5 Principles of palliative care nursing

The meaning of palliative care

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines palliative care as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual. Palliative care:

– provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

– affirms life and regards dying as a normal process

– intends neither to hasten nor postpone death

– integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care

– offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death

– offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their own bereavement

– uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement counselling if indicated

– will enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness (WHO 2003).

Provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

Often the focus of care can be on relieving a physical pain without considering wider issues for the patient. Dame Cicely Saunders, the doctor who opened St Christopher’s Hospice in London in 1967, introduced the concept of ‘total pain’ (Saunders 1964) which encompassed physical, emotional, social, spiritual and psychological aspects of life. The idea of total pain became central to the multidisplinary team (MDT) approach of the modern hospice movement during the 1970s and 1980s. This idea of total pain has grown to include the consideration of the ‘inner self’ which is known only to the patient. This inner self is the person’s own thoughts about what is happening in their lives and can have a positive or negative effect on their perception and experiences of pain.

We return to the concept of physical, emotional, social and psychological aspects of caring for a patient in Chapter 15 on managing symptoms.

Affirms life and regards dying as a normal process

How can dying be ‘normal’ when a person is young, in a lot of pain or just retired and looking forward to the years ahead? This is one of the main challenges facing those who care for a patient in the palliative care phase. What we must consider is that from the time a patient is recognised as being in the palliative stages of their illness, it is important to support them to get a degree of normality. Thinking of ways to keep things normal is a really helpful way to support a patient and their family and can be a good way of building relationships and helping manage symptoms.

Intends neither to hasten nor postpone death

As a member of the NMC register, it is essential to adhere to the law of the country you are working in (NMC 2008). In providing palliative care, it is important to balance managing distressing symptoms and ensuring our actions do not hasten the end of life. The terms ‘euthanasia’ and ‘assisted dying’ are often used in association with managing distressing symptoms and there is a lot of confusion about what actions we undertake and how these actions are not ‘ending life’ instead of managing symptoms and comfort.

Integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care

The word ‘spiritual’ comes from the Latin word ‘spiritus’ meaning breath, air, breathing. This idea of giving life underpins the definitions we have of spirituality and goes far beyond the following of a religion. Section 2 explores in detail different aspects of religious and cultural beliefs in order to help you understand how to meet patients’ (and families’) spiritual needs before, during and after death.

Understanding spirituality can help to care for a patient who might be experiencing distress. Psychological and spiritual care can be extended to a patient’s family, both before and after death. A new concept in recognising and addressing spiritual needs is the work on ‘Being’ (Sheard 2007):

In addition to the Being approach, consider the following definitions of spirituality:

‘… the inner thing that is central to the person’s being and what makes a person a unique individual …’ (Narayanasamy 2006:6)

‘… is my being, my inner person. It is who I am, unique and alive. It is expressed through my body, my thinking, my feelings, my judgements and my creativity. My spirituality motivates me to choose meaningful relationships …’ (Stoll 1989:6)

What does ‘spiritual’ mean to you? Complete the following statement:

Now make a list of how you can ‘be’. Consider how this might differ from ‘doing’.

We are now beginning to see the links between physical wellbeing and psychological and spiritual distress. We refer to this as ‘holistic care’ and it is a fundamental part of the definition and practice of palliative care. Being able to understand the holistic needs of a person helps to plan care and reduce distress and is a fundamental aspect of providing dignified and compassionate care (McSherry & Ross 2010). We explore psychological distress in more detail in Chapter 15 on managing symptoms.

Offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their own bereavement

When on your practice placement, find out the following:

Do family and friends know the nearest bus stop to use? Details of bus services? Where to get a taxi?

Will the visiting hours exclude a specific family member if they are working a shift pattern or a child at school?

Are flowers allowed in the clinical area? If not, do the family and friends know the alternatives they could bring in?

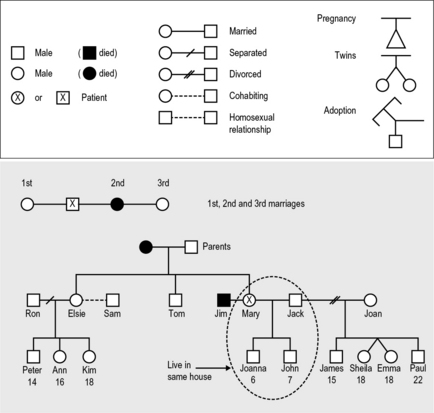

Who are the family members? Are they local or living abroad? One way of doing this is by completing a family tree or ‘genogram’ (Fig. 5.1). Have a go at writing your own family tree using the template given in Figure 5.1. It is important to keep each generation on its own line.

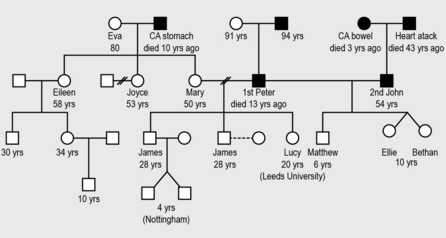

Mary is a 50-year-old patient.

Her mother is called Eva and is 80 years old.

Her father died 10 years ago from stomach cancer.

Her sister Eileen is 58 and has one daughter who is married with a 10-year-old son. She also has a son who is 30 years old.

Mary’s other sister is called Joyce and she is 53 years old. She is divorced with no children.

Mary married Peter, however they divorced 15 years ago. Peter died 13 years ago and both his parents are still alive.

Mary and Peter had three children:

After her divorce to Peter, Mary married John who is 54 years old and they have twin daughters – Ellie and Bethan – who are 10, and a son – Matthew – who is 6 years old.

John’s mother died 3 years ago from cancer of the bowel. John’s father died of a heart attack when he was 11 years old.

This is really important when things suddenly change and you need to offer extra support to family members. Knowing who people are and who is missing is a vital part of managing a distressing situation.

Uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement counselling if indicated

Palliative care is not just about looking after a dying person but also the family at the time of death and into bereavement. Often in busy ward areas, the last time a nurse will have contact with a bereaved family will be when they leave the ward immediately after the death. This can leave professionals with a mixture of emotions. For some, not being on duty at the time of death can be upsetting. We continue to consider bereavement support in Chapter 16.

The core terms used within palliative care

Some things you can do to help work though your feelings in this type of situation:

Having spent some time exploring in detail what the definition of palliative care means in practice, we now look at some common terms that are linked to palliative care, to avoid misunderstanding both by the healthcare team and for patients and their families. Some common terms you may hear used in your practice placement include the following.

Terminal care

This refers to a period when, despite the best efforts of patients, carers, friends, relatives and the multidisciplinary team, symptoms become more difficult to manage. The onset and duration of this period are as unique as every human being (Buckley 2008). There can sometimes be confusion about how the word ‘terminal’ is used and understood. A person can be referred to as having ‘terminal cancer’, making reference to the fact that the cancer cannot be cured, however they may have months or years to live a good quality of life. At other times, the ‘terminal stage’ is when a patient is in the last days or hours of life.

End of life pathway

The End of Life Care Strategy(DH 2008) introduced the concept of a ‘pathway’ which would focus on the last year of life. This pathway is applicable to any patient diagnosis and helps health and social care professionals to plan ahead and ensure all the services possible are used to care of the patient and family. We return to this pathway when we look in detail at end of life best practice tools in Chapter 16.

Voluntary agency

Macmillan Cancer Relief: http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Home.aspx (accessed November 2011).

Marie Curie Cancer Care: http://www.mariecurie.org.uk/ (accessed November 2011).

Sue Ryder Care: http://www.suerydercare.org/ (accessed November 2011).

This is an organisation funded mainly through voluntary money rather than through a government department. Some voluntary organisations are funded 50% by government money. It can be a registered charity and it may have staff in paid employment, as well as relying heavily on fundraising activities and volunteers. Some examples of voluntary organisations providing palliative care in England are Macmillan Cancer Relief, Sue Ryder Care and Marie Curie Cancer Care.

Palliative care today

Consideration of the dying and the care we provide has gained a much higher profile in recent years. It became recognised as a medical specialty in 1987 leading to a new training programme for doctors to work towards becoming consultants in palliative medicine (Doyle et al 2005). Palliative care consultants have an essential role in the multiprofessional team and can be found in hospices and teams covering both acute hospital wards and community settings.

• Discovery of penicillin has reduced infections.

• Improvements in living conditions; housing, sanitation and water supply.

• Improvements in midwifery care leading to a fall in infant mortality.

• Improvements in factories and workplace safety reducing industrial accidents.

• More people living in large cities leading to changes in lifestyle: more sedentary workers having less exercise alongside changes in diet leads to more long-term conditions, for example cancer, heart disease and stroke.

• Growth of hospitals and emergence of scientific medicine which can delay death, for example survival from a severe head injury.

• Emergence of special institutions to care for ‘the dying’ due mainly to the growth of the hospice movement.

In 2009, there were 220 hospice and palliative care units in the UK providing 3217 beds. Of these, 60 are run by the NHS and 160 are run by the voluntary sector including Sue Ryder Care and Marie Curie Cancer Care (Help the Hospices 2009).

In England, the Department of Health acknowledges the important role hospices and specialist palliative care have in the provision of care by suggesting they are the ‘beacons of excellence in end of life care delivery’ (DH 2008:10). The aim of this strategy has been to look at the main causes of death and consider examples of good practice across the country. It presents some core objectives to achieve high-quality care. These can be summarised as:

• being treated as an individual with dignity and respect

• being without pain and other symptoms

• being in familiar surroundings

The End of Life Care Strategy (DH 2008) builds on the work of the NICE document Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer (NICE 2004) by linking these core objectives to achieving a ‘good death’.

The ethical debates in palliative care

The British Medical Association (2007:3) guidance to medical practitioners states:

One of the most challenging parts of treating a person is to know when to treat and when not to. This is hard for all members of a clinical team, even experienced doctors and nurses. Ethical principles can help us think objectively about making decisions in difficult situations. We will now look at 5 ethical principles, the first 4 were introduced by Beauchamp and Childress in 1977 (Beauchamp and Childress 2009). These principles have been expanded and developed over the years and remains a robust model today.

Final thoughts

The wider concept of end of life care of which palliative care is a part is discussed in more detail in Chapter 16.

Beauchamp T., Childress J. Principles of biomedical ethics, 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

British Medical Association. Withholding and withdrawing life-prolonging medical treatment: guidance for decision making, 3rd ed. Malden: Blackwell; 2007.

Buckley J. Palliative care: an integrated approach. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

Department of Health. End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health; 2008.

Doyle D., Hanks G., Cherney N., Calman K. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Help the Hospices. Hospice and palliative care directory. London: Help the Hospices; 2009.

McSherry W., Ross L. Spiritual assessment in healthcare practice. Keswick: M & K Publishing; 2010.

Narayanasamy A. Spiritual care and transcultural care research. London: Quay; 2006.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guidance on cancer services: improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer: the manual. London: NICE; 2004.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The code: standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives. London: NMC; 2008.

Saunders C. Care of patients suffering from terminal illness at St Joseph’s Hospice, Hackney, London. Nursing Mirror. 1964;14:vii–x.

Sheard D. Being – an approach to life and dementia. London: Alzheimer’s Society; 2007.

Stoll R. The essence of spirituality 1989. In: Carson V.B., ed. Spiritual dimensions of nursing practice. Philadelphia: W B Saunders, 1989.

World Health Organisation. WHO definition of palliative care. Online. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/, 2003. (accessed May 2011)

Becker B. Fundamental aspects of palliative care nursing: an evidence based handbook for student nurses. London: Quay, 2010.

General Medical Council. Treatment and care towards the end of life: good practice to decision making. Online. Available at: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/6858.asp (accessed May 2011)

National Council Palliative Care is an umbrella organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland involved in all aspects of palliative and end of life care. It has a range of publications, news updates and views from government, public and professional groups: http://www.ncpc.org.uk/ (accessed May 2011).

This Website, published by the UK Clinical Ethics Network, provides contact information for UK ethics committees, provides information on ethical issues and links to national policy and guidance: http://www.ethics-network.org.uk (accessed May 2011).

The National End of Life Care Programme Website has up-to-date information and publications on all aspects of end of life care and is a good starting point to search for local and national publications, polices and ways of working: http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/ (accessed May 2011).

healthtalkonline is a charity-run Website that shares patient experiences by facilitating them to tell their own story – many of these stories are presented in short film clips of 1–2 minutes long. You can choose from a variety of headings including receiving bad news, cancer and dying and bereavement: http://www.healthtalkonline.org/ (accessed on 7.5.2011).

St Christopher’s Hospice in London publishes End of Life Care four times per year. This is a journal for nurses who want to deliver the best care for people dying at home, in care homes or in hospital: http://www.stchristophers.org.uk/ (accessed May 2011).

Dementia Care Matters: for more information on the David Sheard approach to meeting spiritual needs. This introduction starts with an interesting video clip: http://www.dementiacarematters.com/ (accessed May 2011).

Answers

Case history 5.1

Possible actions

• Find out who is caring for his dog while he is in hospital.

• Encourage pictures of his dog round the bedside, find out its name, encourage him to talk about it. Why does it have the name it does? How old is it?

• If he has a friend or family member, you might suggest one of them bring in a recent picture of the dog or, even better, a short video clip. Remember, some clinical areas will allow a dog to visit, especially if this is a hospice or specialist palliative care unit.

• The patient may also need to talk about who will look after the dog after he dies.