CHAPTER 16 Principles of Diagnostic Blocks

A critical property of any diagnostic test is that it must be valid. If a test is not valid, the information that it provides will not be correct; the diagnosis will be wrong, and any treatment that ensues will not be appropriate and will probably fail. Along with all other diagnostic tests, diagnostic blocks are subject to this requirement for validity.

VALIDITY

Construct validity

There is a science that involves testing tests. It involves comparing, in the same sample of patients, the results of a test with unknown validity with the results of some other test whose validity is beyond question. That latter test is known as the criterion standard, formerly known as the ‘gold’ standard.

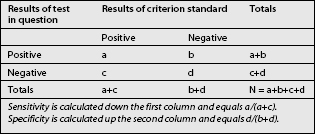

When a test is compared with a criterion standard, the results can be expressed as a contingency table (Table 16.1). Such a table shows the number of patients who have the condition according to the criterion standard, and how many do not; and in how many of each category the test in question was positive or negative. Four cells emerge. The ‘a’ cell is the number of patients in whom the condition is present and in whom the results of the test are positive. These are patients with true-positive responses. The ‘b’ cell contains those patients who do not have the condition but in whom the test was nevertheless positive. These responses are false-positive. The ‘c’ cell represents those patients who have the condition but the test is negative. These responses are false-negative, for the test failed to detect the condition when it should have done so. The ‘d’ cell represents those patients who do not have the condition and in whom the test is negative. The test correctly identified these patients as not having the condition, and their responses are true-negative.

DIAGNOSTIC BLOCKS

There should not be a problem with content validity. All that is required is that the component details of a diagnostic be carefully defined, and that all practitioners of the same block in name correctly execute those details. For this reason, some organizations, such as the International Spine Intervention Society, have formulated definitions and detailed descriptions of certain diagnostic blocks, in order to provide a reference standard.1

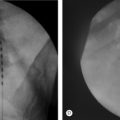

Face validity

In the case of ‘blind’ epidural injections, several limitations have been described. Caudal epidural injections can fail to reach the epidural space in up to 30% or more of injections.2–4 Instead, the injections were behind the sacrum or intravascular. Lumbar epidural injections may fail to reach the epidural space.5 Even when the injectate does reach the epidural space, it does not necessarily flow across the entire space; it can remain in the dorsal epidural space and fail to reach the ventral space.6 For these reasons several investigators have urged that epidural injections should be performed under fluoroscopic control,3,4,7 so that operators can determine whether or not their injectate reached the desired target.

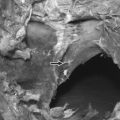

Similarly, it has been shown that the flow of injectate during lumbar medial branch blocks depends on the technique used.8 If needles are placed too far anteriorly on the transverse process, or if the needle is aimed cephalad, injectate can spread to the intervertebral foramen, where it might compromise the specificity of the block. In order to avoid these problems, needles need to be directed slightly caudally, and placed opposite the middle of the neck of the superior articular process.

For procedures such as sympathetic blocks, their face validity remains contentious. For lumbar sympathetic blocks, some operators believe that they can achieve accurate placement of needles simply using surface markings.9 Other operators contend that in order to secure face validity, lumbar sympathetic blocks should be performed under fluoroscopic guidance.10 Only under those conditions can target specificity be secured, in each and every case.

Even classic blocks of the shoulder lack face validity. A study has shown that expert rheumatologists fail to gain access to the glenohumeral joint or the subacromial space in up to 70% of ‘blind’ injections.11

Control blocks

A less rigorous, but more pragmatic, approach is to use comparative blocks. The blocks are performed on separate occasions using local anesthetic agents with different durations of action.9,12–17 Two phenomena are tested: the consistency of response and the duration of response. In the first instance, the patient should obtain relief on each occasion that the block is performed. Secondly, they should obtain long-lasting relief when a long-acting agent is used, but short-lasting relief when a short-acting agent is used. Failure to respond to the second block constitutes inconsistency, and indicates that the first response was false-positive. A response concordant with the expected duration of action of the agent used strongly suggests a genuine, physiologic response. However, lack of concordance does not invalidate the response.

Comparative blocks are confounded by a peculiar property of local anesthetics, particularly lidocaine. Some patients can obtain prolonged effects from lidocaine,16 the basis of which is discussed elsewhere.17 Such prolonged responses do not invalidate the block or the response, provided that the relief is complete. When tested against placebo, comparative blocks prove valid, but to different extents according to the duration of response.18 If the patient reports a concordant response, the chances of the response being false-positive are only 14%. If the responses are complete but prolonged in duration, the chances of a false-positive response are 35%, but in 65% of patients the response is likely to be genuine.

Price et al.19 performed stellate ganglion block on patients with complex regional pain syndromes of the upper limb, using either a local anesthetic or normal saline. They found that normal saline was virtually as effective as local anesthetic in relieving pain and other features. Indeed, there was no significant difference in the incidence of positive responses, or the degree of pain-relief, when the two agents were compared. Similarly, another study showed that the motor features of some patients with presumed complex regional pain syndrome are relieved by placebo infusions.20

DISCUSSION

It is intriguing that there is an imbalance in attitude and demands concerning the validity of diagnostic blocks. Traditional blocks constitute accepted practice, but innovative procedures are subject to criticism and scrutiny. Traditional blocks are excused the requirement for controls, but validation studies are demanded for innovative procedures. Yet ironically, innovative procedures are the most validated procedures in pain medicine, while traditional procedures have not been validated.18

For example, medial branch blocks have been maligned in the literature,21,22 but they have been thoroughly tested for face validity, construct validity, and therapeutic utility. For no other block has this been paralleled.

When performed using the correct technique, lumbar medial branch blocks accurately reach the target nerve, and do not affect any other structure that might confound the response.8 Therefore, lumbar medial branch blocks have face validity. Lumbar medial branch blocks protect normal volunteers from experimentally-induced zygapophyseal joint pain.23 This reinforces their face validity as a test for zygapophyseal joint pain. Single blocks have an unacceptably high false-positive rate of 25–41%.24–26 Given the low prevalence of lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain, this rate means that for every three blocks that appear to be positive, two will be false-positive.24 To be valid, lumbar medial branch blocks have to be performed under controlled conditions. If positive under controlled conditions, lumbar medial branch blocks predict successful outcome following medial branch neurotomy.27 False-negative responses to lumbar medial branch blocks can occur, but are due to inadvertent intravascular injection. This can be detected and avoided if a test dose of contrast medium is injected once the needle is placed. Accordingly, false-negatives are all but eliminated by using contrast medium. As a result, the sensitivity of controlled, lumbar medial branch blocks is virtually 100%.

Cervical medial branch blocks also have proven face validity. Material injected onto the waist of the articular pillar pools in that location, where it infiltrates the target nerve.28 Otherwise, cervical medial branch blocks do not spread to adjacent levels, they do not spread to the spinal nerve, and they do not anesthetize the posterior neck muscles indiscriminately. Single blocks have a false-positive rate of 27%.29 Therefore, to be valid, cervical medial branch blocks must be performed under controlled conditions in each and every case. The construct validity of cervical medial branch blocks has been established, both by statistical methods and by comparing their effects with those of placebo blocks.16,18 Cervical medial branch blocks predict successful outcome from radiofrequency neurotomy. The outcomes are comparable irrespective if placebo-controlled blocks are used or if comparative blocks are used.30,31

1 Bogduk N, editor. Practice guidelines for spinal diagnostic and treatment procedures. San Francisco: International Spine Intervention Society, 2004.

2 White AH, Derby R, Wynne G. Epidural injections for diagnosis and treatment of low-back pain. Spine. 1980;5:78-86.

3 Stitz MY, Sommer HM. Accuracy of blind versus fluoroscopically guided caudal epidural injection. Spine. 1999;24:1371-1376.

4 Renfrew DL, Moore TW, Kathol MH, et al. Correct placement of epidural steroid injections: fluoroscopic guidance and contrast administration. AJNR. 1991;12:1003-1007.

5 Mehta M, Salmon N. Extradural block. Confirmation of the injection site by X-ray monitoring. Anaesthesia. 1985;40:1009-1012.

6 Botwin KP, Natalicchio J, Hanna A. Fluoroscopic guided lumbar interlaminar epidural injections: a prospective evaluation of epidurography contrast patterns and anatomical review of the epidural space. Pain Phys. 2004;7:77-80.

7 El-Khoury G, Ehara S, Weinstein JW, et al. Epidural steroid injection: a procedure ideally performed with fluoroscopic control. Radiology. 1988;168:554-557.

8 Dreyfuss P, Schwarzer AC, Lau P, et al. Specificity of lumbar medial branch and L5 dorsal ramus blocks: a computed tomographic study. Spine. 1997;22:895-902.

9 Buckley FP. Regional anesthesia with local anesthetics. In: Loeser JD, editor. Bonica’s management of pain. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1893-1952.

10 Hanningto-Kiff JG. Sympathetic nerve blocks in painful limb disorders. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of pain. 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:1035-1052.

11 Eustace JA, Brophy DP, Gibney RP, et al. Comparison of the accuracy of steroid placement with clinical outcome in patients with shoulder symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:59-63.

12 Bonica JJ. Local anesthesia and regional blocks. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of pain. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1989:724-743.

13 Bonica JJ, Buckley FP. Regional analgesia with local anesthetics. Bonica, editor. The management of pain, Vol. II.. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, 1990;1883-1966.

14 Boas RA. Nerve blocks in the diagnosis of low back pain. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1991;2:807-816.

15 Bonica JJ, Butler SH. Local anaesthesia and regional blocks. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of pain. 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:997-1023.

16 Barnsley L, Lord S, Bogduk N. Comparative local anaesthetic blocks in the diagnosis of cervical zygapophysial joints pain. Pain. 1993;55:99-106.

17 Bogduk N. Diagnostic nerve blocks in chronic pain. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2002;16:565-578.

18 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Bogduk N. The utility of comparative local anaesthetic blocks versus placebo-controlled blocks for the diagnosis of cervical zygapophysial joint pain. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:208-213.

19 Price DD, Long S, Wilsey B, et al. Analysis of peak magnitude and duration of analgesia produced by local anesthetics injected into sympathetic ganglion of complex regional pain syndrome patients. Clin J Pain. 1998;14:216-226.

20 Verdugo RJ, Ochoa JL. Abnormal movements in complex regional pain syndrome: assessment of their nature. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:198-205.

21 Hogan QH, Abram SE. Diagnostic and prognostic neural blockade. In: Cousins MJ, Bridenbaugh PO, editors. Neural blockade in clinical anesthesia and management of pain. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:837-977.

22 Hogan QH, Abrams SE. Neural blockade for diagnosis and prognosis: a review. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:216-241.

23 Kaplan M, Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, et al. The ability of lumbar medial branch blocks to anesthetize the zygapophysial joint. Spine. 1998;23:1847-1852.

24 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, et al. The false-positive rate of uncontrolled diagnostic blocks of the lumbar zygapophysial joints. Pain. 1994;58:195-200.

25 Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Fellows B, et al. Prevalence of lumbar facet joint pain in chronic low back pain. Pain Phys. 1999;2:59-64.

26 Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Fellows B, et al. The diagnostic validity and therapeutic value of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks with or without adjuvant agents. Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4:337-344.

27 Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, Pauza K, et al. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain. Spine. 2000;25:1270-1277.

28 Barnsley L, Bogduk N. Medial branch blocks are specific for the diagnosis of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. Reg Anesth. 1993;18:343-350.

29 Barnsley L, Lord S, Wallis B, et al. False-positive rates of cervical zygapophyseal joint blocks. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:124-130.

30 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721-1726.

31 McDonald G, Lord SM, Bogduk N. Long-term follow-up of cervical radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:61-68.