pleasant and, unlike DEET, shows no detrimental effects on contact with plastics.

6. The EPA found picaridin to have a low toxicity risk.

7. Picaridin is superior to DEET as a tick repellent.

8. In April 2005 the CDC released a statement adding picaridin to the list of approved repellents that could be used effectively to prevent mosquito-borne diseases.

Botanical Repellents

1. Thousands of plants have been tested as sources of insect repellents.

2. Although none of the currently available plant-derived chemicals tested to date demonstrates the broad effectiveness and duration of DEET, a few show repellent activity.

3. The CDC is working with nootkatone, a naturally occurring nontoxic chemical found in Alaska yellow cedar trees and citrus fruit, that has show great promise as both an insecticide and repellent.

4. Other plants with essential oils that have been reported to possess repellent activity include citronella, neem, cedar, verbena, pennyroyal, geranium, catnip, lavender, pine, cajeput, cinnamon, vanilla, rosemary, basil, thyme, allspice, garlic, and peppermint. When tested, most of these essential oils tended to show short-lasting protection, lasting minutes to 2 hours.

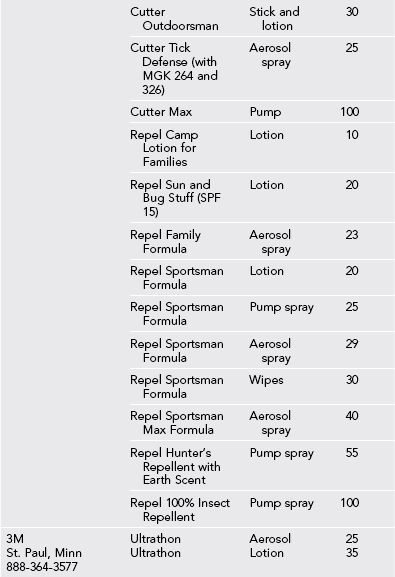

5. A summary of readily available plant-derived insect repellents is shown in Table 39-2.

Citronella

1. It is the most common active ingredient found in “natural” or “herbal” insect repellents presently marketed in the United States.

2. Conflicting data exist on the efficacy of citronella-based products, varying greatly depending on the study methodology, location, and species of biting insect tested.

3. Citronella-based lotions, in which the essential oil has been encapsulated into a beeswax matrix, slowly release the oil to the skin surface, prolonging efficacy.

4. In general, studies show that citronella-based repellents are less effective than are DEET repellents.

5. Citronella provides a shorter protection time (in some studies, 40 minutes to 2 hours), which may be partially overcome by frequent reapplication of the repellent.

6. The EPA concluded that citronella-based insect repellents must contain the following statement on their labels: “For maximum repellent effectiveness of this product, repeat applications at 1-hour intervals.”

7. Citronella candles have been promoted as an effective way to repel mosquitoes from one’s local environment.

a. In one study, subjects near the citronella candles had 42% less bites than controls that had no protection (a statistically significant difference). However, burning ordinary candles reduced the number of bites by 23%.

b. The ability of plain candles to decrease biting may be due to their serving as a decoy source of warmth, moisture, and carbon dioxide.

Bite Blocker

1. Bite Blocker is a “natural” repellent that combines soybean oil, geranium oil, and coconut oil in a formulation.

2. Studies showed that this product was capable of providing more than 97% protection against Aedes species mosquitoes under field conditions, even 3.5 hours after application. Bite Blocker provides a mean of 200 ± 30 minutes of complete protection from mosquito bites.

3. Laboratory studies using three different species of mosquitoes showed that Bite Blocker provided an average protection time of about 7 hours, and about 10 hours of protection against biting blackflies

Lemon Eucalyptus

1. A eucalyptus derivative (p-menthane-3,8-diol, or PMD) isolated from oil of the lemon eucalyptus plant has a strong lemony scent and has shown promise as an effective “natural” repellent.

2. Field tests of this repellent have shown mean complete protection times ranging from 4 to 8 hours, depending on the mosquito species.

3. PMD-based repellents can cause significant ocular irritation, so care must be taken to keep them away from the eyes. They should not be used in children younger than 3 years.

Insecticides

1. Pyrethrum is a powerful, rapidly acting insecticide originally derived from crushed dried flowers of the daisy Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium.

2. It is effective against mosquitoes, flies, ticks, fleas, lice, and chiggers. It does not repel insects but works as a contact insecticide, causing nervous system toxicity, leading to death, or “knockdown,” of the insect.

3. Permethrin has low mammalian toxicity, is poorly absorbed by the skin, and is rapidly metabolized by skin and blood esterases.

4. Permethrin should be applied directly to clothing or to other fabrics (tent walls or mosquito nets), not to skin.

5. Permethrin is nonstaining, is nearly odorless, is resistant to degradation by heat or sun, and maintains its effectiveness for at least 2 weeks and through several launderings.

6. The combination of permethrin-treated clothing and skin application of a DEET-based repellent creates a formidable barrier against biting insects.

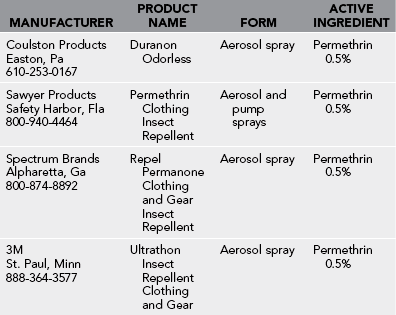

7. Permethrin-based insecticides available in the United States are listed in Table 39-3.

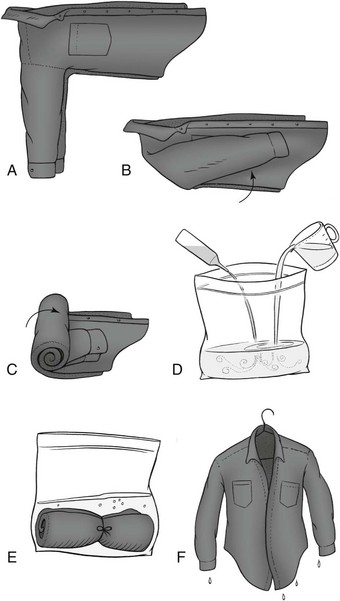

8. To apply to clothing do the following:

a. Spray each side of the fabric (outdoors) for 30 to 45 seconds, just enough to moisten the fabric.

9. Permethrin solution is also available for soak-treating large items such as mesh bed nets or for treating multiple garments simultaneously (see Fig. 39-1).

10. Permethrin-pretreated shirts, pants, socks, and hats can also be purchased.

Reducing Local Mosquito Populations

1. Multiple studies, conducted in the field and in the laboratory, show that these devices do not work.

2. Mass-marketed backyard “bug zappers,” which use ultraviolet light to lure and electrocute insects, are also ineffective: Mosquitoes continue to be more attracted to humans than to the devices.

3. DEET-impregnated wristbands offer no protection against mosquito bites, but in one study, wearing impregnated anklets, wristbands, shoulder strips, and pocket strips provided up to 5 hours of complete protection.

4. Using more specific bait such as a warm, moist plume of carbon dioxide, as well as other known chemical attractants (e.g., octenol), may prove to be a more successful way to lure and selectively kill biting insects.

5. Pyrethrin-containing yard foggers set off before an outdoor event can temporarily reduce the number of biting arthropods in a local environment. These products should be applied before any food is brought outside and should be kept away from animals or fishponds.

6. Burning coils that contain natural pyrethrins or synthetic pyrethroids (such as D-allethrin or D–trans-allethrin) can also temporarily reduce local populations of biting insects. Some concerns have been raised about the cumulative safety of long-term use of these coils in an indoor environment.

7. Wood smoke from campfires can also reduce the likelihood of being bitten by mosquitoes. The smoke’s ability to repel insects may vary depending on the type of wood or vegetation burned.

Integrated Approach to Personal Protection

1. Maximal protection is best achieved through avoiding infested habitats and using protective clothing, topical insect repellents, and permethrin-treated garments.

2. When appropriate, mesh bed nets or tents should be used to prevent nocturnal insect bites.

3. DEET-containing insect repellents are the most effective products currently on the U.S. market, providing broad-spectrum, long-lasting repellency against multiple arthropod species.

4. The CDC has approved picaridin, IR3535, and oil of lemon eucalyptus as alternative repellents that can be used to reduce the likelihood of contracting insect-borne disease.

5. Insect repellents alone, however, should not be relied on to provide complete protection.

a. Mosquitoes, for example, can find and bite any untreated skin and may even bite through thin clothing.

b. Deerflies, biting midges, and some blackflies prefer to bite around the head and readily crawl into the hair to bite where there is no protection.

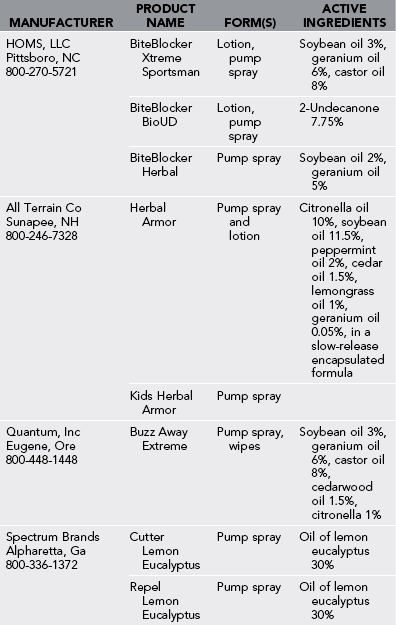

6. Wearing protective clothing, including a hat, reduces the chances of being bitten.

7. Treating clothes, including the hat, with permethrin maximizes their effectiveness by causing knockdown of any insect that crawls or lands on the treated clothing.

8. To prevent chiggers or ticks from crawling up the legs, pants should be tucked into the boots or stockings.

9. Persons traveling to parts of the world where insect-borne disease is a potential threat can protect themselves best if they learn about indigenous insects and the diseases they might transmit. This information may be found at http://www.cdc.gov/travel/index.htm.

Ticks

Awareness of ticks and the diseases they transmit is a necessary first step in prevention.

1. Proper clothing should be light colored, because this makes ticks easier to spot.

2. Avoiding heavily infested areas reduces exposure, as does reducing contact with leaf litter.

3. Boots provide better protection than do tennis shoes and socks. Tucking pant legs into the tops of the socks reduces the ticks’ ability to climb up the legs of potential hosts. A ring of masking tape or duct tape at the tops of the socks further reduces exposure.

4. Topical DEET and permethrin-impregnated gear and clothing round out an effective protection strategy against ticks.

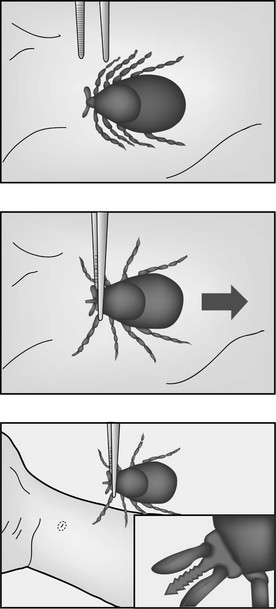

2. Gently grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible, and gradually retract it outward in a straight line (Fig. 39-2).

3. The area should then be cleaned with a local antiseptic.

4. Other methods for tick removal, such as applying petroleum jelly to the tick, or using a lighted match or cigarette, isopropyl alcohol, or fingernail polish, do not ease removal of the tick. These and other “remedies” most likely increase expression of tick saliva and foregut contents, thus increasing the chance of disease transmission.

5. Removal of larval ticks is easier, because their size and mouthparts are extremely tiny. A piece of tape, such as duct tape, applied to the skin and then removed, easily removes free-crawling or attached larval ticks. Alternatively, the thin edge of a plastic object such as a credit card or driver’s license scraped along the skin easily removes attached larvae. This method is appropriate only for larval ticks, not for nymphs or adults.