Professional Caring and Ethical Practice

AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CRITICAL-CARE NURSES (AACN) VISION, MISSION, AND VALUES (AACN, 2002)

Values

1. Be accountable to uphold and consistently act in concert with ethical values and principles

2. Advocate for organizational decisions that are driven by the needs of patients and their families

3. Act with integrity by communicating openly and honestly, keeping promises, honoring commitments, and promoting loyalty in all relationships

4. Collaborate with all essential stakeholders by creating synergistic relationships to promote common interest and shared values

5. Provide leadership to transform thinking, structures, and processes to address opportunities and challenges

6. Demonstrate stewardship through fair and responsible management of resources

7. Embrace lifelong learning, inquiry, and critical thinking to enable each to make optimal contributions

8. Commit to quality and excellence at all levels of the organization, meeting and exceeding standards and expectations

9. Promote innovation through creativity and calculated risk taking

10. Generate commitment to and passion for the organization’s causes and work

SYNERGY OF CARING

What Nurses Do (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2003)

1. Attend to the full range of human experiences of and responses to health and illness

2. Integrate objective data with knowledge of the patient as a person and understanding of the patient’s subjective experience

3. Apply scientific knowledge to the process of diagnosis and treatment of the responses to health and illness

What Critical Care Nurses Do (Medina, 2000)

1. Critical care nurses deal with human responses to life-threatening problems

2. The Scope of Practice includes all ages and involves a dynamic interaction between the critically ill patient, the patient’s family, the critical care nurse, and the environment

3. The framework of practice includes the scientific body of specialized knowledge, an ethical model for decision making, a commitment to interdisciplinary collaboration, and the AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care. Critical care nurses rely on this framework to do the following (Bell, 2002, p. 44):

a. Support and maintain the physiologic stability of patients

b. Assimilate and prioritize information sources to take immediate and decisive patient-focused action

c. Respond with confidence and adapt to rapidly changing patient conditions

d. Respond to the unique needs of patients and families coping with unanticipated treatment, quality of life, and end-of-life decisions

e. Manage appropriately the interface between the patient and technology that may be threatening, invasive, and complex so that human needs for a safe, respectful, healing, humane, and caring environment are established and maintained

f. Monitor and allocate critical care services, recognizing the fiduciary role of nurses working in a resource-intensive environment

The Environment of Critical Care

1. Complexity requiring vigilance: Critically ill patients require complex assessment and therapies, high-intensity interventions, and continuous vigilance

2. Organizational model for a humane, caring, and healing environment

a. The critical care nurse works with an interdisciplinary team to create a humane, caring, and healing environment. There are five elements of an organizational model for health and healing (Malloch, 2000; Molter, 2003):

i. Common values of health as a function of mind-body-spirit interrelationships

ii. Patient and family–centered philosophy

iii. Physical environment that supports healing

iv. Use of complementary and alternative therapies as well as conventional therapies

b. The critical care nurse is a constant in the environment and works to develop an organizational culture that supports the following (Bell, 2002, p. 45):

i. Providers that act as advocates on behalf of patients, families, and communities

ii. The dominance of the patient’s and family’s values

iii. Practice based in research and driven by outcomes

vi. The fostering of leadership at all levels and in all activities

vii. Lifelong learning as fundamental to professional growth

viii. Optimization of existing talents and resources

a. An Institute of Medicine (IOM) study notes the occurrence of a significant number of deaths related to health care service delivery processes (IOM, 1999)

b. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) established National Patient Safety Goals in 2005 (JCAHO, 2006). The goals include the following*:

i. Improve the accuracy of patient identification by using at least two patient identifiers when administering medications or blood products, taking blood samples and other specimens for clinical testing, or providing any other treatments or procedures.

ii. Improve the effectiveness of communication among caregivers by reading back verbal or telephone orders and critical laboratory results; standardizing abbreviations, acronyms, and symbols not to be used in the organization; improving the timeliness of receiving critical test results and values; and standardizing the “hand off” of communications.

iii. Improve the safety of using medications by standardizing and limiting the number of drug concentrations available in the organization, identifying and reviewing a list of look-alike/sound-alike drugs, taking action to prevent errors involving the interchange of these drugs, and labeling all medications, medication containers, or other solutions in perioperative and other procedural settings.

iv. Reduce the risk of health care–associated infections by complying with current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention hand hygiene guidelines and managing as sentinel events all identified cases of unanticipated death or major permanent loss of function associated with a health care–associated infection.

v. Accurately and completely reconcile medications across the continuum of care by implementing a process to obtain and document a complete list of the patient’s current medications upon the patient’s admission to the organization, by comparing the medications on the list to those available in the organization and by communicating the list to the next provider of service when a patient is referred or transferred.

vi. Reduce the risk of patient harm resulting from falls by implementing a fall-reduction program and evaluating its effectiveness.

The “Synergy” of the AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care

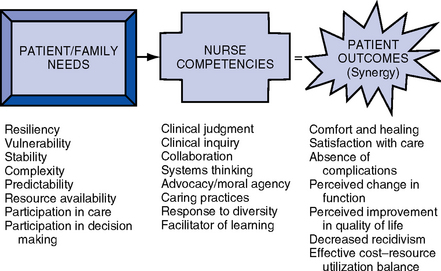

1. Synergistic practice and patient and family safety: The AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care (Curley, 1998) describes nursing practice in terms of the needs and characteristics of patients. The model’s premise is that the needs of the patient and family system drive the competencies required by the nurse. When this occurs, synergy is produced and optimal outcomes can be achieved. Buckminster Fuller stated that “synergy is the only word in our language that means behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the separately observed behaviors of any of the system’s separate parts or any subassembly of the system’s parts” (cited in Carlson, 1996, p. 92). The synergy created by practice based on the Synergy Model helps the patient-family unit safely navigate the health care system.

2. The Synergy Model and ethical practice: The Synergy Model provides a foundation for addressing ethical concerns related to critical care nursing practice (McGaffic, 2001). The model focuses on the characteristics of patients, the competencies needed by the critical care nurse to meet the patient’s needs based on these characteristics, and the outcomes that can be achieved through the synergy that develops when nursing competencies are driven by the patient’s needs. AACN is committed to helping members deal with ethical issues through education (Glassford, 1999).

AACN SYNERGY MODEL FOR PATIENT CARE

In 1992, AACN developed a vision of a health care system driven by the needs of patients and their families in which critical care nurses can make their optimal contribution. AACN Certification Corporation in tandem was rethinking the contributions of certification to the care of patients. Patient needs and outcomes must be the central focus of certification. A think tank was convened in 1992 to reconceptualize certified practice (Caterinicchio, 1995; Villaire, 1996).

Purpose

Prior to development of the Synergy Model, the certification process conceptualized nursing practice according to the dimensions of the nurse’s role, the clinical setting, and the patient’s diagnosis. The Synergy Model reconceptualized certified practice to recognize that the needs and characteristics of patients and families influence and drive the competencies of nurses. The synergy that develops when this occurs influences the outcomes of individual patients, the nurse’s practice, and the organization. A separate think tank in 1996 identified the potential outcomes (Biel, 1997).

Overview of the Synergy Model (AACN Certification Corporation, 2003, 2004)

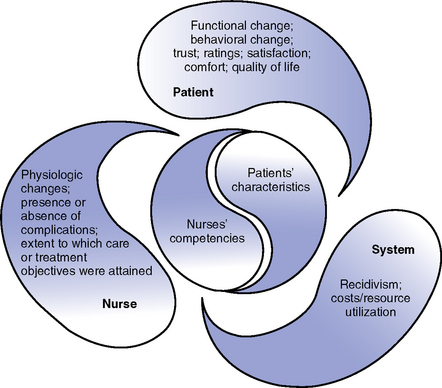

1. Description of the Synergy Model (Figure 1-1): The synergy that occurs when patient and family characteristics or needs drive the competencies that nurses need to achieve optimal outcomes for the patient, nurse, and organization

2. Assumptions of the Synergy Model (AACN Certification Corporation, 1998)

a. All patients are biologic, psychologic, social, and spiritual entities who have similar needs and experiences at a particular developmental stage across wide ranges or continua from health to illness. The whole patient must be considered. More compromised patients have more complex needs.

b. The dimensions of a nurse’s practice as determined by the needs of a patient and family can also be described along continua

c. The patient, family, and community all contribute to providing a context for the nurse-patient relationship

d. Optimal outcomes can be achieved through the synergy effected by alignment of nurse competencies with patient and family needs. A peaceful death can be an acceptable outcome.

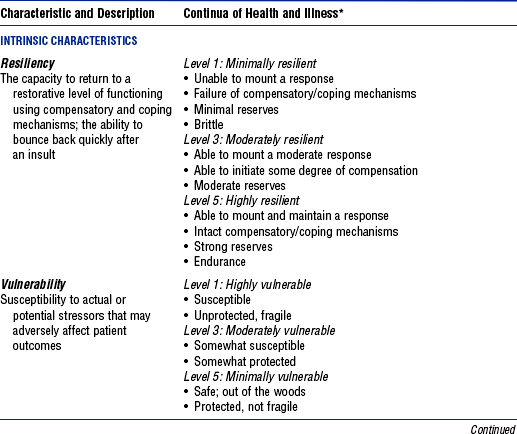

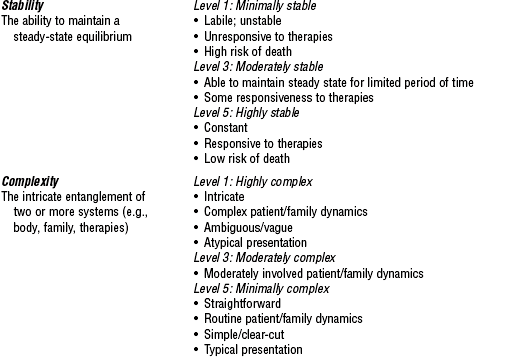

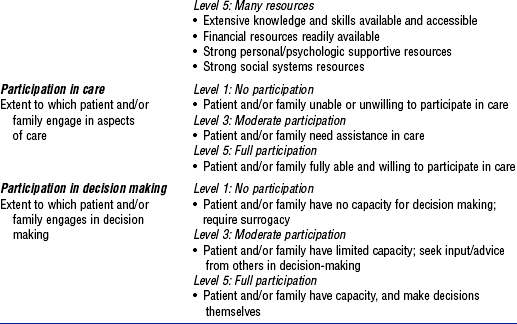

3. Patient characteristics: Characteristics unique to each patient and family span the continua of health and illness. The first five are intrinsic to the patient and the last three are extrinsic. Each characteristic is described in terms of a range of levels from 1 to 5 in Table 1-1 (AACN Certification Corporation, 1997, 2004).

TABLE 1-1

The Synergy Model—Patient Characteristics

From AACN Certification Corporation.

*Note that the continua of health and illness levels vary in order of rating based on the characteristic.

a. Resiliency: The capacity to return to a restorative level of functioning using compensatory and coping mechanisms; the ability to bounce back quickly after an insult

b. Vulnerability: Susceptibility to actual or potential stressors that may adversely affect patient outcomes

c. Stability: The ability to maintain a steady-state equilibrium

d. Complexity: The intricate entanglement of two or more systems (e.g., body, family, therapies)

e. Predictability: A characteristic that allows one to expect a certain course of events or course of illness

f. Resource availability: Extent of resources (e.g., technical, fiscal, personal, psychologic, and social) the patient, family, and community bring to the situation

g. Participation in care: Extent to which the patient and/or family engages in aspects of care

h. Participation in decision making: Extent to which the patient and/or family engages in decision making

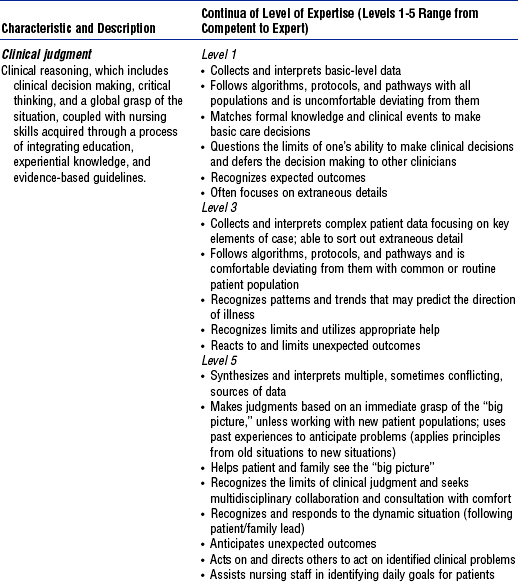

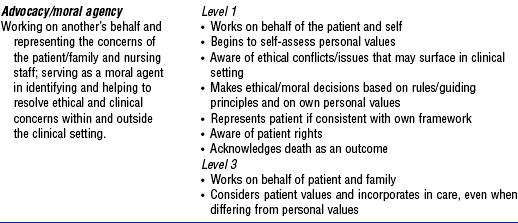

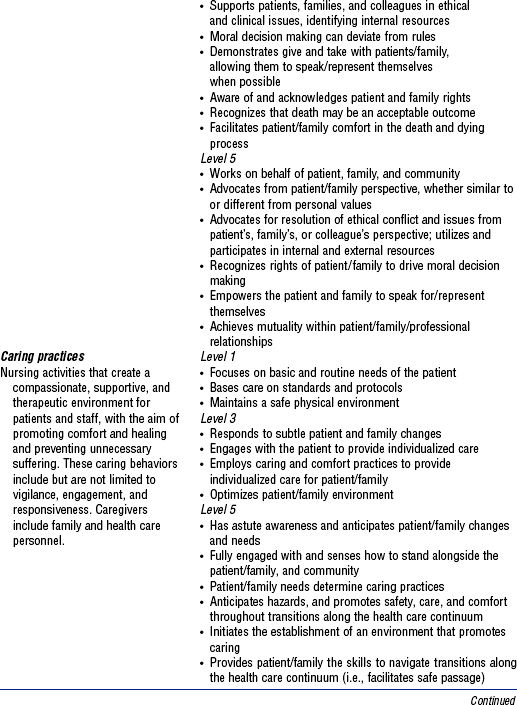

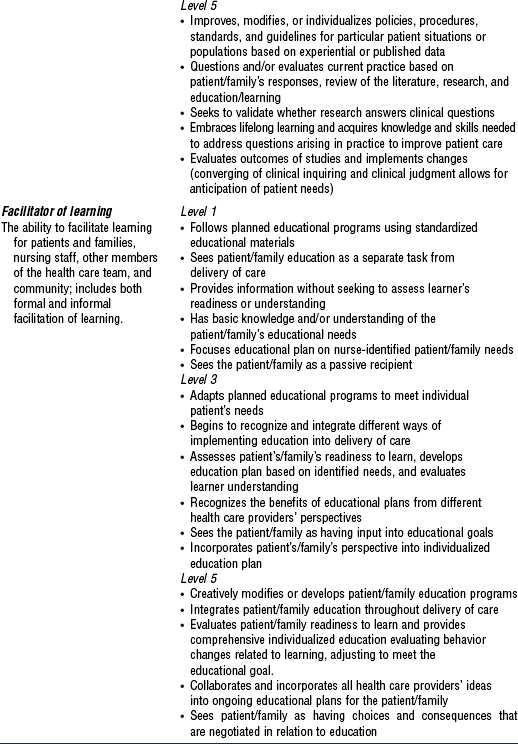

4. Nurse characteristics: Nursing care is an integration of knowledge, skills, experience, and individual attitudes. The continua of nurse characteristics needed are derived from the patient’s needs and range from a competent to expert level as outlined in Table 1-2.

TABLE 1-2

The Synergy Model—Nurse Characteristics

From AACN Certification Corporation and PES: Final report of a comprehensive study of critical care nursing practice. Aliso Viejo, Calif, 2004, The Corporation.

a. Clinical judgment: Clinical reasoning, which includes clinical decision making, critical thinking, and a global grasp of the situation, coupled with nursing skills acquired through a process of integrating education, experiential knowledge, and evidence-based guidelines

b. Advocacy/moral agency: Working on another’s behalf and representing the concerns of the patient/family, and nursing staff; serving as a moral agent in identifying and helping to resolve ethical and clinical concerns within and outside the clinical setting

c. Caring practices: Nursing activities that create a compassionate, supportive, and therapeutic environment for patients and staff, with the aim of promoting comfort and healing and preventing unnecessary suffering. These caring behaviors include but are not limited to vigilance, engagement, and responsiveness. Caregivers include family and health care personnel.

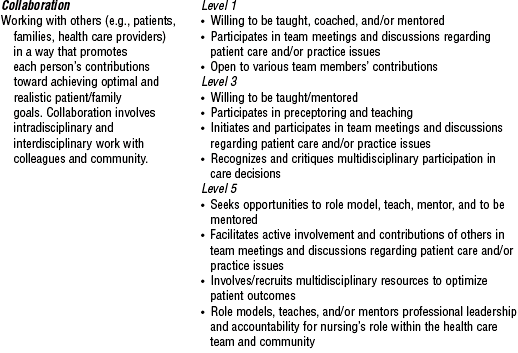

d. Collaboration: Working with others (e.g., patients and families, health care providers) in a way that promotes each person’s contributions toward achieving optimal and realistic patient and family goals. Collaboration involves intradisciplinary and interdisciplinary work with colleagues and community.

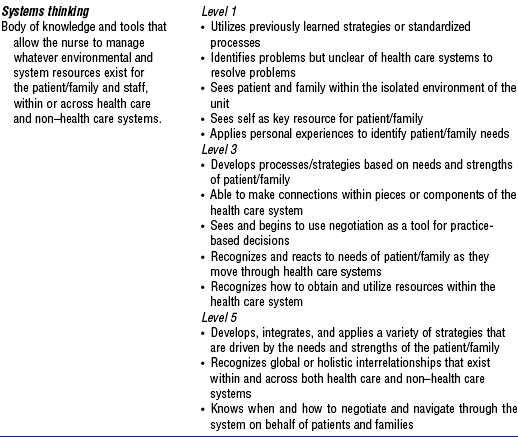

e. Systems thinking: The body of knowledge and tools that allow the nurse to manage whatever environmental and system resources exist for the patient, family, and staff within or across health care and non–health care systems

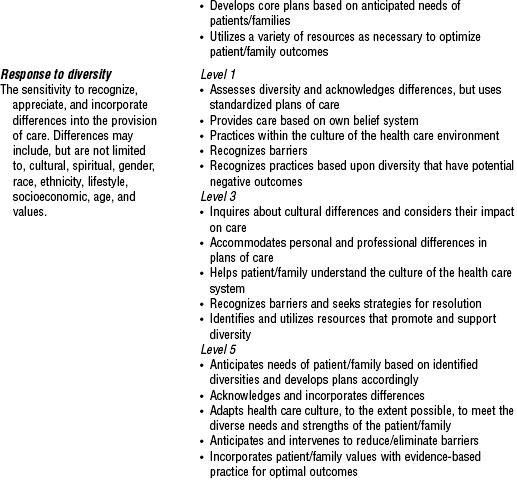

f. Response to diversity: The sensitivity to recognize, appreciate, and incorporate differences into the provision of care. Differences may include, but are not limited to, cultural, spiritual, gender, race, ethnicity, lifestyle, socioeconomic, age, and values.

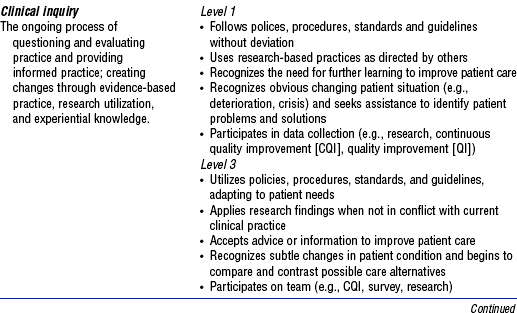

g. Clinical inquiry or innovation and evaluation: The ongoing process of questioning and evaluating practice and providing informed practice; creating changes through evidence-based practice, research utilization, and experiential knowledge

h. Facilitator of learning: The ability to facilitate learning for patients and families, nursing staff, other members of the health care team, and community; includes both formal and informal facilitation of learning

5. Outcomes of patient-nurse synergy (Figure 1-2) (Curley, 1998)

(From Curley M: Patient-nurse synergy: optimizing patients’ outcomes, Am J Crit Care 7:69, 1998.)

i. Behavior change: Based on the dispensing and receiving of information. Requires caregiver trust. Patients and families grow in their knowledge about health and take greater responsibility for their own health.

(a) Functional change and quality of life: Multidisciplinary measures that can be used across all populations of patients but provide specific information to a population of patients when analyzed separately

(b) Satisfaction ratings: Subjective measures of individual health and quality of health services. Satisfaction measures query about expectations (technical care provided, trusting relationships, and education experiences) and the extent to which they are met. Often linked with functional change and quality-of-life perceptions.

(c) Comfort ratings and perceptions: Quality-of-care outcomes based on caring practices with the aim of promoting comfort and alleviating suffering

i. Physiologic changes: Require monitoring and managing instantaneous therapies and noting changes. The nurse expects a specific trajectory of changes when he or she “knows” the patient (Tanner, Benner, and Chesla, 1993).

ii. The presence or absence of preventable complications: Through vigilance and clinical judgment, the nurse creates a safe and healing environment

iii. Extent to which care and treatment objectives were attained: Reflects the nurse’s role as an integrator of care that requires a high degree of collaboration

i. Recidivism: Decrease in rehospitalization or readmission, which adds to the personal and financial burden of care

ii. Cost and resource utilization: Organizations usually evaluate financial cost based on an episode of care. Achieving cost-effective care requires knowing the patient and providing continuity of care. Resource utilization can affect patient outcomes when there is not enough care given by competent nurses (Aiken et al, 2001). When nurses cannot provide care at an appropriate level to meet patient needs, they are dissatisfied and turnover is high, which results in increased costs for the organization (Cornerstone Communication Group, 2001).

Validation

1. National validation study methodology

a. Synergy Model originally validated in large-scale national study of practice (Muenzen and Greenberg, 1998)

b. Survey methodology used to determine predicted relationships among patient-family and nurse characteristics and their interactions in the Synergy Model

c. Surveys sent to 3924 nurses (adult, pediatric, and neonatal nurses in subacute, acute, and critical care settings); response rate of 24%

a. Respondents accurately perceived acuity of patients’ conditions in the profiles developed for the study

b. Respondents perceived that the critically ill patients described in the patient profiles required care by nurses with higher levels of the nurse characteristics listed in Table 1-2 than did the less acutely ill patients described in the profiles; respondents perceived that “clinical judgment” was most strongly related to patient need and that the nurse requires a higher level of this characteristic to achieve optimal outcomes

c. The eight patient characteristics and their associated rating scales were useful in differentiating acuity levels

d. Acuity-of-care levels were not differentiated based on the patient’s and family’s ability to participate in decision making and care, and the patient’s and family’s level of technical, fiscal, personal and psychologic, and social resources

e. Patients whose care requires critical care skills are not found solely in critical care units. They may be located in progressive care units, postanesthesia units, rehabilitation facilities, and the home environment.

f. The eight patient characteristics fall into two groups: Intrinsic (resiliency, vulnerability, stability, complexity, and predictability) and extrinsic (participation in decision making, participation in care, and resource availability)

g. The eight nurse characteristics are all intercorrelated and may reflect overall nurse competency

Application of the Synergy Model

There are many applications for the model in clinical operations, clinical practice, education, and research*

a. Leadership: Using the model for organizational infrastructure for achieving excellence in practice, improving financial outcomes, and establishing clinical advancement programs (Cohen et al, 2002; Czerwinski, Blastic, and Rice, 1999; Doble et al, 2000; Kerfoot, 2001)

b. Development of continuity-of-care models (Ecklund, 2002; Edwards, 1999)

c. Foundation model for family-centered care practice (Collopy, 1999; Henneman and Cardin, 2002; Stannard, 1999)

d. Basis for making care assignments and making nursing rounds (Hartigan, 2000; Mullen, 2002)

a. Development of clinical strategies (Markey, 2001)

b. Direct patient care (Annis, 2002; Hardin and Hussey, 2003)

a. Curricula design: Serves as the basis for the graduate nursing program curriculum at Duquesne University†

b. Basis for CCRN (critical care nurse) and CCNS (critical care clinical nurse specialist) certification examinations since 1999 (Moloney-Harmon, 1999)

c. Potential use as a foundation for education of health care teams (Molter, 1997)

a. Validated in the AACN Certification Corporation Study of Practice (1998, 2004)

b. Underwent theoretical review (Sechrist, Berlin, and Biel, 2000)

c. Further research needed related to consumer perspective, staffing and productivity implications for nursing, patient outcomes measurement, and development of a quantitative tool based on the model for rapidly assessing patients and determining nursing characteristics needed

GENERAL LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS RELEVANT TO CRITICAL CARE NURSING PRACTICE

Scope of Practice

Provides guidance for acceptable nursing roles and practices, which vary from state to state

1. Nurses are expected to follow the nurse practice act and not deviate from usual nursing activities

2. Advanced nursing practice: Expanded roles for nurses include nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, certified registered nurse anesthetist, and certified nurse-midwife. These roles require education beyond the basic nurse education and usually involve a master’s degree. Certain responsibilities associated with these roles are not interchangeable (ANA, 1997)

3. A scope of practice and standards for the acute care nurse practitioner was developed by AACN and the ANA

4. A scope of practice and standards for the acute care clinical nurse specialist based on the Synergy Model was published by AACN (Bell, 2002)

Standards of Care

1. A standard of care is any established measure of extent, quality, quantity, or value; an agreed-upon level of performance or a degree of excellence of care that is established

2. Standards are established by usual and customary practice, institutional guidelines, association guidelines, and legal precedent

3. Standards of care, standards of practice, policies, procedures, and performance criteria all establish an agreed-upon level of performance or degree of excellence

a. AACN standards for acute and critical care nursing practice (Medina, 2000)

d. ANA standards: The ANA has generic standards and also specialty standards (e.g., for medical-surgical nursing)

c. Standards of clinical practice for acute care certified nurse practitioners

d. AACN Scope of Practice and Standards of Professional Performance for the Acute and Critical Care Clinical Nurse Specialist (Bell, 2002)

4. National facility standards: Include those published by JCAHO and the National Committee for Quality Assurance*

5. Community and regional standards: Standards prevalent in certain areas of the country or in specific communities

6. Hospital and medical center standards: Standards developed by institutions for their staff and patients

7. Unit practice standards, policies, and protocols: Specific standards of care for specific groups or types of patients or specific procedures (e.g., insulin or massive blood transfusion protocols)

8. Precedent court cases: Standard of a “reasonable, prudent nurse” (i.e., what a reasonable, prudent nurse would have done in the given situation)

9. Other nursing and interdisciplinary specialty organization standards (such as those of the American Heart Association, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses)

Certification in a Specialty Area

1. Certification is a process by which a nongovernmental agency, using predetermined standards, validates an individual nurse’s qualification and knowledge for practice in a defined functional or clinical area of nursing

2. A common goal of specialty certification programs is to promote consumer protection and to promote high standards of practice

3. The certified nurse may be held to a higher standard of practice in the specialty than the noncertified nurse; certification validates the nurse’s knowledge and experience in a specialty area

4. Critical care certifications are awarded by AACN Certification Corporation, established in 1975. AACN Certification Corporation is accredited by the National Commission for Certifying Agencies, the accreditation arm of the National Organization for Competency Assurance

Professional Liability

1. Professional negligence: An unintentional act or omission; the failure to do what the reasonable, prudent nurse would do under similar circumstances, or an act or failure to act that leads to an injury of another. Six specific elements are necessary for professional negligence action and must be established by a person bringing a suit against a nurse (plaintiff) (Giordano, 2003; Guido, 1997):

a. Duty: To protect the patient from an unreasonable risk of harm

b. Breach of duty: Failure by a nurse to do what a reasonable, prudent nurse would do under the same or similar circumstances. The breach of duty is a failure to perform within the given standard of care. The standard defines the nurse’s duty to the patient.

c. Proximate cause: Proof that the harm caused was foreseeable and that the person injured was foreseeably a victim. This element can determine the extent of damages for which a nurse may be held liable.

e. Direct cause of injury: Proof that the nurse’s conduct was the cause of or contributed to the injury to the patient

f. Damages: Proof of actual loss, damage, pain, or suffering caused by the nurse’s conduct

2. Malpractice: A specific type of negligence that takes account of the status of the caregiver as well as the standard of care (Giordano, 2003; Guido, 1997). Professional negligence is malpractice. It is differentiated from ordinary negligence (e.g., failure to clean up water from the floor).

a. Professional misconduct, improper discharge of professional duties, or a failure by a professional to meet the standard of care that results in harm to another person

b. Malpractice is the failure of a professional person to act in accordance with prevailing professional standards or a failure to foresee consequences that a professional person who has the necessary skills and education would foresee

c. Most common types of malpractice or negligence in critical care settings include medication errors, failure to prevent patient falls, failure to assess changes in clinical status, and failure to notify the primary provider of changes in patient status

a. Definitions (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 1995)

i. Delegation: Transferring to a competent individual the authority to perform a selected nursing task in a selected situation; the nurse retains accountability for the delegation

ii. Accountability: Being responsible and answerable for actions or inactions of self or others in the context of delegation

iii. Authority: Deemed present when a registered nurse (RN) has been given the right to delegate based on the state nurse practice act and also has the official power from an agency to delegate

iv. Unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP): Any unlicensed personnel, regardless of title, to whom nursing tasks are delegated

v. Delegator: The person making the delegation

vi. Delegatee: The person receiving the delegation

vii. Competent: Demonstrating the knowledge and skill, through education and experience, to perform the delegated task

b. The five “rights” of delegation

i. Right task: The RN ensures that the task to be delegated is appropriate to be delegated for that specific patient. Example: Delegating suctioning of a tracheostomy in a stable patient to a licensed practical nurse is appropriate. If the patient is a head injury patient who becomes bradycardic and hypotensive during suctioning, then delegation of this task for this patient may not be appropriate.

ii. Right circumstances: The RN ensures that the setting is appropriate and that resources are available for successful completion of the delegated task

iii. Right person: The RN delegates the right task to the right person to be performed on the right person

iv. Right direction and communication: The delegating nurse provides a clear explanation of the task and expected outcomes; the RN sets limits and expectations for performance of the task

v. Right supervision: The RN does appropriate monitoring and evaluation, and intervenes as needed; the RN provides feedback to the delegatee and establishes parameters for receiving feedback about the outcome of the task

c. Model of the delegation decision-making process: The nurse must ensure that delegation of nursing tasks is based on appropriate assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation. Box 1-1 describes the model for delegation established by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing.

d. Nurse executives must ensure the following:

i. Policies and procedures concerning supervision and delegation are in place and are consistent with state nurse practice acts

ii. Job descriptions for UAPs do not include responsibilities for whose performance a license is required

iii. Adequate training and consistent orientation for UAPs are provided

e. In the complex critical care environment, many of the concepts for delegation to UAPs can also be applied to delegation of care to other professional nurses and licensed practical or vocational nurses (through assignments made by charge nurses or nurse managers)

i. The job descriptions and scope of practice for personnel with various levels of expertise and for various roles must be clearly defined

ii. When assignments are made, the patient’s characteristics (as defined by the Synergy Model) and required care procedures guide the decision regarding the competency level of the nurse who should provide the care

iii. Nurse executives and nurse managers must ensure that nurses have demonstrated and documented levels of expertise necessary to provide the care required by specific patients

iv. Additional training and experience are required for performance of many of the complex therapies needed by vulnerable critically ill patients

a. Staffing is a process and an outcome. The term can refer to the process by which human resources are used within a nursing care unit or to the number of staff members required to provide care. The individuals managing health care services have ethical responsibilities to ensure that policies and processes are in place to ensure the safety of the patients and the staff (Box 1-2) (Curtin, 2002a, 2002b).

b. The optimal use of RN time and expertise depends on a number of variables: allocating acute and critical care beds based on patient need; ensuring availability of adequate numbers of qualified, competent nursing and support staff; establishing sufficient support systems; following and adhering to legal and regulatory requirements; and evaluating services through outcome and quality measures

c. Patient and family–focused care requires matching the right caregiver to each patient, identifying systems that provided the right support in delivering care, incorporating legal and regulatory considerations, and measuring the outcomes of care

d. AACN (2000) recommendations for staffing policy include the following:

i. Develop a comprehensive strategic plan that links patient and family needs, cost of delivery, competency of providers, and staff mix with patient outcomes. Such a plan is required by the JCAHO standards. The plan must be flexible to adjust staffing to the unpredictability of increasing patient acuity in the critical care setting. It is difficult to state a single national staffing ratio or mix because staffing must be adjusted to meet the needs of a specific group of patients at a given time.

ii. The foundation for minimum staffing levels is clearly articulated in standards for acute and critical care nursing practice that prescribe a competent level of nursing practice, as well as in standards of professional performance that articulate the roles and behaviors of nursing professionals

Documentation

1. Mandates of regulatory agencies

a. Federal requirements: Related to narcotics, controlled substances, organ transplantation

b. National voluntary requirements: JCAHO’s requirements related to quality improvement activities

c. State requirements: May exist in specific situations (e.g., in relation to minors)

d. Community (regional or local) standards: May include enhanced documentation in specific areas of practice (e.g., epidural medication)

e. Hospital, medical center, or health maintenance organization requirements

2. Purposes of nursing care documentation in the patient record

a. To provide clear and concise communication between providers

b. To facilitate planning and evaluation of care, and demonstrate use of the nursing process

c. To show progress of patient treatment, changes in condition, and continuity of care, and to record patient status, appearance, and behavior

d. To protect the patient; the medical record may be used in litigation

e. To protect health care professionals and institutions, and reduce risk for possible litigation

a. General requirements regarding patient records

i. Should contain accurate, factual observations

ii. Should include times, dates, and signatures for notations and events entered

iii. Reflects patient status and unusual events

iv. Should reflect documentation of the nursing process on a continuing basis throughout the hospitalization

v. Should note omissions of care and rationale

vi. Should show that the physician was informed of unusual or adverse situations and record the nature of the physician’s response

vii. Should note deviations from standard hospital practice and the rationale for such deviations

ix. Should carefully document method of the patient’s admission, condition on admission, discharge planning, and condition on discharge

b. Specific JCAHO requirements regarding patient records

i. Patient’s name, address, date of birth, and name of any legally authorized representative

ii. Legal status of patient receiving mental health services

iii. Emergency care, if any, provided to the patient before arrival

iv. Findings of the patient assessment, including assessment of pain status, learning needs and barriers to learning, and cultural or religious needs that may affect care

v. Conclusions or impressions drawn from the medical history and physical examination

vi. Diagnosis or diagnostic impression

vii. Reasons for admission or treatment

viii. Goals of treatment and the treatment plan; evidence of interdisciplinary plan of care

ix. Evidence of known advance directives or documentation that information about advance directives was offered

x. Evidence of informed consent, when required by hospital policy

xi. Diagnostic and therapeutic orders, if any

xii. Records of all diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and all test results

xiii. Records of all operative and other invasive procedures performed, with acceptable disease and operative terminology that includes etiology, as appropriate

xiv. Progress notes made by the medical staff and other authorized persons

xv. All reassessments and any revisions of the treatment plan

xvi. Clinical observations and reports of patient’s response to care

xvii. Evidence of patient education

xix. Records of every medication ordered or prescribed for an inpatient

xx. Records of every medication dispensed to an ambulatory patient or an inpatient on discharge

xxi. Records of every dose of medication administered and any adverse drug reaction

xxii. All relevant diagnoses established during the course of care

xxiii. Any referrals and communications made to external or internal care providers and to community agencies

xxiv. Conclusions at termination of hospitalization

xxv. Discharge instructions to the patient and family

xxvi. Clinical discharge summaries, or a final progress note or transfer summary. Discharge summary contains reason for hospitalization, significant findings, procedures performed and treatment rendered, patient’s condition at discharge, and instructions to the patient and family, if any, including pain management plan.

Good Samaritan Laws

1. Various states have enacted laws to allow health care personnel and citizens trained in first aid to deliver needed emergency care without fear of incurring criminal and civil liability (Guido, 1997, pp. 103-104)

2. Laws vary among states; thus, nurses should be familiar with the relevant state law. Look for these elements when evaluating the state’s law:

3. Most laws require that care be given in good faith and that it be gratuitous

4. There is no legal duty to render care to strangers in distress

ETHICAL CLINICAL PRACTICE

Foundation of Ethical Nursing Practice

1. ANA Code of Ethics (ANA, 2001)

a. The foundation of ethical practice for nursing is the ANA Code of Ethics (Box 1-3). The ANA code is a statement of the ethical obligations and duties of every nurse, a nonnegotiable ethical standard for the profession, and an expression of the nursing profession’s commitment to society.

b. The preface to the ANA Code of Ethics states: “Ethics is an integral part of the foundation of nursing. Nursing has a distinguished history of concern for the welfare of the sick, injured, and vulnerable and for social justice. This concern is embodied in the provision of nursing care to individuals and the community. Nursing encompasses the prevention of illness, the alleviation of suffering, and the protection, promotion and restoration of health in the care of individuals, families, groups, and communities. Nurses act to change those aspects of social structures that detract from health and well-being. Individuals who become nurses are expected not only to adhere to the ideals and moral norms of the profession but also to embrace them as a part of what it means to be a nurse. The ethical tradition of nursing is self-reflective, enduring, and distinctive. A code of ethics makes explicit the primary goals, values and obligations of the profession.” (ANA, 2001)

2. AACN Ethic of Care (AACN, 2002): AACN’s mission, vision, and values are framed within an ethic of care and ethical principles. An ethic of care is a moral orientation that acknowledges the interrelatedness and interdependence of individuals, systems, and society. An ethic of care respects individual uniqueness, personal relationships, and the dynamic nature of life. Essential to an ethic of care are compassion, collaboration, accountability, and trust. Within the context of interrelationships of individuals and circumstances, traditional ethical principles provide a basis for deliberation and decision making. These ethical principles include the following:

a. Respect for persons: A moral obligation to honor the intrinsic worth and uniqueness of each person; to respect self-determination, diversity, and privacy

b. Beneficence: A moral obligation to promote good and prevent or remove harm; to promote the welfare, health, and safety of society and individuals in accordance with beliefs, values, preferences, and life goals

c. Justice: A moral obligation to be fair and promote equity, nondiscrimination, and the distribution of benefits and burdens based on needs and resources available; to advocate on another’s behalf when necessary

Emergence of Clinical Ethics

1. Definition of clinical ethics: “The systematic identification, analysis, and resolution of ethical problems associated with the care of particular patients” (Ahronheim, Moreno, and Zuckerman, 2001, p. 2)

a. Promote patient-centered decision making that honors the rights and interests of the patient

b. Facilitate the involvement of all clinicians (e.g., physicians, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals) who require assistance in this complex field

c. Promote organizational commitment as well as cooperation among all involved parties to implement plans on behalf of the patient

3. Foundation of clinical ethics (Jonsen, 1998)

a. Article by Shana Alexander (1962), “They Decided Who Lives, Who Dies”; described the work of a committee of ordinary citizens in Seattle, Washington, tasked with determining who would receive hemodialysis

b. Article in the New England Journal of Medicine by Duff and Campbell (1973) on ethical problems in the intensive care nursery; described the deliberate decision to withhold treatment from 43 babies with significant problems.

c. New Jersey Supreme Court decision in 1976 that allowed Karen Ann Quinlan’s family to withdraw medical treatment they believed she would not have wanted; laid the foundation for “ethics committees” (Cert denied, 1976)

d. Movement of bioethics out of the classroom into the clinical arena in the 1980s

e. Development in 1998 by the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities of core competencies recommended for all ethics consultants (Society for Health and Human Values–Society for Bioethics Consultation Task Force on Standards for Bioethics Consultation, 1998)

f. Progress in clinical ethics has been significant; however, many issues that have been evident for several years continue to be unresolved (Singer, Pellegrino, and Siegler, 2001)

4. Religion and clinical ethics (Ahronheim et al, 2001)

a. “Clinical ethics” now refers to secular bioethics

b. Religious leaders continue to play a role in the deliberation of moral and ethical dilemmas; often provide wisdom to secular community

c. Religious convictions of competent adults should be honored and respected (Brett and Jersild, 2003). This can be difficult for health care providers when it involves decision making by parents for dependent children.

d. Spiritual values (apart from religious beliefs) may affect health. Health care providers should be sensitive to the spirituality of their patients (Lynn and Harrold, 1999).

5. Cultural competence and clinical ethics: Cultural competence is the ability to identify the effects of a patient’s culture on the health of the patient (Ahronheim et al, 2001). The health care provider should use a framework of ethical decision making that factors in the patient’s culture while avoiding cultural stereotyping.

6. Organizational ethics and clinical ethics: Spencer et al (1999) define organizational ethics in terms of articulating, evaluating, and applying consistently the values of an organization as these are defined internally and externally. The mission of the organization should be consistent with the expectations of the employees. The health care provider’s ethical obligations supersede any organization’s processes or requirements (Ahronheim et al, 2001).

7. Ethics across the life span: Issues include the following (Ahronheim et al, 2001):

a. Before pregnancy: Carrier screening for genetic disorders; testing for human immunodeficiency virus; in vitro fertilization and related technologies; potential for human cloning; stem cell research; and surrogacy

b. During pregnancy: Manipulation of embryos; substance abuse during pregnancy; abortion; prenatal genetic diagnosis; implications of multiple births due to reproductive technologies

c. Infants: Treatment of infants born with severe impairments

d. Children and adolescents: Role in decision making

e. Elderly: Issues related to truth telling and confidentiality have shifted for this generation; planning with patient for potential lapses in decision making; emphasis on advance directives for this age group; end-of-life care issues

f. Caring for the family: Although the rights of the individual patient are still presumed to outweigh those of the family, this is being challenged in many situations and often leads to significant ethical conflicts. Conflicts center on autonomy and confidentiality. A philosophy of family-centered care has the potential to prevent such conflicts or reduce their effects on the care provided patients (Clarke et al, 2003; Curtis et al, 2001; Henneman and Cardin, 2002; Levine and Zuckerman, 1999; Levy and Carlet, 2002).

Standard Ethical Theory (Ahronheim et al, 2001)

a. Belief that actions are morally evaluated based on the extent to which they facilitate or promote happiness or well-being; health care providers’ actions often based on achieving a desired outcome or preoccupation with consequences of an intervention

b. Associated with English philosophers John Locke and John Stuart Mill

Ethical Principles (Ahronheim et al, 2001; Beauchamp and Childress, 2001; Stanton, 2003)

1. Patient autonomy and self-determination

a. Principle that a competent adult patient has the right to make his or her own health care decisions

b. Autonomy refers to the potential to be self-determining; clinically supported through the informed consent process, which facilitates decision making that is individualized based on the patient’s own values

c. Paternalism is the term used when health care providers make the decisions for the patient based on the rationale that it is in the patient’s best interest. This practice denies the patient the autonomy to make his or her own decisions.

a. Principle that the competent patient or appropriate surrogate is the best judge of the patient’s best interests

b. Source of common ethical conflicts when there are disagreements between physician and patient or surrogate. Conflict may arise between the physician’s perceived obligation to do good and obligation to respect the patient’s expressed wishes.

a. Principle that everyone fundamentally deserves equal respect

b. Point of reference for social policy related to access to health care

c. Distributive justice in health care usually involves how resources are allocated (e.g., scarcity of organs for donation, availability of intensive care unit [ICU] beds or health care staff, futility of care versus patient autonomy, cost-benefit ratio of treatments, and limiting of access to expensive treatments)

Common Ethical Distinctions

Should common ethical distinctions be used in clinical ethics assessments? According to Ahronheim et al (2001, pp. 51-56) there are four common distinctions used in clinical ethics discussions. These authors believe it is important to determine if these distinctions are logically valid (i.e., capable of sorting actions into two different groups without ambiguity) and morally relevant (i.e., one of the actions identified is morally justifiable whereas the other is not).

1. Active versus passive means to an end (or commission versus omission)

a. Often associated with euthanasia

b. Validity questioned because the decision to omit medical interventions to bring about a certain end often involves active behaviors (such as calling a meeting)

c. Involves serious moral issues similar to those in the distinction between “killing” and “letting die.” (For instance, it can be argued that it is justifiable to actively hasten a death if the alternative is to passively stand by while a patient suffers a prolonged death.)

d. Recommended not to use this distinction in clinical ethics assessments

2. Ordinary versus extraordinary means

a. Attempts to identify interventions based on whether they are standard of practice or not

b. Practice standards reflect what is being done, not necessarily what should or should not be done based on scientific principles. Should a patient be required to accept any kind of standard means of extending life even if properly grounded in science?

c. Not recommended as part of a clinical ethics assessment unless a patient adheres to a particular faith that prohibits a specific intervention(s)

a. “Killing” infers a deliberate and physically active process such as giving a lethal injection; “letting die” refers to letting the disease process take its course. No one has a moral obligation to rescue a person if the attempt would not prolong life or the attempt would put the rescuer at risk for significant harm.

b. The distinction appears to be valid and morally relevant but creates significant ethical dilemmas, especially in relation to assisted suicide

4. Withholding versus withdrawing

a. “Withholding” means never starting a given treatment; “withdrawing” means removing or stopping a treatment already started

b. Logical validity is questionable because there are only a few situations in which the distinction between the two actions is clear. There is no legal basis for the distinction.

c. No clear distinction in terms of moral relevance. Is it more justifiable not to intubate a patient than to extubate a patient when the end point is similar in both situations?

d. Despite the lack of logical validity and moral relevance, this distinction is commonly applied in clinical ethics

The Law in Clinical Ethics (Guido, 1997)

1. Informed consent for clinical care: Physicians or independent licensed practitioners have a separate duty to provide needed facts to a patient so that the patient can make an informed health care decision. The right to treat a patient is based on a contractual relationship grounded in mutual consent of the parties.

i. Expressed consent: Given directly by written or verbal words

ii. Implied consent: Presumed in emergency situations or implied by the patient’s behavior (such as presenting an arm to the practitioner to have blood drawn)

iii. Partial or complete consent: A patient may give consent for only part of a proposed therapy, for example, consenting to a breast biopsy but not to a mastectomy should it be needed

b. Elements of informed consent for clinical treatment

i. Explanation of treatment or procedure

ii. Name and qualifications of the person to perform the procedure and those of any assistants

iii. Explanation of significant risks (those that may lead to serious harm, including death)

iv. Explanation of alternative therapies to the procedure or treatment, including the risk of doing nothing at all

v. Explanation that the patient can refuse the treatment or procedure without having alternative care or support discontinued

vi. Explanation that the patient can still refuse the treatment or procedure even after it has started

c. Standards of informed consent disclosure

i. Medical community standard (reasonable medical practitioner standard): Disclosure of facts related to the treatment or procedure that a reasonable medical practitioner in a similar community would disclose

ii. Objective patient standard (prudent patient standard): Disclosure of risks and benefits based on what a prudent person in the given patient’s situation would deem material

iii. Subject patient standard (individual patient standard): Disclosure of facts relevant to a particular patient’s situation and what he or she would deem important to know to make an informed decision

iv. Medical disclosure laws: Requirement by some states that certain risks and consequences be printed on a consent form

v. Evolving standard proposed by Piper (1994, p. 310): Patient and physician determine together what informed consent means to them; patient must communicate his or her values and expectations of the procedure or treatment to the physician, ask questions and seek clarification of the physician-patient discussion, evaluate symptoms and report impressions of how well the treatment or procedure is working or worked, and make good-faith efforts to participate in the treatment

d. Exceptions to informed consent

i. Emergency situations: Consent is implied if there is no time for disclosure and informed consent

ii. Therapeutic privilege: Primary health care providers are allowed to withhold information that they feel would be detrimental to the patient’s health (i.e., likely to hinder or complicate necessary treatment, cause severe psychologic harm, or cause enough anxiety to make a rational decision by the patient impossible)

iii. Patient waiver: The patient may waive full disclosure while consenting to the procedure, but this cannot be suggested by the health care provider; the waiver must be initiated by the patient

iv. Prior patient knowledge: If the patient has had the same procedure previously and knows the risks and benefits as explained for the first procedure, then consent can be waived

e. Accountability for obtaining informed consent

i. The physician or independent practitioner has full accountability for obtaining informed consent

ii. A hospital is responsible for informed consent only if those obtaining the consent are employed by the hospital or if the hospital fails to take appropriate actions when informed consent was not obtained and the hospital is aware it was not obtained

iii. The nurse’s role in obtaining informed consent varies with the situation, institution, and state law

(a) Nurses should explain all nursing care procedures to patients and families. Such procedures rely on orally expressed consent or implied consent. If a patient refuses a procedure or care, this must be honored.

(b) Physicians can delegate the obtaining of informed consent to nurses. They do so at their own risk, but the nurse must ensure that all aspects of an informed consent are disclosed. Some hospitals do not allow nurses to obtain informed consent to limit the hospital’s liability.

(c) If a nurse has knowledge that an already signed consent form does not meet the criteria for informed consent or the patient revokes the consent, the nurse must notify the supervisor and/or physician

iv. To obtain blood at the request of law enforcement personnel without consent, five conditions must be present and documented (Guido, 1997, p, 130):

a. Blanket consent: Required prior to admission and covers routine and customary care

b. Specific consent forms: Often mandated by states; a detailed consent form with the following elements:

i. Signature of a competent patient or legally authorized representative; “competent” means that the patient has not been declared incompetent by a court of law and the person is able to understand the consequences of his or her actions

(a) The signature cannot be coerced

(b) The patient cannot be impaired due to medications previously received

ii. Name and description of procedure in lay language

iii. Description of risks and alternatives to treatment (including nontreatment)

iv. Description of probable consequences of proposed procedure

v. Signatures of one or two witnesses as mandated by state law; the witness is attesting that the patient actually signed the form

3. Informed consent in human research

a. Since 1974, the Department of Health and Human Services has required an institutional review board to approve protocols for human research*

b. Special precautions are in place to protect vulnerable patient populations such as minors, mentally disabled persons, children, and prisoners

c. Informed consent must include the following basic elements (Guido, 1997, pp. 131, 132):

i. A description of the purpose of the research, procedures that are experimental and those that are part of regular care, and expected duration of the subject’s participation

ii. The number of subjects to be enrolled in the study

iii. Description of foreseeable risks or discomforts

iv. Benefits, if any, to the subject

v. Disclosure of alternatives courses of treatment available

vi. Description of how confidentiality of information will be maintained

vii. Explanation of any compensation that will be provided and explanation of medical care that will be provided if injury occurs

viii. Contact information for further questions about the research and the subject’s rights as a research volunteer

ix. A clear statement that the subject understands that he or she is a volunteer and has not been coerced into participating; also a statement that the subject may withdraw consent to participate any time during the procedure without loss of benefits or penalties to which the subject is entitled

x. Language that is easy to understand and includes no exculpatory wording (such as that the researcher has no liability for the patient’s outcome)

xi. Notification of any additional cost that the subject may incur from participating in the research

4. Advance directive: A document in which a person gives directions in advance about medical care or designates who should make medical decisions if he or she should lose decision-making capacity

a. Living will: Generic term for an advance directive; some states do not recognize these

i. Not binding for medical practitioners

ii. Does not protect practitioner from criminal or civil liability

b. Natural death acts: Enacted by many states to protect practitioners from civil and criminal lawsuits and to ensure that the patient’s wishes are followed if the patient is not competent to make his or her own health care decisions.

i. A legally recognized living will

(a) Must be developed by a competent adult 18 years of age or older

(b) Must be witnessed by two persons; some states put restrictions on who can witness

(c) May be revoked by physically destroying, revoking in writing, or verbally rescinding

(d) Remains valid until revoked

(e) Becomes effective only when the person becomes qualified (i.e., is terminally ill or has an irreversible condition with loss of decision-making capacity). Usually two physicians must certify that procedures or treatments will not prevent death but merely prolong it

(f) Does not apply to medications and therapies given to prevent suffering and to provide comfort

c. Durable power of attorney for health care: Allows competent adults to designate someone to make their health care decisions for them if they become unable to make their own decisions

d. Medical or physician directive: Allowed in some states; lists a variety of treatments and procedures that the patient may want depending on the patient’s condition at the time he or she cannot make his or her own decisions; similar to a living will and with equal legal worth

e. Uniform Rights of the Terminally Ill Act: Adopted in 1980 and revised in 1989

i. Similar to natural death acts

ii. Narrow in scope and limited to treatment that is life prolonging in patients with a terminal or irreversible condition

iii. Patients who are in a persistent vegetative state are not qualified to use the provisions of this act

f. Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990

i. Mandates patient education about advance directives and provides assistance in executing such directives

ii. States that providers may not discriminate against a patient based on the presence or absence of an advance directive

g. Do-not-resuscitate (DNR) directives: Institution-based policies that allow patients and physicians to make a decision not to resuscitate in the event of cardiopulmonary arrest

i. Some states have out-of-hospital DNR laws that allow an individual to request not to be resuscitated by emergency personnel. These orders are still in effect for outpatient treatment, including emergency department care, unless revoked.

ii. Some hospitals do not recognize DNR orders during surgery. Others believe that the decision to resuscitate or not to resuscitate should be made together by the patient, the physician, and the anesthesiologist. Whatever decision is made should be clearly documented in the medical record prior to surgery.

a. World Medical Association Declaration on Death*

b. Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) guidelines developed by the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and in Biomedical and Behavioral Research state that “any individual who has sustained either irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem, is dead.”† Most states have adopted these guidelines.

c. Confusion and controversy still exist over the term brain death and the relation of such death to donorship for organ transplantation (Capron, 2001; Truog, 2003)

d. Procedural guidelines for the declaration of death

i. Triggering of a neurologic evaluation: As soon as the responsible physician has a reasonable suspicion that an irreversible loss of all brain functions has occurred, he or she should perform the appropriate tests and procedures to determine the patient’s neurologic status

ii. Obligation to declare a patient dead

(a) Cardiopulmonary criteria for determining death are recognized in all states. When the physician determines that the patient has experienced an irreversible cessation of cardiopulmonary functions, he or she declares the patient dead. Consent of the surrogate, family, or concerned friends is not required.

(b) Sensitivity to family or surrogate needs is required in declaring brain death. Family members have the option to obtain a second opinion about brain death.

iii. Cessation of treatment after a declaration of death: Once the declaration of death has been made, all treatment of the patient ordinarily should cease; exceptions to this might be when efforts are made to use the body or body parts for purposes stated in the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (education, research, advancement of medical or dental science, therapy, transplantation) or when the patient is pregnant and efforts are being made to save the life of the fetus

iv. In cases involving organ donation, health care professionals who make the declaration of death

(a) Should not be members of the organ transplantation team

(b) Should not be a member of the patient’s family

(c) Should not have malpractice charges pending against them that are related to the case

(d) Should not have any other special interest in declaration of the patient’s death (i.e., stand to inherit anything according to patient’s will)

a. World Medical Association Statement on Human Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation (World Medical Association, 2000)*

i. Tissue donor or living organ donor: Donor may be alive (e.g., bone marrow, kidney donor) or deceased (e.g., eye donor); organ donation by living donors poses special concerns due to the increased risk to donors’ lives (Benner, 2002)

ii. Heart-beating donor: Donor is brain dead but respiratory function is supported mechanically while cardiac function continues spontaneously

iii. Non–heart-beating donor: Organs are procured immediately after cessation of cardiorespiratory function

c. A recent study (Exley, White, and Martin, 2002) indicated that the following characteristics significantly influence the likelihood that families will make a decision to donate tissues or organs:

iii. Someone initiates discussion of donation: This person could be family member, physician, or organ procurement organization coordinator, but it is helpful to include the organ procurement organization coordinator early in the process

iv. Death caused by gunshot or suicide

v. Issuing of request before or during declaration of brain death

7. Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA)

a. A 1986 law requiring hospitals participating in Medicare to screen patients for emergency medical conditions and stabilize them or provide protected transfers for medical reasons (Center for Medicaid and State Operations, 2004; Frank, 2001)

b. Failure to adhere to the law results in large fines or loss of Medicare funding

c. Patients may sue hospitals in federal or state court for damages under EMTALA’s private right of action provision

a. Concept is an evolving standard (Ahronheim, 2001, pp. 72-74)

b. Definitions of futility lack consensus and are value laden, but futile care involves interventions that sustain life for prolonged periods even when there is no hope of improvement or achieving the goals of therapy (American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, 1999). Many questions remain unresolved and lead to ethical dilemmas and conflict.

i. Who establishes the goals of therapy? Is it the physician, the patient, the family, or all of them?

ii. What does the physician or hospital do if the medical decision is in conflict with that of the patient and family, who may have an unrealistic expectation for improvement (Curtis and Burt, 2003; Lofmark and Nilstun, 2002)?

c. The American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs (1999) recommends resolution of futility conflicts using a process-based framework

d. There is some evidence that bioethics consultation resulting in cessation of therapy shortens the length of therapy significantly (Rivera et al, 2001; Schneiderman, Gilmer, and Teetzel, 2000; Schneiderman et al, 2003)

9. Legal barriers to end-of-life care (Meisel et al, 2000)

a. The legal context of care affects interventions and outcomes

b. Legal myths and counteracting reality

i. Myth: Forgoing life-sustaining treatment for a patient without decision-making capacity requires evidence that this is the patient’s wish

ii. Myth: Withholding or withdrawing artificial nutrition or hydration from terminally ill or permanently unconscious patients is illegal

iii. Myth: Risk management personnel must be consulted before life-sustaining medical treatment can be stopped

iv. Myth: Advance directives must be developed using specific forms, are not transferable to other states, and govern all future decisions. Advance directives given orally are not enforceable.

Reality: Oral statements made by the patients may be legally valid directives. The patient does not have to be competent to revoke an advance directive but does have to be competent to make one. There are no specific forms required by any law to be used to document advance directives. Most states honor directives developed in other states.

v. Myth: Physicians will be criminally prosecuted if they prescribe high dosages of medication for palliative care (to relieve pain or discomfort symptoms) that result in death

vi. Myth: There are no legal options for easing suffering in a terminally ill patient whose suffering is overwhelming despite palliative care

Clinical Ethics Assessment

1. Identification of ethical issues and ethical decision-making models

a. Distinction between ethical and nonethical problems and dilemmas: Three characteristics must be present for a problem to be deemed an ethical one (Curtin as cited in Stanton, 2003):

i. The problem cannot be resolved with just empirical data

ii. The problem is inherently perplexing

iii. The result of the decision making will affect several areas of human concern

b. Elements of ethical decision-making models (Ahronheim et al, 2001; Stanton, 2003): There are many decision-making models. Common elements include the following actions:

i. Gather all data (including information from all the stakeholders) related to the issue

ii. Analyze and interpret the data: Is it an ethical issue versus a legal or policy issue? What ethical principles are involved? What ethical conflicts are present? What are the capabilities of the stakeholders involved?

iii. Identify courses of action and analyze the benefits and burdens of each course; project the consequences of the action

iv. Choose a plan of action and implement the plan; provide support to the stakeholders as needed

a. Conflicts between moral principles

b. Conflicts between interpretations of a patient’s best interest

c. Conflicts between moral principles and institutional policy or the law

3. Institutional ethics committees

a. Multidisciplinary team resource for patients and families, clinicians, and the institution

i. Assist with clarifying issues

ii. Assist with the development of institutional policies and procedures related to clinical ethical issues

b. Goals include promoting the rights of patients, fostering shared decision making between patients and clinicians, promoting fair policies and procedures that maximize the likelihood of good patient-centered outcomes; and enhancing the ethical practice of health care professionals and health care institutions

c. Educate staff and the community to achieve goals

d. Ethics consultation: The most common situations triggering consultations by physicians include the following (DuVal et al, 2001):

e. Composition: Should include representatives of all disciplines and of the institution administration, and community-at-large members

4. Ethics consultation: Process elements

a. Who has access to the process (all clinicians, patients, and/or families) should be delineated

b. Patients (or surrogates), if appropriate, and attending physicians should be notified (providing reason for the consultation, describing the process, and inviting participation)

c. Documentation should be in patient record or some other permanent record

d. Case review or process evaluation should be done to promote accountability

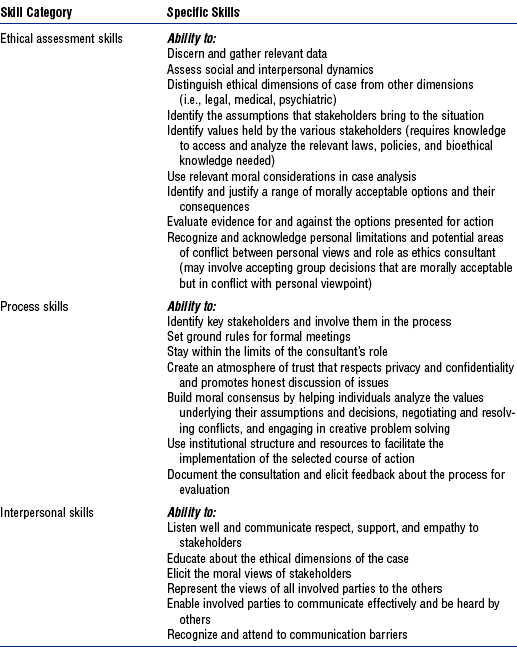

5. Core skills and knowledge required for effective ethics consultations (Society for Health and Human Values, 1998)

TABLE 1-3

Core Skills for Ethics Consultation

Adapted from Society for Health and Human Values–Society for Bioethics Consultation Task Force on Standards for Bioethics Consultation: Core competencies for health care ethics consultation, Glenview, Ill, 1998, American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, pp. 12-14. American Society for Bioethics and Humanities

i. Ethical assessment skills required to identify the nature of the ethical dilemma or conflict

ii. Process skills required to focus on efforts to resolve the ethical dilemma or conflict

iii. Interpersonal skills critical to the consultation process

i. Moral reasoning and ethical theory as it relates to consultation

ii. Bioethical issues and concepts that typically emerge in ethical consultations

iii. Health care systems as they relate to ethics consultation

iv. Clinical knowledge as related to the ethics consultation

v. Knowledge of the health care institution and institution policies in the context of the ethical consultation

vi. Beliefs and perspectives of the patient and staff populations served by the ethics consultation

vii. Relevant code of ethics, standards of professional conduct, and guidelines of accrediting organizations as they relate to ethics consultation

Nurse’s Role as Patient Advocate and Moral Agent

1. Organizational ethics and the nurse as patient advocate: AACN takes the position that the role of the critical care nurse includes being a patient advocate (AACN, 2003). The health care institution is instrumental in providing an environment in which patient advocacy is expected and supported. Patient advocacy is a fundamental nursing characteristic in the Synergy Model (Hayes, 2000). As a patient advocate, the critical care nurse does the following:

a. Respects and supports the right of the patient or the patient’s designated surrogate to autonomous, informed decision making

b. Intervenes when the best interest of the patient is in question

c. Helps the patient obtain necessary care

d. Respects the values, beliefs, and rights of the patient

e. Provides education and support to help the patient or the patient’s designated surrogate make decisions

f. Represents the patient in accordance with the patient’s choices

g. Supports the decisions of the patient or the patient’s designated surrogate or transfers care to an equally qualified critical care nurse

h. Intercedes for a patient who cannot speak for himself or herself in situations that require immediate action

i. Monitors and safeguards the quality of care the patient receives

j. Acts as liaison among the patient, the patient’s family, and health care professionals

a. American Hospital Association (AHA) Patient Bill of Rights (AHA, 1992); first published in 1973, revised in 1992; posted in all hospitals in the United States

b. Ethics of restraints: The use of restraints in critical care has the potential to violate several ethical principles (Reigle, 1996) and thus should be undertaken with caution

i. Nonmaleficence, or preventing harm; and beneficence, or doing good. Restraints are often used to prevent harm, but unintended consequences may violate this principle. The patient’s autonomy is breached, and restraints often cause significant physical harm. In many cases use of restraint does not prevent the disruption of medical therapy.

ii. Informed consent should be obtained from the patient and/or family prior to use of restraints. A discussion of alternative treatments should be included. A patient with decision-making capacity should be able to choose to forego restraint. Paternalism is involved in situations in which one overrides another’s decision to prevent harm to the person or maximize the benefits of treatment. There may be justifications for such actions in the critical care environment. If the patient lacks decision-making capacity and no surrogate decision maker is available, the nurse is obligated to use restraints to prevent significant or irreversible harm.

iii. Trust is important to the patient and family members. They trust nurses, and thus ongoing communication about restraint decisions is crucial. Family members become upset when the patient is restrained without their knowledge.

c. Ethics of pain management (American Pain Society Task Force on Pain, Symptoms and End of Life Care, n.d.; McCaffery and Pasero, 1999)

i. Patients have the right to have their reports of pain believed

ii. Patients have the right to have pain addressed appropriately

iii. Clinicians, patients, and families must be educated about pain treatment

iv. Pain and pain management must be made visible and emphasized in organizations

v. Policies on reimbursement for the services of health professionals, medications, and other palliative treatments must be designed so that they do not create barriers to symptom treatment

vi. Development of policies to ensure adequate treatment of symptoms should take precedence over legalization of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia

3. Family-centered care versus patient-centered care

a. Family members are not visitors (Molter, 2003)

b. The family has a vital role in supporting the patient through a critical illness (Simpson, 1991). When family members’ needs are not attended to or met, significant conflict occurs (Chesla and Stannard, 1997; Levine and Zuckerman, 1999).

c. Family-centered care focuses on the whole patient as a member of a family unit. It incorporates the family as a team member in the healing process. Improving family communications at the end of life can be cost effective for the family and institution (Aherns et al, 2003).

d. The family-centered care philosophy was developed by pediatric practitioners (Edelman, 1995). Box 1-4 summarizes the key tenets of the family-centered care philosophy. It is a collaborative approach to care and not a unilateral approach on the part of the clinicians or the family. It can be practically established in critical care units (Henneman and Cardin, 2002).

a. AACN organized a consortium to develop an agenda for the nursing profession on end-of-life care (EOLC) (Nursing Leadership Consortium on End-of-Life Care, 1999). Nine priorities were identified:

i. Education: Integrate EOLC into all curricula and develop interdisciplinary education on palliative care

ii. Professionalism: Create an environment for collaboration among health care systems, educational institutions, associations, and government agencies to meet the needs of EOLC

iii. Clinical and patient care: Establish practice guidelines that incorporate supportive strategies to prevent pain and suffering and promote comfort and well-being

iv. Research: Provide health care staff with research-based information on EOLC

v. Patient and family advocacy: Educate and empower the consumer of health care services about EOLC

vi. Decision making: Develop a dynamic process for making decisions about EOLC

vii. Culture: Create a national environment in which EOLC is freely discussed

viii. Systems of care: Structure a health care system that allows all dying patients and their families access to pain management and hospice care

ix. Resource allocation policy: Enact legislation that provides comprehensive financing for palliative care that is not limited to skilled nursing episodes or hospice care

b. Quality indicators for EOLC (Clarke et al, 2003, p. 2258). Consensus was established by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care End-of-Life Peer Workgroup. Seven domains were identified with specific indicators:

i. Patient and family–centered decision making

(a) Recognize the patient and family as the unit of care

(b) Assess the patient’s and family’s decision-making style and preferences

(c) Address conflicts in decision making within the family

(d) Assess, together with appropriate clinical consultants, the patient’s capacity to participate in decision making about treatment and document this assessment

(e) Initiate advance care planning with the patient and family

(f) Clarify and document the status of the patient’s advance directive

(g) Identify the health care proxy or surrogate decision maker

(h) Clarify and document resuscitation orders

(i) Assure the patient and family that decision making by the health care team will incorporate their preferences (Heyland et al, 2003)

(j) Follow ethical and legal guidelines for patients who lack both capacity and a surrogate decision maker

(k) Establish and document clear, realistic, and appropriate goals of care in consultation with the patient and family

(l) Help the patient and family assess the benefits and burdens of alternative treatment choices as the patient’s condition changes

(m) Forgo life-sustaining treatments in a way that ensures that patient and family preferences are elicited and respected

ii. Communication within the team and with patients and families

(a) Meet as an interdisciplinary team to discuss the patient’s condition, clarify goals of treatment, and identify the patient’s and family’s needs and preferences (Curtis et al, 2001)

(b) Address conflicts among the clinical team before meeting with the patient and/or family

(c) Use expert clinical, ethical, and spiritual consultants when appropriate

(d) Recognize the adaptations in communication strategy required for the patient and family depending on the chronic versus acute nature of illness, cultural and spiritual differences, and other influences