Chapter 23 Primary Retroperitoneal Tumors

Introduction

Primary retroperitoneal tumors are an exceedingly rare clinical problem. Masses in the retroperitoneum can be categorized as one of three entities: lymphomas, extragonadal germ cell tumors, and sarcomas. Although gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) arise in the intraperitoneal compartment, they can also mimic these retroperitoneal masses because of their large size. This chapter deals with primary retroperitoneal sarcomas (RPSs), which form about one third of all retroperitoneal tumors. Lymphomas, extragonadal germ cell tumors, and GISTs are discussed in Chapters 16, 20, and 29. RPSs generally lack specific clinical symptoms beyond the effect manifested from their mass or impact on adjacent organs. As a result, they progress to a very large size before the patient seeks medical care. Their successful management requires the collaborative efforts of the radiologist, pathologist, radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, surgical oncologist, and other specialists. Imaging plays a key role in the detection, planning of therapy, and follow-up of these patients.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Soft tissue sarcomas (STSs) form 1% of all newly diagnosed malignancies in the United States and 15% of these arise in the retroperitoneum.1 STSs in children account for up to 15% of all pediatric malignancies. The mean annual incidence of RPS is 2.7 per million persons and no significant change has been observed in a recent review encompassing 29 years of data.2

Exposure to ionizing radiation increases the incidence of STSs, with a median interval of 10 years (range 2-50 yr) after exposure. These occur in the irradiated field commonly in patients who receive radiation therapy for breast, cervical cancer, lymphoma, and testicular tumors or for benign conditions.3–5 Patients treated with prior radiation exposure can develop either STSs or bone sarcomas.

Several genetic syndromes are associated with the development of STS.6 Neurofibromatosis type 1, or von Recklinghausen’s disease, is an autosomal dominant condition that is due to a mutation in the NF1 gene. These patients have a high incidence of neurofibromas as well as approximately a 10% increased risk of developing malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors during their lifetime. Gardner’s syndrome, another autosomal dominant disease, is caused by mutation of the APC gene and associated with multiple colonic polyps, colon cancer, and desmoid tumors. STS has also been reported in patients with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome, caused by a germline mutation in the p53 tumor-suppressor gene. Children with hereditary retinoblastoma due to a germline mutation in the RB1 tumor-suppressor gene face a higher risk of STS and osteosarcoma. The risk is further increased because these patients receive radiotherapy for the initial treatment of retinoblastoma.

Anatomy and Pathology

Anatomy

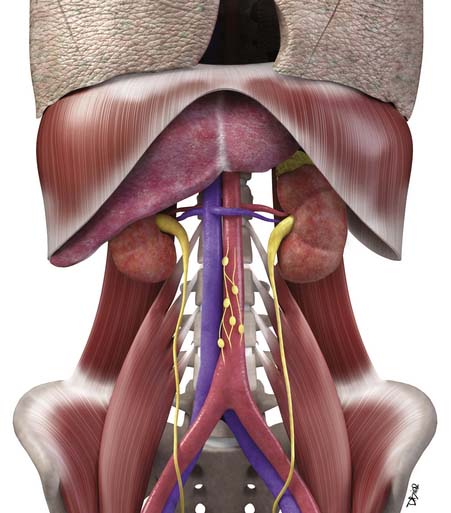

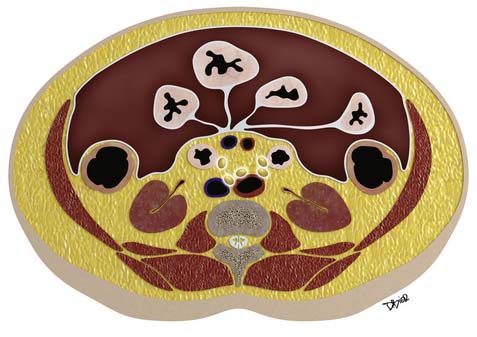

Macroscopically, parts of the genitourinary tract, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, aorta and its branches, inferior vena cava and its tributaries, and lymphatic and nervous systems form important components of the retroperitoneum (Figure 23-1). The pancreas, ascending colon, descending colon, and duodenum are located anteriorly within the anterior pararenal space (APS), and the aorta, inferior vena cava, and lymph nodes are in the midline. Laterally, the kidneys and adrenals are surrounded by renal fascia within the perirenal space (PS). The psoas, quadratus lumborum, paraverterbral muscles, and bony skeleton form the posterior boundary of the retroperitoneum. Retroperitoneal fat, vessels, lymphatics, and nerves continue from the retroperitoneum into the small bowel mesentery, providing anatomic continuity between these compartments (Figure 23-2). The displacement or contiguous involvement of these major organs, and in particular of the major vascular branches, is of critical importance when planning surgical resection.

Key Points Anatomy

• Duodenum, ascending and descending colon, and pancreas lie anteriorly in the APS.

• Kidneys and adrenals surrounded by renal fascia laterally lie within the perirenal space.

• Muscles and bones form the posterior boundary of the retroperitoneum.

• Arterial encasement, venous involvement, and the displacement or invasion of adjacent organs are important considerations in surgical planning.

Pathology

Microscopically, primary sarcomas can arise from fat, smooth or skeletal muscle, fibrous connective tissue, peripheral nerve cells, vascular tissue, or other mesenchymal cells (Table 23-1). STSs are classified according to the adult cell type that the tumor cells most closely resemble. However, this does not mean that the tumor arose from that cell type. The use of immune markers provides important additional information in the classification of STS. Liposarcomas are the most common type of tumor in adults, followed by leiomyosarcoma.7 In the older reports, the category of “malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH)” was common, whereas in current series, it is distinctly uncommon and classified instead as “undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.”8 Ten percent to 15% of all sarcomas occur in children. In reviews from single institutions, the most common retroperitoneal sarcoma in the pediatric age is rhabdomyosarcoma, followed by fibrosarcoma and liposarcoma.9,10

Table 23-1 World Health Organization Classification of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

| Adipocytic Tumors |

| Atypical lipomatous tumor (ALT)/well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDLPS) |

| Dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLPS) |

| Myxoid/round cell liposarcoma |

| Pleomorphic liposarcoma |

| Smooth Muscle Tumors |

| Leiomyosarcoma |

| Skeletal Muscle Tumors |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma (embryonal, alveolar, and pleomorphic) |

| Fibroblastic/Myofibroblastic Tumors |

| Fibrosarcoma |

| Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma |

| Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma |

| Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma |

| So-called Fibrohistiocytic Tumors |

| Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma/malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) (including pleomorphic, giant cell, myxoid high-grade myxofibrosarcoma, and inflammatory forms) |

| Tumors of Peripheral Nerves |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor |

| Vascular Tumors |

| Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma |

| Deep angiosarcoma |

| Chondro-osseous Tumors |

| Extraskeletal chondrosarcoma or osteosarcoma |

| Tumors of Uncertain Differentiation |

| Synovial sarcoma |

| Epithelioid sarcoma |

| Alveolar soft part sarcoma |

| Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue |

| Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma |

| PNET/extraskeletal Ewing’s tumor |

| Desmoplastic round cell tumor |

| Extrarenal rhabdoid tumor |

| Undifferentiated sarcoma |

MFH, malignant fibrous histiocytoma; PNET, primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

From Fletcher C, Unni KK, Mertens F. Pathology and Genetics of Soft Tissue and Bone: World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002.

Liposarcomas are tumors composed of fat cells. The most common form that arises in the retroperitoneum is well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDLPS). Morphologically, it is similar to a typical lipoma; histologically, the presence of lipoblasts allows its recognition. WDLPSs show slow but progressive growth over many years without development of any metastasis. In approximately 25% of the cases, there is transformation into a higher grade of tumor. When dedifferentiation occurs, there is loss of mature fat, and the tumor grows faster and has the capacity to metastasize. These areas of dedifferentiated liposarcomas (DDLPSs) always occur in preexisting WDLPS and show an abrupt transition to a nonfat component. Sometimes, these areas that show dedifferentiation may display features of leiomyosaroma or other sarcoma on histology and by immune markers. Dedifferentiation is characterized by more aggressive local growth, a greater risk of recurrence after resection, and development of distant metastases in 15% to 30%. The myxoid/round cell and pleomorphic subtypes of liposarcomas are uncommon in the retroperitoneum.11

The common STSs in children are age-dependent. Up to age 14, rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common tumor type, whereas nonrhabdomyosarcomas are common in adolescents and young adults.10,12 In a single institutional report covering 30 years that specifically looked at retroperitoneal site of tumor origin, rhabdomyosarcoma, followed by fibrosarcoma, were reported as common types of RPSs in the pediatric age group.9 This pattern is distinctly different from common tumor histology in adults. The common subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma is embryonal arising in the genitourinary system. These tumors are large, infiltrative, and liable to involve adjacent organs at the time of initial presentation. Thus, positive margins may be present after gross resection of tumor. Microscopically, these tumor cells do not arise from skeletal myoblasts but rather resemble them.11

Clinical Presentation

RPSs lack specific symptoms or laboratory findings. They usually progress to a very large size before prompting the astute clinician to consider this diagnosis. A tip off can be a patient who is discovered to have a painless abdominal mass. Other presenting symptoms may be abdominal distention, back pain or pain referred to the hip, urine retention, hematuria, early satiety, GI obstruction, or weight loss, occurring singly or in combination. Neurologic deficits may be a presenting symptom when there is spinal cord, nerve root, or sciatic plexus involvement. Venous compromise can result in lower extremity edema. Although there is a broad age range, the sixth decade is a common time for presentation in adults. There is slight male predominance. Imaging, typically abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT), leads to discovery of the tumor. Eleven percent of patients with RPS at presentation have metastases to liver or lungs.14,15 Two thirds of the tumors are high grade at the time of diagnosis.14,15 Therefore, at their initial presentation, RPSs are at a higher stage and, consequently, their prognosis is worse than for extremity sarcomas.

Staging Evaluation

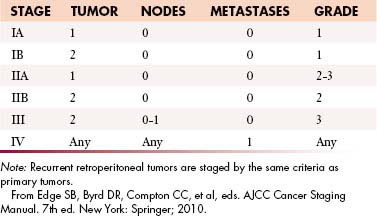

The current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for STS is based on a combination of anatomic as well as pathologic data: (1) tumor size, (2) depth, (3) histologic type, and (4) grade16 (Table 23-2). It has been derived from experience based on sarcomas of the extremities and applied to all sites including the retroperitoneum. The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) characteristics of the tumor are provided by imaging and may be modified after surgery. The histologic subtype and grade of the primary tumor are determined after biopsy or surgical excision to yield the stage of tumor by AJCC criteria.

Pathologic Criteria: Grading

1. Histology-specific differentiation: high, intermediate, or low grade. Also certain histologic types (synovial sarcoma, undifferentiated sarcoma, and sarcomas of unknown type) are always assigned a high score,

This combination of T, N, M, and G for AJCC staging is depicted in Figure 23-3.

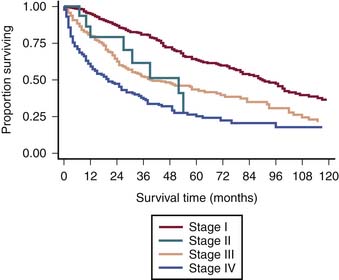

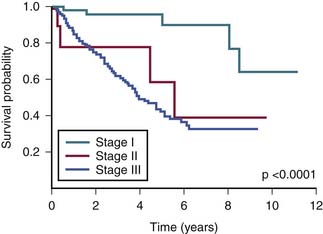

The survival graph shows better survival at lower stages (Figure 23-4). However, the absence of a major difference in survival between stage II (N0 disease) and stage III (N1 disease) points to a limitation in the current AJCC staging for RPSs (Figure 23-5).

Limitations of American Joint Committee on Cancer Classification

Site of Origin

The AJCC classification system does not differentiate retroperitoneal origin from extremity or other sites of origin. However, this does affect the stage at presentation and subsequent outcome.19 Therefore, when outcome data are being evaluated, it is important to consider RPSs as distinct from extremity, head and neck, gynecologic, and other sites of origin.

Size of Primary Tumor

The limitation of using an arbitrary 5 cm as the cutoff has been shown for retroperitoneal tumors that tend to be very often large at presentation. It is recognized that tumor size represents a continuous variable: the greater the size at initial presentation, the worse the outcome.19

Other Staging Systems

The most important common variables in the AJCC system for RPSs are the presence of distant metastasis M1 and the tumor grade G1-3. Therefore, alternate staging systems based only on tumor grade or with additional criteria of multifocality and the degree of residual tumor left after surgery (R0, R1, or R2) have been proposed and are as good as or even better than AJCC.17,18

Today, we are poised at the brink of important change with the availability of high-throughput technology of genomic, proteomic, and tissue microarray analysis in sarcoma. As the data about relevant genes and molecular markers are integrated with disease progression, tumor response, and survival, future modifications can be made to AJCC staging.

Patterns of Tumor Spread

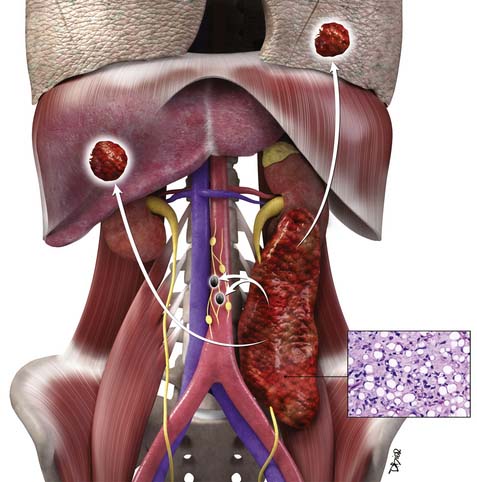

Hematogenous, Lymphatic, and Peritoneal Spread

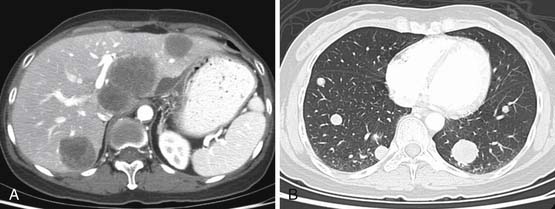

RPSs primarily spread to the liver via the hematogenous route. Such a pattern is seen in 44% of patients.14 Liver metastases, particularly from leiomyosarcoma and angiosarcoma, can have marked enhancement; hence, both pre- and postintravenous contrast CT of the liver should be performed as a routine in these patients. As the disease spreads further through the bloodstream, metastases can involve lungs in 38%, with additional sites of involvement of adrenals, muscles, subcutaneous tissue, bones, and brain.

Lymph node metastases are distinctly uncommon, occurring in only 3.5% of patients with STS.23 Lymph node involvement is more likely in patients with rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial, vascular, and epithelioid sarcoma.

Imaging

Primary Tumor Detection and Characterization

Radiologic considerations are critical in the successful management of RPS. The important imaging features to report are size, internal attenuation characteristics (fat, soft tissue, or calcification), enhancement or necrosis, relationship to adjacent organs (displacement or invasion), the spread of disease to distant organs, and the response to treatment when follow-up CT is performed. These are important considerations for the surgeon, who is concerned about anatomic constraints to complete resection. The key imaging characteristics of the common RPS are presented next.

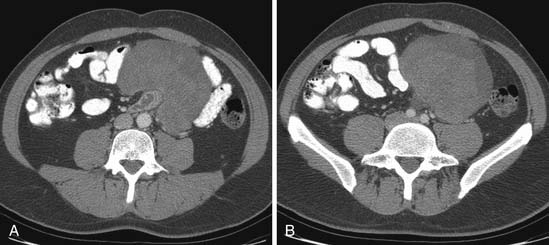

Liposarcoma

Liposarcoma is the most common RPS. Its typical appearance on CT is a bulky tumor with fat attenuation. It is recognized from generalized excess fat deposition seen with obesity by the mass effect that results in displacement of bowel loops or adjacent solid viscera. They may contain a few septations (Figure 23-7). These tumors are regarded as atypical lipomatous tumor (ALT) or WDLPS. When the attenuation of any area of tumor is greater than that of normal fat, has the attenuation of soft tissue density, or if contrast enhancement is seen, it must be reported as an area consistent with dedifferentiation (Figures 23-8 and 23-9). Such areas must be targeted for subsequent biopsy or surgery because DDLPS can be seen in as many as 15% of ALT/WDLSs.18 Whereas ALT/WDLPSs lack metastatic capacity, the DDLPS do disseminate and, consequently, have a particularly ominous prognosis.24

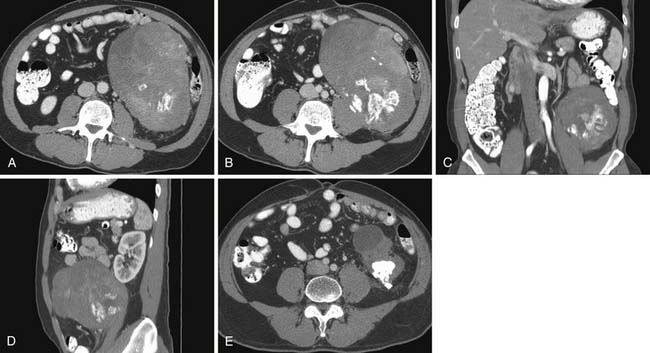

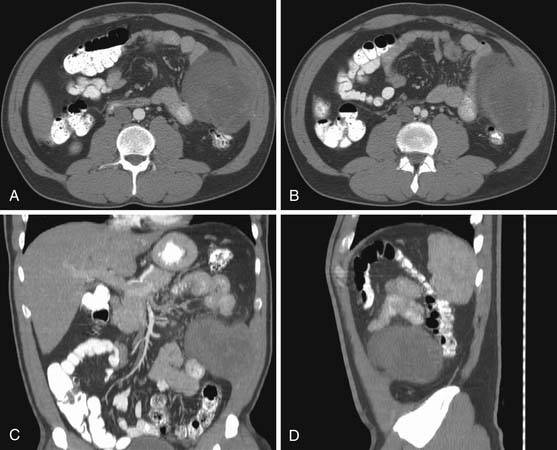

Leiomyosarcoma

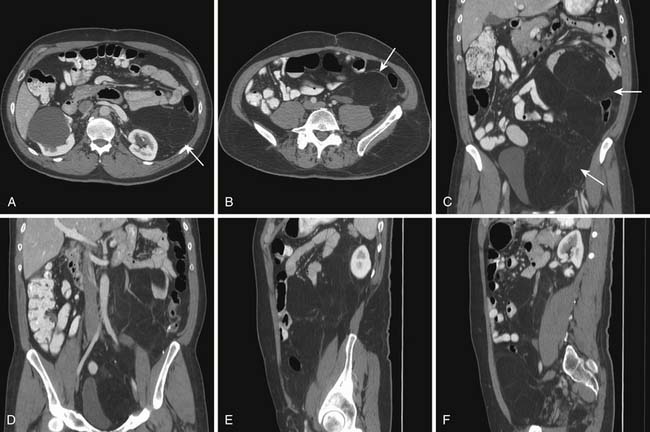

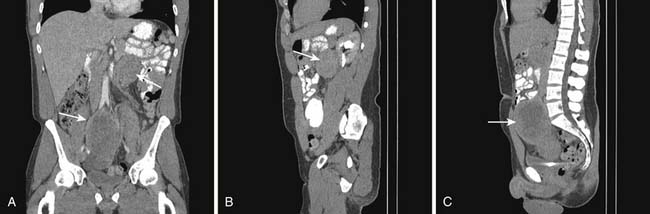

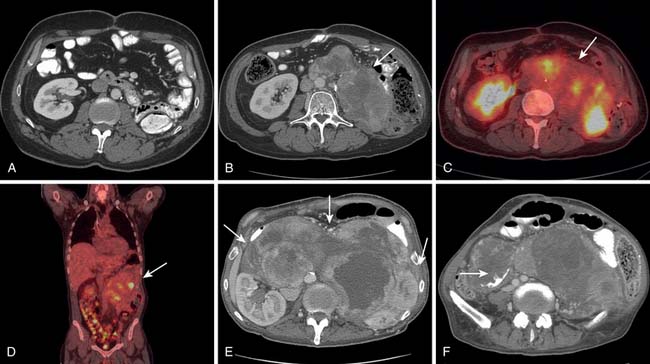

A leiomyosarcoma is the second most common histologic type of RPS. It has a typical CT appearance as a large mass with a central necrotic core. This is due to the rapidity with which it can proliferate and outgrow its blood supply. A subset of leiomyosarcoma arises from the inferior vena cava and commonly produces venous occlusion (Figures 23-10 and 23-11). Leiomyosarcoma, high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma (formerly called “malignant fibrous histiocytoma [MFH]”), and synovial sarcoma are infiltrative tumors (Figure 23-12). Thus, invasion of adjacent organs and the development of distant metastases are seen much more frequently with these tumors than with liposarcomas (Figures 23-13 and 23-14).

Figure 23-13 High-grade pleomorphic sarcoma of the retroperitoneum shows local invasion of the psoas and left paraspinal muscles.

Sarcomas Related to Genetic Syndromes

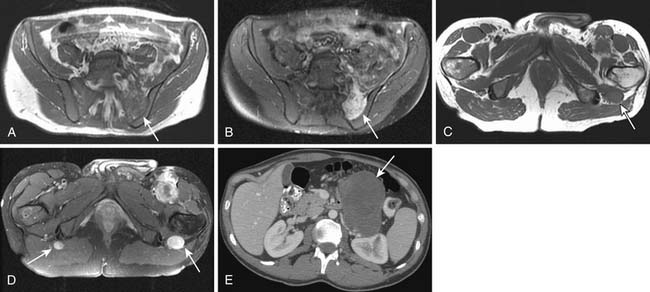

The manifestations of underlying genetic syndrome can be a tip off for related sarcomas. Desmoid tumors, typically in the root of the mesentery, can be multiple and are seen as a component of Gardner’s syndrome. In a patient with neurofibromatosis-1, any tumor associated with pain or enlargement of a plexiform neurofibroma must be assumed to represent malignant transformation and confirmed with a biopsy (Figures 23-15 and 23-16).

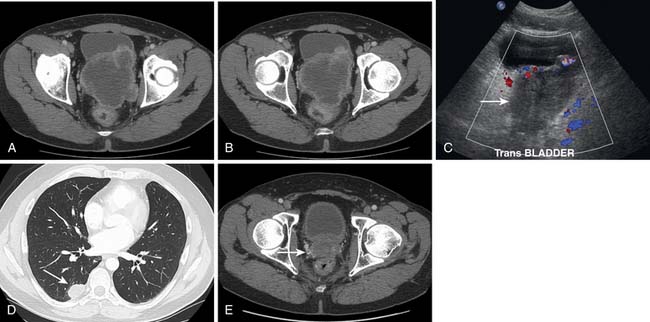

Pediatric Sarcomas

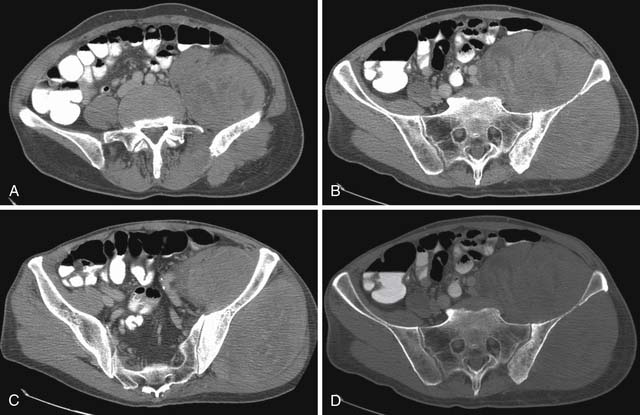

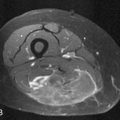

The most common RPS in children is rhabdomyosarcoma.9 It frequently arises from the genitourinary tract. These tumors are large, infiltrative, and liable to involve adjacent organs at the time of initial presentation (Figure 23-17). Nonrhabdomyosarcomas in pediatric age patients can be desmoplastic small round cell tumors (Figures 23-18 and 23-19), Ewing’s sarcomas (Figure 23-20), fibrosarcomas, and liposarcomas among others.

Lymph Node Metastases (N)

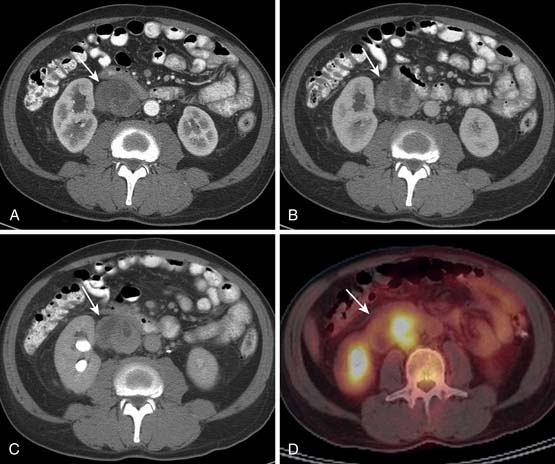

Although metastatic involvement of lymph nodes is defined as stage III disease in the most recent edition of the AJCC scheme, it is distinctly an uncommon occurrence.16 It is estimated to occur in 3.5% of all STSs in adults and slightly more commonly in children. When CT detects and characterizes RPS, attention should be directed to the regional lymph node drainage. The enlargement or any abnormal enhancement pattern must be included in the imaging findings. MRI can detect adenopathy using size, abnormal signal characteristics, and enhancement with gadolinium contrast as criteria for involvement. Metastatic adenopathy is characterized on positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT studies as fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG)-avid areas that correspond to lymph nodes anatomically.

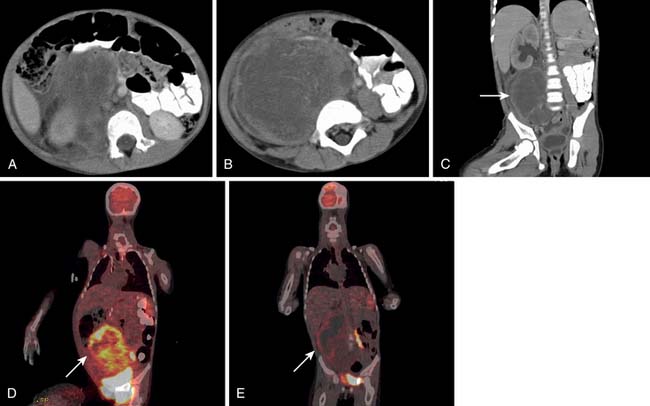

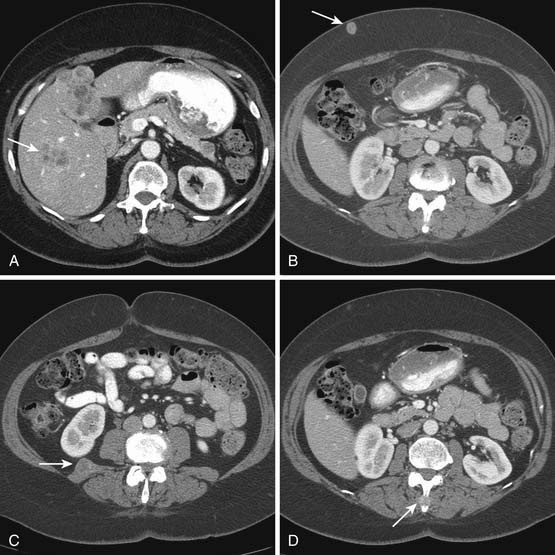

Distant Metastases (M)

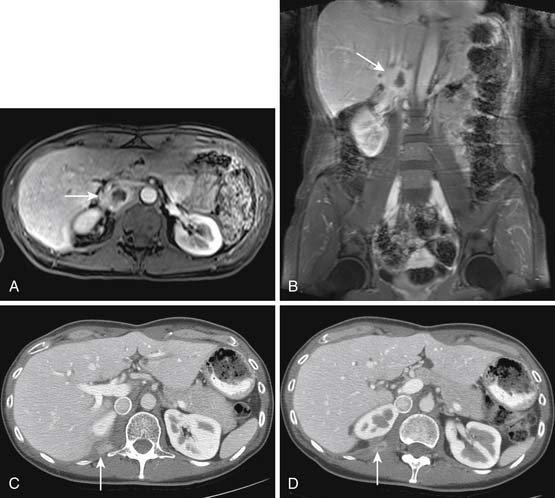

When CT is initially employed for the detection and characterization of RPSs, simultaneously an evaluation is made of the liver, which is a common site for hematogenous metastases (Figure 23-21). Other sites of metastases (i.e., adrenals, peritoneum, bones, and intramuscular or subcutaneous sites) are also assessed at the same time (Figures 23-22 and 23-23). This is especially important when CT demonstrates tumors other than ALT/WDLPS. A CT of the chest is very helpful for the detection of any metastasis to the lungs. MRI is necessary in the assessment of the brain and spine, especially when the patient has neurologic symptoms or impending cord compression (Figure 23-24). FDG-PET/CT will accumulate in distant sites of high-grade tumors, but these should be differentiated from areas of physiologic uptake or sites of infection. A nuclear medicine bone scan is useful in detection of bony metastases.

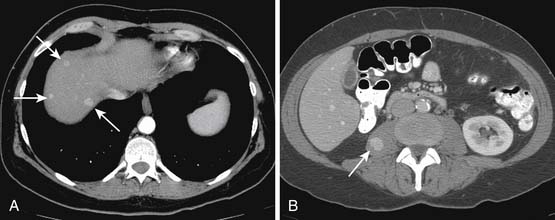

Figure 23-23 A and B, Enhancing sarcoma metastases (arrows) involve the liver and right psoas muscle.

After the initial CT, it is possible to provide a clinical (TNM) stage of disease. Then, for the pathologic aspects to complete staging, tissue diagnosis is necessary. If the tumor characteristics (small size or well-defined margins that displace adjacent structures) favor total surgical extirpation, surgery will serve as an excisional biopsy. When adjuvant therapy is a consideration (as in pediatric sarcomas), an imaging-guided biopsy is performed next. CT can guide the targeting of solid, non-necrotic portions of the tumor for biopsy. Although fine-needle biopsy can yield material for the diagnosis of malignancy, a core biopsy is preferred for the greater amount of tissue it provides. This allows determination of tumor grade based on the criteria of cellular differentiation and necrosis to be made for a comprehensive AJCC staging. In the event of a negative biopsy, an open biopsy should be pursued.25 With the imaging detection of metastases, a core biopsy can be obtained from either the primary tumor or the metastatic site as appropriate.

Therapy

Surgical Therapy

Complete resection is much more difficult to achieve in infiltrating lesions versus the more indolent pushing type of sarcoma, which usually abut but do not invade critical structures that are in immediate proximity to the tumor. Major arterial and venous reconstruction can be undertaken with the simultaneous resection of GI tract and multiple organs during en bloc surgery for RPSs26,27 (Figure 23-25). When comparing the current practice of aggressive surgery with the higher incidence of multiple organ resection with the earlier surgical experience, a study found improvement in the rate of complete resection (78% vs. 49%) and overall survival (58% vs. 39%). However, local recurrence continues to be a significant problem.28 Because new surgical options are limited, this calls for adjuvant therapy for further improvement in outcome.

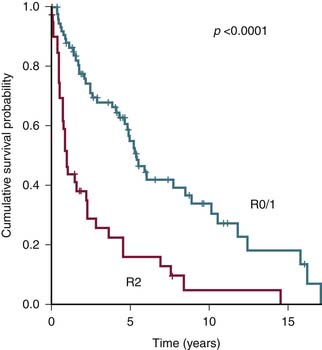

Contraindications to resection must be individualized; however, long segment superior mesenteric vein encasement is particularly worrisome because of the high likelihood of venous compromise after resection. Although R0 resection is the goal, it may not be possible owing to tumor size or its location. R1 resection, for primary and recurrent lesions, particularly in well-differentiated, low-grade liposarcomas, may create a meaningful span of freedom from disease. It may, therefore, be quite favorable for the individual patient.29,30 Unfortunately, recurrence occurs eventually in the vast majority (Figure 23-26).

Radiation Therapy

Whereas surgical resection is the mainstay of management for RPSs, radiation therapy is sometimes employed for primary local management in an effort to improve local control of these tumors.31 The decision to use radiation therapy as an adjuvant to surgical management can hinge on many factors, and it should be undertaken in a multidisciplinary team setting. The diagnostic imaging and its interpretation are critical to the decision-making process and in planning delivery of radiation treatment. Current practice patterns have evolved such that, in the preoperative setting, a lower total dose is preferred over radiation therapy administered postoperatively.7 Even so, the recommended total dose of 45 to 50.4 Gy given preoperatively exceeds the normal tissue tolerance for many of the critical structures that are often in proximity to these tumors. CT is the preferred imaging modality for radiotherapy management decisions as well as treatment planning.

An appreciation on imaging studies of the size and extent of RPS is important to decide the feasibility and technique for radiation therapy. Also, it is important to assess multifocality of tumor deposits because such patients may not be suitable candidates to receive radiation therapy. The amount of small bowel approximating the tumor is critical because a proposed therapy field that would include a large volume of small bowel will be a contraindication to the use of radiation therapy. For right-sided retroperitoneal tumors, the proximity to liver is of importance because significant volumes (>30%) of the liver tissue cannot be irradiated to the prescribed dose without risk of unacceptable toxicity.32 If a large volume of liver must be irradiated to cover the area at risk, radiotherapy may not be advisable in such cases. The proximity of the kidneys is important to assess whether radiation therapy is feasible. If one kidney may be rendered nonfunctional by radiation therapy, a renal scan is advisable to ascertain the function of the contralateral kidney to ensure that adequate renal function will remain after radiation therapy. In children, consideration should be given to the proximity to any growth plates that could result in subsequent bone deformity.

The premature closure of a prospective trial to evaluate surgery alone versus preoperative radiotherapy and surgery for lack of accrual is symptomatic of the inherent problems in the study of RPS: low incidence of disease and negative perception about randomization to adjuvant therapy.33 Intraoperative radiotherapy, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), and proton therapy hold promise and deserve to be evaluated on a rigorous basis in the future with the goal of maximum benefit and minimum toxicity customized to the individual patient.

Chemotherapy

It is imperative that a multidisciplinary review of the clinical information at a specialized center precede implementation of chemotherapy. Tumors that are small or low grade are unlikely to metastasize and are, therefore, well managed with surgery with or without radiation therapy. Large or high-grade tumors have a greater propensity for metastases and need to be discussed in a multidisciplinary conference to determine the appropriateness of systemic therapy and the most beneficial sequence (preoperative vs. postoperative), acknowledging that the standard of care is complete surgical resection.34 Systemic therapy remains the palliative standard of care for patients who have metastatic disease. Surgical consolidation may be appropriate for a select minority of these patients who can be resected completely and rendered free of all gross disease.

Key Points Therapy considerations

• Surgery provides the most definitive treatment for RPSs.

• Radiation therapy is used at specialized centers selectively in a preoperative setting to reduce local recurrence.

• Chemotherapy may be used in large or high-grade tumors in either preoperative or postoperative setting and as palliation for metastatic disease.

Key Points What the surgeon, the radiation oncologist, and the medical oncologist want to know

• Surgeon: Tumor size, presence of fat, displacement or invasion of organs, multifocality, and vascular involvement to plan resection.

• Radiation oncologist: Size and relationship of tumor to radiosensitive organs to plan radiation therapy field.

• Medical oncologist: Tumor size, metastases, and measurement of response to chemotherapy on follow-up imaging.

Surveillance

Monitoring Tumor Response

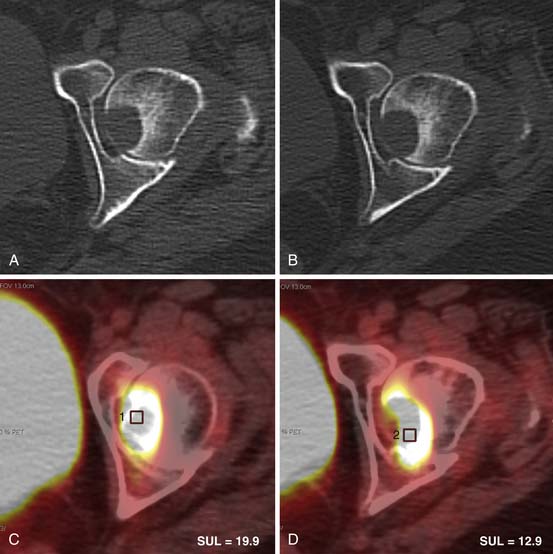

Radiation or chemotherapy may be directed at preoperative tumor reduction so that subsequent surgery will provide tumor-free (R0) resection margins. Alternatively, such therapy may be given after surgery when there is microscopic (R1) or gross residual disease (R2) for local control. In addition, conventional chemotherapy is used for palliation in the patient with distant metastatic disease (M1). It is important to be able to evaluate tumor response in all these settings. Reduction in the size of tumor and target lesions using Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) has been used as a sign of response historically. However, such response does not necessarily lead to increased survival. Recent experience in the treatment of GISTs has shown the utility of tumor metabolism as an indicator of tumor response when evaluated with PET. A change in tumor attenuation but not tumor size by CT is a consequence of such targeted therapy.35 PET is valuable in assessment of early tumor response in high-grade RPSs.36 Whereas different parameters of glucose kinetics have been suggested, the standard uptake value (SUV) is utilized most commonly in everyday practice.37 FDG-PET may also prove very useful when novel targeted therapy is being investigated because reduction in SUV can provide an early separation of responders from nonresponders. Newer radiotracers such as thymidine analogue 3’-deoxy-3’ 18F fluorothymidine appear promising for even better means of evaluating tumor metabolism.38 Tumor volume reduction and tumor necrosis as indicators of tumor response may be evaluated with MRI and deserve to be evaluated rigorously.

Detection of Recurrence

The risk of local recurrence is the highest early after surgery, with two thirds occurring within 2 years.6 The overall local recurrence rate in RPS ranges from 40% to 90%. Recurrence in the abdomen is common, with metastases to liver being frequent, followed by lung metastases. It is, therefore, recommended that, in patients with high-grade tumors, CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis be performed at 3- to 4-month intervals for 3 years, subsequently at 6-month intervals for 2 years, and then annually. For low-grade tumors, the recommendation is to undergo CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis at 3- to 6-month intervals for 2 to 3 years and then annually. Such surveillance frequency is widely used in clinical practice, but its benefit has not been proved in a prospective trial.25 The 5-year survival rate in RPS is from 40% to 52%, and it drops to 28% if there is local recurrence.39,40 The duration of surveillance should continue beyond the conventional timeframe because recurrence and metastases in RPS do occur beyond 5 years.

While local recurrence occurs 40% to 90% in RPS, the recurrence rate in extremity sarcoma is only about 10%. The resection of recurrent tumor in the retroperitoneum has been shown to provide prolonged local control, and it can be undertaken multiple times, especially in patients with low-grade well-differentiated liposarcoma, However, whereas primary resection results in complete resection in 80% of patients, with recurrence, complete resection is achieved in 57%, and it gets less with subsequent recurrence.14,15

There remain many unanswered questions in the management of the patient with metastatic sarcoma. What is the place of metastatectomy of liver or lung lesions? What is the optimal combination and sequence for chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery? Such topics can best be addressed definitively in large, multiple-institution clinical trials. Until then, multi-institutional cooperative groups can work to provide the best possible data for the care of the patient with RPS to improve quality of life and prolong survival.

Key Points Detecting recurrence

• Surveillance with CT of chest, abdomen, and pelvis is performed more frequently with high-grade tumor and continued annually beyond 5 years.

• Recurrence commonly occurs within the abdomen at the resection site, followed by metastases to liver and lung.

• Complete resection of recurrent tumor is less successful with each subsequent surgery.

Complications of Therapy

Surgical Therapy

The overall complication rate is 5% to 10%.41 Complications are usually in the early postoperative period and, when severe, can include bleeding, myocardial infarction, or sepsis. Wound dehiscence, abscess, anastomotic leak, or bowel obstruction may also occur.42

Radiation Therapy

Acute GI toxicity may occur when small bowel loops are in the irradiated field. In severe cases, dehydration may necessitate treatment with intravenous fluids. With brachytherapy, duodenitis, stricture formation, and perforation, especially if nasojejunal intubation is performed, may occur. If preoperative radiotherapy is given, delayed wound healing may be seen. Any portion of the kidney in the radiation field will lose function, so adequate reserve of renal function should be ensured before radiation therapy. Stricture and bowel obstruction can be seen as late complications.42,43 In a child, if any growth plate is included in the radiation portal, impaired growth and bony deformity may occur later. A slightly higher risk of radiation-induced second tumor is possible. However, the benefit of radiation therapy far outweighs this relatively small risk and it must not be withheld when indicated.

Chemotherapy

Key Points Complications of therapy

• Surgical complications may be early (hemorrhage, infection, or anastomotic leak) or late (bowel obstruction).

• Complications from radiation therapy involving organs in the treatment field include enteritis, bowel stricture, organ atrophy, and slightly higher risk of induced tumor.

• Chemotherapy commonly results in nausea and vomiting; myelosuppression may predispose to infection; cardiac, renal, and neurotoxicity can occur.

New Therapies

The development of optimal treatment strategies for sarcoma has been greatly complicated by the large number of subtypes, the heterogeneity in their biologic behavior, and the small number of patients with particular subtypes enrolled in trials. Lessons learned from the exciting experience of targeted therapy with imatinib in GISTs have encouraged basic and translational research in different subsets with limited success.44 Potential new targets relevant to sarcomas originating in the retroperitoneum are CDK-4 and MDM2 in WDLPSs/DDLPSs; mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, PEComas, and lymphangioleiomyomatosis; and ALK 1 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. These will need to be studied and validated in the clinic with appropriate inhibitors. It is essential that clinical trials archive pretreatment biopsy material to allow molecular analysis for later studies. Continued attempts at finding the relevant target and its well-tolerated inhibitor are likely to improve outcomes in this rare group of diseases.

Conclusion

RPSs present a challenge in management because of their heterogeneity, location, local invasion, and propensity for local recurrence. Surgical therapy offers the best hope for cure; however, even with aggressive resection, local recurrence occurs frequently. For patients with high-grade RPSs, distant metastases also contribute to mortality. Optimal disease control with surgery and adjuvant therapy with minimal morbidity is the desired goal of therapy. Large, randomized, controlled trials to address the most effective adjuvant therapy are essential to provide evidence-based treatment for the patient with RPS.45

1. Jemal A., Siegel R., Ward E., et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225-249.

2. Porter G.A., Baxter N.N., Pisters P.W. Retroperitoneal sarcoma: a population-based analysis of epidemiology, surgery, and radiotherapy. Cancer. 2006;106:1610-1616.

3. Patel S.R. Radiation-induced sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2000;1:258-261.

4. Brady M.S., Gaynor J.J., Brennan M.F. Radiation-associated sarcoma of bone and soft tissue. Arch Surg. 1992;127:1379-1385.

5. Amendola B.E., Amendola M.A., McClatchey K.D., Miller C.H.Jr. Radiation-associated sarcoma: a review of 23 patients with postradiation sarcoma over a 50-year period. Am J Clin Oncol. 1989;12:411-415.

6. Clark M.A., Fisher C., Judson I., Thomas J.M. Soft-tissue sarcomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:701-711.

7. Thomas D.M., O’Sullivan B., Gronchi A. Current concepts and future perspectives in retroperitoneal soft-tissue sarcoma management. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1145-1157.

8. Matushansky I., Charytonowicz E., Mills J., et al. MFH classification: differentiating undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma in the 21st century. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1135-1144.

9. Pham T.H., Iqbal C.W., Zarroug A.E., et al. Retroperitoneal sarcomas in children: outcomes from an institution. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:829-833.

10. Herzog C.E. Overview of sarcomas in the adolescent and young adult population. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:215-218.

11. Wu J.M., Montgomery E. Classification and pathology. Surg Clin North Am.. 2008;88:483-520. v-vi

12. Loeb D.M., Thornton K., Shokek O. Pediatric soft tissue sarcomas. Surg Clin North Am.. 2008;88:615-627. vii

13. Fletcher C., Unni K.K., Mertens F. Pathology and Genetics of Soft Tissue and Bone: World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002.

14. Lewis J.J., Leung D., Woodruff J.M., Brennan M.F. Retroperitoneal soft-tissue sarcoma: analysis of 500 patients treated and followed at a single institution. Ann Surg. 1998;228:355-365.

15. Hueman M.T., Herman J.M., Ahuja N. Management of retroperitoneal sarcomas. Surg Clin North Am.. 2008;88:583-597. vii

16. Edge S.B., Byrd D.R., Compton C.C., et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th ed, New York: Springer, 2010.

17. Nathan H., Raut C.P., Thornton K., et al. Predictors of survival after resection of retroperitoneal sarcoma: a population-based analysis and critical appraisal of the AJCC staging system. Ann Surg. 2009;250:970-976.

18. Anaya D.A., Lahat G., Wang X., et al. Establishing prognosis in retroperitoneal sarcoma: a new histology-based paradigm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:667-675.

19. Kotilingam D., Lev D.C., Lazar A.J., Pollock R.E. Staging soft tissue sarcoma: evolution and change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:282-291. quiz 314–315

20. Stojadinovic A., Leung D.H., Hoos A., et al. Analysis of the prognostic significance of microscopic margins in 2,084 localized primary adult soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Surg. 2002;235:424-434.

21. Zagars G.K., Ballo M.T., Pisters P.W., et al. Prognostic factors for patients with localized soft-tissue sarcoma treated with conservation surgery and radiation therapy: an analysis of 1225 patients. Cancer. 2003;97:2530-2543.

22. Alldinger I., Yang Q., Pilarsky C., et al. Retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas: prognosis and treatment of primary and recurrent disease in 117 patients. Anticancer Res.. 2006;26:1577-1581.

23. Fong Y., Coit D.G., Woodruff J.M., Brennan M.F. Lymph node metastasis from soft tissue sarcoma in adults. Analysis of data from a prospective database of 1772 sarcoma patients. Ann Surg. 1993;217:72-77.

24. Anaya D.A., Lahat G., Liu J., et al. Multifocality in retroperitoneal sarcoma: a prognostic factor critical to surgical decision-making. Ann Surg. 2009;249:137-142.

25. Windham T.C., Pisters P.W. Retroperitoneal sarcomas. Cancer Control. 2005;12:36-43.

26. Schwarzbach M.H., Hormann Y., Hinz U., et al. Clinical results of surgery for retroperitoneal sarcoma with major blood vessel involvement. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:46-55.

27. Song T.K., Harris E.J.Jr., Raghavan S., Norton J.A. Major blood vessel reconstruction during sarcoma surgery. Arch Surg. 2009;144:817-822.

28. Hassan I., Park S.Z., Donohue J.H., et al. Operative management of primary retroperitoneal sarcomas: a reappraisal of an institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2004;239:244-250.

29. Anaya D.A., Lev D.C., Pollock R.E. The role of surgical margin status in retroperitoneal sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:607-610.

30. Anaya D.A., Lahat G., Wang X., et al. Postoperative nomogram for survival of patients with retroperitoneal sarcoma treated with curative intent. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:397-402.

31. Pawlik T.M., Pisters P.W., Mikula L., et al. Long-term results of two prospective trials of preoperative external beam radiotherapy for localized intermediate- or high-grade retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:508-517.

32. Emami B., Lyman J., Brown A., et al. Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.. 1991;21:109-122.

33. Kane J.M.3rd. At the crossroads for retroperitoneal sarcomas: the future of clinical trials for this “orphan disease.”. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:442-443.

34. Schuetze S.M., Patel S. Should patients with high-risk soft tissue sarcoma receive adjuvant chemotherapy? Oncologist. 2009;14:1003-1012.

35. Choi H. Response evaluation of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Oncologist. 2008;13:4-7.

36. Schwarzbach M.H., Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A., Willeke F., et al. Clinical value of [18-F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Surg. 2000;231:380-386.

37. Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A., Strauss L.G., Egerer G., et al. Impact of dynamic 18F-FDG PET on the early prediction of therapy outcome in patients with high-risk soft-tissue sarcomas after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a feasibility study. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:551-558.

38. Schmitt T., Kasper B. New medical treatment options and strategies to assess clinical outcome in soft-tissue sarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1159-1167.

39. Billingsley K.G., Burt M.E., Jara E., et al. Pulmonary metastases from soft tissue sarcoma: analysis of patterns of diseases and postmetastasis survival. Ann Surg. 1999;229:602-610. discussion 610–612

40. Eilber F.C., Eilber K.S., Eilber F.R. Retroperitoneal sarcomas. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2000;1:274-278.

41. Singer S., Eberlein T.J. Surgical management of soft-tissue sarcoma. Adv Surg. 1997;31:395-420.

42. Mendenhall W.M., Zlotecki R.A., Hochwald S.N., et al. Retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2005;104:669-675.

43. Caudle A.S., Tepper J.E., Calvo B.F., et al. Complications associated with neoadjuvant radiotherapy in the multidisciplinary treatment of retroperitoneal sarcomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:577-582.

44. Patel S., Zalcberg J.R. Optimizing the dose of imatinib for treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumours: lessons from the phase 3 trials. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:501-509.

45. Katz M.H., Choi E.A., Pollock R.E. Current concepts in multimodality therapy for retroperitoneal sarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:159-168.