Prolapse and disorders of the urinary tract

Uterovaginal prolapse

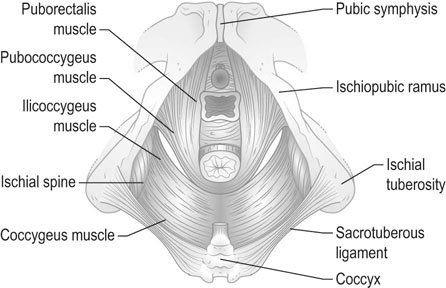

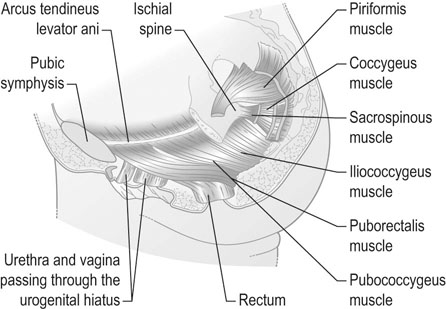

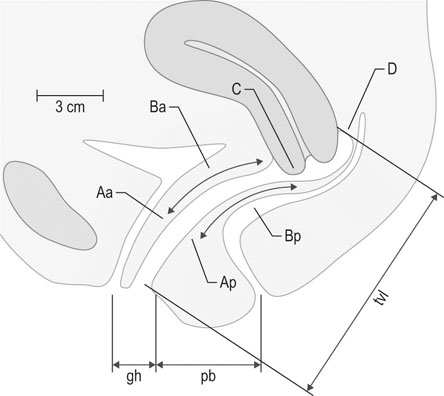

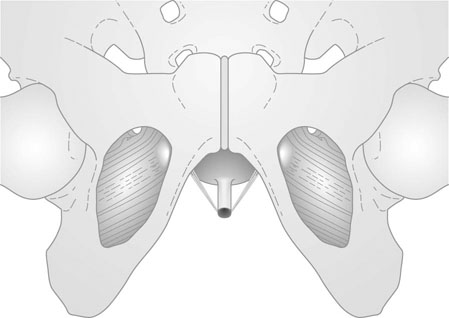

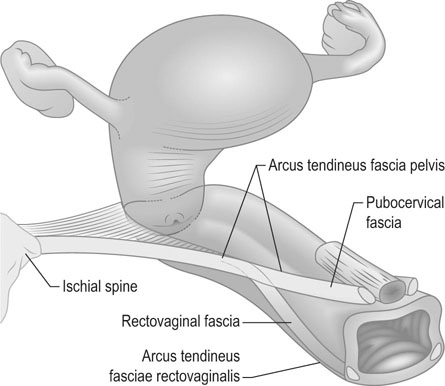

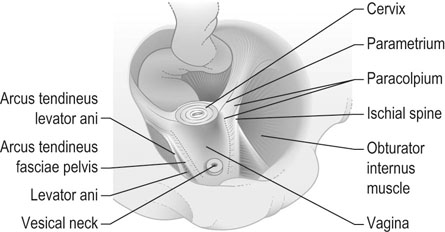

The position of the vagina and uterus depends on various fascial supports and ligaments derived from specific thickening of areas of the fascial support (Figs 21.1–21.4). There has been a paradigm shift in our understanding of the anatomy of pelvic floor supports and with it the pathophysiology of development of pelvic organ prolapse. There are three levels of pelvic organ support that are clinically relevant and conceptually easier to grasp. The uterosacral ligaments responsible for providing level I support to the upper vagina and the cervix (and by extension to the uterus) have a broad attachment over the second, third and fourth sacral vertebrae arising posteriorly from the junction of the cervix and the upper vagina running on each side lateral to the rectum towards the sacral attachments. The other important structure is the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis (ATFP; see Figs 21.3 and 21.5) also known as the ‘white line’ – a condensation of pelvic cellular tissue on the pelvic aspect of the obturator internus muscle. The ATFP runs from the ischial spines to the pubic tubercle and its terminal medial end is known as the iliopectineal ligament (Cooper’s ligament), well known to general surgeons that operate on inguinal and femoral hernias. Extending medially from the white lines are condensed sheets of pelvic cellular tissue suspending the anterior and posterior vaginal walls and the organs underlying these, namely the urinary bladder and the rectum providing level II support. The anterior support to the bladder was previously referred to as the pubovesicocervical fascia or ‘bladder pillars’, whereas the posterior support to the rectum was termed the rectovaginal fascia.

Definitions

Vaginal prolapse

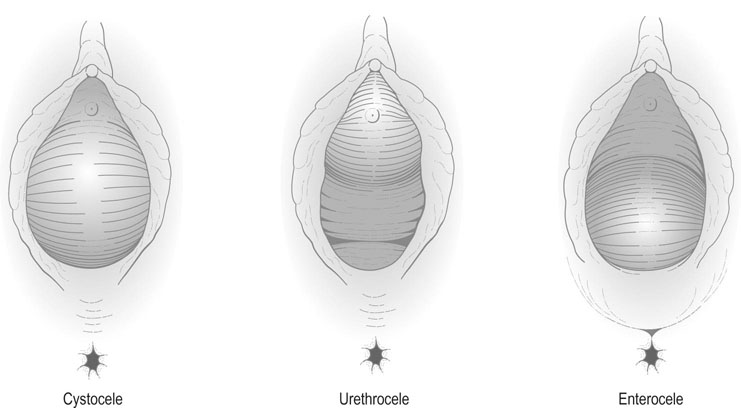

Prolapse of the anterior vaginal wall may affect the urethra (urethrocele), and the bladder (cystocele, Fig. 21.6). On examination, the urethra and bladder can be seen to descend and bulge into the anterior vaginal wall and, in severe cases, will be visible at or beyond the introitus of the vagina. An urethrocele is the result of damage to level III (anterior) support, i.e. the pubourethral ligaments. Cystoceles usually result due to a loss of level II support and usually due to a midline defect in pubovesicocervical fascia. A rectocele is formed by a combination of factors: a herniation of the rectum through a defect in the rectovaginal fascia as well as a lateral detachment of the level II support from the ATFP. This can usually be seen as a visible bulge of the rectum through the posterior vaginal wall. It is often associated with a deficiency and laxity of the perineum. This is the classical level III defect (posterior) affecting the perineal body.

An enterocele is formed by a prolapse of the small bowel through the rectouterine pouch, i.e. the pouch of Douglas, through the upper part of the vaginal vault (Fig. 21.6). The condition may occur in isolation, but usually occurs in association with uterine prolapse. An enterocele may also occur following hysterectomy when there is inadequate support of the vaginal vault. This represents damage to level I support.

Uterine prolapse

Descent of the uterus, which occurs when level I support is deficient, may occur in isolation from vaginal wall prolapse but more commonly occurs in conjunction with it. First-degree prolapse of the uterus often occurs in association with retroversion of the uterus and descent of the cervix within the vagina. If the cervix descends to the vaginal introitus, the prolapse is defined as second degree. The term procidentia is applied to where the cervix and the body of the uterus and the vagina walls protrude through the introitus. The word actually means ‘prolapse’ or ‘falling’ but is generally reserved for the description of total or third-degree prolapse (Fig. 21.7).

Symptoms and signs

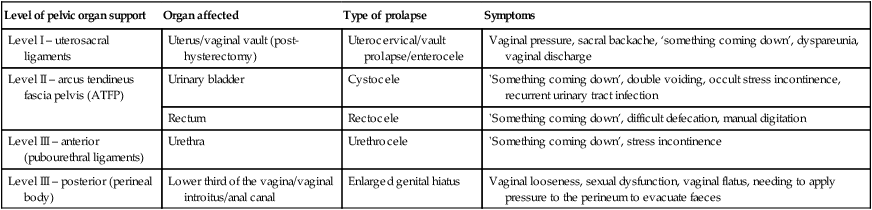

Symptoms generally depend on the severity and site of the prolapse (Table 21.1).

Table 21.1

Levels of supports, with diagnosis and co-relation with symptoms

| Level of pelvic organ support | Organ affected | Type of prolapse | Symptoms |

| Level I – uterosacral ligaments | Uterus/vaginal vault (post-hysterectomy) | Uterocervical/vault prolapse/enterocele | Vaginal pressure, sacral backache, ‘something coming down’, dyspareunia, vaginal discharge |

| Level II – arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (ATFP) | Urinary bladder | Cystocele | ‘Something coming down’, double voiding, occult stress incontinence, recurrent urinary tract infection |

| Rectum | Rectocele | ‘Something coming down’, difficult defecation, manual digitation | |

| Level III – anterior (pubourethral ligaments) | Urethra | Urethrocele | ‘Something coming down’, stress incontinence |

| Level III – posterior (perineal body) | Lower third of the vagina/vaginal introitus/anal canal | Enlarged genital hiatus | Vaginal looseness, sexual dysfunction, vaginal flatus, needing to apply pressure to the perineum to evacuate faeces |

There are some symptoms that are common to all forms of prolapse; these include:

• A sense of fullness in the vagina associated with dragging discomfort.

Staging/grading of prolapse

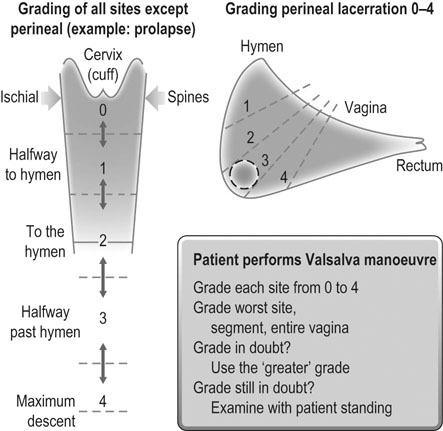

Baden–Walker halfway system (Fig. 21.8 and Table 21.2)

This system was developed in an effort to introduce more objectivity into the quantification of pelvic organ prolapse. For example, measurements in centimetres are used instead of subjective grades. Nine specific measurements are recorded as indicated in Figure 21.9.

Table 21.2

Primary and secondary symptoms at each site used in the Baden–Walker halfway system

| Anatomic site | Primary symptoms | Secondary symptoms |

| Urethral | Urinary incontinence | Falling out |

| Vesical | Voiding difficulties | Falling out |

| Uterine | Falling out, heaviness, etc. | |

| Cul-de-sac | Pelvic pressure (standing) | Falling out |

| Rectal | True bowel pocket | Falling out |

| Perineal | Anal incontinence | Too loose (gas/faeces) |

(Reproduced with permission from Baden WF, Walker T (1992) Surgical repair of vaginal defects. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, p. 12.)

Pathogenesis

• Congenital: Uterine prolapse in young or nulliparous women is due to weakness of the supports of the uterus and vaginal vault. There is a minimal degree of vaginal wall prolapse.

• Acquired: The commonest form of prolapse is acquired under the influence of multiple factors. This type of prolapse is both uterine and vaginal but it must also be remembered that vaginal wall prolapse can also occur without any uterine descent. Predisposing factors include:

High parity: Uterovaginal prolapse is a condition of parous women. The pelvic floor provides direct and indirect support for the vaginal walls and when this support is disrupted by laceration or over distension it predisposes to vaginal wall prolapse. Instrumental delivery employing forceps/ventouse especially mid-cavity rotational forceps delivery may play a contributory role in the causation of urinary incontinence and prolapse in later life.

High parity: Uterovaginal prolapse is a condition of parous women. The pelvic floor provides direct and indirect support for the vaginal walls and when this support is disrupted by laceration or over distension it predisposes to vaginal wall prolapse. Instrumental delivery employing forceps/ventouse especially mid-cavity rotational forceps delivery may play a contributory role in the causation of urinary incontinence and prolapse in later life.

Raised intra-abdominal pressure: Tumours or ascites may result in raised intra-abdominal pressure, but a more common cause is a chronic cough and chronic constipation.

Raised intra-abdominal pressure: Tumours or ascites may result in raised intra-abdominal pressure, but a more common cause is a chronic cough and chronic constipation.

Hormonal changes: The symptoms of prolapse often worsen rapidly at the time of the menopause. Cessation of oestrogen production leads to thinning of the vaginal walls and the supports of the uterus. Although the prolapse is generally present before the menopause, it is at this time that the symptoms become noticeable and the degree of descent visibly worsens. The age at first vaginal childbirth affects the incidence of prolapse and urinary incontinence in later life. It has been postulated that increased maternal age predisposes to levator trauma making these women more prone to developing pelvic floor disorders.

Hormonal changes: The symptoms of prolapse often worsen rapidly at the time of the menopause. Cessation of oestrogen production leads to thinning of the vaginal walls and the supports of the uterus. Although the prolapse is generally present before the menopause, it is at this time that the symptoms become noticeable and the degree of descent visibly worsens. The age at first vaginal childbirth affects the incidence of prolapse and urinary incontinence in later life. It has been postulated that increased maternal age predisposes to levator trauma making these women more prone to developing pelvic floor disorders.

Management

The management of prolapse can be conservative or surgical.

Conservative treatment

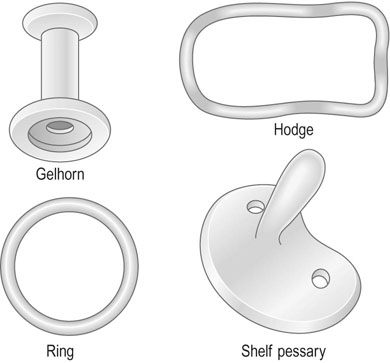

The most widely used pessaries (Fig. 21.10) are:

• Ring pessary: This pessary consists of a malleable plastic ring, which may vary in diameter from 60–105 mm. The pessary is inserted in the posterior fornix and behind the pubic symphysis. Distension of the vaginal walls tends to support the vaginal wall prolapse.

• Hodge pessary: This is a rigid, elongated, curved ovoid which is inserted in a similar way to the ring pessary and is principally useful in uterine retroversion.

• Gelhorn pessary: This pessary is shaped like a collar stud and is used in the treatment of severe degrees of prolapse.

• Shelf pessary: This is shaped like a coat hook and is used mainly in the treatment of uterine or vaginal vault prolapse.

The main problem with long-term use of pessaries is ulceration of the vaginal vault and rarely a fistula may form, usually between the bladder and the vagina, if the pessary is ‘neglected’ or ‘forgotten’. Pessaries should be replaced every 4–6 months and the vagina should be examined for any signs of ulceration. In postmenopausal women it is considered good practice to prescribe vaginal oestrogen creams/tablets to prevent ulceration.

Surgical treatment

Fascial repairs

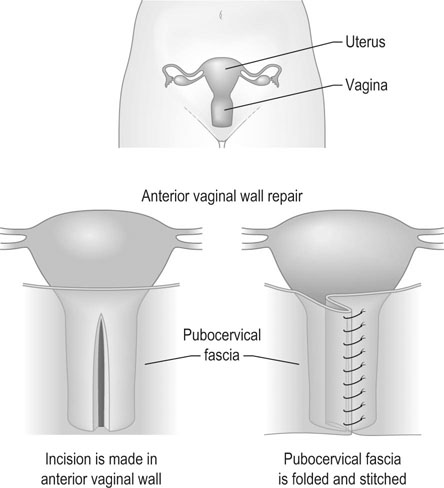

Classically surgical treatment of a cystocele is by anterior colporrhaphy (Fig. 21.11). The operation consists of dissection of the prolapsed viscus (the urinary bladder) off the vaginal flaps, buttressing the pubovesicocervical fascia with durable delayed absorbable sutures and closure of the vaginal skin. Current practice does not include excision of ‘excess vaginal skin’ as the vagina is expected to remodel and the perceived laxity all but disappears in 6–8 weeks’ time.

Graft repairs

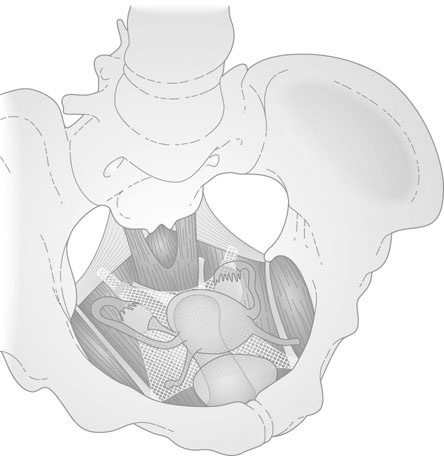

The earliest repairs using mesh have been to treat vault prolapse (Fig 21.12). The prolapsed vaginal vault is treated by suspending the vaginal vault from the anterior longitudinal ligament of the sacrum using a synthetic mesh. This procedure is known as sacrocolpopexy – a procedure that can be performed laparoscopically or through a laparotomy. More recently ‘needle driven mesh kits’ have become available to treat vaginal prolapse. The first of these kits was called the PERIGEE™ used to suspend the prolapsed bladder from one ATFP to its opposite member thus recreating the hammock like arrangement that existed in the pelvis prior to the occurrence of the prolapse. A similar device called the APOGEE™ is available to treat large enteroceles and vault prolapses. More recently newer versions called the Anterior and Posterior Elevate™ have been developed to treat anterior, middle and posterior compartment disorders that are safer to use and employ mesh that is more bio-compatible. These new devices require specialized instruction and training prior to use.

Urinary tract disorders

Structure and physiology of the urinary tract

Common disorders of bladder function

The common symptoms of bladder dysfunction include:

Incontinence of urine

• True incontinence is continuous loss of urine through the vagina; it is commonly associated with fistula formation but may occasionally be a manifestation of urinary retention with overflow.

• Stress incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine that occurs during a brief period of raised intra-abdominal pressure. It is usually related to injury to the continence mechanism described above and lack of estrogenic stimulation and usually manifests around menopause. Examination reveals the involuntary loss of urine during coughing usually accompanied by a hypermobility of the urethra and a descent of the anterior vaginal wall.

• Urge incontinence is the problem of sudden detrusor contraction, with uncontrolled loss of urine. The condition may be due to idiopathic detrusor instability or associated with urinary infection, obstructive uropathy, diabetes or neurological disease. It is particularly important to exclude urinary tract infection.

• Mixed urge and stress incontinence occurs in a substantial number of women. Women with urge incontinence also have true stress incontinence and it is particularly important to treat the detrusor instability prior to correcting stress incontinence. Failure to do so may lead to a worsening of the condition.

• Overflow incontinence occurs when the bladder becomes dilated or flaccid with minimal or no tone/function. It is not uncommon after vaginal delivery or when the bladder is ‘neglected’ after a spinal anaesthetic. A bladder scan usually reveals the presence of a residual of more than half the bladder capacity. The bladder then becomes ‘lazy’ and empties when it becomes full.

• Miscellaneous types of incontinence include infections, medications, prolonged immobilization, cognitive impairment and in certain situations may precipitate incontinence.

Urinary retention

Acute urinary retention is less of a problem in women. It can however be seen:

• after vaginal delivery and episiotomy

• following operative delivery

• after vaginal repair procedures, particularly those operations that involve posterior vaginal wall and perineum.

• in the menopause – spontaneous obstructive uropathy is more likely to occur in menopausal women

• in pregnancy – a retroverted uterus may become impacted in the pelvis towards the end of the first trimester

• when inflammatory lesions of the vulva are present

• as a result of untreated over-distension of the bladder (such as following delivery), neuropathy or malignancy.

Diagnosis

There are other types of fistula with communications between bowel and urinary tract and between bowel and vagina, but these are less common.

Urinary fistulas are localized by:

• instillation of methylene blue via a catheter into the bladder; the appearance of dye in the vagina indicates a vesicovaginal fistula.

The differential diagnosis between stress and urge incontinence is more difficult and is often unsatisfactory. Adequate preoperative assessment is important if the correct operation is to be employed or if surgery is to be avoided. It is important to assess patients with a validated patient questionnaire (the Modified Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Questionnaire is a good example) with a 3-day urinary diary and a pad test. These help the clinician gain an insight into how the symptoms of urinary incontinence affect the patient on a day-to-day basis. The bladder and urethra are assessed in the laboratory by urodynamics. This procedure usually involves three basic steps:

1. Uroflowmetry: The patient is asked to pass urine into a specially designed toilet that measures voided volume, maximal and average urinary flow rates. Flow rates of >15 mL/sec are considered acceptable and it is expected that a normal bladder will completely empty itself. Flow rates of <15 mL/sec are indicative of voiding dysfunction and in the female often indicate a ‘functional obstruction’ rather than an anatomic one. Occasionally a powerful detrusor may cause the bladder to contract against a closed internal urethral meatus resulting in dysfunctional voiding, a condition termed ‘detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia’.

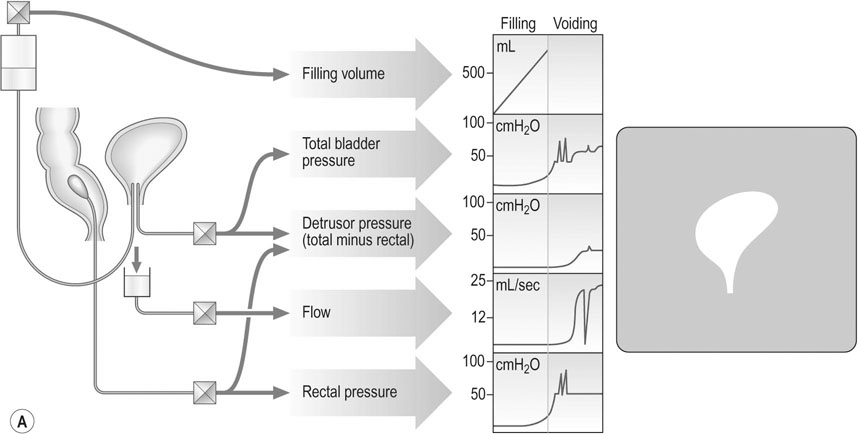

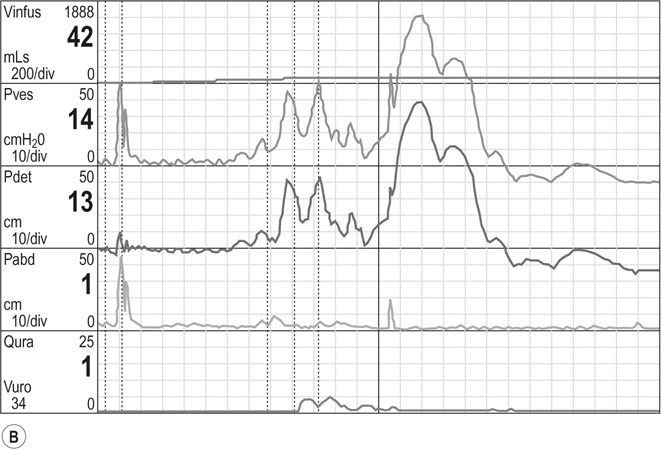

2. The cystometrogram (Fig 21.13): Pressure is measured intravesically and intravaginally or less commonly intrarectally, because intravaginal pressure represents intra-abdominal pressure and is subtracted from the intravesical pressure to give a measure of detrusor pressure. The volume of fluid in the bladder at which the first desire to void occurs is usually about 150 mL. A strong desire to void occurs at 400 mL in the normal bladder. High detrusor pressure at a lower volume reflects an abnormally sensitive bladder associated with chronic infection. There should be no detrusor contraction during filling, and any contraction that occurs under these circumstances indicates detrusor instability. An underactive detrusor shows no contraction on complete filling and indicates an abnormality of neurological control. The average bladder has a capacity of 250–550 mL, but capacity is a poor index of bladder function. Thus, cystometry is a useful method for assessing detrusor muscle function or detrusor instability, which may result in urge incontinence.

3. Urethral pressure profile: This is performed at the very end of the cystometry and measures the pressure within the mid-urethra, in particular the maximum urethral closure pressure (MUCP). This is of value in predicting the likelihood of surgical success after an anti-incontinence procedure. Pressures <20 cm of H2O are predictive of poorer outcomes.

In some units an endoscopic view of the bladder called ‘cystoscopy’ and an ultrasound scan of the pelvic floor are the additional procedures performed in the evaluation of the incontinent woman.

Management

Urinary tract fistula

Stress incontinence

The following procedures are commonly used:

• Mid-urethral slings (Fig. 21.14)

Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT™): Bladder neck elevation can be achieved by the placement of a tension-free vaginal tape. A polypropylene tape is inserted through a sub-urethral vaginal incision and guided via a needle paravesically to exit from the symphysis pubis. This can be carried out under local, regional or general anaesthetic and the tape is placed mid-urethrally in a tension-free manner. A cystourethroscopy is performed intra-operatively to rule out damage to the bladder and urethra. As this procedure is minimally invasive most women are able to return to normal activity within 1–2 weeks. The long-term success rates are around 80%.

Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT™): Bladder neck elevation can be achieved by the placement of a tension-free vaginal tape. A polypropylene tape is inserted through a sub-urethral vaginal incision and guided via a needle paravesically to exit from the symphysis pubis. This can be carried out under local, regional or general anaesthetic and the tape is placed mid-urethrally in a tension-free manner. A cystourethroscopy is performed intra-operatively to rule out damage to the bladder and urethra. As this procedure is minimally invasive most women are able to return to normal activity within 1–2 weeks. The long-term success rates are around 80%.

• Miscellaneous procedures still in vogue

Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension involves bladder neck elevation by suturing the upper lateral vaginal walls to the iliopectineal ligaments under laparoscopic control. The success rates are around 60% and the procedure results in voiding dysfunction in a significant majority of patients. This procedure has more or less been invalidated by the more popular and safer mid-urethral slings.

Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension involves bladder neck elevation by suturing the upper lateral vaginal walls to the iliopectineal ligaments under laparoscopic control. The success rates are around 60% and the procedure results in voiding dysfunction in a significant majority of patients. This procedure has more or less been invalidated by the more popular and safer mid-urethral slings.

Transurethral injections: Injectable bulking agents can be injected via a cystoscope into the mid-urethra. These are simple procedures with very little perioperative morbidity and have success rates of about 40–60%. These are useful adjuncts to the mid-urethral slings especially in recurrences and in women with multiple failed operations. The commonest agents employed are collagen (glutaraldehyde cross-linked bovine collagen), silicon (macroparticulate silicon particles), Durasphere® (pyrolytic carbon-coated beads), etc.

Transurethral injections: Injectable bulking agents can be injected via a cystoscope into the mid-urethra. These are simple procedures with very little perioperative morbidity and have success rates of about 40–60%. These are useful adjuncts to the mid-urethral slings especially in recurrences and in women with multiple failed operations. The commonest agents employed are collagen (glutaraldehyde cross-linked bovine collagen), silicon (macroparticulate silicon particles), Durasphere® (pyrolytic carbon-coated beads), etc.

The unstable bladder: overactive bladder syndrome (OAB)

Drug treatment

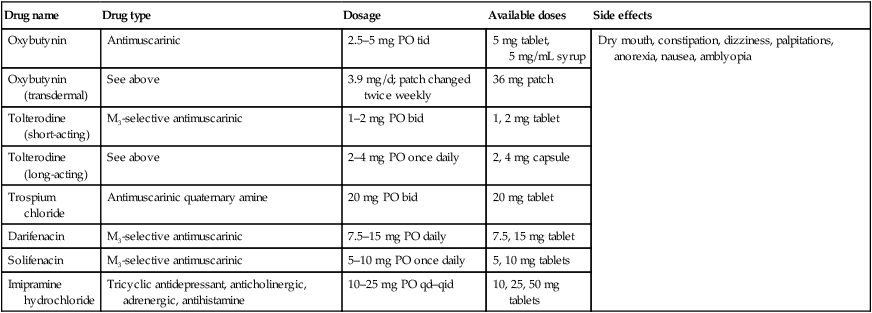

The alternative approach is to use anticholinergic drugs that act at the level of the bladder wall. These act on the muscarinic receptors on the bladder wall and cause relaxation. Some of these drugs are more specific and act on M3 receptors. The more specific the drug the less likely it is to cause side-effects. The drugs listed in Table 21.3 are in increasing order of specificity and better side-effect profile.

Table 21.3

Drug therapy of overactive bladder

| Drug name | Drug type | Dosage | Available doses | Side effects |

| Oxybutynin | Antimuscarinic | 2.5–5 mg PO tid | 5 mg tablet, 5 mg/mL syrup | Dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, palpitations, anorexia, nausea, amblyopia |

| Oxybutynin (transdermal) | See above | 3.9 mg/d; patch changed twice weekly | 36 mg patch | |

| Tolterodine (short-acting) | M3-selective antimuscarinic | 1–2 mg PO bid | 1, 2 mg tablet | |

| Tolterodine (long-acting) | See above | 2–4 mg PO once daily | 2, 4 mg capsule | |

| Trospium chloride | Antimuscarinic quaternary amine | 20 mg PO bid | 20 mg tablet | |

| Darifenacin | M3-selective antimuscarinic | 7.5–15 mg PO daily | 7.5, 15 mg tablet | |

| Solifenacin | M3-selective antimuscarinic | 5–10 mg PO once daily | 5, 10 mg tablets | |

| Imipramine hydrochloride | Tricyclic antidepressant, anticholinergic, adrenergic, antihistamine | 10–25 mg PO qd–qid | 10, 25, 50 mg tablets |