Principles of transplantation surgery

Introduction

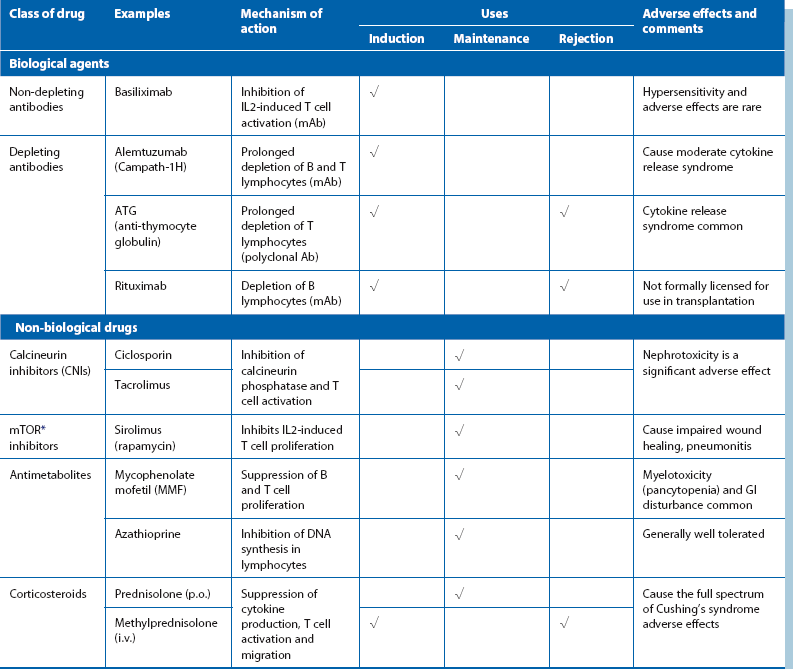

Chemical immunosuppression designed to attenuate graft rejection has continued to advance, leading to improving success rates with transplantation of an expanding range of organs and tissues (see Table 14.1). Human cornea, kidney, liver, pancreas, heart, heart and lung, single or double lung and bone marrow transplantation are all now standard, although not free of rejection or other complications (see: http://www.ctstransplant.org/). Even face transplants are now achieving success.

Transplant immunology

Immunosuppression

Immunosuppressant drugs are broadly classified into biological (monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies) and non-biological agents; the characteristics of the main examples are summarized in Table 14.1. Immunosuppressive drugs are almost always employed in combination to allow lower doses of individual agents to minimise side-effects. These include infections, impaired wound healing, predisposition to certain malignancies (e.g., skin and Epstein–Barr virus-related lymphoproliferative disorders) and bone marrow suppression. A widely used combination is induction with basiliximab, followed by maintenance on prednisolone, tacrolimus and MMF.

Graft rejection: Graft rejection continues to be a problem despite the increasing range of immunosuppressive agents. It can present in several ways:

Hyperacute rejection: Hyperacute rejection is due to the presence of pre-formed antibodies (e.g. against ABO antigen) in the recipient. It occurs within minutes of reperfusion and is now exceedingly rare owing to improvements in cross-matching techniques.

Acute rejection: Acute rejection occurs in up to 30% of transplants, most commonly during the first 3 months post-transplant. It is predominantly T cell-mediated but can be antibody-mediated in about 10%. It can usually be reversed by a temporary increase in immunosuppression, most often in the form of a short course of high-dose corticosteroids.

Practical problems of transplantation

‘Brain death’

The legal criteria for brain death in the UK are summarised in Box 14.1; similar criteria are used in other countries. In the UK, the diagnosis of brain death is made on purely clinical criteria; electrocardiography, cerebral blood flow and other neurophysiological tests are not required. Appropriate clinical examination must be performed by two senior doctors independent of the transplant team and must be repeated at least twice.

Organ preservation and transport

• An osmotic agent to provide extracellular oncotic force to prevent cellular oedema

After retrieval, the bag containing the organ and preservation fluid is usually packed in ice (static cold storage) while awaiting transplantation. Alternatively, kidneys may be connected to a machine to continuously circulate cold preservation solution (machine perfusion). Machine perfusion is more expensive and cumbersome than static cold storage; its potential advantages include a more physiological environment and the ability to identify and discard non-functioning kidneys with poor perfusion characteristics.

Specific organ transplants

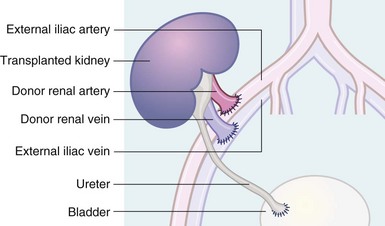

The kidney is transplanted into an extraperitoneal location in the iliac fossa and the renal vessels anastomosed to the iliac artery and vein (see Fig. 14.1). The ureter is implanted into the bladder using an intramural tunnel to prevent reflux. Non-functioning kidneys are usually left in situ unless infected or causing unmanageable hypertension.