Chapter 11 Primary Rhinoplasty

Summary

Introduction

When reviewing the literature, it is readily apparent that the history of rhinoplasty is rooted in the surgeon’s thorough understanding of the three-dimensional nasal anatomy of the nasal region, proficiency in nasal and facial analysis, and firm grasp of the core concepts in manipulating nasal soft tissues, cartilage, and bone.1 Having satisfied these requirements, the surgeon relies on his or her aesthetic sense to craft a result that will produce a balanced, harmonious nose in relationship to the rest of the face.2 The initial operation is critical to the long-term result in primary rhinoplasty, because the tissues are virginal and undistorted by prior operative procedures.

Indications

Patient Selection

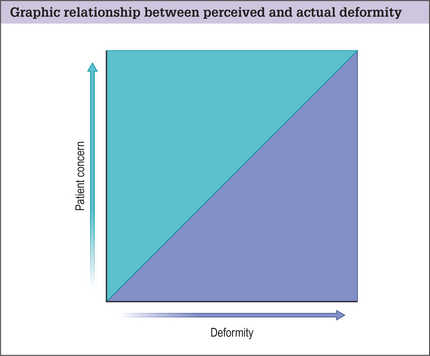

Proper patient selection is vital to a successful outcome. Some patients will likely be dissatisfied regardless of the surgery result. This emotional dissatisfaction often supersedes technical failure as the most common cause of poorly perceived results.

Gunter and Gorney3–5 have both commented on ‘danger signs’ that may be exhibited (Box 11.1). Individuals who meet these criteria should be approached with caution because surgical intervention may not be in the best interests of either the patient or the surgeon.

Similarly, Gorney employs two systems to identify potential problem patients:

Preoperative History and Considerations

Patient Factors

Other red flags in rhinoplasty include:

It should be noted that men tend to have a poorer understanding of their deformity than women and have a more difficult time elucidating the changes they want.6–8

Nasal History

A full and complete nasal history should be obtained. This includes a prior history of:

Anatomic Features

Having determined that the patient is an appropriate candidate for surgery, the next element to proper preoperative surgical planning is critical facial analysis.9,10

Each individual nose has different proportions, morphology, and relative relationships with the surrounding face. To preserve nasofacial harmony, it is crucial to perform a systematic and meticulous analysis of the nose and face. The evaluation is performed in a systematic manner cultivated by the surgeon to assure consistency.11–13

Skin type

The native skin quality influences the operative plan and subsequent techniques performed.

Systematic analysis of the nose and face

Next, a systematic analysis of the nose and face is undertaken.

Look for potential anomalies of the underlying facial skeleton

We divide the face into thirds using horizontal lines adjacent to the:

The upper one-third is the least important because it is the most variable.

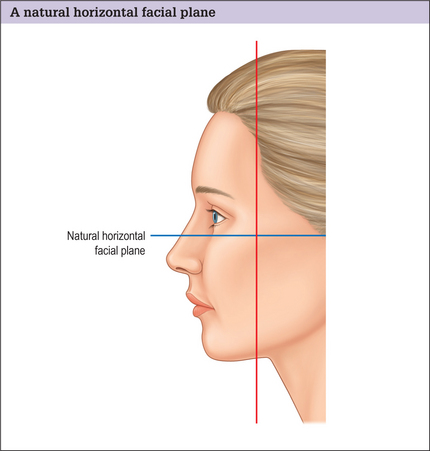

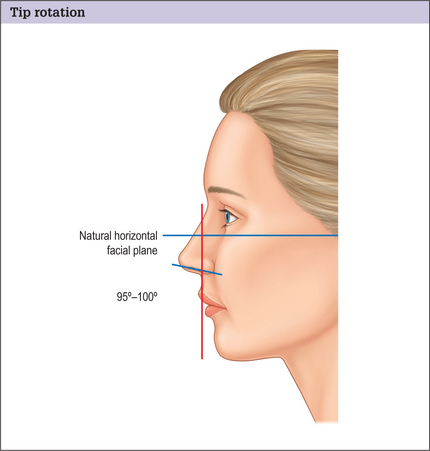

A natural horizontal facial plane is determined by drawing a line perpendicular to a plumb line superimposed over the head in repose and the eyes in straightforward gaze. This will serve as a future point of reference (Fig. 11.2).

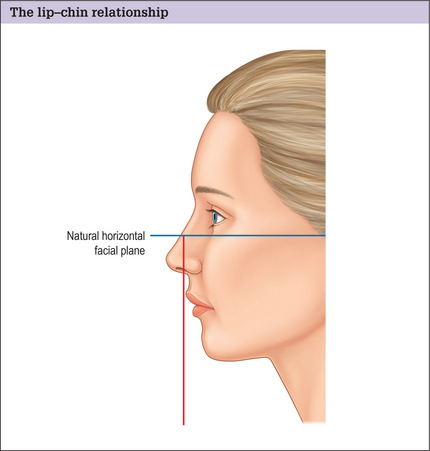

The lip-chin relationship is assessed by dropping a vertical line from a point one-half the ideal nasal length tangential to the vermillion of the upper lip. The lower lip should lie no more than 2 mm behind this line (Fig. 11.3). The ideal chin position is gender dependent. The female chin should be slightly posterior to the lower lip, but equal to the lower lip in men. Discrepancies in these relationships may warrant orthodontics, orthognathic surgery, or a chin implant.

Nasal features

Frontal view

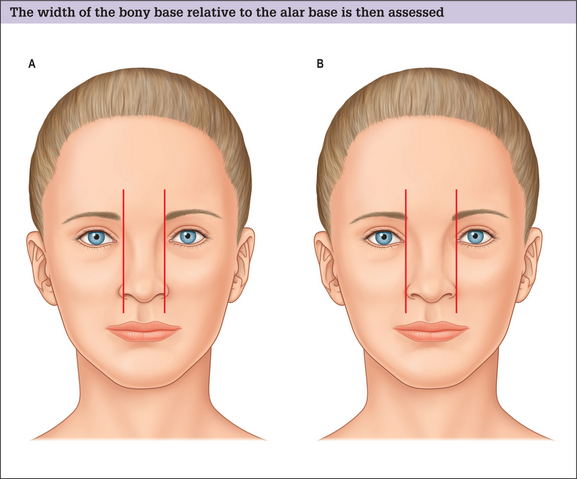

A relationship between the bony base width and the alar base is then assessed. The bony base width should be 80% of the normal alar base width, and a normal alar base width 2 mm wider than the inter-canthal distance, or the width of one eye (Fig. 11.4A&B). If the bony base is greater than 80% of the alar base width (assuming the alar base width is normal), osteotomies will be required to narrow the dorsum. Males tend to have a wider bony base than females and it is important not to over-narrow the male dorsum creating a feminized result.

Next the alar base and alar rim are analyzed. If the alar base width is over 2 mm and greater than the intercanthal distance, it must be determined whether the cause is a narrow intercanthal distance, a true increased interalar width, or alar flaring:

Basal view

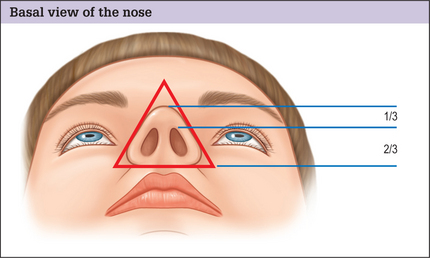

The basal view of the nose is addressed next, with the outline of the nasal base describing an equilateral triangle with a lobule-to-nostril ratio of 1 : 2 (Fig. 11.6). The nostril itself should have a teardrop-like geometry, with the long axis from the base to the apex oriented in a slight medial direction.

Lateral view

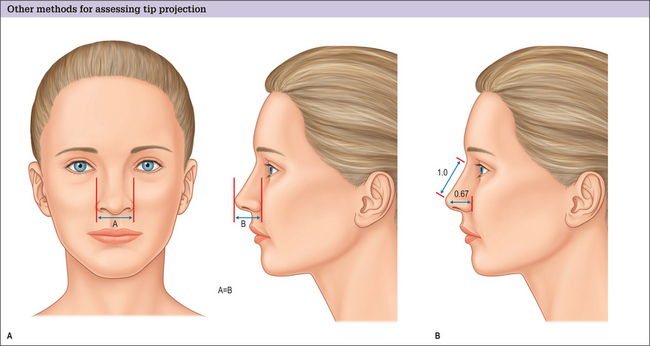

Tip Projection

Tip projection is addressed on the lateral view. We describe two methods to accomplish this.

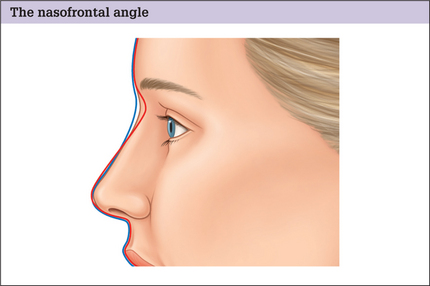

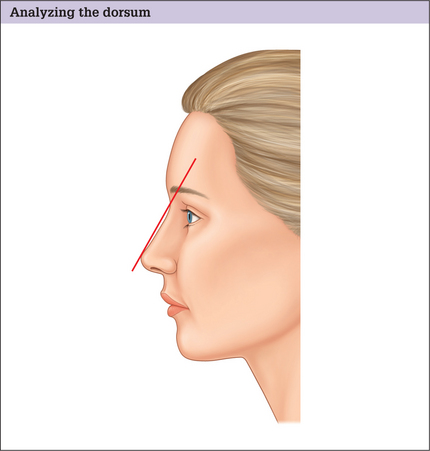

Dorsum

The dorsum is then analyzed. The ideal nasal dorsum should lie approximately 2 mm behind and parallel to a line from the radix to the tip-defining points in women, but should be slightly higher in men to avoid feminizing the nose (Fig. 11.10).

Tip Rotation

The nasolabial angle is used to determine the degree of tip rotation. This angle is obtained by measuring the angle between a line coursing through the most anterior and posterior edges of the nostril and a plumb line dropped perpendicular to the natural horizontal facial plane. This angle should be between 103–105 in women and 95–100 in men (Fig. 11.11).

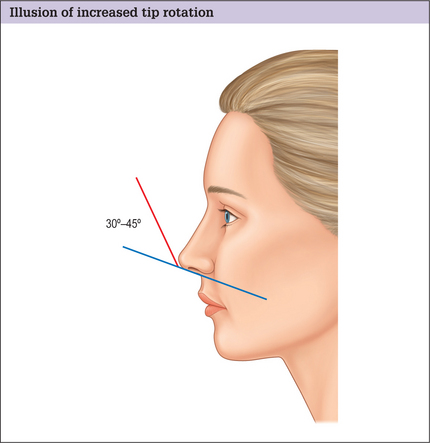

Do not confuse the nasolabial angle with the columellar-labial angle, which is formed at the junction of the columella with the infratip lobule. This angle is normally 30–45 ° (Fig. 11.12). Increased fullness in this area is usually caused by a prominent caudal septum giving the illusion of increased rotation, even though the nasolabial angle is normal.

Alar-columellar relationship (lateral and frontal views)

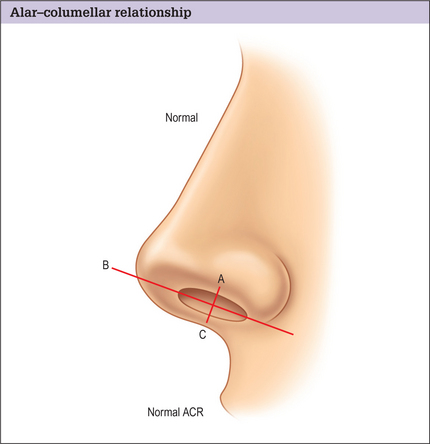

The alar-columellar relationship is then assessed.

A line is drawn through the long axis of the nostril, and a perpendicular line drawn from alar rim to columellar rim that bisects this axis. The distance from the alar rim (point A) to the long axis line (point B) should equal the distance between the long axis line to the columellar rim (point C) if the alar-columellar relationship is normal (Fig. 11.13).

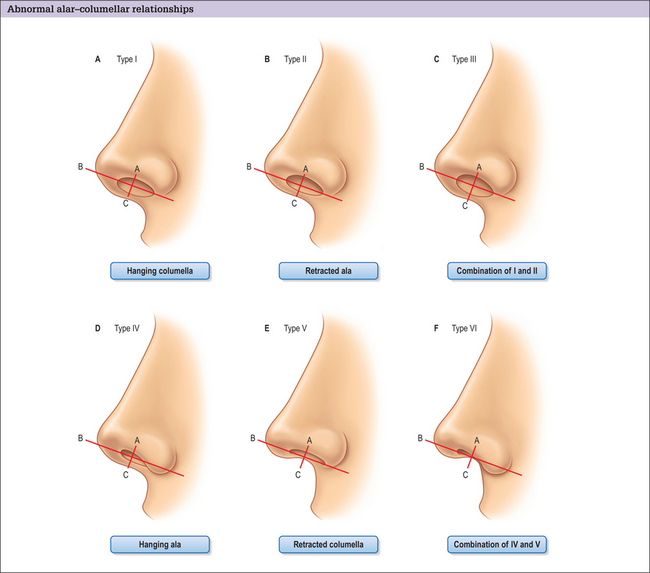

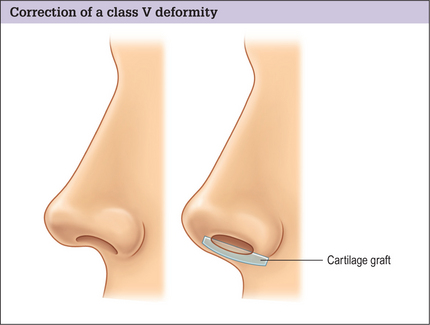

If these measurements are not normal, nasal dismorphology can be categorized into six classes:16,17

Differences between male and female noses

The proportions given above generally apply to Caucasian women. Generally, the male face tends to have a squarer, less rounded appearance, with stronger more pronounced features. The key differences in males are summarized in Box 11.2.7

Box 11.2 Key features of male noses (compared with female noses)*

* These proportions are general guidelines and vary between gender and racial origin. They are only meant to be used as a systematic method of analysis with general proportions and relationships. Each nose should be individualized to the patient’s facial structure and tempered by their desires to create nasofacial harmony and balance.

Intranasal exam

An intranasal exam completes the preoperative analysis. This is performed with a nasal speculum, headlight, and vasoconstriction. The septum, turbinates, and internal nasal valve are evaluated for obvious deformities or pathology. If turbinate hypertrophy is identified, the underlying etiology should be investigated. Turbinate enlargement may be:

Patient Counseling

After the initial history and physical examination, the procedure is fully discussed with the patient. The risks and benefits of the procedure are detailed, and all questions answered. The patient is provided with a written, detailed estimate of surgical charges with complete explanations. It is recommended that patients sign a form accepting financial responsibility. A second clinic visit is encouraged to review the previous discussions. The deformities are reiterated, questions answered, and the consent reviewed and signed. A preoperative instruction sheet and a list of medications to be avoided are also provided (Box 11.3).

Box 11.3 Preoperative instruction sheet

Two weeks before surgery

Morning of surgery

Prior to surgery we convert our operative plan into a graphic re presentation (using Gunter Graphics5) to assist us in the operating room. Modifications to the plan are documented intraoperatively, transposed to the graphic depictions postoperatively, and placed in the patient’s chart for future reference.

Operative Approach

Relevant Anatomy

Skin

The thickness, mobility, and sebaceous character of the nasal skin vary along its length, with the upper two-thirds being thinner, more mobile, and less sebaceous than the inferior one-third.18

Muscles

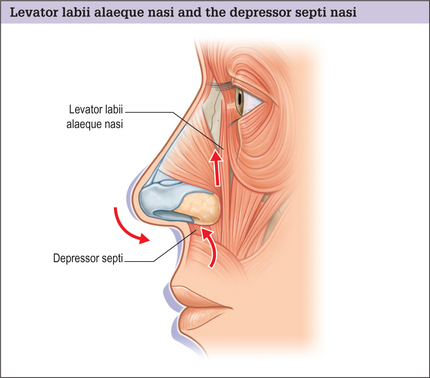

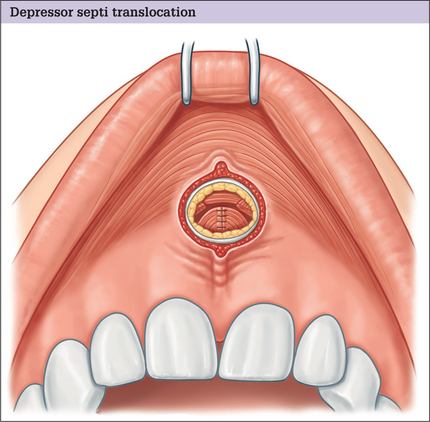

Two muscles, in particular, are important in rhinoplasty:

Evaluation of the depressor septi nasi is routine in our preoperative assessment. Its effect on depressing the nasal tip and shortening the upper lip can be appreciated in some patients on animation (especially when smiling). In the subgroup of patients in whom this muscle significantly alters the nasal appearance, we dissect and transpose the muscle. By doing so, several goals are achieved:

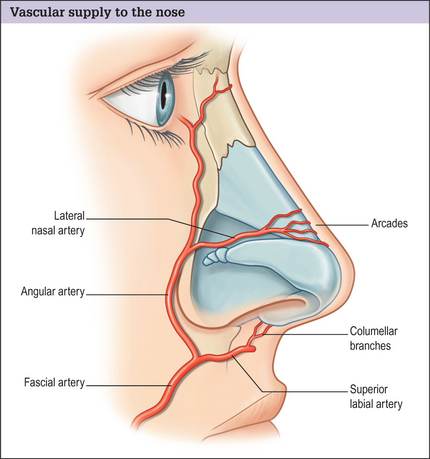

Blood supply

The vascular supply to the nose is derived from branches of the ophthalmic and facial arteries (Fig. 11.16).

Fig. 11.16 Vascular supply to the nose. This is derived from branches of the ophthalmic and facial arteries.

In our 1995 study,21 we found the lateral nasal arteries to be present (either singularly or bilaterally) in 100% of cases, with the columellar branches present 68.2% of the time.

Toriumi et al.22 studied the vascular and lymphatic anatomy of the nose and determined that the transcolumellar incision itself did not compromise major venous or lymphatic outflow. Furthermore, they recommend dissection just above the perichondrium in the deep areolar plane, leaving the musculoaponeurotic layer intact, which preserves the major arterial vascular supply and avoids damage to the venous and lymphatic vasculature that lies in a more superficial (subcutaneous) plane. In this way, bleeding and postoperative edema are minimized.

Nasal vaults

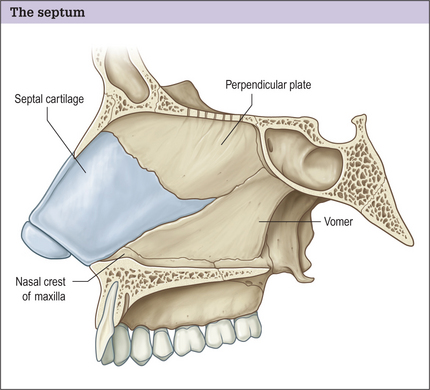

Bony vault

The bony vault (Fig. 11.17) constitutes the upper one-third to one-half of the nose and is made up of the paired nasal bones and the ascending frontal process of the maxilla. It is important to note that the nasal bones are narrowest and thickest above the canthal level. As a result, osteotomies are rarely indicated above this level.

Upper cartilaginous vault

The upper cartilaginous framework begins where the nasal bones overlap the upper lateral cartilages (ULCs) and septum for 4–6 mm, creating what is known as the keystone area. This area should be the widest part of the dorsum, and resembles a T shape in cross-section. The remainder of this vault is comprised of the paired ULCs and dorsal cartilaginous septum. Over-resection during dorsal hump reduction in this area can lead to deformities such as the inverted-V deformity and/or disruption of the dorsal aesthetic lines. A component dorsal septal reduction is advised to avoid these complications.

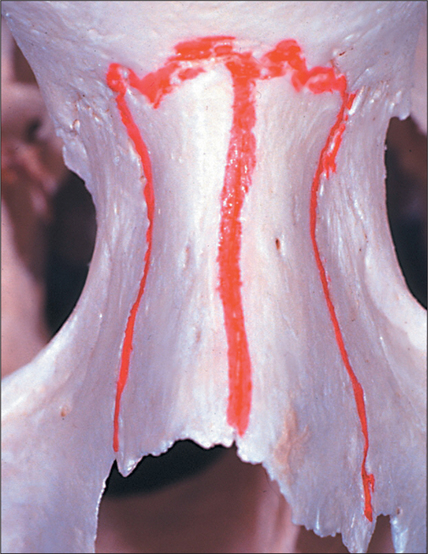

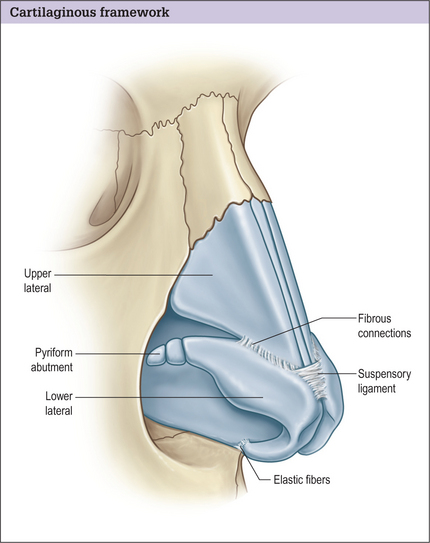

Lower cartilaginous vault

The lower cartilaginous framework begins where the ULCs interdigitate with the lower lateral cartilages (LLCs) in the scroll area. The lower lateral cartilages comprise medial, middle, and lateral crura. These cartilages are connected to each other, the ULCs, and the septum by fibrous tissue and ligaments (Fig. 11.18). Disruption of these ligaments can result in diminished tip projection during rhinoplasty. Therefore if these structures are violated, maneuvers that increase tip support (e.g. columellar struts, extended spreader grafts, batten grafts, suture techniques) may be necessary.

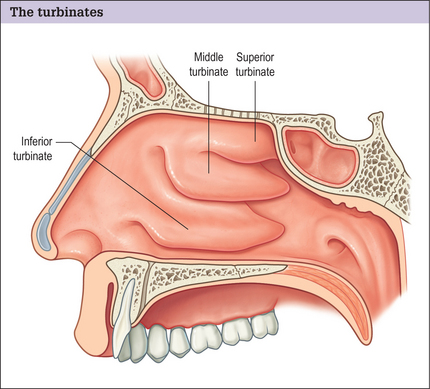

Turbinates

The turbinates (Fig. 11.20) help to guide the transport of air during respiration and condition/humidify inspired and expired air. They are mucosa-lined extensions of the lateral nasal cavity and undergo a normal autonomically mediated cycle of expansion and contraction.

Of all the turbinates, the inferior turbinate has the greatest impact on airway resistance, providing up to two-thirds of total airway resistance from its most anterior aspect.23

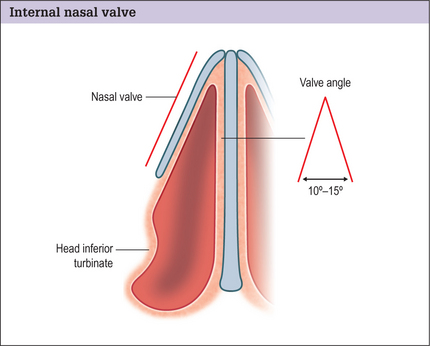

Internal nasal valve

The internal nasal valve (Fig. 11.21) can contribute up to 50% of the total airway resistance and is the narrowest segment of the nasal airway. It is composed of the angle formed by the intersection of the nasal septum and the caudal margin of the ULC, and is usually 10–15 °.24,25

In some cases, the anterior portion of the inferior turbinate may be a significant contributor to the decrease in the cross-sectional area of this region.26

Incisional Approaches

The two basic incisional approaches to rhinoplasty are:

Each has its advocates who use them successfully in the practice of rhinoplasty.

Open versus closed approach

Most of our cases involve the open approach because it:

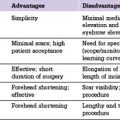

There are advantages and disadvantages to both rhinoplasty techniques (Table 11.1), but the correct approach is dictated by the patient’s anatomic deformity and the surgeon’s experience. Clearly, what is performed to alter the underlying anatomy is far more important than the type of incision used.

Table 11.1 Relative advantages of open vs closed (endonasal) technique.

| Open technique | Closed technique | |

|---|---|---|

| Binocular visualization | +++ | ++ |

| Evaluation of deformity without distortion | +++ | + |

| Precise diagnosis and correction of deformities | +++ | + |

| Direct control of bleeding | ++ | + |

| Nasal incision | + | +++ |

| Operative time | + | ++ |

| Prolonged nasal tip edema | + | +++ |

The open approach provides full visualization of the nasal framework to more accurately diagnose the cause of the nasal airway obstruction or the cosmetic deformity. The manipulation of the various structures, including the dorsum, septum and the tip, can be done with precision and can yield predictable results. We strongly recommend the open approach when addressing a posttraumatic deformity, cleft lip nose deformity, in secondary/revisional surgery, or when complex tip modifications are necessary (Box 11.4).27

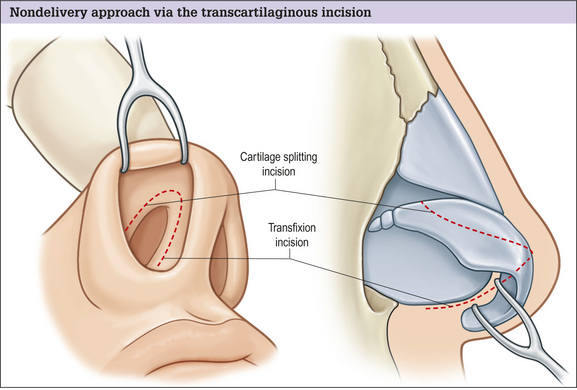

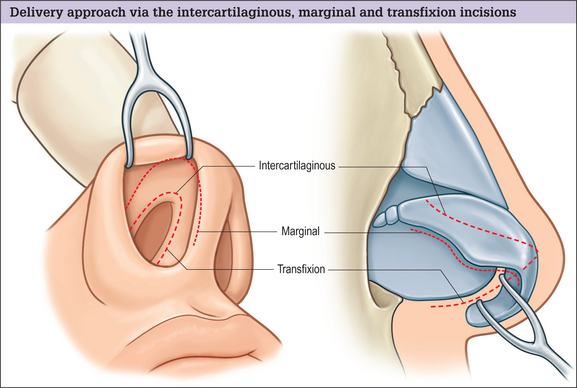

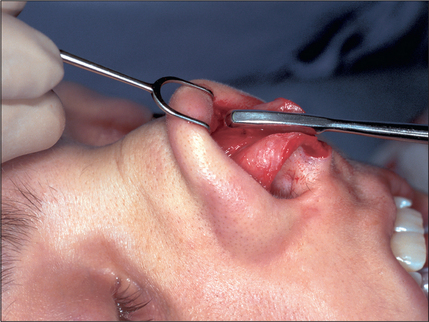

1 mm cephalad to the caudal margin of the lateral crus). We combine this with an intercartilaginous incision in cases of minor tip refinement to allow for adequate cartilage delivery and exposure. If the caudal septum also needs to be addressed, we perform a concomitant hemitransfixion or transfixion incision (Box 11.5).

Operative Technique

Preparation for surgery

Table 11.2 Location/volume distribution of 1% lidocaine with 1 : 100 000 epinephrine.

| Location | Amount (mL) |

|---|---|

| Vestibules/aperture | 2 |

| Dorsum | 1 |

| Lateral walls | 2 |

| Tip/columella | 2 |

| Distal septum | 2 |

| Inferior turbinates | 1 |

| Total | 10 |

Incision

Closed approach

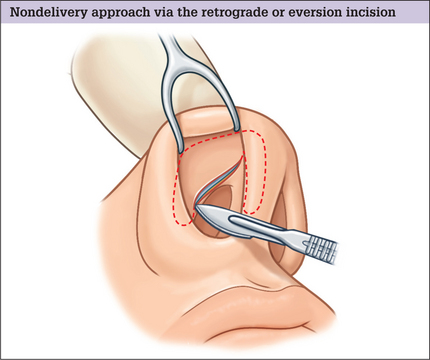

Nondelivery approach

The nondelivery approach uses either a transcartilaginous (cartilage splitting) incision or a retrograde or eversion incision.

Transcartilaginous Incision

Retrograde Approach

Delivery approach

Open approach

Skin envelope dissection

Reducing the osteocartilaginous hump

Separation of the ULCs from the septum

Incremental component cartilaginous dorsal septal reduction

Incremental dorsal bony reduction

Three-point dorsal palpation test

Septal reconstruction/cartilage graft harvest

Cephalic trim

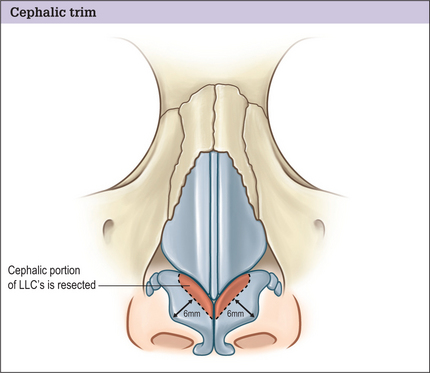

When the tip is boxy or bulbous and requires better refinement and definition, if the tip-defining points need medialization, or when rotation of the tip is desired, a cephalic trim (Fig. 11.28) is performed. This is done by using a caliper to measure along the caudal margin of the lower lateral cartilage to preserve a 6 mm rim strip. After this is demarcated, the cephalic portion of the middle and lateral crura is resected.

Fig. 11.28 A cephalic trim of the lateral crura cartilage is performed for nasal tip refinement and definition.

The cartilage is preserved for possible use later in the case.

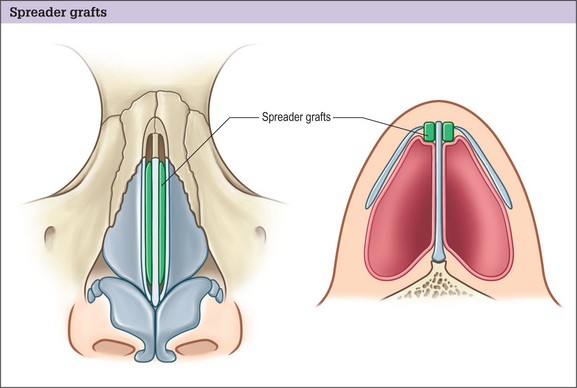

Spreader grafts

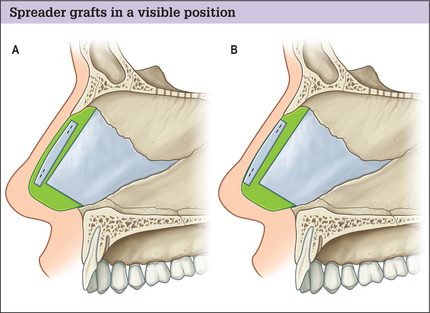

Failure to preserve the middle vault can result in collapse of the internal nasal valve as well as cosmetic deformity, such as the inverted V or saddlenose deformity. In this situation, spreader grafts (Fig. 11.29) can be used to help stent open the internal valve, stabilize the septum, and preserve the dorsal aesthetic lines.28,29,31 These grafts are usually obtained from septal cartilage, and are designed to measure approximately 25–30 mm by 3 mm. Their cephalic ends can be trimmed obliquely to fit snugly underneath the bony dorsum and their caudal ends can be placed either at:

Furthermore, the grafts can be placed in a visible position (secured in a higher position along the septum) or in an invisible position (positioned lower) (Fig. 11.30). We secure the grafts with 5–0 PDS in horizontal mattress fashion.

Tip modification

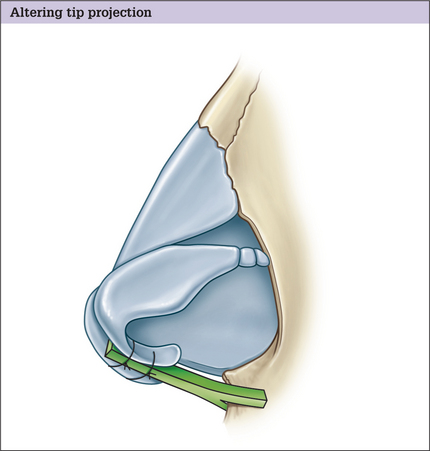

Altering tip projection

It is important to recognize the factors that contribute to tip projection in situ before embarking on a discussion on how to precisely alter tip projection.27,32 There are six key anatomic elements to tip projection (Box 11.6). Alteration of any of these anatomic structures can result in incremental changes in tip projection.

The algorithm begins with suture techniques,33 which are able to achieve an increase of 1–2 mm of tip projection. Suture techniques are ideal for controlling cartilage in a precise, nondestructive fashion. Although the choice of particular suture material is surgeon dependent, the underlying premise is to choose a material that one can easily work with that will hold the cartilage in its altered position long enough to allow for the natural fibrotic reaction to solidify the result. Although many suture techniques can be performed in both open and closed rhinoplasty (with cartilage delivery), we find them easier to place using the open method, because it affords greater visualization and ease of placement.

The four general types of suture technique used to alter projection are:

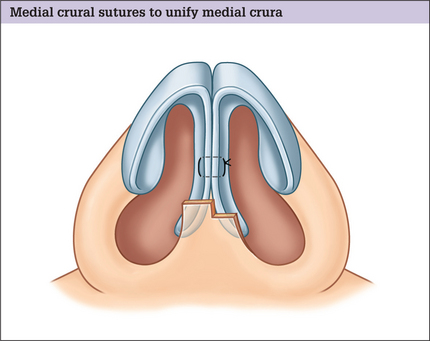

Medial crural sutures

Medial crural sutures (Fig. 11.31) unify the medial crura of the lower lateral cartilages and are often used in conjunction with a columellar strut (to help stabilize the strut). They can also be used to straighten out flaring of the medial/middle crura (either on the caudalmost aspect or near the domal area), thereby effecting an increase in projection, albeit to a limited degree. We generally use 5–0 PDS suture in horizontal mattress fashion for this technique, but the suture choice can vary by individual preference.

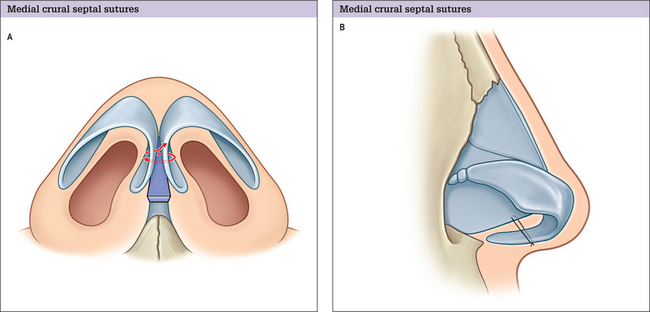

Medial crural septal sutures

Medial crural septal sutures (Fig. 11.32) anchor the medial crura to the caudal septum, and can alter projection as well as rotation. They are often used in conjunction with columellar struts. We frequently use 5–0 clear nylon suture in spanning fashion for this technique.

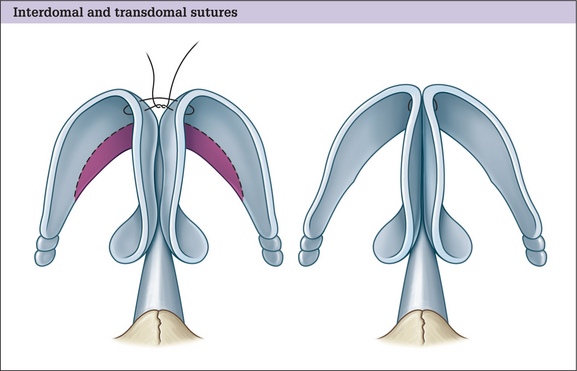

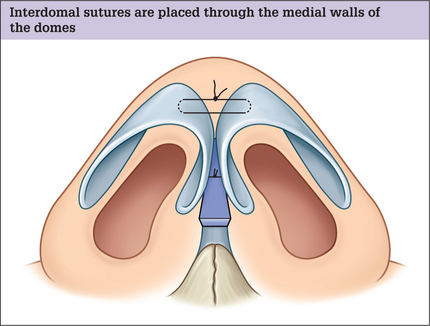

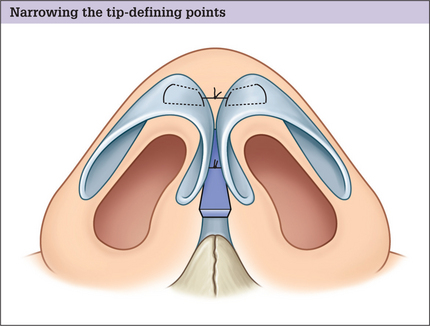

Interdomal sutures

Interdomal sutures (Figs 11.33 and 11.34) are placed through the medial walls of the domes in mattress fashion and are tied so as to narrow the interdomal distance. This results an increase in both tip refinement and projection.

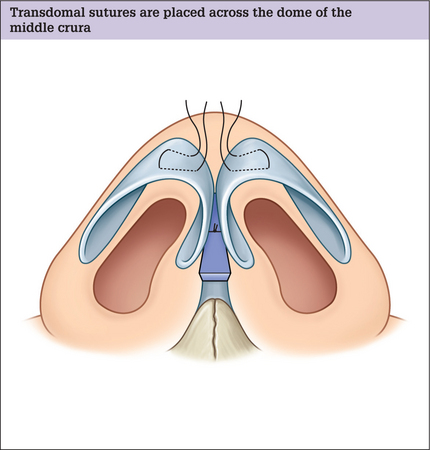

Transdomal sutures

Transdomal sutures (Figs 11.35 and 11.36) are placed across the dome of the middle crura in mattress fashion, such that the vestibular skin is not perforated. Local anesthetic can be used to hydrodissect a plane between the cartilaginous dome and the adherent underlying mucoperichondrium to help prevent inadvertent incorporation into the suture bite. We generally use 5–0 PDS in horizontal mattress fashion and leave the knots on the medial aspect of the dome.

Fig. 11.36 Transdomal sutures are tied together in spanning fashion to narrow the tip-defining points.

Transdomal sutures can be made:

It is important to prevent overtightening of this suture, which can result in an unnaturally sharp tip-defining point.

Placement of a columellar strut

The next step in altering tip projection involves the placement of a columellar strut, which:

Medial crural sutures (see above) are placed in horizontal mattress fashion to secure the complex. Further medial crural sutures can be placed more caudally on the medial crura to control flaring, if necessary.

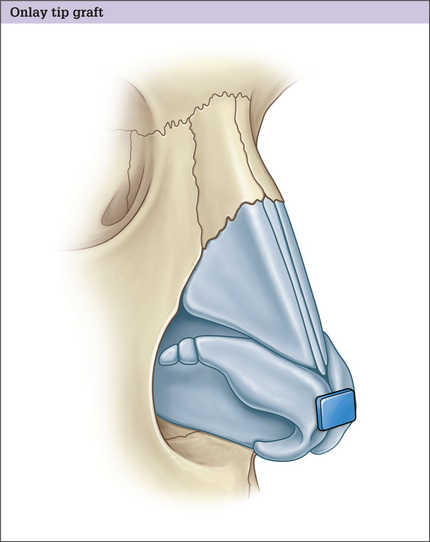

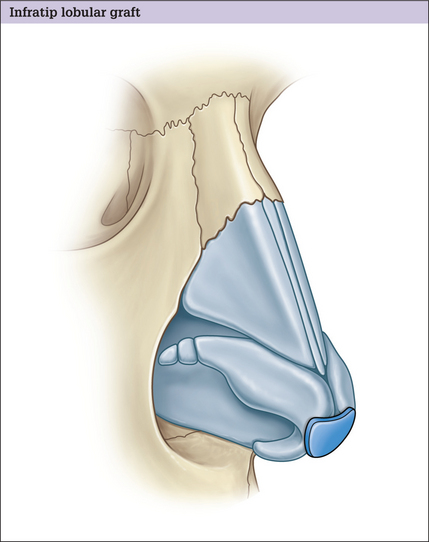

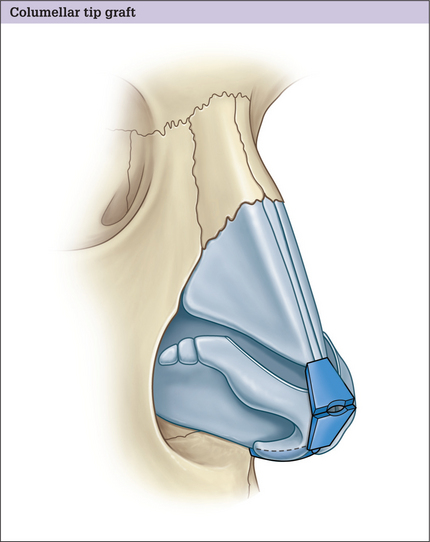

Tip grafts

If more tip projection or definition is desired after the preceding maneuvers, tip grafts may be used. We find it easier to place these grafts using the open approach because it allows excellent visualization, precise placement, and facilitates subsequent manipulation, if necessary. Grafts in general have a tendency to be visible, however, so their use is reserved only for the patient in whom the prior, more predictable methods do not result in satisfactory tip projection. There are three general types of tip grafts (Box 11.7):

Box 11.7 The three general types of tip graft

Onlay tip graft (see Fig. 11.39)

Infratip lobular graft (see Fig. 11.40)

Altering tip rotation

Using the nasofacial analysis techniques described, rotation is evaluated generally by the nasolabial angle. This angle, found by measuring the angle between a line coursing through the most anterior and posterior edges of the nostril and a plumb line dropped perpendicular to the natural horizontal facial plane, should be between 95 and 100 ° in women and between 90 and 95 ° in men (see Fig. 11.11).

When changing tip rotation, the extrinsic forces holding the tip at its current angle must be released. This is generally done by severing the connection between the lower and upper lateral cartilages. This frequently takes the form of a cephalic trim, as described above. Furthermore, the fibrous attachments of the medial crura and the caudal septum can be transected to release tension on the nasal tip and allow for more cephalad rotation. This is generally achieved by resecting a variable amount of the caudal septum (Fig. 11.42). This maneuver can also affect tip projection.

Correcting the alar-columellar relationship

Class I deformity

When a class I deformity exists (see Fig. 11.14A), or when the long axis-columellar rim distance (BC) is greater than 2 mm and the alar rim-long axis distance (AB) is normal, that is an example of a true hanging columella.

Correcting this involves resecting either the caudal septum, the caudal portion of the medial crus, the caudal portion of the middle crus, or a combination of these – whichever is responsible for the deformity (Fig. 11.42).

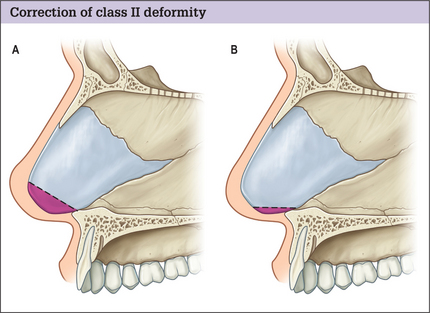

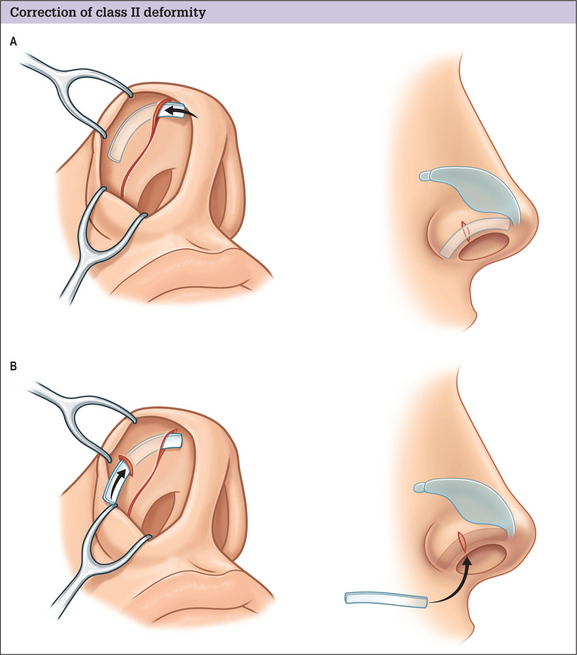

Class II deformity

A class II deformity (see Fig. 11.14B) or a retracted ala (AB > 2 mm, BC < 2 mm) can be treated in several ways:

Class III deformity

A class III deformity (see Fig. 11.14C) is a combination of a class I and class II deformity, and is corrected with a combination of the procedures outlined above to correct class I and class II deformities.

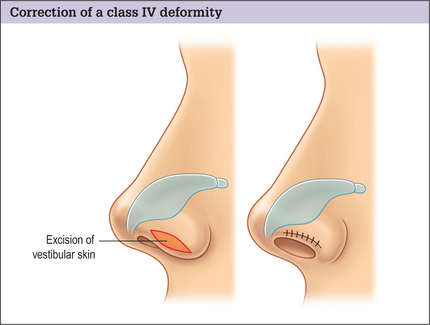

Class IV deformity

A class IV deformity (see Fig. 11.14D) is a hanging ala (AB < 1 mm, BC < 2 mm).

This is usually treated with an elliptical excision of vestibular skin (Fig. 11.44). Care is taken to avoid over-resection of skin because an abnormal, rolled-in appearance of the alar rim can result.

Osteotomy Techniques

Osteotomies are a powerful technique in rhinoplasty.34–36 The indications to perform osteotomies, regardless of technique are:

Contraindications to osteotomies can include:

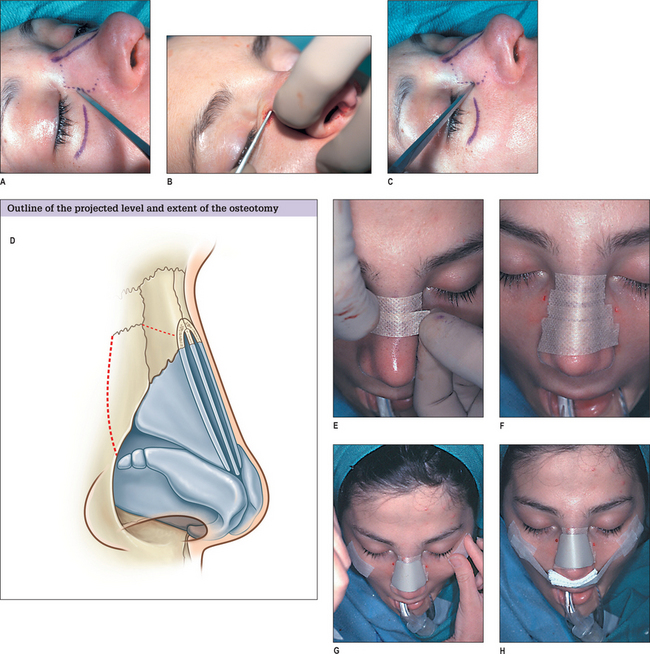

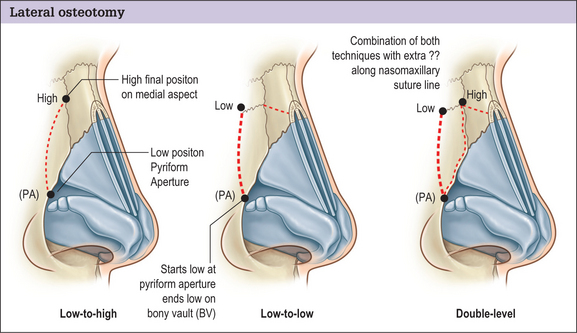

There are several osteotomy techniques, including medial, lateral, transverse, or a combination of these. Furthermore, they can be performed through either an external or internal approach37–39 (Figs 11.46 and 11.47).

Fig. 11.46 Lateral osteotomy. This may be performed as ‘low to high,’ ‘low to low,’ or as a double level.

A lateral osteotomy may be performed as ‘low to high’, ‘low to low’, or as a double level (Fig. 11.46) and may be combined with medial, transverse, or greenstick fractures of the upper bony segment.

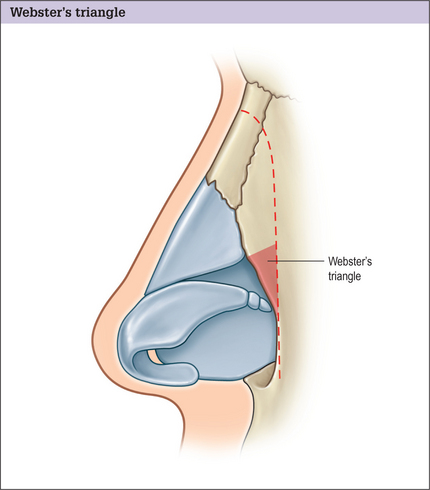

No matter how the osteotomy is performed, however, it is necessary to preserve Webster’s triangle (Fig. 11.47), which is a triangular area of the caudal aspect of the maxillary frontal process near the internal valve. Preserving this area maintains support to the valve and prevents functional nasal airway obstruction from collapse.

‘Low to low’ osteotomy

It starts low along the piriform aperture and continues low along the base of the bony vault to end in a lateral position along the dorsum near the intercanthal line.

Our technique of external perforated lateral osteotomy

The unique advantages of this technique are based on the preservation of the periosteal attachments,40 namely:

Procedure

Our technique is as follows (Figs 11.48A-H).

Medial osteotomies

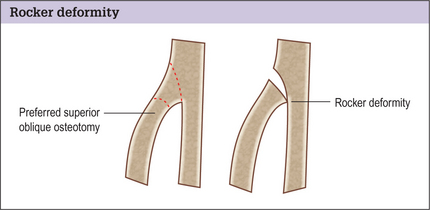

Medial osteotomies are used to facilitate medial positioning of the nasal bones. They are generally indicated in patients with thick nasal bones or a wide bony base to achieve a more predictable result; greenstick fractures in these subgroups can sometimes be difficult and can lead to unpredictable fracture patterns.41

Medial osteotomy used in conjunction with lateral osteotomy

Furthermore, it is paramount to avoid placing the medial osteotomy too far centrally as it connects with the lateral osteotomy causing a rocker deformity, where the upper portion of the fractured nasal bone ‘kicks out’, resulting in a widened upper dorsum (Fig. 11.49). This can be avoided by following an oblique angle.

Closure

The transcolumellar incision is then closed using 6–0 nylon suture in simple interrupted fashion, making sure the coaptation of the incision margins is precise (Fig. 11.50A&B). The stairstepping of the original incision helps us close this accurately.

The nasal dorsum is then carefully taped, and a malleable metal splint is applied over the dorsum (Figs 11.51).

Fig. 11.51 The nasal dorsum is carefully taped, and a malleable metal splint is applied over the dorsum.

A drip pad is fashioned from a gauze 2 × 2 and secured under the nose with paper tape. The throat pack is removed, and the oropharynx and stomach are carefully suctioned to help evacuate any blood that may result in postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Alar Base Surgery

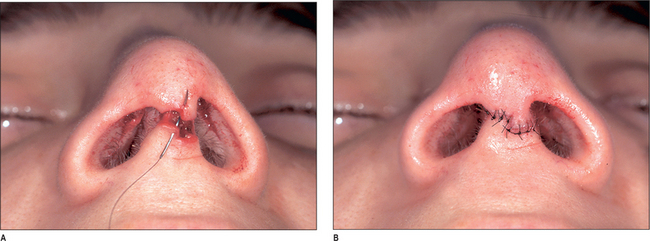

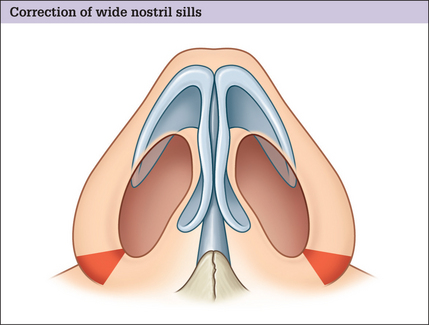

Wide nostril sills

Wide nostril sills (or alar flaring) is relatively common. It is corrected by performing a small crescentic resection of the alar base, making sure to avoid extending the incision into the actual vestibule (Fig. 11.52). The incision is placed approximately 1–2 mm above the base to prevent alar notching. The soft tissue at the base is mobilized with judicious use of electrocautery and transposed medially to the desired aesthetic endpoint, where it is sutured in place. We suture using the ‘halving principle’ in this region, because the interior incision is shorter than the exterior incision.

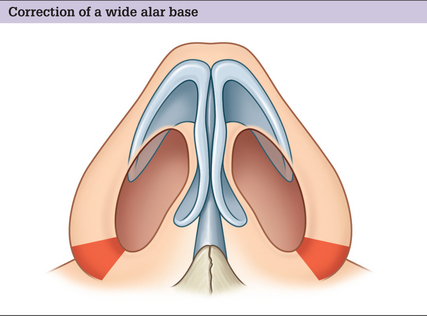

Wide alar base

A wide alar base is corrected in a similar fashion, but the crescentic excision assumes a more wedge-type geometry and may include a small portion of the nostril sill (Fig. 11.53). If a transcolumellar incision was used at the start, it is crucial that the alar base excision stays within 3 mm of the lateral alar groove because the blood supply to the nasal tip can be jeopardized if the lateral nasal artery is inadvertently injured. Although some have advocated suture techniques for narrowing the nasal base, we generally perform this with excisional techniques.

Depressor Septi Translocation

Optimizing outcomes

Complications and Side Effects

In the author’s (RJR) practice, approximately 1 in 30 primary rhino-plasty patients requires revision. The most frequent reasons for reoperation include:

Rare complications include anosmia and lachrymal duct injury.

Complications of lateral nasal osteotomies are listed in Box 11.8.

Postoperative Care

All preoperative and postoperative instructions are given to the patients in writing before and on the day of surgery. Postoperatively, we routinely prescribe:

Cool compresses are used periorbitally during the day for the first 48 hours.

1. Sheen J.H., Sheen A.P. Aesthetic rhinoplasty, 2nd edn. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing, 1998.

2. Loomis A. Drawing the head and hands. New York: Viking Press, 1956.

3. Gorney M. Criteria for patient selection: an ounce of prevention. Presented at the Senior Resident’s Conference Risk Management Course. 1996. Dallas

4. Gorney M. Patient selection in rhinoplasty: patient selection. In: Daniel R.K., editor. Aesthetic plastic surgery: rhinoplasty. Boston: Little Brown, 1993.

5. Gunter J.P. Rhinoplasty. In Courtiss E.H., editor: Male aesthetic surgery, 2nd edn, St Louis: Mosby, 1990.

6. Daniel R.K. Rhinoplasty and the male patient. Clin Plast Surg. 1991;18:751-761.

7. Rohrich R.J., Janis J.E., Kenkel J.M. Male rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1071-1085. discussion 1086

8. Wright M.R. The male aesthetic patient. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:724-727.

9. Gunter J.P., Hackney F.L. Clinical assessment and facial analysis. In: Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, editors. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2002:53.

10. Rohrich R.J., Gunter J.P., Shemshadi H. Facial analysis for the rhinoplasty patient. Dallas Rhinoplasty Symp. 1996;13:67.

11. Byrd H.S., Hobar P.C. Rhinoplasty: a practical guide for surgical planning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:642-654. discussion 655–656

12. Daniel R.K., Lessard M.L. Rhinoplasty: a graded aesthetic–anatomical approach. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;13:436-451.

13. Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, Gunter J.P. Advanced rhinoplasty anatomy. In: Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, editors. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2002:8.

14. Guyuron B. Dynamics of rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88(6):970-978.

15. Guyuron B. Cosmetic follow-up: dynamics in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(6):2257-2259.

16. Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Friedman R.M. Classification and correction of alar–columellar discrepancies in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:643-648.

17. Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Friedman R.M., et al. Importance of the alar–columellar relationship. In: Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, editors. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing, 2002.

18. Gonzalez-Ulloa M., Stevens E., Alavarez Fuertes G., et al. Skin thickness. Diagn Med. 1961;33:1880-1896. Report of our microscopic study of the total surface of the face and body

19. Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, Huynh B., et al. Importance of depressor septi muscle: an anatomic study and clinical application. In: Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, editors. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2002:849.

20. Rohrich R.J., Huynh B., Muzaffar A.R., et al. Importance of the depressor septi nasi muscle in rhinoplasty: anatomic study and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:376-383. discussion 384–38

21. Rohrich R.J., Gunter J.P., Friedman R.M. Nasal tip blood supply: an anatomic study validating the safety of the transcolumellar incision in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:795-799. discussion 800–801

22. Toriumi D.M., Mueller R.A., Grosch T., et al. The lateral nasal artery and blood supply to the nasal tip. In: Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, editors. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2002:20.

23. Rohrich R.J., Krueger J.K., Adams W.P., et al. Rationale for submucous resection of hypertrophied inferior turbinates in rhinoplasty: an evolution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:536-542. discussion 545–546

24. Kasperbauer J.L., Kern E.B. Nasal valve physiology. Implications in nasal surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1987;20:699-719.

25. Haight J.S., Cole P. The site and function of the nasal valve. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:49-55.

26. Pollock R.A., Rohrich R.J. Inferior turbinate surgery: an adjunct to successful treatment of nasal obstruction in 408 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:227-236.

27. Adams W.P.Jr, Rohrich R.J., Hollier L.H., et al. Anatomic basis and clinical implications for nasal tip support in open versus closed rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:255-261. discussion 262–264

28. Rohrich R.J., Hollier L.H. Rhinoplasty – dorsal reduction and spreader grafts. Dallas Rhinoplasty Symp. 1999;16:153.

29. Rohrich R.J., Hollier L.H. Use of spreader grafts in the external approach to rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23:255-262.

30. Rohrich R.J., Muzaffar A.R., Janis J.E. Component dorsal hump reduction: the importance of maintaining dorsal aesthetic lines in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1298-1308. discussion 1309–1312

31. Sheen J.H. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:230-239.

32. Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, Deuber M.A. Graduated approach to tip refi nement and projection. In: Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, editors. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2002:333.

33. Gruber R.P. Suture techniques. In: Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, editors. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2002:254.

34. Goldfarb M., Gallups J.M., Gerwin J.M. Perforating osteotomies in rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:624-627.

35. Parkes M.L., Kamer F., Morgan W.R. Double lateral osteotomy in rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol. 1977;103:342-348.

36. Sullivan P.K., Harshbarger R.J., Oneal R.M. Nasal osteotomies. In: Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, editors. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2002:595.

37. Rohrich R.J., Janis J.E., Adams W.P., et al. An update on the lateral nasal osteotomy in rhinoplasty: an anatomic endoscopic comparison of the external versus the internal approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:2461-2462. discussion 2463

38. Rohrich R.J., Krueger J.K., Adams W.P., et al. Achieving consistency in the lateral nasal osteotomy during rhinoplasty: an external perforated technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:2122-2130. discussion 2131–2132

39. Rohrich R.J., Krueger J.K., Adams W.P.Jr. Importance of lateral nasal osteotomy: an external perforated technique. In: Gunter J.P., Rohrich R.J., Adams W.P.Jr, editors. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2002:615-631.

40. Ford C.N., Battaglia D.G., Gentry L.R. Preservation of periosteal attachment in lateral osteotomy. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;13:107-111.

41. Harshbarger R.J., Sullivan P.K. Lateral nasal osteotomies: implications of bony thickness on fracture patterns. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42:365-370. discussion 370–371