Chapter 4. Producing health

Tanya Claridge and Gary Cook

Introduction

This chapter discusses the characteristics and use of clinical pathways as commonly used tools in healthcare delivery to organise and manage, sometimes previously tacit, clinical processes into a more seamless and patient-oriented production system. Care is organised around clinical case types, for example patients with chronic obstructive airways disease; thus the ‘pull’ rather than the ‘push’ philosophy embodied within clinical pathways means that the production system is defined by the evidence-based needs and the expectations of the patient population instead of the ‘push’ from the healthcare system. Clinical pathways contribute to the production system by integrating low-tech patient-related activities with healthcare technology, information technology and social and management practices. Well-designed clinical pathways have the potential to reduce or eliminate wasted time, money and energy in healthcare, contributing to systems that produce safe, efficient, effective, and continuously improving and responsive healthcare.

From push to pull – moving from individual practitioner-based care to a co-produced service

Healthcare as a system

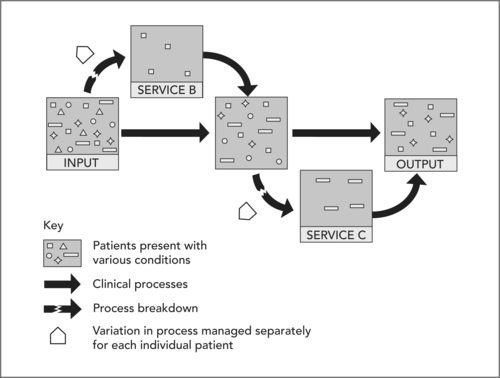

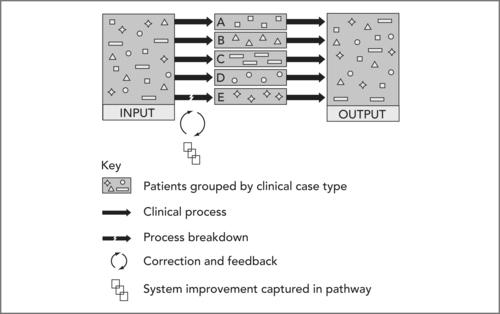

An evolution has occurred in the understanding of and emphasis given to the provision of healthcare. This evolutionary change shifts healthcare from an individually orientated pattern (with rudimentary batching and queuing of patients with different treatment needs grouped in ‘individual silos’) of delivery (see Figure 4.1), to one of a multidisciplinary systems-orientated pattern of patients grouped by similar conditions, treatments or healthcare needs (Figure 4.2). This evolution relates to the conceptualisation of healthcare as an industry comprised of complex systems and subsystems of healthcare organisation and delivery that incorporate dynamic and goal-orientated processes. In the first model, each different service manages a variation as if it were unique to each process and each (differently shaped) patient with little generalisation to similar patients or processes. In the second, variations are managed for populations of patients that stabilises the process, integrates the change and applies it to all subsequent patients treated for that particular case type (same shape).

In this context, healthcare delivery should be viewed as transdisciplinary and integrative. This conceptualisation of healthcare is underpinned by the assumption that reducing or removing a process from the whole system reduces the system’s overall effectiveness. This view stresses the interdependence between groups of individuals, structures and processes that enable the organisation to function and hence to result in a ‘co-produced’ service. Primacy is given to these interrelationships, and not, as with more traditional models of healthcare delivery (that centre on the effectiveness of individual practitioners, structures and departments), to the separate elements of the system.

All systems are determined by their inputs, outputs, processes, feedback and control mechanisms and environmental factors. This chapter explores how and why management of clinical processes within a healthcare system is needed to ‘produce health’, in terms both of improving process flow and of managing process variation.

Why manage clinical processes?

The development of organisational capability to deliver sustainable, accountable, patient-focused and quality-assured, safe healthcare is the aim of healthcare systems and organisations worldwide (Nicholls et al 2000, WHO 2000). However the context of healthcare delivery is complex and healthcare systems are subject to myriad pressures.These pressures include:

▪ changing patterns of supply and demand (Frankel et al 2000)

▪ the cost of innovation

▪ changing organisational structures

▪ patient and public expectations

▪ the diverse and complex nature of healthcare delivery.

At its simplest, clinical process management enables healthcare organisations to respond to these pressures by putting procedures in place to ensure individual practitioners/teams or services execute critical activities required to concurrently measure, improve or sustain the productivity, quality (Lilford et al 2007) and safety of care and guarantee a level of control to best manage and evaluate the system. Process management in any system can involve managing the ‘flow’, managing any variance in the process or both.

Managing process flow – lean thinking

The flow of work through healthcare systems is complex and costly, although the actual work involved is often routine. By delineating, standardising, synchronising and managing every step in the process of healthcare delivery, both in patient-focused systems and in wider networks of care (Keen et al 2006), the work can flow in line with actual demand. This is the premise of ‘lean thinking’. Lean thinking is not currently widely associated with healthcare organisations though the encouraging results produced in a variety of sectors all round the world have generated interest in the healthcare community (Institute of Health Care Improvement 2005). While the ideology was developed in Japanese manufacturing (Eisert 2006) it is just as applicable in healthcare, where waste (of time, money and supplies) is common, as it provides an opportunity to increase productivity, reduce waiting times, lower costs and improve services by improving processes.

Managing process variance – critical pathways

Critical Path Method (CPM) or Critical Path Analysis was developed in the 1950s for managing maintenance projects (DuPont Corporation and Remington Rand Corporation) and formalised within social science in the 1960s (Lucas 2001). It is now commonly used with many forms of projects that involve concurrent interdependent activities in diverse sectors including construction, research and engineering. CPM is essentially an algorithmic method for scheduling project activities. It produces, in diagrammatic form, the longest path of planned activities to the end of a project, the process of development determining both ‘critical activities’ and those that have ‘total float’ (i.e. can be delayed without making the project longer). Thus project managers can either prioritise actions to ensure the project is completed effectively, ‘fast track’ (by performing more activities concurrently) or direct resources (e.g. staff or equipment) to the critical path from activities that have ‘total float’. This is known as ‘crashing the critical path’.

Critical pathways are administrative models with close links to CPM, utilised in industry (Industrial Engineering 1992, Kallo 1996) as tools to improve the efficacy of production by streamlining work processes (Every et al 2000). Any variance on a production line in industry will have an effect on its efficacy. Using critical pathways to define and time processes enables the identification of problematic areas, the measurement of any variation and hence allows improvements to be made.

Identifying clinical processes

In order for clinical processes to be managed within the production systems of a health organisation they have to be identified. This is usually done by identifying the processes that support different ‘core services’. A core service of a healthcare organisation could be as generic as a patient appointment with a doctor. However if considered in the context of population-based healthcare, a core service of a healthcare organisation would be the provision of care for patients based on clinical case types. This approach to identifying ‘core population-based services’ of health organisations is just as relevant to primary care services as it is to secondary and tertiary care. Examples of some core services offered by healthcare organisations can be found in Table 4.1.

| Core product | Example |

|---|---|

| Assessment | of the psychosocial wellbeing of women in the early postnatal period (Yelland et al 2007) |

| Education | of caregivers of patients with dementia (Kazui et al 2004) |

| Surgery | Total joint replacement (Ho & Huo 2007, Saufl et al 2007) |

| Oesophagectomy (Low et al 2007) | |

| Prevention | of primary bacteraemia (Juan-Torres & Harbarth 2007) |

| Diagnosis and treatment | of septic arthiritis (Merino Muñoz et al 2007) |

| Support and signposting | of pregnant teenagers (Logsdon & Koniak-Griffin 2005) |

| Multidisciplinary identification and treatment | of distress in palliative care (Vitek et al 2007) |

| Public health | Preventive dental care (Tay et al 2006) |

| Management | of the technology-dependant child in the community (see example later in chapter) |

Pause for reflection

Healthcare economies are subject to multiple pressures including rapid technological advances, changing demographics and concerns about the quality and safety of the care received by patients. In response to these pressures there has been a shift from individual practitioner-led healthcare delivery to the co-production of care using a population-based systems approach that incorporates dynamic and goal-orientated processes. Process management techniques allow the management of flow, management of variance or management of both thus increasing standardisation and predictability within the system. Why is this important in managing healthcare?

Managing clinical processes – protocol-based care

Developing and implementing rules is one of the most common ways to manage behaviour in complex organisations (Hopwood 1974) to promote the uptake of clinical management practices. Promoting both quality and safety is one area of organisational behaviour in which rules feature heavily. For instance, Reason’s (1995) model of organisational safety indicates that rules, in the form of procedures, protocols and guidelines, are one of the principal defences necessary to ensure a safe organisation. In recent years there has been a proliferation of formal or semi-formal rules in healthcare worldwide, often in the form of policies, protocols, guidelines or clinical pathways in order to standardise and manage clinical processes both to improve the quality and measurability of healthcare systems and to try to ensure the safety of patients receiving care.

One of the key features of organised society is the development of a system of social rules and behavioural norms. The principal functions of such systems are to reflect societal and cultural values, and to safeguard things of value. Rules come in many different forms, including conventions, laws and social norms. Some are based on fundamental moral principles (it is wrong to commit murder), while others serve as a form of social control, proscribing antisocial behaviour (it is wrong to drop litter). Many rules exist purely in order to ensure that social affairs run smoothly. For example, driving on the right-hand side of the road is not intrinsically safer than driving on the left, but in many countries there is a rule (in this case, with the force of law) that all drivers will keep to the right. This rule has been imposed as a way of introducing standardisation and increasing predictability in a complex system.

Semi-formal and formal rules in various guises have been used for a number of years in all sectors of healthcare to regulate safety-critical ancillary processes (for instance storage of controlled and prescription drugs (Yee 1998) and hand washing (McCarthy et al 1999)). They have also been used with reference to clinical processes, for instance, guidelines on clinical technique and history taking are often presented in handbooks on clerking patients (Swash & Hutchinson 2001) and within the nursing process (Roper et al 1983). However, in recent years healthcare policy worldwide has begun to focus on the use of rules embodied in clinical pathways as a way of managing both quality and safety.

The implementation of evidence-based medicine (EBM), the doctrine that professional clinical practice should be based on sound research evidence (Sackett et al 2000), is one area in which rules governing clinical processes have been used as a vehicle for improving quality. Previously, even when clinical effectiveness was supported by apparently rigorous evidence, this proved insufficient to produce related changes in practice. For example, Schuster et al (1998) postulated that 30–40% of patients do not get treatment of proven effectiveness and 20–25% patients get care that is not needed or is potentially harmful. In response to the slow pace of progress towards evidence-based practice (EBP), policy interest increased in the use of rules to promote it (Grol 2001). For instance, the UK National Health Service (NHS) Plan (Department of Health 2000:86) specified that ‘by 2004 the majority of NHS staff will be working under agreed protocols’ and that there will be ‘a major drive to ensure that protocol-based care takes hold throughout the NHS’.

In terms of patient safety, there is also a move internationally towards using rules to regulate clinical processes and the behaviour of healthcare professionals (Kohn et al 2000). In 2002 the World Alliance for Patient Safety was formed and passed a resolution urging the World Health Organization to take the lead in developing global norms and standards. The assumption is that, as in other high-risk industries, patient safety can be improved by increasing standardisation and predictability in the system.

The drive for quality improvements, coupled with increased awareness of patient safety issues in recent years, has seen a proliferation of formal (active) or semi-formal (passive) rules, developed in order to standardise and manage the behaviour of healthcare professionals. The most common type of rule in healthcare is a protocol, which is essentially a set of instructions that can be formatted in a variety of different ways and used in many different clinical contexts.

Passive protocols (Coiera 2003) such as guidelines are semi-formal. They do not direct patient management, but provide guidance and add to the information resources available. Passive protocols are accessed or used at the discretion of the healthcare professional. In contrast, active or formal protocols (clinical pathways) are prescriptive, actively managing clinical processes. Active protocols are fundamentally different from passive protocols, in that they are central to the way the patient is managed, rather than an optional accessory. The way protocols are formatted also varies. Active protocols can be computer based and include alerts when there is deviation from the protocol (e.g. GP prescribing software). However, the majority of active protocols are paper based, allowing their effect on actual practice to be evaluated through audit of adherence and outcomes. Protocols in any format are seen by their exponents as ‘tools that ensure service development is driven by evidence of clinical or cost effectiveness, for improving the safety of and consistency of care, and for coordinating health services’ (Dillon & Hargadon 2003). In other words, protocols are tools that manage clinical processes within healthcare systems that should lead to improvements in the quality of care and in patient safety.

Managing clinical processes – clinical pathways

Clinical pathways (underpinned by an ideology similar to critical pathways described above) have been used worldwide (Hindle & Yazbeck 2005) for over a decade to systemise and support a process-centred vision of healthcare delivery. Clinical pathways have been variously known as anticipated recovery paths (ARPs), CareMaps®, multidisciplinary pathways of care (MPC), care protocols, integrated care management, pathways of care, care packages, collaborative care pathways, critical care pathways, care profiles and integrated care pathways. They are mass customisation disease- or symptom-specific case management plans that display goals for patients based on their clinical presentation and provide the sequence and timings of key elements of care based on EBM necessary to achieve these goals with optimal efficiency (Pearson et al 1995). They are generally conceptualised as vehicles for implementing collaboratively developed (multidisciplinary) care programs focused on population-based and patient-centred care. In theory fragmentation and duplication of care and treatment are therefore reduced, and coordination and communication are improved (De Bleser et al 2006, National Electronic Library for Health 2006).

Clinical pathways provide the opportunity to manage both clinical process flow and variance using lean thinking and critical pathway ideologies. They are developed by mapping and modelling clinical and non-clinical processes related to specific clinical case types or client groups. Opportunities for multidisciplinarity and skill mixing are identified based on roles, competencies and responsibilities rather than on individual disciplines alone. Both priorities and sequencing of actions are identified and processes and outcomes are incorporated (adapted from Venture Training 2005). The documentation – either paper or electronic – that supports the clinical pathway is designed to capture variations between the clinical processes planned and those experienced by the patient. The presence and implications of any variance can be analysed and assessed. Changes can then be made to the clinical process if necessary.

Clinical pathways and outcomes

Programs to develop and introduce clinical pathways aim to improve a range of clinical and financial parameters through decreased length of stay, preventing readmissions and reducing resource use (Vanounou et al 2007). There are few papers describing rigorous financial testing of clinical pathways. Those that are available tend to use algorithms to estimate savings based on the above objective process, throughput and outcome measures. Vanounou et al (2007) described a new model to evaluate the clinical and economic impact of clinical pathways. They used deviation-based cost modelling to determine the contribution of clinical pathway implementation itself to cost savings beyond usual secular trends in measuring improvements in care. The core product of the system involved in their study, a pancreaticoduodenectomy, was delivered using clinical processes that shortened length of stay, reduced resource use and decreased costs compared with before the clinical pathway was introduced. However, in a review of several case studies Lee & Anderson (2007) found that only one out of five clinical pathways implemented showed an association with a statistical significance in decreasing the length of stay. In another study an acute inpatient clinical pathway for psychosis and depression was trialled for a 12-month period and discontinued after it failed to demonstrate any improvement in terms of either clinical or financial parameters (Emmerson et al 2006). The authors suggested that the complexity, individuality and variability of mental disorders meant that clinical pathways were not beneficial in mental health settings.

It is difficult to establish whether or not all clinical pathways will have a direct impact on patient and/or financial outcomes. It may therefore be more important to explore the impact clinical pathways can have on clinical processes themselves. This involves ceasing dependence on inspecting clinical outcomes to achieve quality and eliminating the need for inspection on a mass basis by building quality into the process in the first place and monitoring the processes themselves (adapted from Deming 2000, Lilford et al 2007).

It is a natural assumption to make that a clinical pathway designed to delineate a pre-determined, evidence-based clinical process will have an effect on that process. It may also be reasonable to assume if the anticipated process is delivered to the expected standard then the desired outcomes will also be achieved. However, there are few tools available to assess how a clinical pathway influences clinical processes in the production of core healthcare services (Vanhaecht et al 2007). This may be due to a general lack of clarity about the concept of clinical pathways, but also related to the preoccupation of healthcare organisations with achieving financially motivated targets, for instance length of stay and readmissions. Vanhaecht et al (2007) have developed a care process self-evaluation tool designed to assess the organisation of the clinical processes embedded in an acute clinical pathway. The tool allows an assessment of the impact of a clinical pathway on clinical processes in terms of multiple domains including the coordination of care, cooperation with primary care and monitoring of the clinical process.

Clinical pathways are thus a potentially effective instrument in ensuring high-quality, effective and safe clinical processes because, in theory, they decrease process variability and improve process flow. This is because they are tools that can be used both at a macro level to delineate system design and integration and at a micro level to influence and regulate the behaviour of healthcare professionals at the patient care interface. The role of clinical pathways in ensuring effective clinical processes at these different levels of a system is discussed in more detail below.

Influencing system design – supporting patient focus and coordination of care

Developing a clinical pathway requires mapping the current state of the process critical to the delivery of the ‘core service’ under scrutiny (Hunter & Segrott 2007). This is often where ‘lean thinking’ can facilitate changes in the process to place the patient at the centre and to better coordinate care, removing unnecessary steps, even before the clinical pathway has been produced. Consider the case study in Box 4.1 and the diagrammatic representation in Figure 4.3.

Box 4.1

In the UK, care and support for technology-dependent school-age children living at home and their carers is delivered by both multiple provider services operating within primary care trusts (e.g. health visiting, nutrition and dietetics, school nursing, equipment and adaptations) and external agencies (e.g. secondary care, tertiary care, social care and hospices). One of the core services required for this patient population is the needs assessment and provision of specialist equipment (for instance enteral feeding, airway management and continence supplies). Complaints from relatives of technology-dependent children and anecdotal information from healthcare professionals highlighted both the complexity and lack of accountability within the system. Mapping of the clinical and non-clinical processes for this core service revealed that time and resources were wasted on non-clinical processes and there was a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities of practitioners within the system. Box 4.4 contains a diagrammatic representation of this original individual practitioner-led ‘push’ system. The time taken for new equipment to be ordered could take up to a month, causing potential delays to patient discharge from secondary care and distress and frustration to both the family of the patients and the healthcare professionals involved.

In the diagram above, it is clear that the clinical processes involved are complicated and dependent on a health visitor to assess (registered general nurse with an additional specialist community practitioner/public health qualification) even though the visitor has no day-to-day contact with the child (in the UK health visitors manage the child health surveillance and safeguarding of preschool children). The health visitor, with little or no expertise in the care of a technology-dependent child, has to consult with numerous other professionals and administrators. The health visitor also has no control over the equipment budget from which the cost of the order has to be met. Any order has to be agreed with senior managers and the finance department. Primary care trusts in the UK are divided into departments with a commissioning function and multiple discrete provider units (shaded boxes). There are few established communication systems and there is no clarity as to which provider unit should be commissioned to fund and provide the equipment for the child. Now consider the same process organised using a pathway approach in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4 shows a visual representation of how the clinical and non-clinical processes could be refined by removing unnecessary steps and defining the ‘critical path’ essential to produce the core service. Delineating and structuring the clinical processes within a clinical pathway can facilitate the delegation of decision making about the provision of equipment to both healthcare professionals involved with the family and the family itself.

This case study provides examples of how managing clinical processes supported by a clinical pathway can rationalise systems of healthcare delivery, facilitate the involvement of patients/carers in decision making despite the population-based approach (Edwards & Elwyn 2001) and promote multidisciplinarity to ensure any service is co-produced.

Influencing system design – promoting multidisciplinarity

From the early 1980s it has been recognised that the complexity and demands of many tasks and decisions in healthcare are often too great for any individual to conceptualise and manage (Kahneman et al 1982). For this reason multidisciplinary teamworking is central to the performance of healthcare systems. Because of their ability to process large amounts of information, teams of healthcare professionals comprising members with different areas of expertise, skills and knowledge are now ubiquitous in medical contexts. However teams of healthcare professionals tend to be hierarchical with distributed expertise as well as distinguishing characteristics (Phillips 2001). Distributed expertise refers to the fact that team members differ in the type of information and expertise they contribute to the clinical process. Status differences can exist among the team members and decision responsibility may be distributed unequally among them.

The co-production of healthcare services from healthcare systems (i.e. those produced through transdisciplinary integrative clinical processes) is a goal that is therefore not easy to achieve in a healthcare context. There are numerous barriers to the changes needed to ensure optimum teamworking, ranging from clashes of personalities to occupational structures. Further, the way in which health professions are organised as vertical hierarchies is one of the barriers to effective teamworking (Mackay 1993). Professional boundaries can become barriers to innovation (Walby et al 1994) and they can also become a refuge when collaboration is difficult to achieve (Greenwell 1995).

Meta-analysis of participative decision making has shown that participation is generally related to greater satisfaction, motivation and task performance (Wagner & Gooding 1987) although some studies in the US have shown a fairly strong negative relationship (Phillips 2001). Phillips suggested that the mixed findings regarding the effectiveness of collaborative decision making may be due to the lack of attention paid to team performance in general. Effective collaboration between professional staff has long been recognised as essential to maximising possible health gain (Greenwell 1995) and is therefore axiomatic in enhancing the effectiveness of healthcare systems.

Mapping clinical processes illustrates the interactive and dynamic nature of healthcare systems. It is clear that to improve multidisciplinary collaboration, communication systems must play a central part in co-producing core services. These communication systems are diverse and include multiple, disparate non-electronic technologies (charts, telephones, patient records) and electronic technologies (electronic prescriptions, pathology reporting systems). Accurate and effective communication within and between services and professional teams involved in a clinical process is essential to achieving both efficiency and effectiveness.

Communimetric tools (Lyons 2006) are specifically designed to communicate the clinical process between healthcare professionals of different clinical backgrounds and allow the use of technology to support improved care. Introducing the electronic patient records is an international preoccupation that aims to facilitate this process of communication. However, a conceptual and representational view of the processes needs to be developed in order to fully understand existing clinical processes (Berg 1999) before such tools can be integrated into the clinical processes related to producing core health services. Healthcare systems are inherently complex and developing clinical pathways can contribute to this conceptual view by providing a multidisciplinary-representational model of low-tech patient-related activities integrated with healthcare technology, information technology, social conventions and management practices.

Influencing system design – clinical process monitoring

The analysis of valid criteria within clinical processes (derived from information contained within clinical pathways) can provide a sensitive, useful and cost-effective method of monitoring the quality of the system of healthcare delivery. Lilford et al (2007) identify four advantages that process measures have over outcome measures. These are:

1. the reduction of casemix bias by using the opportunity for clinical process error as the denominator (which is heightened with sicker patients) rather than number of patients being treated (Lilford et al 2007)

2. the focus on improving steps within clinical processes rather than labelling systems as failures; for instance, Read & Levy (2006) describe clinically important, positive impacts on clinical processes related to the assessment and care of patients who had suffered a stroke as a result of the implementation of a clinical pathway irrespective of whether those impacts affected outcomes such as mortality or length of stay

3. the multidisciplinarity of clinical processes and clinical pathways that result in applying multidisciplinary solutions to any problems, in turn resulting in wider action within the system; for example, Wolff et al (2004) used the assessment of compliance with key process measures, determined as best practice in stroke care to conclude that significant improvements in the quality of patient care could be made by incorporating multidisciplinary reminders and checklists about relevant clinical processes in a clinical pathway

4. clinical process monitoring that can contribute to the root cause analysis of delayed adverse events.

The findings of ongoing clinical process monitoring should also be able to contribute directly to, and provide structure for, risk management and other clinical governance activities within healthcare systems, enabling organisations to be ‘scanning the horizon’ for potential risks and deal with them in a proactive way (Kirk et al 2007).

Pause for reflection

Managing population-based clinical processes and developing clinical pathways are central to the planning, development and monitoring of healthcare, but also to delivering safe, effective care at the patient care interface.

While the actual mapping of clinical processes and the development of related clinical pathways may promote multidisciplinary working by creating an inclusive collaborative environment for developing healthcare systems and an opportunity to monitor the quality of care received by patients, unless the clinical pathways are used as they are designed the multidisciplinary working and the integrity of the clinical processes they support will not be sustained.

Why is it not sufficient to consider the co-production of health through healthcare systems (underpinned by clinical processes and supported by clinical pathways) purely in terms of the systems and system artefacts? Why is it essential to explore the potential impact of clinical pathways at a micro level (at the patient care interface)?

Managing clinical processes and provider behaviour

Most clinical care occurs within the context of the patient–provider interface and any effects of clinical process management are mediated through this interface. Provider behaviour is therefore one of the most proximal determinants of whether the clinical processes delineated in the clinical pathway are translated into practice. In order to develop a better theoretical understanding of professional behaviour it is essential to explore determinants of provider behaviour to better identify both modifiable and non-modifiable factors (Claridge 2006).

The presence of clinical pathways to manage clinical processes and to promote quality and safety in healthcare is not enough to ensure the quality and safety of care provided. Clinical pathways are essentially rules designed to influence and control behaviour. In order to have an effect the rules have to be followed. It is crucial that they are both understood and accepted by those expected to use them. It is also important to know whether the widespread non-compliance with guidelines that has been noted (Grol et al 1998) is the result of genuine error or of deliberate decisions on the part of the individual. This distinction between mistaken non-compliance (error) and deliberate non-compliance (violation) has been shown to be crucial in other contexts (Parker et al 1995) as they require different remediation.

Classifications of the determinants of rule-related behaviour have been developed and studied in a variety of settings, including driver behaviour (Parker et al 1995), in organisational terms (Reason et al 1998), in healthcare (Parker & Lawton 2003) and in communication (Shimanoff 1980) and are often closely related to theoretical considerations and investigation of human error. While a number of taxonomies of rule-related behaviour have been developed in diverse settings, striking similarities are evident. All include some element of deviation (Reason 2000, Senders & Moray 1991), although rule-related behaviour is generally seen as being controllable (Parker et al 1995, Shimanoff 1980) in that the agent is responsible for the behaviour and can either perform the behaviour or not. It is also often seen as criticisable (Parker et al 1995, Reason 2000, Shimanoff 1980). Evidence that supports the criticisability of the behaviour can be found in judgments of appropriateness, negative sanctions and repairs of deviations (Shimanoff 1980). Rule-related behaviour is therefore contextual, part of a behavioural pattern and connected with particular situations. Reason et al (1995) outline a way of classifying rule-related behaviour that focuses on ways in which people behave in relation to procedures, and on the outcome of such behaviour in terms of achievement of goals based on research into driving errors, driver violations and accident involvement (Parker et al 1995).

Unintentional non-compliant behaviour (error)

Human error has been defined as ‘the failure of planned actions to achieve their desired outcome without the intervention of chance or unforeseeable agency’ (Parker et al 1995:1036). Errors in healthcare have been described as ‘the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended; or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim’ (Kohn et al 2000:1). These definitions of human error allow a separation of two distinct types of error, namely:

▪ Slips or lapses that occur when the plan is adequate but the associated actions do not go as intended, i.e. they are skill based, and are thus failures of execution. Slips can be seen as relating to observable actions and can be correlated to attention failures. Lapses are internal events and relate to failures of memory (Reason 2000). An example of these errors could be connecting oxygen tubing to IV tubing or forgetting essential details of a patient’s treatment at shift handover.

▪ Failures of intention (mistakes) that occur when the actions may go entirely as planned but the plan is inadequate to achieve its intended outcome, a rule is applied incorrectly or the actions do not achieve the intended outcome due to knowledge deficits.

Mistakes can be subdivided into rule-based mistakes and knowledge-based mistakes (Reason 2000). The implications here are that the failure occurs at a higher level in terms of the mental processes involved in an action, that is, the development, implementation and evaluation. Rule-based mistakes can occur when a person has some sort of pre-packaged solution to an issue, for instance in terms of training or guidelines. This gives rise to the error occurring in various forms such as the misapplication of a good rule (in the wrong circumstance), the application of a bad rule or the non-application of a good rule (Reason 1990). On the other hand, knowledge-based mistakes occur in novel situations where the solution has to be developed on the spot.

Reason 2000 reduced error-producing conditions to eight broad categories:

1. high workload

2. inadequate knowledge

3. ability or experience

4. poor interface design

5. inadequate supervision or instruction

6. stressful environment

7. mental state

8. change (major factor in absentminded slips of action) (Reason & Mycielska 1982).

Intentional non-compliant behaviour (violations)

Clinical pathways introduce procedures to regulate behaviour. Procedures introduced for this reason can give rise to a type of behaviour that is very difficult to deal with in terms of managing risk in healthcare systems or any other organisation, that is, the intentional deviation from procedures or procedural violation (Free 1994, Reason 2000, Lawton & Parker 1998).

Violations fall into four main groups:

1. Routine violations – cutting corners whenever such opportunities present themselves. If staff are not ‘punished’ by the system (perhaps by a safety incident or peer disapproval) they become incorporated into the normal way of working. If rules are increased or made more restrictive in response to routine violations, a heightened opportunity for routine violations and their reward or reinforcement is created.

2. Optimising violations – occur for personal gain or to alleviate boredom.

3. Situational violations – occur when the rule cannot be carried out in the circumstances when it is expected to be used.

4. Exceptional violations – occur in exceptional circumstances, where time pressure or even emotion may prevent people from following even the most basic rules.

Violations are characterised as being a social phenomenon and as having a broad organisational context. Though the precise conditions in which they are promoted are not especially well understood, they are, however, generally associated with resistance to change and motivational problems (e.g. low morale, the failure to reward compliance or to sanction non-compliance) occurring in a regulated social context (Reason 2000).

Why is the distinction between error and violation important?

Until recently, in healthcare, the relevance of this distinction had not been explored in a systematic way (Claridge 2006). In a recent study Claridge (2006) encountered difficulty in establishing quantitatively a clear, consistent distinction between errors and violations. The concept of, and therefore the recognition of, a violation appeared to be relatively novel to healthcare professionals and their managers. Violations can only occur when known rules are in place to manage behaviour. In healthcare, there is a general preoccupation with error reduction, usually by increasing the layers of organisational defences (which include procedures, checking and electronic support) (Reason 2000), error reporting systems (for instance the National Reporting and Learning System (NPSA 2005)), where violations and errors are not distinguished or distinguishable, and identifying system factors contributing to adverse events (e.g. root cause analysis (NPSA 2005)). Claridge (2006) suggests that the management of rule violations in healthcare is a challenge that those involved with clinical process and risk management have not yet acknowledged. Violations are dangerous as they can bypass organisational defences, yet their impact on the performance of clinical processes and ultimately the safety of patients has not been assessed.

Research and development in high-risk industries (e.g. nuclear and petrochemical industries) provides useful information about factors that encourage violations (Battman & Klumb 1993, Hudson et al 1998, Williams 1997) and preferred actions to decrease violations (Hale et al 2003, Leplat 1998, Perin 1993). It is essential to apply this existing knowledge to the consideration of rule-related behaviour in clinical process management. This application should contribute directly to developing and implementing clinical process management in healthcare systems worldwide.

Conclusion

Clinical pathways can be used to organise and manage clinical processes related to specific ‘core services’ to structure a system of healthcare delivery that spans organisational and geographical boundaries. The patient trajectory through the system is pre-defined, risks are pre-assessed and monitored and waste is minimised. Clinical pathways seek to embed quality and safety assurance at the point of care delivery (micro context), while providing evidence for service planning, budgeting and sub-contracting (macro context). Acquired information through variance analysis can be used to identify causes of medical error, areas of high cost both in terms of the organisation and for the patient and also potentially to shape improvement or restructuring of clinical processes to manage costs and improve both quality and safety. Such improvements in resource use and reductions in poor outcomes and harm enhance the overall contribution of healthcare systems to the wider health of the community.

Crucially, clinical pathways need to be used by healthcare professionals at the patient care interface to be effective in the ways described above. The rule-related behaviour of healthcare professionals should be a central consideration when developing clinical pathways; clinical process management invariably involves change, sometimes at the expense of short-term goals or aspects of the process that professionals feel comfortable with. Change is one of the significant factors in an environment that make violations more likely. Clinical process management also imposes a structure on the delivery of healthcare. Claridge (2006) found that this structuralisation caused the most dissatisfaction among healthcare professionals with clinical pathways, compared with the evidence on which they were based and their appearance. This dissatisfaction could lead to intentional non-compliance with the clinical pathway at the patient care interface.

In healthcare organisations worldwide structures such as clinical governance, risk management and financial assurance and quality control are remote finite entities (Degeling 2006) and clinical process management is often indistinguishable from a collective of service development and improvement initiatives. In order for the status and function of clinical process management to be clear to healthcare professionals, these structures need to be embedded within clinical processes rather than distinct entities. For instance, a safety management system can be embedded within a healthcare system, expressed within clinical process management and clinical pathways. Therefore clinical processes that cut across disciplines or professional groups and that operate within and between different care settings and producing core services to diverse patient populations require a responsive integrated management infrastructure (Degeling 2006) (including governance/finance/risk) that supports all functions and features of the healthcare system, its component clinical processes and supporting clinical pathways.

References

Battman, W.; Klumb, P., Behavioural economics and compliance with safety regulations, Safety Science 16 (1) (1993) 35–46.

Berg, M., Patient care information systems and health care work: a sociotechnical approach, International Journal of Health Informatics (55) (1999) 87–101.

Coiera, E., Guide to Health Informatics. (2003) Hodder Arnold, London.

De Bleser, L.; Depreitere, R.; De Waele, K.; et al., Defining pathways, J Nurs Manag 14 (7) (2006) 553–563.

Degeling, P., Realising the developmental potential of Clinical Governance, Clin Chem Lab Med 44 (6) (2006) 688–691.

Deming, E., Out of the Crisis. (2000) MIT Press, USA.

Edwards, A.; Elwyn, G., Developing professional ability to involve patients in their care: pull or push?Quality in Health Care 10 (2001) 129–130.

Emmerson, B.; Frost, A.; Fawcett, L.; et al., Do clinical pathways really improve clinical performance in mental health settings?Australasia Psychiatry 14 (4) (2006) 395–398.

Every, N.R.; Hochman, J.; Becker, R.; et al., Critical pathways: a review. Committee on Acute Cardiac Care, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association, Circulation 101 (2000) 461–465.

Frankel, S.; Ebrahim, S.; Davey Smith, G., Education and debate. The limits to demand for health care Commentary: An open debate is not an admission of failure, BMJ 321 (2000) 40–45.

Free, R., The role of procedural violations in railway accidents. PhD thesis. (1994) University of Manchester.

Greenwell, J., Patients and Professionals, In: (Editors: Soothill, K.; Mackay, L.; Webb, C.) Interprofessional Relations in Healthcare (1995) Edward Arnold, London.

Hindle, D.; Yazbeck, A.M., Clinical pathways in 17 European Union countries: a purposive survey, Aust Health Review 29 (1) (2005) 94–104.

Ho, D.M.; Huo, M.H., Are critical pathways and implant standardization programs effective in reducing costs in total knee replacement operations?Journal of American College of Surgeons 205 (1) (2007) 97–100.

Hunter, B.; Segrott, J., Re-mapping client journeys and professional identities: A review of the literature on clinical pathways, International Journal of Medical Inform 76 (2–3) (2007) 151–156.

Industrial Engineering, Critical Path Software Smooths Road for Automotive Supplier, Industrial Engineering 24 (1992) 28–29.

Institute of Health Care Improvement, Going Lean in Health care. (2005) Institute of Health Care Improvement, Cambridge.

Kallo, G., The reliability of critical path method (CPM) techniques in the analysis and evaluation of delay claims, Cost Engineering 38 (1996) 35–37.

In: (Editors: Kahnemann, D.; Slovic, P.; Tversky, A.) Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (1982) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Kazui, H.; Hashimoto, M.; Nakano, Y.; et al., Effectiveness of a clinical pathway for the diagnosis and treatment of dementia and for the education of families, International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 19 (9) (2004) 892–897.

Keen, J.; Moore, J.; West, R., Pathways, networks and choice in health care. International, Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance 19 (4) (2006) 316–327.

Kirk, S.; Parker, D.; Claridge, T.; et al., Patient safety culture in primary care: developing a theoretical framework for practical use, Journal of Quality and Safety in Health Care 16 (2007) 313–320.

In: (Editors: Kohn, L.; Corrigan, J.; Donaldson, M.) To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America (2000) Institute of Medicine National Academy Press, Washington.

Lawton, R.L.; Parker, D., Procedures and the professional: The case of the British NHS, Risk Decision and Policy 3 (1998) 199–211.

Lee, K.H.; Anderson, Y.M., The association between clinical pathways and hospital length of stay: a case study, Journal of Medical Systems 31 (1) (2007) 79–83.

Leplat, J., About implementation of safety rules, Safety Science 29 (3) (1998) 189–204.

Lilford, R.; Brown, C.; Nicholl, J., Use of process measures to monitor the quality of clinical practice, British Medical Journal 335 (2007) 648–650.

Logsdon, M.C.; Koniak-Griffin, D., Social support in postpartum adolescents: guidelines for nursing assessments and interventions, Journal of Obstetric Gynecological and Neonatal Nursing 34 (6) (2005) 761–768.

McCarthy, G.M.; Koval, J.J.; MacDonald, J.K., Compliance with recommended infection control procedures among Canadian dentists: results of a national survey, American Journal of Infection Control 5 (1999) 377–384.

Mackay, A., Team up for excellence. (1993) Oxford Press, New York.

Nicholls, S.; Cullen, R.; O’Neill, S.; Halligan, A., Clinical Governance its origins and its foundations, Clinical Performance and Quality Health Care 8 (3) (2000) 172–178.

Parker, D.; Lawton, R.L., Psychological contribution to the understanding of adverse events in health care, Quality and Safety in Health Care 12 (6) (2003) 453–457.

Parker, D.; Reason, J.; Manstead, A.; et al., Driving errors, driving violations and accident involvement, Ergonomics 38 (1995) 1036–1048.

Pearson, S.D.; Goulart-Fisher, D.; Lee, T.H., Critical pathways as a strategy for improving care: problems and potential, Annals of Internal Medicine 123 (1995) 941–948.

Phillips, J.M., The role of decision influence and team performance in member self-efficacy, withdrawal, satisfaction with the leader and willingness to return, Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes 84 (1) (2001) 122–147.

Read, S.J.; Levy, J., Effects of care pathways on stroke care practices at regional hospitals, International Medical Journal 36 (10) (2006) 638–642.

Reason, J.; Mycielska, K., Absent-Minded?. The Psychology of Mental Lapses and Everyday Errors. (1982) Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Reason, J.T., Human Error. (1990) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Reason, J.T.; Parker, D.; Lawton, R.; et al., Organisational controls and the varieties of rule-related behaviour, In: (Editor: Loomes, G.) Risk and Human Behaviour (1995) Economic and Social Research Council, York.

Reason, J., A systems approach to organisational error, Ergonomics 38 (1995) 1708–1721.

Reason, J.T.; Parker, D.; Lawton, R., Organisational controls and safety: the varieties of rule-related behaviour, Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology 71 (1998) 289–304.

Reason, J., Human error: models and management, British Medical Journal 320 (2000) 768–770.

In: (Editors: Roper, N.; Logan, W.; Tierney, A.) Using a Model for Nursing (1983) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Sackett, D.; Straus, S.; Richardson, W.; et al., Evidence Based Medicine: How to teach and practice EBM. (2000) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Schuster, M.A.; McGlynn, E.A.; Brook, R.H., How good is health care in the United States?Milbank Quarterly 76 (1998) 517–563.

Senders, J.W.; Moray, N.P., Human error: Cause, prediction and reduction. (1991) Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

Shimanoff, S., Communication rules. (1980) Sage, Beverly Hills.

Swash, M., In: (Editor: Hutchinson, R.) Hutchinson’s Clinical Methods21st Edition (2001) WB Saunders, London.

Tay, H.L.; Raja Latifah, R.J.; Razak, I.A., Clinical pathways in primary dental care in Malaysia: clinicians’ knowledge, perceptions and barriers faced, Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 18 (2) (2006) 33–41.

Vanhaecht, K.; De Witte, K.; Depreitere, R.; et al., Development and validation of a care process self-evaluation tool, Health Services Management Research 20 (3) (2007) 189–202.

Vanounou, T.; Pratt, W.; Fischer, J.E.; et al., Deviation-based cost modeling: a novel model to evaluate the clinical and economic impact of clinical pathways, Journal of American College of Surgeons 204 (4) (2007) 570–579.

Vitek, L.; Rosenzweig, M.Q.; Stollings, S., Distress in patients with cancer: definition, assessment, and suggested interventions, Clinical Journal Oncology Nursing 11 (3) (2007) 413–418.

Wagner, J.A.; Gooding, R.Z., Effects of societal trends on participatory research, Administrative Science Quarterly 33 (1987) 241–262.

Walby, S.; Greenwell, J.; Mackay, L.; et al., Medicine and nursing: professions in a changing health service. (1994) Sage, London.

Wolff, A.M.; Taylor, S.A.; McCabe, J.F., Using checklists and reminders in clinical pathways to improve hospital inpatient care, Medical Journal of Australia 181 (8) (2004) 428–431.

WHO World Health Report, (2000) World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Yee, S.K., What you need to know: guidelines to medical practitioners for proper maintenance of drugs and dispensing records (including controlled drugs), Singapore Medical Journal 39 (11) (1998) 520–522.

Yelland, J.; McLachlan, H.; Forster, D.; et al., How is maternal psychosocial health assessed and promoted in the early postnatal period? Findings from a review of hospital postnatal care in Victoria, Australia, Midwifery 23 (3) (2007) 287–297.