Visual Problems

As the sense of sight is critical, patients who present with visual disturbance are often very distressed. Below is a list of common conditions that may give rise to visual problems, grouped according to symptoms.

History

First establish if visual loss is monocular or binocular. Ocular or optic nerve pathology generally causes monocular visual loss, whereas lesions at the optic chiasma or more posteriorly cause binocular loss that will respect the vertical meridian. Loss of central vision may be due to macular or optic nerve pathology. Retinal lesions cause a ‘positive’ scotoma (the patient is aware that part of the field is obstructed), whereas damage posterior to the retina causes a ‘negative’ scotoma (the patient does not see that a segment of the visual field is missing).

Visual disturbances

Bilateral flashing lights and zigzag lines are often reported by patients suffering with attacks of migraine. This is accompanied by throbbing headache, nausea, vomiting and photophobia. Posterior vitreous detachment, vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment are all associated with floaters and flashing lights. Visual acuity and visual fields are normal at first but may be impaired with a large vitreous haemorrhage or advanced retinal detachment.

Blurring of vision

Errors of refraction (long- or short-sighted) are the most common cause of blurring of vision. This is a common problem and is usually corrected with glasses by optometrists. Head and eye injuries may also give rise to transient blurring of the vision. With acute angle-closure glaucoma, corneal oedema will give rise to the appearances of haloes around lights and is associated with a red and painful eye.

Loss of vision

Visual loss may be partial or total. The description of the area of partial visual field loss is very informative. Complaints of vertical visual field losses are due to lesions posterior to the optic chiasma and most commonly caused by strokes, although similar effects can be produced by space-occupying lesions such as cerebral tumours. Horizontal visual field losses imply that the cause lies within the retina and is usually due to retinal vascular occlusions. Patients with glaucoma may complain of tunnel vision, and patients with macular degeneration may experience sudden central visual field loss.

Sudden total visual loss is usually due to a vascular aetiology. Amaurosis fugax is sudden transient monocular blindness due to atheroembolism of the ophthalmic artery. Patients classically complain of a ‘curtain descending across the field of vision’. With giant cell arteritis affecting the ophthalmic artery, sudden onset of blindness can occur in conjunction with the symptoms of temporal headache, jaw claudication and scalp tenderness. It is often associated with polymyalgia rheumatica. Papilloedema may cause transient visual loss, lasting seconds, related to posture.

Monocular blindness due to optic neuritis may occur with multiple sclerosis; it is often associated with retro-orbital pain that worsens with eye movements and starts with a progressive dimming of vision over a few days.

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common cause of blindness in Western society. In addition, diabetics are also more prone to develop cataracts and glaucoma. In the elderly, gradual onset of visual loss may be due to cataracts, glaucoma or age-related macular degeneration. Owing to the gradual onset of symptoms, these groups of patients may present very late. A cataract may be visible on examination of the eye.

Examination

Visual acuity unaided and corrected with a pinhole should be assessed with a Snellen chart. If visualisation of the largest letter is not possible, then assess vision by counting fingers. Further tests to use are those of movement and, finally, the ability to discriminate between light and dark. With refractive errors, vision can be corrected by viewing the Snellen chart through a pinhole. Visual fields are examined by confrontational testing, and the extent of visual field loss can be assessed approximately.

Pupillary response to light (direct and consensual) allows the assessment of the visual pathway. Direct light reflex may be lost in lesions involving the unilateral optic nerve and with central retinal artery occlusion.

Colour vision will be reduced disproportionately compared with visual acuity in optic nerve diseases. This may be assessed with the use of Ishihara plates.

Fundoscopy

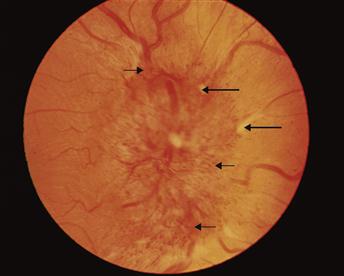

A wealth of information is obtained on fundoscopy. The red reflex is lost with cataracts. Examination of the retina may reveal background retinopathy with diabetes, consisting of dot and blot haemorrhages with cotton-wool spots. With hypertensive retinopathy, silver wiring, arteriovenous nipping, retinal haemorrhages and eventually papilloedema may be appreciated. Growth of new vessels on the retina indicates proliferative retinopathy. An infarcted retina appears oedematous and pale; the macula appears prominent and red (cherry-red spot). Detached retinal folds may be seen, and clots of blood are visible with vitreous haemorrhage. The margins of the optic disc become blurred with papilloedema and optic neuritis but later may appear pale. A cupped optic disc appearance occurs with chronic glaucoma.

Upon completion of the examination of the eye, a neurological examination should be performed, followed by a cardiovascular examination to exclude sources of emboli. The rhythm of the pulse is assessed for atrial fibrillation and the heart and carotids are auscultated for murmurs. The blood pressure is measured to exclude hypertension.

General Investigations

■ ESR and CRP

Giant cell arteritis.

■ Blood glucose

Glucose ↑ diabetes.

■ Intraocular pressure measurements

↑ with glaucoma.

■ Perimetry

Formal charting of visual fields. Arcuate scotomas are found with glaucoma. Central scotomas may be seen with optic neuritis. Bitemporal hemianopias/homonymous hemianopias and quadrantanopias in neurological pathology.