Chapter 14 Progressive Preoperative Pneumoperitoneum for Hernias with Loss of Abdominal Domain ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy

1 Features/Characteristics of the Defect

Definition of Loss of Abdominal Domain

Definition of Loss of Abdominal Domain

There is no consensus in the literature on the definition of loss of abdominal domain. Determination of this condition is subjective and typically refers to massive hernias with a significant amount of intestinal contents that have herniated through the abdominal wall into a hernia sac that forms a secondary abdominal cavity. On physical exam, the inability to reduce the herniated contents below the level of the fascia when the patient is lying supine should raise suspicion of the diagnosis. Although the surgeon can often make the assumption that a patient has loss of domain on physical exam, we utilize computed tomography (CT) to determine the true nature of the hernia.

There is no consensus in the literature on the definition of loss of abdominal domain. Determination of this condition is subjective and typically refers to massive hernias with a significant amount of intestinal contents that have herniated through the abdominal wall into a hernia sac that forms a secondary abdominal cavity. On physical exam, the inability to reduce the herniated contents below the level of the fascia when the patient is lying supine should raise suspicion of the diagnosis. Although the surgeon can often make the assumption that a patient has loss of domain on physical exam, we utilize computed tomography (CT) to determine the true nature of the hernia.2 Measuring Loss of Domain

We define a loss of abdominal domain on CT scan as greater than 50% of the intestinal contents lying outside the native abdominal cavity in the hernia sac. This may be more accurately defined when the ratio of the volume of the hernia sac to the volume of the abdominal cavity is ≥0.5.

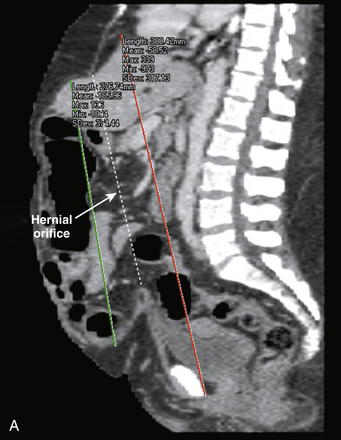

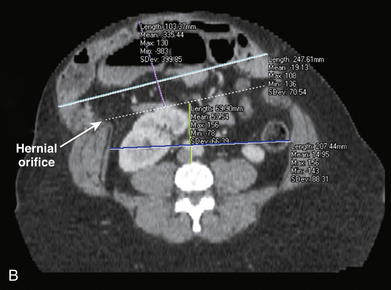

We define a loss of abdominal domain on CT scan as greater than 50% of the intestinal contents lying outside the native abdominal cavity in the hernia sac. This may be more accurately defined when the ratio of the volume of the hernia sac to the volume of the abdominal cavity is ≥0.5. A sagittal reconstruction of the CT scan is used to measure the length of the hernia sac from the top to the bottom of the sac. The length of the abdominal cavity is measured from the top of the diaphragm to the inferior aspect of the symphysis pubis (Fig. 14-1, A).

A sagittal reconstruction of the CT scan is used to measure the length of the hernia sac from the top to the bottom of the sac. The length of the abdominal cavity is measured from the top of the diaphragm to the inferior aspect of the symphysis pubis (Fig. 14-1, A). Axial reconstructions are used to measure the width of the hernia sac and abdominal cavity at their widest point. The height of the hernia sac is measured from an imaginary line drawn across the hernial orifice to the apex of the hernia sac at its tallest portion. The height of the abdominal cavity is measured from the anterior portion of the fourth lumbar space to an imaginary line drawn across the hernial orifice (see Fig. 14-1, B).

Axial reconstructions are used to measure the width of the hernia sac and abdominal cavity at their widest point. The height of the hernia sac is measured from an imaginary line drawn across the hernial orifice to the apex of the hernia sac at its tallest portion. The height of the abdominal cavity is measured from the anterior portion of the fourth lumbar space to an imaginary line drawn across the hernial orifice (see Fig. 14-1, B). Using the formula to measure the volume of an ellipsoid (V = 4/3 × π × r1 × r2 × r3), the hernia sac and abdominal cavity volumes can be measured and compared. To simplify the ellipsoid volume equation, multiply the length, height, and width measurements of the cavities times a factor of 0.52 (V = 0.52 × L × H × W). Loss of domain exists when the ratio of the volume of the hernia sac to the volume of the abdominal cavity is ≥0.5.

Using the formula to measure the volume of an ellipsoid (V = 4/3 × π × r1 × r2 × r3), the hernia sac and abdominal cavity volumes can be measured and compared. To simplify the ellipsoid volume equation, multiply the length, height, and width measurements of the cavities times a factor of 0.52 (V = 0.52 × L × H × W). Loss of domain exists when the ratio of the volume of the hernia sac to the volume of the abdominal cavity is ≥0.5. Physiology of Hernias with Loss of Abdominal Domain

Physiology of Hernias with Loss of Abdominal Domain

In patients with loss of abdominal domain, the bowels reside outside the abdominal cavity. As intraabdominal pressure decreases to approach atmospheric pressure, abdominal viscera become edematous and their vasculature becomes engorged. This makes simple hernia reduction nearly impossible. In addition, respiratory function is altered secondary to the loss of diaphragmatic support, and anterior spinal support fails, leading to lordosis.

In patients with loss of abdominal domain, the bowels reside outside the abdominal cavity. As intraabdominal pressure decreases to approach atmospheric pressure, abdominal viscera become edematous and their vasculature becomes engorged. This makes simple hernia reduction nearly impossible. In addition, respiratory function is altered secondary to the loss of diaphragmatic support, and anterior spinal support fails, leading to lordosis.4 Physiology of Progressive Preoperative Pneumoperitoneum

The immediate reintroduction of viscera and abdominal reconstruction in patients with loss of domain can result in a significant increase in intraabdominal pressure, which can lead to abdominal compartment syndrome and its resultant ill effects. Progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum (PPP) attenuates the adverse physiologic effects associated with ventral hernia repair in patients with a loss of abdominal domain.

The immediate reintroduction of viscera and abdominal reconstruction in patients with loss of domain can result in a significant increase in intraabdominal pressure, which can lead to abdominal compartment syndrome and its resultant ill effects. Progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum (PPP) attenuates the adverse physiologic effects associated with ventral hernia repair in patients with a loss of abdominal domain. Insufflation of the abdominal cavity acts as an intraperitoneal pneumatic tissue expander and lengthens the abdominal wall musculature, increasing the volume of the abdominal cavity. This allows for adequate accommodation for the herniated contents.

Insufflation of the abdominal cavity acts as an intraperitoneal pneumatic tissue expander and lengthens the abdominal wall musculature, increasing the volume of the abdominal cavity. This allows for adequate accommodation for the herniated contents. The pneumoperitoneum also dissects throughout the intraperitoneal cavity providing a pneumatic lysis of adhesions aided by gravity as the bowels are suspended by their adhesions within the hernia sac.

The pneumoperitoneum also dissects throughout the intraperitoneal cavity providing a pneumatic lysis of adhesions aided by gravity as the bowels are suspended by their adhesions within the hernia sac. Physiologically, PPP slowly creates a chronic abdominal compartment syndrome. With decreased diaphragmatic excursion, the patient is forced to overcome the inherent decreased inspiratory capacity. Additionally the adverse cardiovascular effects of acute abdominal compartment syndrome are attenuated by the slow introduction of intraperitoneal air.

Physiologically, PPP slowly creates a chronic abdominal compartment syndrome. With decreased diaphragmatic excursion, the patient is forced to overcome the inherent decreased inspiratory capacity. Additionally the adverse cardiovascular effects of acute abdominal compartment syndrome are attenuated by the slow introduction of intraperitoneal air.2 Preoperative Considerations

1 Physical Examination

The physical exam alone is often helpful in determining whether a patient has loss of domain. With the patient lying supine on the examination table, the surgeon should attempt to reduce the herniated contents below the fascia. If the hernia does not reduce because of the amount of herniated contents, the patient likely has loss of domain

The physical exam alone is often helpful in determining whether a patient has loss of domain. With the patient lying supine on the examination table, the surgeon should attempt to reduce the herniated contents below the fascia. If the hernia does not reduce because of the amount of herniated contents, the patient likely has loss of domain The abdominal wall should be examined for elasticity. Although some massive hernias may be irreducible, the patient’s abdominal wall musculature may have such laxity and elasticity that it could accommodate the herniated contents easily at the time of surgery. This finding would obviate the need for PPP because single stage repair may be feasible.

The abdominal wall should be examined for elasticity. Although some massive hernias may be irreducible, the patient’s abdominal wall musculature may have such laxity and elasticity that it could accommodate the herniated contents easily at the time of surgery. This finding would obviate the need for PPP because single stage repair may be feasible. The quality of the skin should be examined to determine if any adjunctive maneuvers will be required to obtain safe skin closure at the time of hernia repair.

The quality of the skin should be examined to determine if any adjunctive maneuvers will be required to obtain safe skin closure at the time of hernia repair. Wide thin scars, ulcerated skin, thin subcutaneous tissue with tense and immobile skin, and large pannus flaps should all raise concern over skin closure. Consultation with a plastic surgeon may help determine the need for preoperative tissue expanders, panniculectomy, or complex skin closure at the time of hernia repair.

Wide thin scars, ulcerated skin, thin subcutaneous tissue with tense and immobile skin, and large pannus flaps should all raise concern over skin closure. Consultation with a plastic surgeon may help determine the need for preoperative tissue expanders, panniculectomy, or complex skin closure at the time of hernia repair.2 Computed Axial Tomography

As previously described, the volume of the hernia sac and abdominal cavity are calculated and compared. A volume ratio of the hernia sac to the abdominal cavity of ≥0.5 should raise the suspicion of loss of abdominal domain.

As previously described, the volume of the hernia sac and abdominal cavity are calculated and compared. A volume ratio of the hernia sac to the abdominal cavity of ≥0.5 should raise the suspicion of loss of abdominal domain. Other attributes of the abdominal wall should be examined on CT because they may determine the utility or futility of preoperative pneumoperitoneum.

Other attributes of the abdominal wall should be examined on CT because they may determine the utility or futility of preoperative pneumoperitoneum. In our experience, patients with small defects and a significant amount of herniated contents benefit the most from preoperative pneumoperitoneum.

In our experience, patients with small defects and a significant amount of herniated contents benefit the most from preoperative pneumoperitoneum. Patients with round-shaped abdominal cavities and thick, robust rectus abdominis and oblique muscles may experience less muscle lengthening with preoperative pneumoperitoneum compared to those with a more ellipsoid appearance to the abdominal wall and thin atrophic musculature.

Patients with round-shaped abdominal cavities and thick, robust rectus abdominis and oblique muscles may experience less muscle lengthening with preoperative pneumoperitoneum compared to those with a more ellipsoid appearance to the abdominal wall and thin atrophic musculature. Patients with “open book” abdomens, such as those with significant loss of abdominal wall substance (missing abdominal wall musculature) and hernia defects that span the entire abdominal wall, may not benefit anatomically from preoperative pneumoperitoneum because there may not be enough abdominal wall musculature to stretch. The physiologic benefits may still be realized however.

Patients with “open book” abdomens, such as those with significant loss of abdominal wall substance (missing abdominal wall musculature) and hernia defects that span the entire abdominal wall, may not benefit anatomically from preoperative pneumoperitoneum because there may not be enough abdominal wall musculature to stretch. The physiologic benefits may still be realized however.3 Planning Abdominal Wall Reconstruction

Weight Loss

Weight Loss

Most patients with massive hernias and loss of domain are obese. Every effort should be made to have the patient lose weight preoperatively.

Most patients with massive hernias and loss of domain are obese. Every effort should be made to have the patient lose weight preoperatively. Contaminated Abdominal Wall

Contaminated Abdominal Wall

Patients with enteral or urinary stomas or enterocutaneous fistulas are candidates for PPP. Attention should be paid to the stoma to ensure ischemia does not develop during insufflation.

Patients with enteral or urinary stomas or enterocutaneous fistulas are candidates for PPP. Attention should be paid to the stoma to ensure ischemia does not develop during insufflation. Patients with infected mesh and massive hernia with loss of domain pose a special problem. Although still candidates for preoperative pneumoperitoneum, serious consideration should be given to mesh removal and skin closure first followed by PPP at a second stage. An abdominal wall with infected mesh will be indurated and edematous; as a result, little muscle lengthening will occur with PPP. Additionally, mesh removal will undoubtedly damage some abdominal wall, making the immediate reconstruction all the more difficult.

Patients with infected mesh and massive hernia with loss of domain pose a special problem. Although still candidates for preoperative pneumoperitoneum, serious consideration should be given to mesh removal and skin closure first followed by PPP at a second stage. An abdominal wall with infected mesh will be indurated and edematous; as a result, little muscle lengthening will occur with PPP. Additionally, mesh removal will undoubtedly damage some abdominal wall, making the immediate reconstruction all the more difficult.3 Operative Steps

1 Stage I

Placement of Percutaneous Vena Cava Filter

Placement of Percutaneous Vena Cava Filter

PPP significantly elevates the intraabdominal pressure and creates a chronic abdominal compartment syndrome. As a result, venous return through the vena cava is decreased, and patients are at risk for thromboembolic events.

PPP significantly elevates the intraabdominal pressure and creates a chronic abdominal compartment syndrome. As a result, venous return through the vena cava is decreased, and patients are at risk for thromboembolic events. Exploratory Laparoscopy with Placement of Percutaneous Catheter System

Exploratory Laparoscopy with Placement of Percutaneous Catheter System

Exploratory laparoscopy allows for minimally invasive access to the abdominal cavity for direct visualization and placement of a percutaneously placed intraperitoneal catheter system for the pneumoperitoneum.

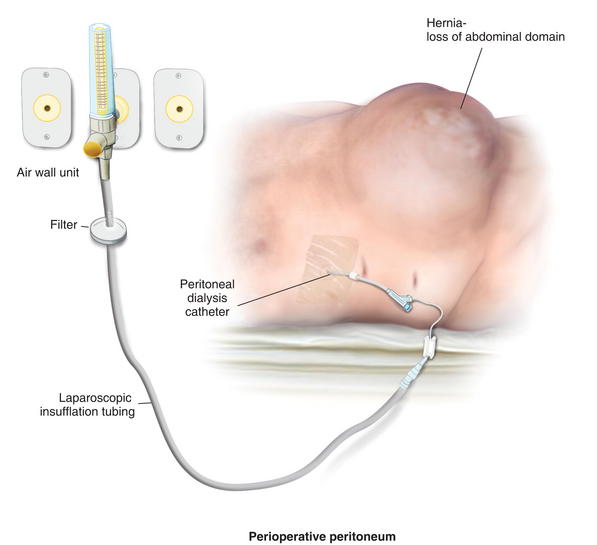

Exploratory laparoscopy allows for minimally invasive access to the abdominal cavity for direct visualization and placement of a percutaneously placed intraperitoneal catheter system for the pneumoperitoneum. A peritoneal dialysis catheter is placed under direct vision, using the Seldinger technique with a percutaneous, tear-away introducer sheath (Fig. 14-3).

A peritoneal dialysis catheter is placed under direct vision, using the Seldinger technique with a percutaneous, tear-away introducer sheath (Fig. 14-3). The catheter cuff is placed into the subcutaneous tissue and the catheter is sutured in position (Fig. 14-4).

The catheter cuff is placed into the subcutaneous tissue and the catheter is sutured in position (Fig. 14-4).2 Stage II

Progressive Preoperative Pneumoperitoneum

Progressive Preoperative Pneumoperitoneum

Laparoscopic insufflation tubing is utilized to connect the air hose at the patient’s bedside to the peritoneal dialysis catheter (Fig. 14-5).

Laparoscopic insufflation tubing is utilized to connect the air hose at the patient’s bedside to the peritoneal dialysis catheter (Fig. 14-5). The air is turned on slowly to begin insufflation. The patient is closely monitored for signs of distress.

The air is turned on slowly to begin insufflation. The patient is closely monitored for signs of distress. The insufflation proceeds and the patient will begin to complain of abdominal tightness followed by mild flank discomfort. Once the patient begins to experience some shortness of breath or mild anxiety, the insufflation is stopped. There is no specific volume of air that should be injected nor the intraperitoneal pressure measured. The endpoint of insufflation is always the patient’s level of discomfort.

The insufflation proceeds and the patient will begin to complain of abdominal tightness followed by mild flank discomfort. Once the patient begins to experience some shortness of breath or mild anxiety, the insufflation is stopped. There is no specific volume of air that should be injected nor the intraperitoneal pressure measured. The endpoint of insufflation is always the patient’s level of discomfort. Repeat CT Scan to Determine Suitability for Stage III

Repeat CT Scan to Determine Suitability for Stage III

After 7 days of daily PPP, a CT scan is performed to determine the suitability of the abdominal wall for repair.

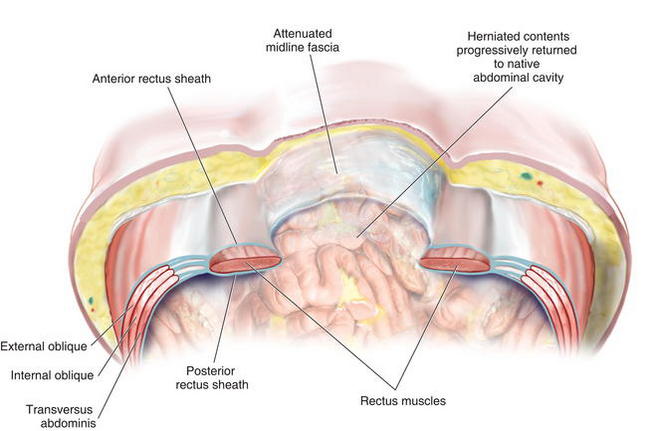

After 7 days of daily PPP, a CT scan is performed to determine the suitability of the abdominal wall for repair. The CT should demonstrate that the herniated contents have fallen back into the native abdominal cavity and now lie below an imaginary line drawn across the hernial orifice (Figs. 14-6 to 14-9).

The CT should demonstrate that the herniated contents have fallen back into the native abdominal cavity and now lie below an imaginary line drawn across the hernial orifice (Figs. 14-6 to 14-9). If the bowel has not fallen back into the abdominal cavity and the volume of the abdomen does not look to have increased significantly, then pneumoperitoneum should continue for 4-5 more days and a repeat CT performed. If at this point there is no change, it is unlikely PPP will work as a pneumatic tissue expander and consideration should be given to either saline tissue expansion or myofascial pedicled flap closure of the abdominal wall.

If the bowel has not fallen back into the abdominal cavity and the volume of the abdomen does not look to have increased significantly, then pneumoperitoneum should continue for 4-5 more days and a repeat CT performed. If at this point there is no change, it is unlikely PPP will work as a pneumatic tissue expander and consideration should be given to either saline tissue expansion or myofascial pedicled flap closure of the abdominal wall.3 Stage III

Abdominal Wall Reconstruction

Abdominal Wall Reconstruction

Once the patient is ready for reconstruction, the surgeon should use the technique with which he or she is most comfortable.

Once the patient is ready for reconstruction, the surgeon should use the technique with which he or she is most comfortable. Rives-Stoppa with PCST

Rives-Stoppa with PCST

After a complete lysis of adhesions a towel is placed intraperitoneally to protect the underlying viscera.

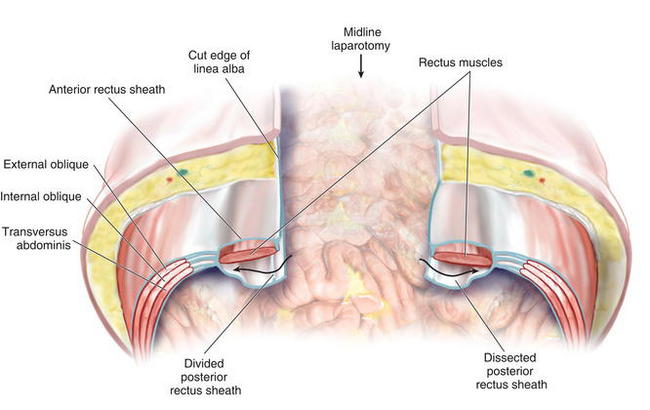

After a complete lysis of adhesions a towel is placed intraperitoneally to protect the underlying viscera. The posterior rectus sheath is divided vertically 1 cm or less from the edge of the linea alba and the division continues 5 cm cephalad to the hernia defect edge and 5 cm caudal to it (Fig. 14-10).

The posterior rectus sheath is divided vertically 1 cm or less from the edge of the linea alba and the division continues 5 cm cephalad to the hernia defect edge and 5 cm caudal to it (Fig. 14-10). The posterior rectus sheath is reflected posteriorly under tension and the rectus muscle is gently dissected off the ventral aspect of the sheath (Fig. 14-11).

The posterior rectus sheath is reflected posteriorly under tension and the rectus muscle is gently dissected off the ventral aspect of the sheath (Fig. 14-11). If it does not appear that the posterior rectus sheath will reapproximate in the midline under little to no tension, a posterior components separation technique (PCST) will be required.

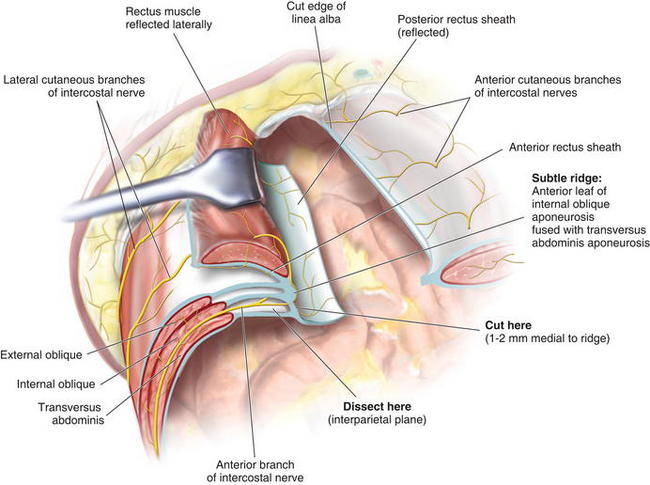

If it does not appear that the posterior rectus sheath will reapproximate in the midline under little to no tension, a posterior components separation technique (PCST) will be required. For the PCST, the dissection is carried to the lateral most extent of the rectus sheath. With a Richardson retractor reflecting the rectus laterally at this lateral extent, a subtle ridge becomes evident. This ridge is formed by the rolled over anterior leaf of the internal oblique aponeurosis as it fuses with the transversus abdominis aponeurosis to form the posterior rectus sheath (Fig. 14-12).

For the PCST, the dissection is carried to the lateral most extent of the rectus sheath. With a Richardson retractor reflecting the rectus laterally at this lateral extent, a subtle ridge becomes evident. This ridge is formed by the rolled over anterior leaf of the internal oblique aponeurosis as it fuses with the transversus abdominis aponeurosis to form the posterior rectus sheath (Fig. 14-12). By incising the fascia 1 to 2 mm medial to this ridge, the interparietal plane between internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle is accessed, and the incision is continued for the entire length of the skin incision and beyond (Fig. 14-13).

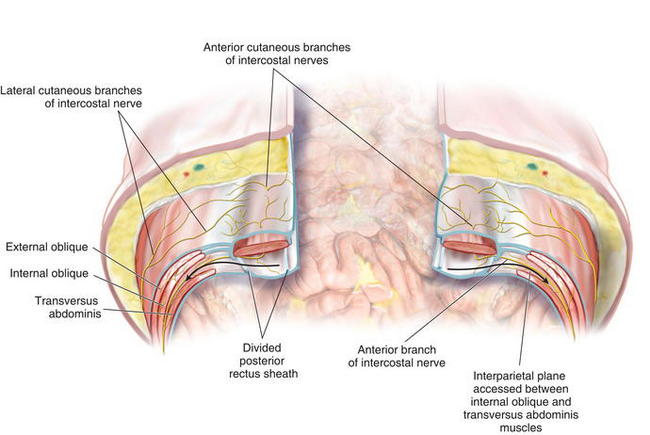

By incising the fascia 1 to 2 mm medial to this ridge, the interparietal plane between internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle is accessed, and the incision is continued for the entire length of the skin incision and beyond (Fig. 14-13). The interparietal plane is dissected far out laterally. This dissection disconnects the transversus abdominis muscle from the anterior components, allowing medial advancement of the posterior rectus sheath for complete peritoneal closure and medial rectus advancement for total abdominal wall reconstruction. PCST provides a well-vascularized and wide space for mesh placement with similar advancement to the Ramirez component separation without the need for a subcutaneous skin dissection and its attendant morbidity.

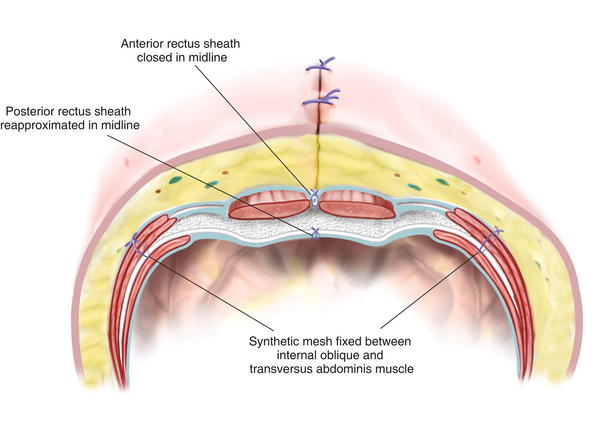

The interparietal plane is dissected far out laterally. This dissection disconnects the transversus abdominis muscle from the anterior components, allowing medial advancement of the posterior rectus sheath for complete peritoneal closure and medial rectus advancement for total abdominal wall reconstruction. PCST provides a well-vascularized and wide space for mesh placement with similar advancement to the Ramirez component separation without the need for a subcutaneous skin dissection and its attendant morbidity. The protective towel, which was placed intraperitoneally, is removed now, and the posterior rectus sheath is reapproximated in the midline with a slow-absorbing monofilament suture.

The protective towel, which was placed intraperitoneally, is removed now, and the posterior rectus sheath is reapproximated in the midline with a slow-absorbing monofilament suture. The synthetic mesh is placed in the retromuscular space and fixated with full-thickness permanent transabdominal sutures utilizing the Reverdin needle (Fig. 14-14).

The synthetic mesh is placed in the retromuscular space and fixated with full-thickness permanent transabdominal sutures utilizing the Reverdin needle (Fig. 14-14). Intraperitoneal Onlay of Mesh (IPOM) Repair

Intraperitoneal Onlay of Mesh (IPOM) Repair

If the retromuscular space is inaccessible because of inflammation, fibrosis, or rectus muscle absence, then an alternate technique for abdominal wall closure should be employed.

If the retromuscular space is inaccessible because of inflammation, fibrosis, or rectus muscle absence, then an alternate technique for abdominal wall closure should be employed. To ensure medial rectus reapproximation, a traditional Ramirez components separation may be performed.

To ensure medial rectus reapproximation, a traditional Ramirez components separation may be performed.4 Pearls/Pitfalls

Not identifying loss of abdominal domain preoperatively can place the surgeon in a difficult position intraoperatively where they may be unable to relocate the herniated contents back into the abdominal cavity and close the hernia defect.

Not identifying loss of abdominal domain preoperatively can place the surgeon in a difficult position intraoperatively where they may be unable to relocate the herniated contents back into the abdominal cavity and close the hernia defect. A large piece of Dualmesh (W.L. Gore, Elkton, MD) is circumferentially sewn to the fascial edge of the hernia defect, and the skin is closed temporarily over the top of the mesh.

A large piece of Dualmesh (W.L. Gore, Elkton, MD) is circumferentially sewn to the fascial edge of the hernia defect, and the skin is closed temporarily over the top of the mesh. Every 3 days, the patient returns to the operating room where a central ovoid shape of the mesh is excised and the cut mesh edges reapproximated. This technique slowly pulls the abdominal wall muscles to the midline.

Every 3 days, the patient returns to the operating room where a central ovoid shape of the mesh is excised and the cut mesh edges reapproximated. This technique slowly pulls the abdominal wall muscles to the midline. Once the remaining fascial gap is less than 5 cm, the mesh is completely excised and a Ramirez components separation is performed with fascial reinforcement (synthetic, biologic, or bioabsorbable) for complete abdominal wall reconstruction

Once the remaining fascial gap is less than 5 cm, the mesh is completely excised and a Ramirez components separation is performed with fascial reinforcement (synthetic, biologic, or bioabsorbable) for complete abdominal wall reconstruction Subcutaneous emphysema: Subcutaneous emphysema occurs almost uniformly in patients undergoing PPP because air leaks out along the tract of the insufflation catheter into the subcutaneous tissue. This is self-limited and, in our experience, has not required any intervention.

Subcutaneous emphysema: Subcutaneous emphysema occurs almost uniformly in patients undergoing PPP because air leaks out along the tract of the insufflation catheter into the subcutaneous tissue. This is self-limited and, in our experience, has not required any intervention. Nutrition: Patients undergoing PPP typically experience early satiety and even anorexia as a result of their increased intraabdominal pressure. Although every attempt should be made to encourage enteral alimentation, parenteral nutrition may be necessary while the patients are hospitalized for their insufflations.

Nutrition: Patients undergoing PPP typically experience early satiety and even anorexia as a result of their increased intraabdominal pressure. Although every attempt should be made to encourage enteral alimentation, parenteral nutrition may be necessary while the patients are hospitalized for their insufflations. Physiologic collapse during pneumoperitoneum: It is possible that a patient may become hemodynamically unstable during PPP. For this reason patients are kept in a close observation unit while they undergo insufflation, and vital signs are monitored closely. Should physiologic collapse occur at any point, the pneumoperitoneum may be promptly evacuated from the catheter, using wall suction.

Physiologic collapse during pneumoperitoneum: It is possible that a patient may become hemodynamically unstable during PPP. For this reason patients are kept in a close observation unit while they undergo insufflation, and vital signs are monitored closely. Should physiologic collapse occur at any point, the pneumoperitoneum may be promptly evacuated from the catheter, using wall suction.Carbonell A., Cobb W.S., Chen S.M. Posterior components separation during retromuscular hernia repair. Hernia: the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2008;12(4):359-362.

Mcadory R.S., Cobb W.S., Carbonell A.M. Progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum for hernias with loss of domain. The American surgeon. 2009;75(6):504-508. discussion 508–509

Moreno. Chronic eventrations and large hernias. Preoperative treatment by progressive pneumoperitoneum-original procedure. Surgery. 1947;22:945-953.

Tanaka E.Y., Yoo J.H., Rodrigues A.J., Utiyama E.M., Birolini D., Rasslan S. A computerized tomography scan method for calculating the hernia sac and abdominal cavity volume in complex large incisional hernia with loss of domain. Hernia. 2010;14(1):63-69.