Chapter 32

Prosthetic Heart Valves

1. What are important considerations in the preoperative evaluation and planning of patients who are to undergo valve repair or replacement?

2. What types of prosthetic valves are used for valve replacement, and which ones are most commonly used in current practice?

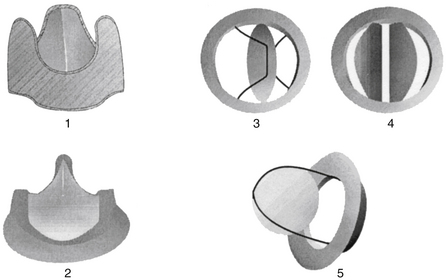

Representative bioprosthetic and mechanical heart valve types are shown in Figure 32-1 and discussed here.

Figure 32-1 Bioprosthetic and mechanical heart valves. (1) Biologic nonstented and (2) stented valves; (3) mechanical single tilting disc valve, (4) mechanical bileaflet valve, and (5) ball-in-cage valve.

A stentless bioprosthesis is a bovine or porcine heart valve implanted without a frame. In the aortic position, the aortic root is used to attach the valve. The major advantage is that the size of the implanted valve can be larger, because no space is required for a supporting frame. Data suggest that left ventricular function is better protected by nonstented compared with stented valves. Anticoagulation is recommended for the first 3 months after implantation.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has been performed at investigational sites for nearly 10 years, mostly commonly in Europe. In the United States, it has recently been approved, though programs that can implant such valves must meet strict standards. It is intended for patients with severe aortic stenosis who are not good surgical candidates for conventional valve replacement. The valve is implanted via a transarterial (femoral or axillary) or transapical approach. In Europe, the valve may also be implanted by a direct aortic approach. Significant risks of serious adverse events, such as valve displacement, cardiac tamponade, myocardial infarction, stroke, or injury of the aorta or femoral or axillary artery, are associated with this procedure. The procedure is illustrated in Figure 32-2.

Figure 32-2 Transcatheter aortic valve replacement. After balloon valvuloplasty of the stenotic aortic valve, the prosthetic valve is positioned at the level of the aortic annulus. The balloon is inflated, deploying the stented valve in position.

3. What is a heterograft, and what is an allograft (homograft), and what is a Ross procedure?

A heterograft is a biologic valve derived from an animal. An allograft (also called a homograft) is a heart valve taken from a human cadaver. Allografts have the advantage of natural configuration and the fact that they include a portion of the aortic root that can be incorporated in the valve replacement procedure if necessary (e.g., aortic root abscess). Careful matching of allograft size to the patient is critical to the performance and durability of the valve. The Ross procedure uses the patient’s own pulmonic valve to replace their aortic valve. The pulmonic valve is then replaced with a bioprosthesis. Advantages are a lack of antigenicity and the potential for growth of the valve over time, as required in children.

4. How does one choose between bioprosthetic and mechanical valves?

5. What are the anticoagulation strategies for patients with prosthetic valves, and what are the risks for thromboembolic or hemorrhagic events?

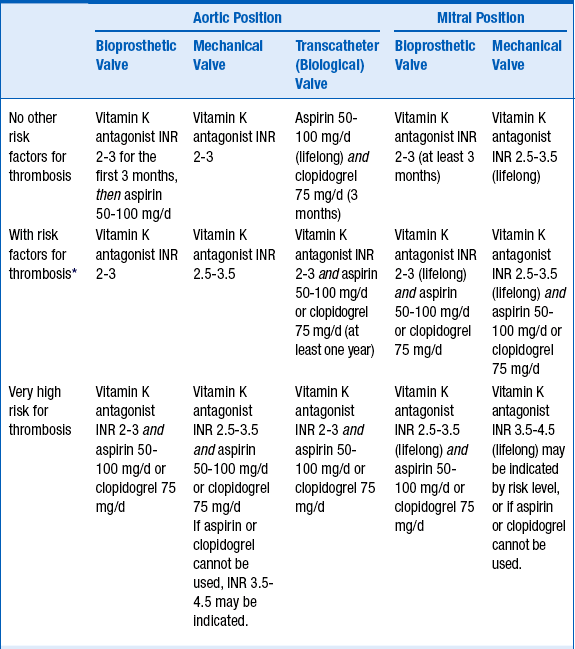

The degree and type of anticoagulation depends on the valve type and location, and the overall risk of thrombosis. Guidelines on anticoagulation of prosthetic heart valves have been published by both the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP). Suggested anticoagulation regimens are given in Table 32-1.

TABLE 32-1

SUGGESTED ANTICOAGULATION REGIMENS AFTER AORTIC AND MITRAL VALVE REPLACEMENT

INR, International normalized ratio.

∗Risk factors such as atrial fibrillation, left ventricular dysfunction, or hypercoagulable state

6. How does one handle anticoagulation issues in patients with mechanical valve prostheses before elective surgery or invasive procedures?

7. How are anticoagulation issues managed when patients with mechanical heart valves become pregnant?

Treatment with LMWH or UFH between weeks 6 and 12 and close to term; warfarin during the rest of the pregnancy

Treatment with LMWH or UFH between weeks 6 and 12 and close to term; warfarin during the rest of the pregnancy

Treatment with UFH throughout the whole pregnancy (subcutaneous UFH 17,500-20,000 U twice a day; aPTT between 55 and 70 seconds by 6 hours after injection)

Treatment with UFH throughout the whole pregnancy (subcutaneous UFH 17,500-20,000 U twice a day; aPTT between 55 and 70 seconds by 6 hours after injection)

Weight-adjusted subcutaneous LMWH twice a day throughout the whole pregnancy (plasma level of anti-Xa 0.7-1.2 U/mL by 4-6 hours after injection). Concerns about the efficacy of subcutaneous UFH or LMWH in patients with mechanical valve prosthesis persist; the pros and cons of each regimen need to be discussed carefully.

Weight-adjusted subcutaneous LMWH twice a day throughout the whole pregnancy (plasma level of anti-Xa 0.7-1.2 U/mL by 4-6 hours after injection). Concerns about the efficacy of subcutaneous UFH or LMWH in patients with mechanical valve prosthesis persist; the pros and cons of each regimen need to be discussed carefully.

8. How should prosthetic valve thrombosis be treated?

Patients with thrombosis of a right-sided prosthetic valve should be considered for fibrinolytic therapy if there are no contraindications. The treatment for patients with left-sided valve thrombosis depends on the size of the thrombus. If the cross-sectional area is smaller than 0.8 cm2, fibrinolytic therapy is favored. For larger valve thrombosis, a surgical approach should be considered.

9. How does one prevent, diagnose, or treat prosthetic valve endocarditis?

Endocarditis on a prosthetic valve is a potentially catastrophic event that may require repeat surgery to cure the infection. Such infections usually originate on the prosthetic sewing ring and rapidly extend into perivalvular tissues. The risk of endocarditis is approximately the same for mechanical and biologic valve prostheses, although some studies have suggested slightly higher risks for biologic valves. The AHA published new prophylaxis guidelines in 2007 suggesting that patients with prosthetic heart valves should be considered for endocarditis prophylaxis for procedures likely to create bacteremia with an endocarditis-causing organisms. In the UK, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence Guidelines now do not recommend antibiotic prophylaxis before dental procedures for any patient.

10. How does one use echocardiography to follow patients after heart valve surgery?

11. What can cause recurrent symptoms when the prosthetic valve appears normal?

12. Should magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) be used after valve replacement?

According to a recent AHA scientific statement, the majority of prosthetic heart valves that have been tested have been labeled as MR safe; the remainder of heart valves and rings that have been tested have been labeled as MR conditional. On the basis of various studies and findings, the presence of a prosthetic heart valve that has been formally evaluated for MR safety should not be considered a contraindication to an MR examination at 3 Tesla or less (and possibly even 4.7 Tesla in some cases) any time after implantation. In cases where there is any doubt as to the safety of MRI scanning of a specific valve, the safety of the study should be discussed with an MRI specialist.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Ali, A., Halstead, J.C., Cafferty, F., et al. Are stentless valves superior to modern stented valves? A prospective randomized trial. Circulation. 2006;114:1535–1540.

2. Aurigemma G.P., Gaasch W.H.: Routine Management of Patients with Prosthetic Heart Valves. In Basow, DS, editor: UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013, UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-patients-with-prosthetic-heart-valves. Accessed March 26, 2013.

3. Bates, S.M., Greer, I.A., Hirsh, J., et al. Use of antithrombotic agents during pregnancy: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126:627S–644S.

4. Bonow, R.O., Carabello, B., Chatterjee, K., et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary. Circulation. 2006;114:e84–e231.

5. Douketis, J.D., et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e326S–e350S.

6. Edwards, M.B., Taylor, K.M., Shellock, F.G., et al. Prosthetic heart valves: evaluation of magnetic field interactions, heating, and artifacts at 1.5 T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:363–369.

7. Elkayam, U., Bitar, F. Valvular heart disease and pregnancy: part II: prosthetic valves. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:403–410.

8. Gott, V.L., Alejo, D.E., Cameron, D.E. Mechanical heart valves: 50 years of evolution. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:S2230–S2239.

9. Hammermeister, K., Sethi, G.K., Henderson, W.G., et al. Outcomes 15 years after valve replacement with a mechanical versus a bioprosthetic valve: final report of the Veterans Affairs randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1152–1158.

10. Kovacs, M.J., Kearon, C., Rodger, M., et al. Single-arm study of bridging therapy with low-molecular-weight heparin for patients at risk of arterial embolism who require temporary interruption of warfarin. Circulation. 2004;110:1658–1663.

11. Kulik, A., Be´dard, P., Lam, B.-K., et al. Mechanical versus bioprosthetic valve replacement in middle-aged patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:485–491.

12. Levine, G.N., Arai, A., Bleumke, D., et al. Safety of MRI/MRA in patients with cardiovascular devices; a scientific statement: statement by the AHA Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;116:2878–2921.

13. Mohty, D., Orszulak, T.A., Schaff, H.V., et al. Very long-term survival and durability of mitral valve repair for mitral valve prolapse. Circulation. 2001;104:I1–I7.

14. Stein, P.D., Alpert, J.S., Bussey, H.I., et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with mechanical and biological prosthetic heart valves. Chest. 2001;119:220S–227S.

15. Whitlock, R.P., et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for valvular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e576S–e600S.

16. Wilson, W., Taubert, K.A., Gewitz, M., et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:739–745. 747–60