2 Principles of surgical oncology

Diagnosis and staging

Staging

Various surgical procedures such as endoscopy and staging laparotomy aid in defining the extent of disease as well as obtaining histological confirmation of metastatic disease. These are covered in detail for specific malignancies. One example is the use of laparoscopy as an adjunct to detect small peritoneal and liver metastases reduces the number of ‘open and close’ laparotomies by less than 5% in stomach cancer.

Curative surgery

Surgery of the primary tumour

Depending on the type of cancer and anatomical site, curative surgery can be:

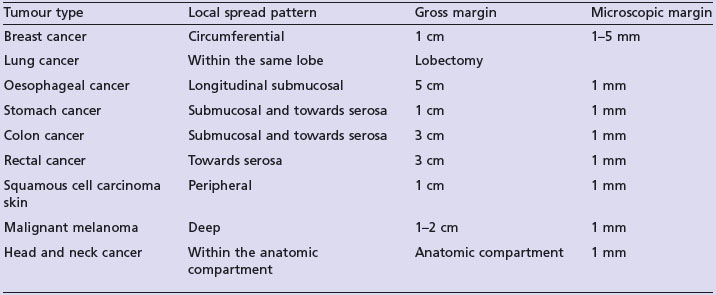

At the time of surgery exposure and shedding viable tumour cells should be avoided if possible. Certain tumours have a propensity to recur along surgical incision lines or drainage sites e.g. mesothelioma and sarcoma. A curative resection is aimed at a gross visible margin as imaging modalities will not identify microscopic disease. This gross margin depends on the type of malignancy and pattern of local spread. An adequate gross margin helps to ensure adequate microscopic margin of resection. Table 2.1 shows examples of the gross resection margin and microscopic resection margin for some common tumours.

Surgery of regional lymph nodes

However, in many situations the role of lymph node dissection in overall survival remains controversial. In practice, patients with involved lymph nodes undergo node dissection whereas the role of elective lymph node dissection is dependent on the site of cancer, type of cancer and other prognostic factors. Benefits of nodal dissections in different cancers are discussed in the corresponding chapters.

Metastatectomy as part of curative surgery

Resection of isolated metastatic lesions is useful for a selected group of patients in certain cancers (Box 2.1). In general this is undertaken for patients with surgically resectable metastatic disease at presentation or in a very select group of patients with good performance status with a long disease-free survival after treatment of the primary tumour. In the absence of proper randomized studies it is not known whether the observed therapeutic benefit is actual or due to the strict selection process (selection bias). The common situations are resection of isolated or limited liver metastases in colorectal cancer which results in 20–40% 5-year survival (p. 164). Pulmonary metastatectomy in sarcomas leads to a 5-year survival of 20–25% (p. 259). An alternative is the evolving use of radiofrequency ablation.

Risk reduction surgery

Less than 5% patients have a genetic component to their cancer (p. 45). Increasing understanding of the development of genetically associated cancers has led to prophylactic surgery for some patients. Box 2.2 shows the indications for common prophylactic surgeries. Appropriate genetic testing and counselling is, however, an absolute pre-requisite prior to any prophylactic surgery. Women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations have a high risk of breast cancer which is reduced by 90–95% with bilateral mastectomy. However, the decision to undergo prophylactic mastectomy should be done after careful discussion on explaining the future quality of life, potential surgical risks and wishes of the patient. Alternative risk reduction methods such as use of tamoxifen and prophylactic oophorectomy after completion of family should also be considered. Another example is FAP and prophylactic colectomy (p. 50).

Box 2.2

Potential indications for risk reducing surgery

| Surgery | Indication |

|---|---|

| Bilateral mastectomy |

Minimal access and robotic surgery

The role of minimal access surgery is being increasingly studied in the management of solid tumours. It is being more often used in abdominal malignancies and studies show that laparoscopic surgery results in the same long term survival as that of open surgery, with no increased risk of abdominal wall recurrence, less surgical morbidity and quick return to normal function. Laparoscopic surgery is an accepted modality of surgical treatment in gastric, kidney, adrenal and colorectal cancers. Video-assisted thoracic surgery for stage I lung cancer is a particularly attractive option for elderly patients.