8 Program Development and Implementation

The field of pediatric palliative care has evolved over the past decade in response to an escalating acknowledgment of need and a call to action by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report: When Children Die.1 A report from the First Forum for Pediatric Palliative Care in 20072 indicated that 31 children’s hospitals in the United States had pediatric palliative care programs and many more were developing them. Developing and implementing a palliative care program requires not only an understanding of the principles and practice of good pediatric palliative care, but also a familiarity with techniques to bring about change within an institution.

Phase I: Planning

Comprehensive planning from the earliest stages is essential (see Table 8-1). An early start-up strategy often involves convening an interdisciplinary task force. Five to seven members, representing different medical specialties, can identify needs and delineate a plan toward improving the institution’s provision of palliative care. The first task is to collect institution-wide information about practices, policies, and procedures related to palliative care. It is also critical to identify the many ways in which children with life-threatening conditions move through the organization. Early on, raising others’ awareness of the deficits in care delivery arouses a sense of need or urgency to make improvements.3,4 Identifying the many issues, barriers, and concerns related to the provision of care helps define the problem that the planning group is organizing to improve.

| Marshall resources for change | Define and promote the Program | Educate |

|---|---|---|

Identify early champions

The task force should expand over the first several months to include respected champions5—staff members who have demonstrated a special interest and expertise in palliative care. The central work of this group is to communicate what is needed, to generate institutional support, to identify possible solutions, and to organize improvements in the delivery of care. To succeed at transformative program development,3 it is critical to assemble individuals who are respected as achievers, experts, innovators, and leaders. They will be key spokespeople in creating a coalition for change.3,4 Recruitment focuses on individuals who have power within the institution through their influence and reputation; the skill to leverage organizational resources; and the clinical expertise to advance program development effectively.

Create a vision and action plan

Within the first few months, the task force must begin to articulate the program goals,6 which will eventually lead to a mission or vision statement.3,4,7 A well-articulated statement clearly defines pediatric palliative care7 and reveals core objectives that guide program planning. It will be necessary to explain the range of services that the program plans to offer. The start-up paths of programs can vary. For example, programs have begun with a primary focus on staff support and education,8 on advanced care planning and care coordination,9 or on services within the pediatric oncology population.10

Building a program is a daunting endeavor. It is fundamental to outline small, manageable steps; to use resources that already exist; and to establish a realistic timeline. The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) has designed a training methodology for programs at any stage of development. Expert guidance and written worksheets are combined with yearlong mentoring.11 The CAPC website, www.capc.org, also offers extensive program development resources.

Systems Assessment: Align with Institutional Goals

A helpful assessment activity is the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis,12 which can reveal the overt and covert power dynamics of the organization. This type of introspection can prepare the team for difficulties that may arise in program implementation, and it allows them to develop proactive strategies to avoid or minimize barriers.

Secure stakeholder support

Key administrative and clinical stakeholders should be consulted for their opinions and also recruited for support. Every informal or formal opportunity to influence stakeholders can be seized to publicize the program’s vision while building collegiality around a common purpose.3,4 The task force should be ready to communicate a compelling case for the program within the context of an informed understanding of the organization. Ultimately, the goal is to obtain endorsement of the endeavor; doing so secures essential stakeholder buy-in and paves the way for access to tangible resources needed to establish the program.

Conduct a needs assessment

Comparing the institution’s palliative care program efforts with those of other local, regional, and national institutions is also valuable. Ultimately, the data from benchmarking, the systems assessment, and the needs assessment will comprise the evidence that makes a solid case for program support to the institution and potential funding sources. The information also contributes to the development of a strategic business plan, and focuses clinical resources where they are most needed.13

Phase II: Creating the Foundation: Program Implementation

The tasks during this phase are to delineate both the scope and components of the pediatric palliative care services that will be offered, and to elucidate the logistics involved in service delivery and program marketing (see Table 8-2). Helpful steps include making a site visit to learn from other successful programs and building collaborative relationships with key personnel from departments within the hospital. Take time to learn the options; carefully consider what may work well in the organization, what may present unforeseen barriers, and how internal resources might be used to support program efforts. Throughout this phase, it will also be important to constantly analyze services given ongoing needs, gaps, strengths, and priorities, culminating in a multiyear business plan to ensure sustainability. Building a comprehensive program also includes developing expertise at interfacing effectively with community agencies, optimizing palliative care services across settings.

TABLE 8-2 Program Development Phase II: Program Implementation

| Find & create allies | Build team & define function | Show your worth |

|---|---|---|

Create an Identity: Choosing a Program Name

The program’s name should be selected by the time Phase II begins. Consistently using a name helps brand and market the program within the institution and the community. It is important for administrators and clinicians, as well as patients and their families, to be able to identify the program and to understand the focus for services. Clear identification makes it easier for those who need help to seek assistance from the program, and for those who appreciate the program’s efforts to give credit where credit is due. Some programs have chosen succinct, medical based names, with or without reference to palliative care, such as PACT: Pediatric Advanced Care Team, PACCT: Pediatric Advanced Comfort Care Team, and Pain and Palliative Care Team. Others have chosen a name that is associated with metaphoric imagery such as Footprints, Compass Care, and The Butterfly Program. Parents in particular have emphasized how an identified program name improves access to services. Some believe, however, that including palliative care in the name can be associated with diminished hope16,17 and associated with hospice. Other opinions focus on the importance of calling it what it is, and then working to dispel misunderstandings in the broader community. Be prepared for the ongoing challenge of addressing misperceptions around the term palliative care until the term is better understood by society.16

Service Delivery

The team

The current state of the art of pediatric palliative care requires effective, collaborative efforts of an interdisciplinary team, which includes the child, as appropriate, and the family.1,14,18 Team members may be selected from the original planning group. However, these individuals will need approval from their departments and the organization to allocate time in their current roles to provide palliative services throughout the hospital. Once assembled, the interdisciplinary pediatric palliative care team will work closely with a larger advisory group and/or task force to continue to direct the program’s growth.

Including representation from core disciplines—medicine, nursing, social work, psychology or psychiatry, child life, and spiritual care—is necessary for promoting interdisciplinary leadership, planning, practice, and acceptance. “The team approach ensures that the stresses and responsibilities of this work are shared.”19 Collaboration among various disciplines ensures a holistic approach to providing pediatric palliative care to patients and their families. The palliative care team may look different from one organization to another, depending on the size, resources, fiscal constraints, and culture of the institution. Hospital-based teams are often led by physicians. Additional staff may include an advanced practice nurse (APN) and a chaplain, and then rely on unit-based staff from child life, social work, case management, and pharmacy to round out interdisciplinary input as needed. Other models involve dedicated staff time for pediatric palliative care from the outset. The composition of the initial team is often a function of passionate interest, expertise, availability, budgetary constraints, and fit within the organizational structure.

Over time, the team’s composition may change to accommodate lessons learned, as well as availability of specialists. It is important to start and then to grow the team, and to not become stalled by an inability to staff the ideal team configuration. Resource pressures, the startup strategy, unclear utilization patterns, and other limitations may preclude dedicating a team of practitioners solely to palliative care at the outset. New staff can be added as emerging needs, program acceptance, and financial support are demonstrated. Other, more established programs can provide guidance in planning team membership and expansion. The CAPC website also has resources to help calculate staffing requirements, including projected needs based on program growth over the next several years.20

Practice model

Once the interdisciplinary team has been established, it is time to consider the following:

Coverage and referral considerations

Ideally, regardless of the program model, team members with training in palliative care should be available to provide round-the-clock assistance to hospital staff.13,14 Program size, demand, and allocated resources will dictate team availability. It is important to plan coverage realistically to both manage expectations and avoid burnout. Many programs provide on-site consults Monday through Friday, and offer phone consultation during off-hours. This model can help staff contend with patient needs, while protecting team members’ time off. With a consult model, the practical aspects of staffing require a larger, more formal commitment of dedicated physician or APN FTE to fulfill the clinical demands of a separate service. This expense can be partially offset by billing for eligible clinical services. State agencies, and even the institution itself, can have different rules specifying who can bill for care, so it is important to know these rules. However, at this time, it is not feasible for pediatric hospital-based programs in the United States to meet program costs through consult-billing reimbursements. Philanthropy and hospital support remain important sources for funding the pediatric palliative care program’s operations. (See Business Plan and Funding.)

As programs begin to announce their services, it will be important to address the referral process. The benefits of introducing palliative care as early as possible, such as at the time of diagnosis with a life-threatening condition, are widely advocated.1,14,21,22 From a practical standpoint, the biggest challenges are initiating these discussions and gaining entry from providers or family members for early palliative care team involvement. Marketing materials can address myths and misunderstandings that equate palliative care with giving up, taking away hope, or certainty that the child is dying. Teams need to prepare consistent responses to these types of concerns.

More often than not, a palliative care team may find that its involvement is requested late in the trajectory of a life-threatening event or when death is imminent. Ongoing education at multiple levels throughout the hospital will be necessary to effect culture change. Until there is a universal understanding of pediatric palliative care in hospitals, it will be necessary to reinforce two cardinal principles: curative or life prolonging therapies and palliative treatments can coexist; and this concurrent approach maximally benefits the family and child if it is implemented soon after the life-threatening condition is recognized. Likewise, pediatric palliative care programs need to recognize that the kinds of services needed at the time of diagnosis may differ considerably from the services required at the end of life.23

A number of resources offer suggestions as to how and when palliative care should be discussed.9,24 These guides often identify significant medical events or diagnoses, such as the need for a bone marrow transplant or the placement of a non-urgent tracheostomy, that serve as automatic triggers for a consult. With these triggers in place, clinicians may be more inclined to initiate pediatric palliative care earlier, thereby conforming to best practice standards.

Program operations and internal marketing

Referral intake and tracking forms for salient clinical data should be created and revised over time. In one common model, a nurse triages the request for assistance and involves other team members as needed. Other practical operational aspects include securing consultation and office space; setting up program contact information, and disseminating this information throughout the institution to promote access. (See program brochure examples at www.expertconsult.com.) These are essential marketing tactics that integrate the pediatric palliative care program into the hospital system.

When marketing the program to administrators, clinicians, foundations, and the community, it is imperative that the team be able to clearly describe the various services it can provide. The range of services (see Box 8-1) may change as resources are added and programs become more established. Services may expand to include outpatient pediatric palliative care consults, co-management for hospice care, perinatal palliative care, or a chronic pain clinic. The marketing aim is to effectively communicate the value added for accessing both palliative care resources and team members to help with the time-intensive, challenging care. The message to clinicians is that these extra measures enhance interdisciplinary care while continuing to involve the primary team(s).14,25

BOX 8-1 Pediatric Palliative Care Program Scope of Services

Resource Development

Contributing to the system

Resource development and implementation to improve the overall level of palliative care in a hospital also raises the awareness among generalist and subspecialty teams that they already provide services under the domain of palliative care.25 This awareness and use of pediatric palliative care resources raises the profile of the program, and thus becomes an effective internal marketing strategy. Efforts to establish a range of clinical care and educational resources should be directed at making “the right way the easy way.”7 This includes responding to the everyday practice needs of busy clinical staff and managers. It also requires a cooperative approach when redesigning operations so that these resources can incorporate palliative care practices into daily routines.7 For example, because most Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) deaths involve withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments, it may be useful to collaborate on Compassionate Extubation Guidelines with staff in the intensive care areas. Make a point to investigate the tension points or gaps that develop around policies and procedures, which are difficult and confusing to staff.

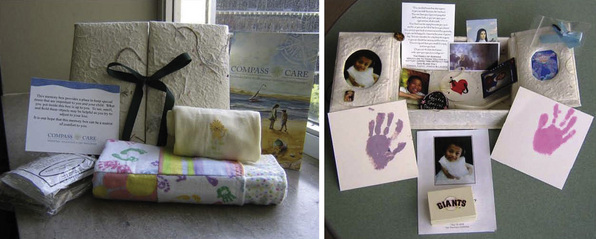

Clinical care resources, which make a difference at the point-of-care, may also include such tangible items as a comfort care room or comfort care cart, and baskets of non-perishable food delivered to a child’s room during family vigils at the end of life. End of life bedside practices can be standardized throughout the hospital by providing each unit with disposable cameras, memory boxes, and keepsake supplies to make handprints or footprints, to clip a lock of hair, and to measure the child’s height using decorative ribbon (Fig. 8-1). Many programs maintain resource libraries of anticipatory grief and bereavement literature for staff to give to families. Promoting varied resources and providing the necessary educational support puts consistent palliative care into action throughout the institution.

The role of education

Interdisciplinary education takes on importance early in pediatric palliative care program evolution and continues to be an integral function of the team as it champions best practices within the institution. Ongoing, institution-wide education will be essential to improve knowledge, attitudes, skills and behavior of all health professionals. These clinicians need to be fully versed about the need for high-quality palliative care, the indications for initiating palliative or end of life treatments, and the services provided by palliative care specialists.13

Not all members of the interdisciplinary team, especially in the early days of program development, will have completed a comprehensive, formal training program in pediatric palliative care. They will, however, come to the team with expertise and commitment born of experience in related fields. It will be pivotal to assess the needs of each member of the core team and address any deficits in discipline-specific or interdisciplinary palliative care knowledge. (See Chapter 11.)

The quality of the program as an interdisciplinary effort will be enhanced if collaborative education begins early and the process is embedded in the team’s day-to-day functions. When this occurs, the full potential for using all of the heterogeneous and complementary perspectives of a team approach is realized. It is necessary for all members of the core group to acquire skills in working as an interdisciplinary team, respecting and using each other’s skills rather than working as parallel, non-collaborating agents. (See Chapter 16.) Team effectiveness can be strengthened by using input from various disciplines to craft program educational goals and by modeling interdisciplinary teamwork at every teaching opportunity, especially at the bedside.

The role of communication

Effective, collaborative communication is indispensable when striving for the highest quality of palliative care and has been described as one of the most common procedures in medicine. When performed well, communication conveys both reciprocal information and compassion, justifying its importance as a core competency for the pediatric palliative care team. Effective communication is also paramount to building a cohesive team and promoting positive, collaborative exchanges with referring staff, which ultimately facilitates both continuity and quality of care. Its role and importance have been emphasized in the literature in multiple research studies demonstrating key features and implications.17,26–31

Many palliative care teams introduce documentation tools to facilitate communication, decision making, and continuity of care. Examples include the Five Wishes advanced illness/directive booklets (available at www.agingwithdignity.org/index.php),32 the Seattle Decision Making Tool,33 and Palliative Care Summary Plans9 that are distributed among various inpatient and community teams providing care. These communication tools, shared between the family and all providers, facilitate a mutual understanding of the goals of care and the treatment plan in the context of the child’s changing needs.

Effective communication also includes consistent documentation of palliative care team consults or involvement; information discussed with providers, patients, and/or family members; and recommendations. Consult forms, checklists, and summary or discharge forms may be helpful in disseminating information. The quality, coordination, and continuity of care will be compromised without proper documentation. Charting needs to specify what has been addressed, what gaps in care remain, the family’s preferences and wishes, and what medical, psychosocial, and spiritual interventions are in agreement with the goals of care.17

The role of pain and symptom management

Developing pain and symptom management skills are a pivotal component of building a successful pediatric palliative care program.18,34 Established best practices have advanced a trend in pediatrics to merge pain and palliative care programs in the United States and abroad.35 From an economical and practical standpoint, this kind of joint program may be advantageous particularly for smaller institutions, where sharing resources allows for increased continuity, productivity, and efficiency while conserving program costs. Integrating pain and palliative care programs, or at minimum establishing a formal, collaborative working relationship between them, helps ensure relief of suffering and optimizes quality of life throughout the continuum of care.35

The role of bereavement care

Services to help ill children and their families cope with anticipatory grief, the end-of-life experience, and the ensuing bereavement are integral to pediatric palliative care and hospice programs. (See Chapter 5.) A growing body of literature suggests that the grief experienced when a child dies is more protracted and complex than the grief associated with adult death.36–38 Providing bereavement care is unique among hospital services rendered because much of the support offered occurs when the actual patient is deceased. The family then becomes the focus of care.

The role of staff support

Addressing staff support and team wellness is widely recognized as an essential endeavor.1,13,14 The intensity of care and emotional demands experienced by staff places them at risk for compassion fatigue, moral distress and burnout. Promoting staff support and self-care measures is vital in preserving effective functioning for the palliative care team, as well as for the staff who provide bedside care. Taking the time to process the intense and highly emotional clinician-patient-family experiences recognizes the humanistic and compassionate nature of this work.

Creating a Business and Financial Plan

There are core elements included in a business plan that can be tailored to meet specific needs at various stages of program development (see Box 8-2). The introduction provides supporting background information, outlining the needs and rationale for the program. For this section, the team carefully selects and expands on the data from the systems and needs assessments. The document explains how the program cooperatively shares and builds upon existing resources. A central message emphasizes the value added to the institution, and the breadth and depth of services provided by the pediatric palliative care program. The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) has outlined compelling points that are useful in justifying program development (see Box 8-3). These points can be personalized to address institution-specific data when presented to hospital administrators.

BOX 8-2 Business Plan Components

Adapted from CAPC resources on business plan development: The Business Plan (Level I): Worksheets; Appendix 3.6: PowerPoint – Business Plan Basics; Module 2: Creating Compelling Business and Financial Plan; http://www.capc.org/building-a-hospital-based-palliative-care-program/designing/presenting-plan/index_html (Building a Palliative Care Program-Presenting the Business Plan)

BOX 8-3 Making the Case for a Hospital Based Palliative Care Program

Adapted from “The Case for Hospital-Based Palliative Care” Center to Advance Palliative care. Accessed online 8.10.2010. http://www.capc.org/building-a-hospital-based-palliative-care-program/case/hospitalbenefits/ www.capc.org/support-from-capc/capc_publications/making-thecase.pdf

It is essential to include a detailed, multi-year program budget, indicating direct program expenses: salaries with benefits; marketing costs; equipment and supplies; staff education; and specific program resources (e.g., memorials, educational literature, and comfort carts). In addition, the financial analysis includes revenue streams, such as medical center support for salaries and/or operations, as well as income from consult billing, philanthropy, and grants. The business plan also presents outcome data that the team tracks to demonstrate quality of care and program impact. Typical categories include operational, customer, clinical, and financial metrics.13,39

Ultimately, the business plan needs to speak the language of those who are running the institution. It should reflect their goals and their priorities, be fiscally responsible and sustainable, and promote the necessary changes to fuel the growth of good interdisciplinary palliative care.25 It is prudent to present the plan in such a way that it does not appear to be asking for unlimited resources and financial support but rather places the program in partnership with the institution.25 The business plan presents evidence that makes a case for action, clearly stating what is needed from the institution to develop or expand the palliative care program.40 Be careful to match expected workload to allocated resources, avoiding the precedent of giving away services without adequate institutional support. A business plan is not a static document and will need to be revised repeatedly as the program changes and expands.

Building a business case with cost-saving financial metrics is a significant challenge for pediatric palliative care programs trying to start, grow, or sustain their services.41 It is widely recognized that pediatric programs have not been able to directly apply the same financial model of cost neutrality and cost avoidance that exists in the Diagnostic Related Groups driven adult healthcare environment. Although similar work is being done in pediatrics to create reliable cost accounting methods and templates to calculate appropriate staffing, volume, and projected income, pediatric programs are still forced to secure financial support from their institutions and from outside sources.41

A strong argument about generating or saving money may not be the best strategy for garnering institutional support. Rather, the most compelling value proposition lies in aligning with the priorities, needs, and challenges of the institution.41 For example, if ICU bed capacity is an issue, work with the administration to identify throughput issues and then direct program efforts toward relieving ICU bottlenecks, preventing ICU diversions, and making room for elective surgeries. Also, institutions place great value on improving patient and family satisfaction scores, pain scores, and staff retention. Palliative care programs become more valuable to the institution when they can demonstrate how the program might help these areas and increase opportunities for marketing the institution within the community.

Programs need to work closely with finance staff, including billers and coders, to understand how to maximize revenues given the constraints and payer mix at the institution. See if other specialty services bill for symptom management; if they are not, the pediatric palliative care team should do so whenever appropriate. Learn about billing from other adult and pediatric palliative care programs, as well as from educational resources for understanding finances.42 Explore how and where the institution loses revenue, as well as the circumstances where it maximizes revenue. For example, Children’s of Minnesota conducted a quality study and found that the pediatric palliative care team’s involvement saved money, and reduced hospital admits and days, as well as Emergency Department (ED) visits.43 Realistically though, pediatric palliative care often involves aggressive and expensive therapy, which may continue for weeks, months, or years. Pediatric palliative care programs can demonstrate their roles in maximizing efficient, coordinated care that optimizes quality of life despite intense medical and practical needs.41 More analysis needs to be done within the pediatric community to find the financial impact of providing pediatric palliative care and end-of-life services to children in the hospital and home.

Because reimbursement for the time clinicians spend with patients and families is sub-optimal, it is critical to solicit other funding for the program’s survival. Philanthropic donations and grants provide not only direct payment to the institution, but also recognition and valuable community public relations. Most administrations look favorably on these contributions to the overall budget25 and to the institution’s reputation. The challenge here is to allocate time to work closely with the development office, ensuring its understanding of program objectives and services, and advocating fundraising for specific aspects of the program. Prepare program talking points, fundraising proposals, patient impact stories, and a wish list of both small and large program items so that both development officers and pediatric palliative care team members are always ready to meet with potential donors.

Interfacing with Community Partners

Understanding unique constraints

Children with complex, life-threatening conditions have spent significant amounts of time in hospitals because of limitations in community-based services. Children and their families can feel an immense sense of support from hospital clinicians, often believing that the hospital represents a safe haven. That said, the hospital remains an unnatural and distorted place to live out one’s childhood. Research and practice experience validate that a child’s development and the family’s coping are best served at home with adequate resources.44 It is therefore important that pediatric palliative care teams develop strategic partnerships to enable safe, coordinated, and continuous care between the hospital and community.

Advocacy: Demand Driving Resource Development

Given financial constraints and limited staffing expertise, it makes sense to create cooperative networks among pediatric palliative care consultants, inpatient hospitals, and home-based service providers.8 Many children travel to regional specialty centers, and then are also seen at local hospitals and clinics for routine care. Networking with potential agencies can help identify the kinds of services available, barriers to overcome, and limitations to be considered before planning for a specific child’s urgent needs. Effective coordination of services can go a long way toward reducing the stress on children and their families, while also creating efficiencies that benefit organizations which provide or pay for this complex level of care.

In response to these various constraints, community-based home care agencies most often work closely with pediatric hospices and/or palliative care specialists, or through adult-oriented hospice agencies that have been willing to extend their services to include pediatrics. Each group may have a different set of skills and expertise as their standard. Collaborative relationships with other providers can help wrap around these core services and create a competent network of comprehensive care. In addition, partnerships with key staff at the identified children’s hospital are also important. The goal is to create a service delivery system that successfully connects hospital and community providers, enabling the child access to coordinated care in each setting that shares common treatment goals. (See clinical vignette.)

Phase III: Ensuring Sustainability

During Phase 3, program development is focused on embedding, strengthening, and sustaining the program, ultimately to make it indispensable to the organization. Sustainability requires ongoing goal setting, not just for program startup, but also for mid- and long-term program development. Anticipating growth, changes in resources, and staffing needs all assist program-planning efforts over the long haul (see Table 8-3).

TABLE 8-3 Program Development Phase III: Ensuring Sustainability

| Improve services & quality | Take care of what you have | Address long-term needs |

|---|---|---|

During this phase, the program achieves credibility, accomplishes good work, and is well accepted by administrative, clinician, and family stakeholders.45 The program has matured in its capability to offer services with depth of knowledge, skills, and resources, serving needs in many if not all areas where children and families are cared for within the organization. By the end of this phase, the program clearly will be able to validate that it makes a significant difference in many arenas, that successful practices have been adopted throughout the institution, and that palliative care has been woven into the fabric of the institution.

Phase IV: Surviving Success

Surviving success requires effective and forward-thinking management of program growth, increased patient care volume, and competing priorities (see Table 8-4). As experience grows, staff members and the team develop expertise, economies of scale, and greater efficiency. With this increased capacity the same number of staff members can provide more services—up to a point.

| Strive for continued excellence | Maintain professional vitality |

|---|---|

1 Field M.J., Behrman R.E., editors. For the Institute of Medicine Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and their Families. “When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and their Families.”. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003.

2 Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota. www.childrensmn.org/services/painpalliativecare.

3 Kotter J. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harv Bus Rev. 2007:1-10.

4 Periyakoil V.S. Change management: the secret sauce of successful program building. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):329-330.

5 Meier D.E. Ten steps to growing palliative care referrals. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(4):706-708.

6 Radwany S., Mason H., Clarke J.S., et al. Optimizing the success of a palliative care consult service: how to average over 110 consults per month. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008.

7 Byock I., Twohig J.S., Merriman M., et al. Promoting excellence in end-of-life care: a report on innovative models of palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(1):137-151.

8 Meier D.E., Beresford L. Pediatric palliative care offers opportunities for collaboration. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(2):284-289.

9 Toce S., Collins M.A. The FOOTPRINTS model of pediatric palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(6):989-1000.

10 Duncan J., Spengler E., Wolfe J. Providing pediatric palliative care: PACT in action. Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32(5):279-287.

11 www.capc.org/palliative-care-leadership-initiative/overview/curriculum/pclc_peds/. last accessed 5.27.10

12 Learned E.P., Roland Christiansen C., et al. Business Policy, Text and Cases. Homewood, Ill: RD Irwin, Publisher, 1969.

13 Weissman D.E., Meier D.E. Operational features for hospital palliative care programs: consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(9):1189-1194.

13a A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum, 2006.

14 American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2 Pt 1):351-357.

15 Gwyther LP, Altilio T, Blacker S, Christ G, Csikai EL, Hooyman N, et al. Social work competencies in palliative and end-of-life care. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2005;1(1):87-120.

16 Morstad Boldt A., Yusuf F., Himelstein B.P. Perceptions of the term palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5):1128-1136.

17 Zhukovsky D.S., Herzog C.E., Kaur G., et al. The impact of palliative care consultation on symptom assessment, communication needs, and palliative interventions in pediatric patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):343-349.

18 Standards of Practice for Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice. National Hospice and Palliative Care. Organization. Virginia: Alexandria, 2009;1-31.

19 The Case for Hospital Palliative Care Improving Palliative Care. Reducing Costs. p. 15. Interview with Diane Meier, MD, Director, Center to Advance Palliative Care. http://www.capc.org/support-from-capc/capc_publications/making-the-case.pdf/. file_view

20 www.capc.org/building-a-hospital-based-palliative-care-program/implementation/staffing/. ;last accessed 5.27.10.

21 Frager G. Pediatric palliative care: building the model, bridging the gaps. J Palliat Med. 1996;12(3):9-12.

22 Mack J.W., Wolfe J. Early integration of pediatric palliative care: for some children, palliative care starts at diagnosis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(1):10-14.

23 Thompson L.A., Knapp C., Madden V., et al. Pediatricians’ perceptions of and preferred timing for pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):e777-e782.

24 Friebert S., Osenga K. Pediatric Palliative Care Referral Guide. www.capc.org/tools-for-palliative-care-programs/clinicaltools/. ;last accessed 5.27.10.

25 Portenoy R., Heller K.S. Developing an integrated department of pain and palliative medicine. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(4):623-633.

26 Mack J.W., Hilden J.M., Watterson J., et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9155-9161.

27 Contro N., Larson J., Scofield S., et al. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):14-19.

28 Contro N.A., Larson J., Scofield S., et al. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248-1252.

29 Meyer E.C., Rithholz M.D., Burns J.P., et al. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents and priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117:649-657.

30 Hinds P.S., Drew D., Oakes L.L., et al. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9146-9154.

31 Hsiao J.L., Evan E.E., Zeltzer L.K. Parent and child perspectives on physician communication in pediatric palliative care. Palliative Support Care. 2007;5(4):355-365.

32 Five Wishes advanced illness/directive booklets. www.agingwithdignity.org/five-wishes-resources.php.. Accessed May 27, 2010

33 Hays R.M., Valentine J., Haynes G., et al. The Seattle Pediatric Palliative Care Project: effects on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):716-728.

34 National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. ed 2. 2009. www.nationalconsensusproject.org/. ;last accessed 5.27.10

35 Friedrichsdorf S.J., Remke S., Symalla B., et al. Developing a pain and palliative care programme at a US children’s hospital. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2007;13(11):534-542.

36 Rando T.A. Parental Loss of a Child. Champaign, Il: Research Press, 1986.

37 Davies R. New understanding of parental grief: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46:506-513.

38 Kreicbergs U., Lannen P., Onelov E., et al. Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: impact of professional and social support on long term outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3308-3314.

39 http://www.capc.org/building-a-hospital-based-palliative-care-program/measuring-quality-and-impact/. ; last accessed 5.27.10

40 Spragens L.H. Creating Compelling Business and Financial Plans. 2003. Accessed online at www.capc.org/support-from-capc/capc_presentations/ca-2003/module-2.ppt

41 Friebert S. Making the Financial Case for Pediatric Palliative Care. 2009. CAPC web seminar, July 30

42 http://capc.org/tools-for-palliative-care-programs/billing/overview-claims-payment/20090611.ppt/. ;Date accessed 5.27.10

43 Friedrichsdorf S.J., et al. Making the case for pediatric palliative care: one example. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(2):129-138.

44 Dussel K., Hilden W., Moore C, Turner BG:. Looking beyond where children die: determinants and effects of planning a child’s location of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(1):33-43.

45 Bruera E. The development of a palliative care culture. J Palliat Med. 2004;20(4):316-319.

Bruce A., Boston P. The changing landscape of palliative care: emotional challenges for hospice and palliative care professionals. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2008;10(1):49-55.

Dabbs D., Butterworth L., Hall E. Tender mercies: increasing access to hospice services for children with life threatening conditions. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32(5):311-319.

Dickens D.S. Building competence in pediatric end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(7):617-622.

Feudtner C. Collaborative communication in pediatric palliative care: a foundation for problem solving and decision making. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:583-607.

Feudtner C., Christakis D.A., Connell F.A. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of washington state, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205-209.

Feudtner C., Christakis D.A., Zimmerman F.J., et al. Characteristics of deaths occurring in children’s hospitals: implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):887-893.

Gale G., Brooks A. Implementing a palliative care program in a newborn intensive care unit. Adv Neonatal Care. 2006;6(1):37-53.

Gerhardt C.A., Grollman J.A., Baughcum A.E., et al. Longitudinal evaluation of a pediatric palliative care educational workshop for oncology fellows. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):323-328.

Golan H., Bielorai B., Grebler D., et al. Integration of a palliative and terminal care center into a comprehensive pediatric oncology department. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(5):949-955.

Harper J., Hinds P.S., Baker J.N., et al. Creating a palliative and end-of-life program in a cure-oriented pediatric setting: the zig-zag method. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2007;24(5):246-254.

Hatzmann J., Heymans H.S., Ferrer-i-Carbonell A., et al. Hidden consequences of success in pediatrics: parental health-related quality of life—results from the care project. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):e1030-e1038.

Homer C.J., Marino B., Cleary P.D., et al. Quality of care at a children’s hospital: the parents’ perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1123-1129.

Hubble R.A., Ward-Smith P., Christenson K., et al. Implementation of a palliative care team in a pediatric hospital. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23(2):126-131.

Johnston D.L., Nagel K., Friedman D.L., et al. Availability and use of palliative care and end-of-life services for pediatric oncology patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(28):4646-4650.

Knapp C.A., Thompson L.A., Vogel W.B., et al. Developing a pediatric palliative care program: addressing the lack of baseline expenditure information. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26(1):40-46.

Linton J.M., Feudtner C. What accounts for differences or disparities in pediatric palliative and end-of-life care? A systematic review focusing on possible multilevel mechanisms. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):574-582.

Long T., Hale C., Sanderson L., et al. Evaluation of educational preparation for cancer and palliative care nursing for children and adolescents in England. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(1):65-74.

Mack J.W., Joffe S., Hilden J.M., et al. Parents’ views of cancer-directed therapy for children with no realistic chance for cure. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4759-4764.

McCallum D.E., Byrne P., Bruera E. How children die in hospitals. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:417-423.

Meier D.E., Beresford L. The palliative care team. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):677-681.

Michelson K.N., Ryan A.D., Jovanovic B., et al. Pediatric residents’ and fellows’ perspectives on palliative care education. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(5):451-457.

O’Connor M., Fisher C., Guilfoyle A. Interdisciplinary teams in palliative care: a critical reflection. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2006;12(3):132-137.

Rushton C.H., Reder E., Hall B., et al. Interdisciplinary interventions to improve pediatric palliative care and reduce health care professional suffering. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(4):922-933.

Tan G.H., Totapally B.R., Torbati D., et al. End-of-life decisions and palliative care in a children’s hospital. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(2):332-342.

Ward-Smith P., Korphage R.M., Hutto C.J. Where health care dollars are spent when pediatric palliative care is provided. Nurs Econ. 2008;26(3):175-178.

Ward-Smith P., Linn J.B., Korphage R.M., et al. Development of a pediatric palliative care team. J Pediatr Health Care. 2007;21(4):245-249.

Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Klar N., et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326-333.

Wolfe J., Klar N., Grier H.E., et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284(19):2469-2475.