Chapter 8 Problems in older people

Introduction

Medical emergencies are common in older people and they may have difficulty accessing suitable health care once their GP practice is closed. They are less likely to use schemes such as NHS Direct than other parts of the population.1 They or their carers are more likely to dial 999 if they have an urgent medical problem. The care of the elderly is an increasing proportion of work for GP out-of-hours services, ambulance services and Emergency Departments.

Community systems for the care of older people

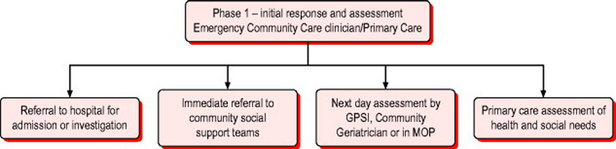

Figure 8.1 sets out the range of outcomes from community emergency assessment and shows the ideal system to respond to these emergencies. The community emergency medicine clinician carries out initial crisis support and a brief needs assessment. In significant numbers of older patients this will need to be backed up by either hospital or community services. The keys to success in such a system are excellent communication, mutual respect and clear referral pathways with common documentation systems.

Primary survey positive patients

The criteria for recognition of immediately life threatening problems are the same as for younger patients (Box 8.1). However the interpretation of vital signs may be more difficult and abnormalities need to be taken in context of pre-existing morbidity. A history from a reliable witness is essential. Previous neurological problems can make the GCS permanently <12. Similarly, the elderly are more prone to excessive bradycardia from cardiac medication but on the other hand, symptomatic heart block is common. Oxygen saturations should be interpreted in light of the known medical history and clinical setting.

Primary survey positive patients should be transferred as soon as possible by paramedic ambulance to an A&E Department or an Emergency Admissions Unit depending on local protocols. The exception might be those patients with documented ‘end of life decisions’ such as Advanced Directives and clear, agreed treatment plans which might include ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ (DNAR) orders.

Primary survey negative patients

In the elderly patient a greater emphasis must be given to factors other than the ‘medical problem’ alone. The variables to be considered are given in Box 8.2.

Cognitive status of the patient

The presence of cognitive impairment often renders the history and self-reported ability with activities of daily living unreliable. It is important for any community practitioner to be able to recognise cognitive impairment and, where possible, confirm history with a reliable witness. Impaired cognition in someone living alone might mean they are unable to look after themselves despite an illness being only minor.

Non-specific presentations of illness in older patients

These ‘non-specific’ presentations are common and create significant diagnostic and management problems. A seemingly minor injury or illness can be due to several underlying medical conditions. The commonest causes of ‘non-specific’ presentations are listed in Box 8.3. Full details are listed in many textbooks.2 The presenting complaint may be determined more by pre-existing mental or physical frailty than the acute illness.

Subjective information – history

Not all patients in this age group are able to give a reliable history and thus it is essential to glean as much information as possible from carers. Details of general history taking are reviewed in Chapter 2. Specific elements of the history, including the social history and features highlighted in Box 8.2, will determine the need for further investigation or transfer.

Objective information – examination

Vital signs (Box 8.4) are, as always, important but may be altered by pre-existing morbidity. The GCS is the most obvious example where pre-existing confusion will make assessment of the verbal score difficult. Similarly, pulse and blood pressure may be altered by pre-existing medications such as β-blockers. Any concern about the vital signs or general appearance of the patient should trigger an immediate hospital assessment.

The next stage is a focused systems examination. A full examination is required but given the huge number of problems causing falls or confusion certain areas should be given additional emphasis. The examination described in Box 8.5 is aimed at patients with falls but most also applies to patients with confusion, including assessments of both physical and mental status.

Box 8.5 Examination and simple tests for older patients with immobility, falls or acute confusion

There are many tools available for the assessment of cognitive function. Each has limitations but they can give an indication of problems with cognition and can be used to follow progress. Box 8.6 shows the 10-question Hodkinson Abbreviated Mental Test score which combines brevity with validity. Questions have to be asked in the order shown and are given 1 mark for the correct answer or no mark. A score below 8 out of 10 implies cognitive impairment.

Management plan

Older adults prefer to be treated at home and where possible this should be facilitated. Removal to unfamiliar environments can precipitate distress and confusion and lead to a further deterioration in the patient’s clinical condition and a further loss of independence. Transfer to hospital must therefore be reserved for those cases where further investigations are likely to be of benefit or where an adequate standard of care cannot be provided in the home. Competent elderly patients must be fully involved in making decisions about their care plan and any interventions must always be subject to their fully informed consent. Different management strategies are now discussed.

Treat and leave/review

Details of treatment of specific minor injuries are described in Chapter 13. Patients with minor illness can be treated at home if adequate support is available. However, it should be ensured that the patient and their carers clearly understand when and how to seek further advice or help if their condition does not improve or deteriorates. If patients do not require further referral their GP must still be informed of the ‘emergency’ episode and they can then decide when to review the patient.

Treat and refer

Another reason for referral to hospital would be for X-rays to exclude fracture. Referral pathways should be established to enable the community emergency practitioner to directly refer patients for an appropriate X-ray with varying urgency. X-ray of what might be a minor fracture may be deferred if pain can be controlled with simple analgesics to avoid an admission in the middle of the night. However, if the patient is unable to care for themselves or the suspected fracture is associated with significant pain or neurovascular problems, an X-ray may be required in a shorter time-scale. Self-mobilising patients with suspected bony injuries to the upper limbs will rarely require transfer by emergency ambulance and alternative forms of transport should be considered.

Treat and transfer

There are several groups of patients in this category. Some have worrying symptoms, as in Box 8.7. Others are less ill but lack suitable support at home or appropriate services to support the patient at home cannot be organised. If a bed in an Intermediate Care facility cannot be arranged, these patients will need to be taken to hospital. Finally, there are those who cannot be properly assessed at home and who need to be brought to the Emergency Department for this to be done.

Other factors to consider

Any clinician seeing an older person in their home has the opportunity to assess the level of care that person is receiving and whether they are being subject to abuse. The pattern of injury seen in physical abuse is often similar to those sustained during a fall but if the patient denies a fall the possibility of elder abuse should be considered. It should also be remembered that psychological, financial and sexual abuse plus abuse through neglect can all lead to physical and mental decline resulting in an emergency assessment. If elder abuse is suspected, social services should be informed. Please visit www.elderabuse.org.uk for more information and advice.

1 NHS Direct in England. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General. London: National Audit Office, 2002.

2 Kenny RA. Falls and syncope. In: Evans GJ, Williams FT, Beattie LB, Michel J-P, Wilcock GK, editors. Oxford textbook of geriatric medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

3 Mathias S, Nayak US, Isaacs B. Balance in elderly patients: The ‘get-up and go’ test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67:387-389.

4 Hodkinson HM. Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment. of mental impairment in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1972;1:233-238.