33 Procedures to Treat Benign Conditions

Many skin tumors and growths are benign and can be diagnosed based on their clinical appearance and history. These lesions can arise from the epidermis, the dermis, or the subcutaneous tissues. This chapter provides a detailed discussion of the most common benign skin lesions and their treatment options. Chapter 12 covered epidermal cysts, lipomas, digital mucous cysts, and hydrocystomas so these will not be covered here.

Acne Surgery

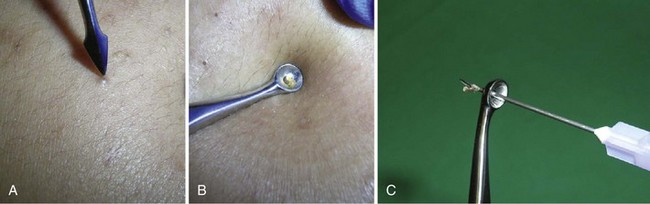

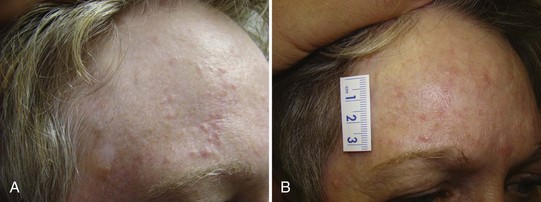

Acne surgery is the name given to the removal of open comedones (blackheads) with a comedone extractor in the clinician’s office. It can also be performed on actinic comedones or senile comedones. It is often performed for cosmetic reasons, but can also decrease pain around a comedone that is under pressure. Large inflammatory nodules and cysts are best treated with intralesional steroids rather than acne surgery (see Chapter 16, Intralesional Injections).

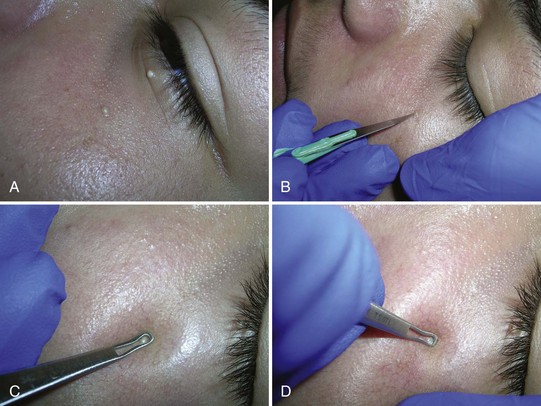

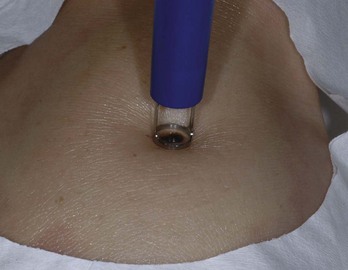

After informed consent, the comedones are cleaned with alcohol. No anesthesia is needed. The comedone is nicked with a No. 11 blade, a sterile needle, or the sharp end of a comedone extractor. Sebum, cells, and other debris are expressed out using pressure from a comedone extractor (Figure 33-1). If a comedone extractor is not available, one can be fashioned from a small paperclip bent to produce a homemade device. Clean the paperclip with an alcohol wipe before using it. Bill using acne surgery CPT code = 10040.

Acrochordons (Skin Tags)

Diagnosis

Treatment

Snip with Iris Scissors (Figure 33-3)

Angiomas/Angiokeratomas/ANGIOFIBROMAS

Diagnosis

Electrodesiccation for Small Lesions

Shave Excision with Electrodesiccation of the Base for Larger Lesions

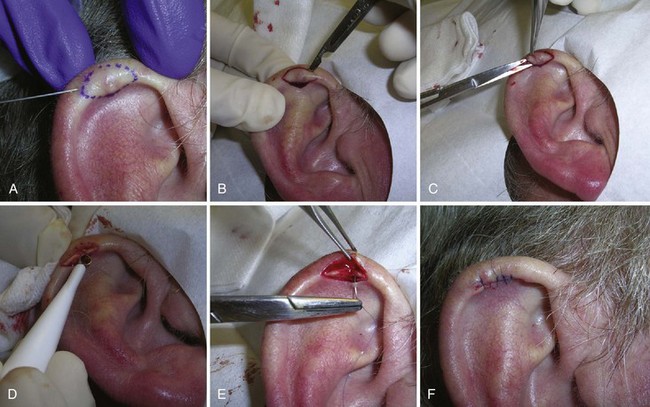

Chondrodermatitis Nodularis Helicis

Diagnosis

Treatment

Elliptical Excision

Electrodesiccation and Curettage

Cutaneous Horn

Treatment

Dermatofibromas

Diagnosis

FIGURE 33-10 Typical dermatofibroma with a hyperpigmented halo and a white and pink scar at the center.

(Copyright Daniel L. Stulberg, MD.)

Treatment

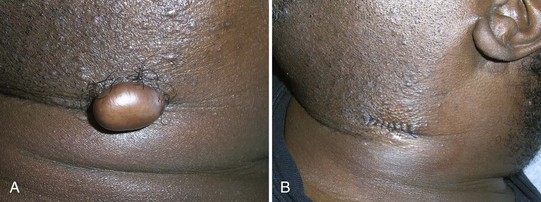

Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars

Treatment

FIGURE 33-14 Injecting an acne keloid with triamcinolone using a 27-gauge needle.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

FIGURE 33-15 Keloids formed on both sides of the earlobe secondary to ear piercing.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Lentigines (Solar)

Treatment

Milia

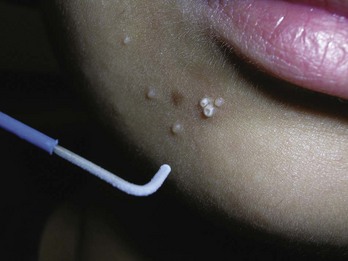

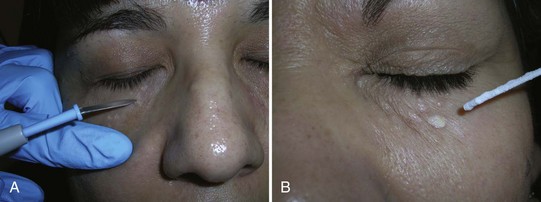

Molluscum Contagiosum

Treatment

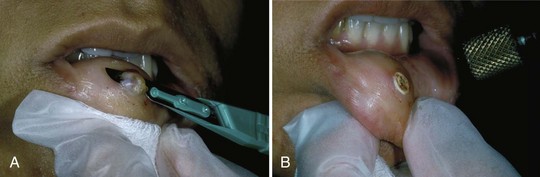

Mucocele

Treatment

Nevi

Diagnosis

Dysplastic Nevi (Atypical Moles)

There are many other types of nevi including epidermal nevi, speckled nevi, nevus sebaceous, Becker’s nevi, halo nevi, Spitz nevi, nevus depigmentosus, and nevus anemicus. The most important issue is to recognize melanoma and to biopsy any suspicious nevus in a timely fashion. See Chapter 34 for further information on biopsy techniques for lesions suspicious for melanoma.

Treatment

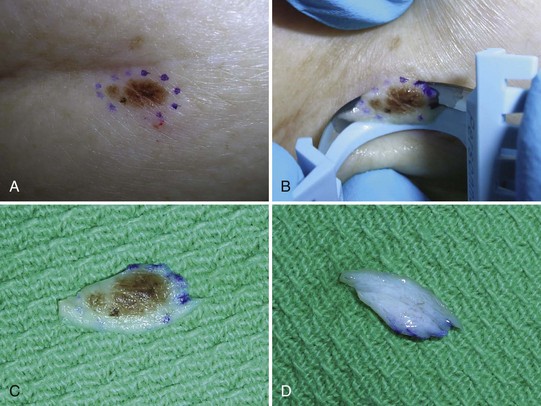

Dysplastic Nevus (Atypical Mole)

Studies show that 20% to 50% of melanomas appear to arise from a preexisting nevus. The annual risk of an individual nevus transforming into a melanoma is estimated to be only 1 in 200,000.8 The annual risk for an individual dysplastic nevus (DN) is extremely low as well but estimates are higher: 1 in 10,000 may transform into a melanoma in 1 year.9 This raises the question of whether incompletely removed DN should be re-excised with clear margins to prevent potential evolution into melanoma. Although most physicians would agree that DN demonstrating severe dysplasia should be re-excised given the risk of early or evolving melanoma, management of incompletely excised DN demonstrating mild or moderate dysplasia has remained an open question.10

In one study, 271 possible DN were biopsied using the shave technique in 163 (60%), punch technique in 74 (27%), and elliptical excision in 34 (13%).10 The authors found very low (3% to 4%) recurrence rates for both benign nevi and DN after biopsy, regardless of margin involvement, nevus subtype (junctional, compound, intradermal), or the presence of congenital features. The recurrence rates were lower than those seen in previous studies even though the follow-up period was greater than that in most of the other studies.10 A likely explanation is that they performed deeper and broader shave biopsies of clinically atypical nevi, whereas earlier studies primarily examined recurrence of benign nevi removed for cosmetic purposes, where a more superficial shave biopsy may have been done to minimize scarring. Failure of nevi with positive margins to recur suggests that in most cases, residual nevus cells in the biopsy wound are not of sufficient number (or do not have the capacity) for regeneration and pigment production.10

The only statistically significant association found with nevus recurrence was the biopsy method, with the shave technique being significantly associated with recurrence.10 One explanation for a higher recurrence rate with shave biopsies compared with punch biopsies is that nevus recurrence may be more likely to originate from a deep rather than lateral margin—which was observed in most recurrent nevi in this study.10 Another explanation for the association between shave technique and recurrence is that lesions that are shaved tend to be much larger than those selected for punch biopsy. Larger lesions may contain more proliferative cells or be more likely to recur from residual cells for other reasons that are presently unclear.10

Goodson et al.’s results10 are consistent with those of Kmetz et al.,11 who found that no melanomas developed during a 5-year period after biopsy of 55 atypical nevi (26 lesions with at least one positive margin and 29 with clear margins) that were not re-excised.11 Both studies suggest that lesions that demonstrate only mild or moderate dysplasia may not need to be re-excised given their low likelihood of recurrence, and can be followed clinically for evidence of recurrence or development of any concerning features.10,11

Congenital Nevi

Congenital nevi are frequently large and can meet all five ABCDE criteria (see page 434) as a potential melanoma. The clinical diagnosis of congenital nevus is made based on history because they have been present since birth or occurred within the first month or two of birth. Biopsy is indicated if a congenital nevus changes in color, there is a new growth within the nevus, or bleeding without trauma occurs within the nevus. It was long taught that all congenital nevi should be removed because of the potential for malignancy. Large lesions have the greatest potential to become malignant, but they may be so large as to cause major scarring if removed (>20 cm). So, they will need to be watched closely or excised by a plastic surgeon in multiple procedures. With very dark, almost black lesions, early changes will be difficult to detect. The most recent approach recommends following these lesions as with any other nevus and removing them for any observed changes or concerns.

In a prospective study of 230 medium-sized congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) (1.5 to 19.9 cm) in 227 patients from 1955 to 1996 with average follow-up period being 6.7 years to an average age of 25.5 years, no melanomas occurred in these nevi. The authors concluded that the results of this follow-up study do not support the view that there is a clinically significantly increased risk for malignant melanoma arising in banal-appearing medium-sized CMN or that prophylactic excision of all such lesions is mandatory. Lifelong observation seems a reasonable alternative for medium-sized CMN without unusual features.12 With the affordability of digital cameras, careful lifelong follow-up with photographs should be easy to accomplish.

Bathing Trunk Nevi

Bathing trunk nevi are very large CMN at higher risk of becoming melanoma. According to Habif,13 50% of the melanomas in bathing trunk nevi develop before age 5. There is a risk of neurocutaneous melanoma, which requires an MRI for diagnosis. Melanomas in these large congenital nevi can be missed by observation because they may have nonepidermal origins. In a systematic review, the risk of developing melanoma and the rate of fatal courses were by far highest in CMN ≥40 cm in diameter.14 Although there are no evidence-based data to support this, surgical excision of bathing trunk nevi is recommended by some experts.13 This requires multiple stages and the use of tissue expanders. This is done by plastic surgeons and the financial cost is great. The pain and suffering to the child is substantial and needs to be weighed in the decision of whether or not to recommend surgery.

Spitz Nevus

In 1947, Sophie Spitz described “juvenile melanoma” in which prognosis was frequently excellent. However, Spitz reported one patient with “juvenile melanoma” that had a fatal metastases. Currently there is still a lack of consensus about Spitz nevi but pathologists no longer use the term juvenile melanoma. Some experts recommend that all Spitz tumors be completely excised with clear margins.15 Atypical Spitz nevi should be excised with wider margins up to 1 cm.15 All patients with a history of a Spitz nevus should be carefully monitored by regular examinations for recurrence and metastasis. See Chapter 32 for dermoscopic features of the Spitz nevus.

Neurofibromas

Diagnosis

Treatment

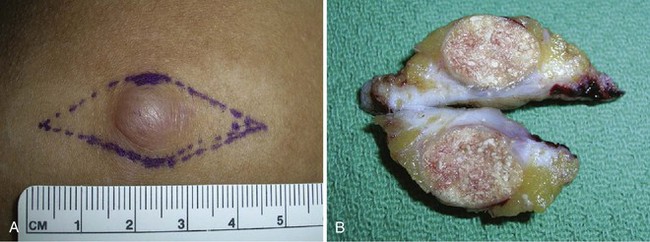

Pilomatricoma

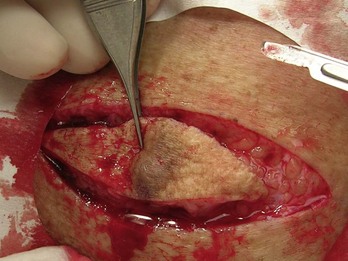

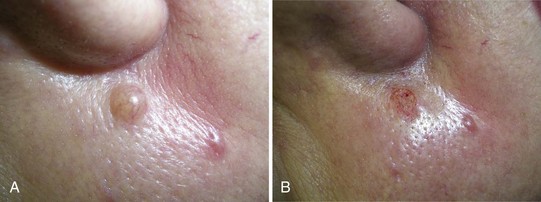

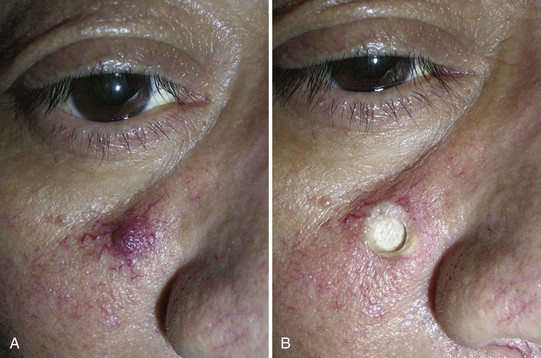

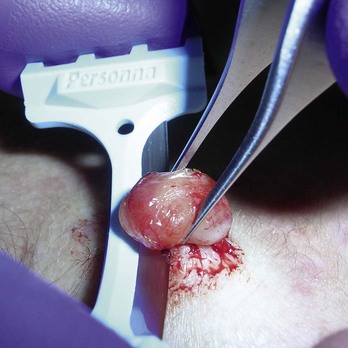

Pyogenic Granuloma (Lobular Capillary Hemangioma)

Diagnosis

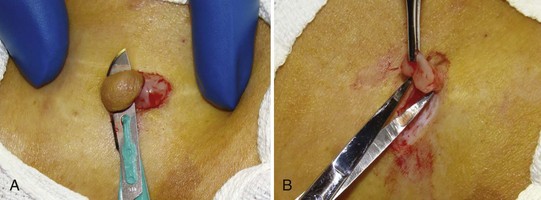

FIGURE 33-32 Shave excision of a pyogenic granuloma using a DermaBlade. The base was then curetted and electrodesiccated.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

In a randomized controlled trial that compared cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen versus curettage and electrodesiccation of patients with pyogenic granuloma, the curettage and electrodesiccation had the advantage of requiring fewer treatment sessions to achieve resolution and better cosmetic results.16 Treatment of the pyogenic granulomas resulted in complete resolution of all lesions after one to three sessions (mean 1.42) in the cryosurgery group and after one to two sessions (mean 1.03) in the curettage group (P < 0.001). Twenty-three patients (57.5%) in the cryotherapy group and 25 patients (69%) in the curettage group had no scar or pigmentation abnormality. From this study and personal experience, we conclude that curettage and electrodesiccation is the preferred treatment option over cryosurgery.

Treatment

Shave, Curettage, and Electrodesiccation

Sebaceous Hyperplasia

Diagnosis

Treatment

Seborrheic Keratoses and Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

Diagnosis

Treatment

Alternative treatment methods that require local anesthesia include the following:

Syringomas

Treatment

Telangiectasias and Spider Angiomas

Treatment

Telangiectasias may be treated for cosmetic reasons using electrosurgery or laser treatments.

Trichoepithelioma

Diagnosis

Treatment

Warts, Common

Treatment

Cryosurgery

Warts, Plantar

Diagnosis

Warts, Venereal (Condyloma Acuminata)

Treatment

Podofilox 0.5% Solution or Gel (Condylox)

1. Goldberg DJ, Marcus J. The use of the frequency-doubled Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of small cutaneous vascular lesions. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:841-844.

2. Rusciani L, Rossi G, Bono R. Use of cryotherapy in the treatment of keloids. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19:529-534.

3. Katz TM, Glaich AS, Goldberg LH, Friedman PM. 595-nm long pulsed dye laser and 1450-nm diode laser in combination with intralesional triamcinolone/5-fluorouracil for hypertrophic scarring following a phenol peel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1045-1049.

4. Ross EV, Smirnov M, Pankratov M. Intense pulsed light and laser treatment of facial telangiectasias and dyspigmentation: some theoretical and practical comparisons. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1188-1198.

5. Small R. Aesthetic procedures in office practice. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:1231-1237.

6. Marcushamer M, King DL, Ruano NS. Cryosurgery in the management of mucoceles in children. Pediatr Dent. 1997;19:292-293.

7. Tran TA, Parlette HLIII. Surgical pearl: removal of a large labial mucocele. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:760-762.

8. Tsao H, Bevona C, Goggins W, Quinn T. The transformation rate of moles (melanocytic nevi) into cutaneous melanoma: a population-based estimate. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:282-288.

9. Naeyaert JM, Brochez L. Clinical practice. Dysplastic nevi. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2233-2240.

10. Goodson AG, Florell SR, Boucher KM, Grossman D. Low rates of clinical recurrence after biopsy of benign to moderately dysplastic melanocytic nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:591-596.

11. Kmetz EC, Sanders H, Fisher G, et al. The role of observation in the management of atypical nevi. South Med J. 2009;102:45-48.

12. Sahin S, Levin L, Kopf AW, et al. Risk of melanoma in medium-sized congenital melanocytic nevi: a follow-up study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:428-433.

13. Habif T. Clinical Dermatology, 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004.

14. Krengel S, Hauschild A, Schafer T. Melanoma risk in congenital melanocytic naevi: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1-8.

15. Situm M, Bolanca Z, Buljan M, et al. Nevus Spitz—everlasting diagnostic difficulties—the review. Coll Antropol. 2008;32(Suppl 2):171-176.

16. Ghodsi SZ, Raziei M, Taheri A, et al. Comparison of cryotherapy and curettage for the treatment of pyogenic granuloma: a randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:671-675.

17. Daniels J, Craig F, Wajed R, Meates M. Umbilical granulomas: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F257.

18. Krupashankar DS. Standard guidelines of care: CO2 laser for removal of benign skin lesions and resurfacing. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74(Suppl):S61-S67.

19. Riedel F, Bergler W, Baker-Schreyer A, et al. Controlled cosmetic dermal ablation in the facial region with the erbium:YAG laser. HNO. 1999;47:101-106.

20. Khatri KA. Treatment of cutaneous lesions using a novel 2.94 erbium laser with micron tips. Presented at American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, 2009, National Harbor, MD.

21. Richey D, Hopson B. Treatment of sebaceous hyperplasia with photodynamic therapy. Cosm Dermatol. 2004;17:525-529.

22. No D, McClaren M, Chotzen V, Kilmer SL. Sebaceous hyperplasia treated with a 1450-nm diode laser. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:382-384.

23. Karam P, Benedetto AV. Syringomas: new approach to an old technique. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:219-220.

24. Goldman MP, Bennett RG. Treatment of telangiectasia: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:167-182.

25. Mamelak AJ, Goldberg LH, Katz TM, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:102-106.

26. Urquhart JL, Weston WL. Treatment of multiple trichoepitheliomas with topical imiquimod and tretinoin. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:67-70.

27. Gibbs S, Harvey I, Sterling JC, Stark R. Local treatments for cutaneous warts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;CD001781.

28. Phillips RC, Ruhl TS, Pfenninger JL, Garber MR. Treatment of warts with Candida antigen injection. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1274-1275.

29. Karsai S, Czarnecka A, Raulin C. Treatment of xanthelasma palpebrarum using a pulsed dye laser: a prospective clinical trial in 38 cases. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:610-617.