CHAPTER 27 Primary and Secondary Mastopexy-Augmentation

Summary/Key Points

Introduction

The idea of treating hypoplastic and ptotic breasts with a combined implant and lift was first described in the 1960s by Gonzalez-Ulloa and Regnault.1,2 Since then, there has been much written on the subject, both in support of the procedure and in cautioning about the potential risks and possible adverse outcomes.

Cardenas-Camarena published his experience with 384 patients undergoing one stage mastopexy-augmentation.3 His complication rate of 18%, all described as minor, was very favorable. His approach was to first insert the implant and then plan the skin excision around the newly implanted breast. He provided guidelines for the pattern of skin excision based primarily on the degree of ptosis of the nipple–areola complex (NAC) and on the distance from the NAC to the inframammary fold (IMF).

In 2007 Stevens reported on 321 consecutive one stage mastopexy-augmentations.4 Approximately two-thirds of these were primary procedures and one-third were in patients with previous breast augmentation or previous breast lifts. Complications over an average 40 month follow up were rare and included saline implant deflation, poor scarring, recurrent ptosis and areola asymmetry. The total revision rate was 14.6% with three-quarters of these being implant related and one-quarter being tissue related. He compared these results favorably to a 13% revision rate in his breast implant only patients and an 8.6% revision rate in his mastopexy only patients. Stevens noted that revision was most common in smokers, those undergoing a circumareolar lift and patients having augmentation with saline implants. He concluded with the statement that ‘although a revision rate of 14.6% is significant, it is far from the 100% reoperation rate required for a staged procedure.’4

Spear has written about his experience with combined breast augmentation and breast lift and cautions about the increased risks and revisions associated with this approach.5 He noted a 10-fold increase in complications when comparing primary augmentation mastopexy with primary augmentation only. As a guideline, he recommended that women undergoing breast augmentation could avoid a simultaneous mastopexy if the nipple sits at or above the IMF, if the nipple and areola are visible on the front of the breast with some inferior non-areola skin being visible, if the breast overhangs the IMF by no more than 2 cm and if the nipple to IMF distance is less than or equal to 8 cm under maximum stretch.

It is important to differentiate between primary one stage augmentation mastopexy and secondary procedures that are performed following a previous implant or lift. Handel’s paper titled ‘Secondary mastopexy in the augmented patient: a recipe for disaster’,6 highlights some of the key issues that must be considered in this complex patient population. Over time, augmented breasts, especially those placed in a subglandular plane, become ptotic and develop thinning of the overlying breast tissue. The majority of these soft tissue effects are seen in the lower pole of the breast. Often, there are associated contractures of the surrounding capsules. Correction of this deformity may require explantation only, mastopexy with explantation or mastopexy with or without implant exchange or pocket change7 (Figs 27.1 and 27.2).

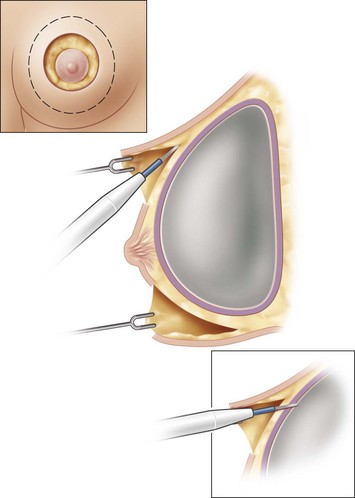

Handel makes several recommendations for dealing with these patients. Preoperative deflation of a saline implant allows the patient to see the breast in a deflated state and allows the surgeon to better assess the quality and quantity of remaining breast tissue. This simple step will provide valuable information that may affect the choice of operation selected by the patient. If a mastopexy is required, undermining should be minimized and capsulectomy should only be performed when necessary. It is important to make note of previous breast scars, especially as they relate to the vascular supply of the NAC. Since inferior pole tissues are often attenuated, use caution in selecting an inferior based pedicle. It may often be best to excise the thin lower pole tissues and select a superiorly based pedicle, where tissues are of better quality. Finally, in circumareolar incisions, especially with a subglandular implant, it is important to bevel the plane of dissection acutely due to the thin nature of the tissue between the skin and the underlying implant. Failure to recognize this may lead to vascular compromise of the nipple (Fig. 27.3).

Patient Selection

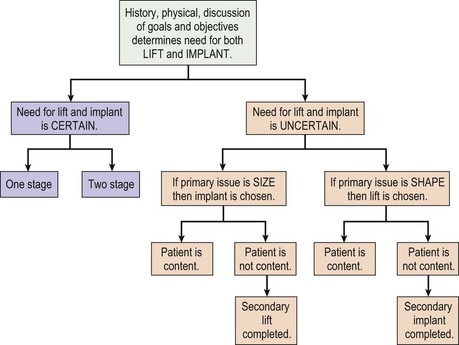

The fundamental decision that must be made between patient and surgeon is what is the best operation to most closely meet the patient’s goals and objectives of surgery. This may be a mastopexy, an augmentation or a combination of both. Although some patients can only be adequately treated with a combined procedure, every consideration should be made to addressing the patient’s concerns with a single procedure, if possible (Figs 27.4 and 27.5). Initially, the patient’s goals must be clearly reviewed. Are the concerns related to size, shape, symmetry, NAC position, areola size, stretch marks or some combination? Which of these is most important to correct and what is the patient prepared to trade off in order to obtain this correction? Essentially, a risk benefit analysis must be applied after a thorough discussion about options and complications. If a mastopexy and augmentation are to be performed together, a further decision of whether or not to perform the surgery in one stage or two stages is necessary. A one-stage approach should be reserved for healthy patients, non-smokers with few risk factors for impaired healing. These patients should be certain that they desire both a lift and an implant, otherwise the issue most important to the patient is treated first. Once healed, the patient can determine if they require the second procedure to satisfy their goals. A decision tree can be helpful in performing this analysis (Fig. 27.6).

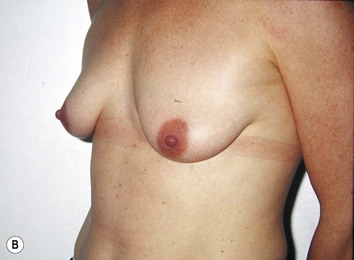

Fig. 27.5 A, B Preoperative views of patient with ptosis and good breast volume. C, D Six week postoperative views following vertical scar mastopexy using an inferior flap secured under a pectoralis sling.9

Physical examination focuses on overall body proportions and the relationship of breast size to the rest of the body. Breasts are examined for size, shape, symmetry, nipple position and stretch marks. Ptosis is assessed as defined by Regnault.8 It is important to assess the quality of the breast tissue and skin in all zones of the breast. This information is helpful in deciding whether tissue should be excised and if so, then from which zone. Standard measurements of sternal notch to nipple, nipple to IMF, breast width and nipple to midline are documented. Finally, a breast examination is performed for abnormal masses.

Indications

Operative Technique (Table 27.1)

Markings

Table 27.1 Summary of operative steps for primary mastopexy-augmentation

Once the height of the NAC is determined, the remainder of the markings are dependent upon the planned skin pattern of excision. Whether marking out a crescent lift, a circumareolar excision, a vertical skin pattern or a Wise pattern excision, markings should be very conservative with the expectation that more skin will be excised at the time of tailor tacking (Fig. 27.7).

Technique

Options for the plane of dissection include subglandular, subfascial, subpectoral, or dual plane. Subpectoral or subfascial pockets have the potential for providing some stability and support to the implant which may result in less stretching of the overlying tissues with time. A subpectoral location is necessary when there is inadequate breast tissue to cover the implant, especially in the upper pole. Although placing the implant under the muscle maximizes soft tissue coverage, patients should be made aware that there are tradeoffs with this approach. As women age, the breast tissue will tend to become ptotic. With the implant under the muscle, it will be held in a superior position, rather than descending with the breast tissue. This ‘waterfall’ deformity will require further lifting of the breast for correction (Fig. 27.8).

Implant selection

There are many implant choices today for use in breast augmentation (Table 27.2). The advantages and disadvantages of each implant type are beyond the scope of this discussion but several points are worth noting. Saline filled implants have the benefit of acting as a sizer in that they can be progressively inflated to desired tension, allowing for flexibility in volume selection. Of course, adequate tissue coverage is necessary to minimize rippling and palpability of the device. Saline implants have a firmer feel than gel implants and are likely to produce a fuller look in the upper pole (Fig. 27.9). Stevens found that in his experience with one stage mastopexy-augmentation, 31% of the implants used were saline however they accounted for 49% of the revisions. These were primarily performed for deflation and rippling.4

There is a role for both round and shaped implants in combined augmentation with mastopexy. Shaped stable cohesive gel implants are an excellent choice in patients with a tight or constricted lower pole as seen in the tuberous breast deformity (Fig. 27.10). As well, the differential fill volume in the lower pole of the implant provides more lift of a slightly ptotic NAC than a round device. This is particularly useful in patients with postpartum ptosis and may allow the patient to either do without a lift or to have less of an aggressive lift (Fig. 27.11). In patients with looser skin envelopes, and especially when the selected implant diameter is narrower than the diameter of the breast, a round implant is preferred. Use of a shaped device in this situation may result in rotation or malposition of the implant due to inadequate soft tissue support.

Shaping the breast

Once it has been determined how much skin to remove, the patient is returned to a supine position and the tacking sutures are removed. The areola is incised with use of an appropriate diameter nipple marker and the skin within the pattern is de-epithelialized. Limited undermining of the skin flaps is carried out to minimize further vascular disruption to the NAC and to the skin flaps. Undermining is only carried as far as necessary to allow for closure with a comfortable degree of tension. In breasts where there is excess tissue in the lower pole, there may be benefit to excising some of the tissue. Otherwise, it may eventually become ptotic, and given the fact that the implant will provide adequate volume, the tissue becomes redundant. When performing a mastopexy only, repositioning the lower pole tissues as described by Graf and Biggs9 is an excellent alternative to excising the ptotic tissue. This approach is contraindicated in combined procedures as the blood supply to the inferior chest wall flap will have been disrupted during implant insertion.

Closure is carried out in two layers with multiple subdermal sutures followed by a running subcuticular stitch. An absorbable monofilament suture is used. In situations where there is excess tension on the areola, a permanent suture is used to control the areola diameter. This is most always necessary in circumareolar techniques. Ideally, the suture should be non-absorbable and glide easily when tightened. A variety of approaches to placing this suture have been described.10,11 The interlocking Gore-Tex approach published by Hammond is a very effective option that would appear to provide long term control.11 Examples of various mastopexy-augmentation approaches are illustrated in Figs 27.12–27.14.

The tuberous breast

In type 1, 2, and most type 3 tuberous breasts, a one stage approach is indicated.12 If there is areola hypertrophy or herniation, a circumareolar approach is selected. In cases where there is also ptosis with redundant skin in the lower pole, a circumvertical approach is used. Dissection is carried through the breast to the pectoral muscle. Ideally, a subglandular pocket is selected as this will provide the most direct stretch against the constricted breast tissues. In patients with minimal tissue in the upper pole, a dual plane pocket is used. Aggressive radial scoring is performed. Often, it is necessary to score through the breast to the level of the dermis. A shaped form stable cohesive gel implant is an ideal choice for this patient population.13 The implant provides an added degree of resistance to the tight lower pole tissues, assisting in both short term and long term shape. The shape of the device has greater lower pole projection which is ideal in patients with deficiency in this area. The tapered upper portion also provides a natural contour to the superior part of the breast. Tuberous breasts generally have a narrow base with minimal lateral tissue. The implant is used to assist in providing a wider base and more natural lateral contour. As a result, rippling and implant edge palpability is common. This is less likely to occur with a form stable device than it is with a softer gel or saline filled implant (Fig. 27.15).

Secondary mastopexy-augmentation

Perhaps the most common problem seen is a patient who has undergone previous subglandular breast augmentation. Often, the implants are large for both the size of the patient and the overlying soft tissue envelope. There is thinning of the breast tissue, ptosis of the NAC and often a contracture of the surrounding capsule (Fig. 27.16). Options for correction include explantation or explantation with mastopexy (Fig. 27.17). This latter option can only be considered if there is an adequate amount of tissue to create a breast with reasonable shape. In patients with saline implants, preoperative deflation in the office allows an assessment of breast volume and shape. This can be a very helpful and educational maneuver but requires that the patient be completely committed to a further operation. A third option involves implant exchange, either subglandular or in a new subpectoral pocket, along with a mastopexy. This is the option most commonly selected by the patient as it allows for correction of ptosis while maintaining breast size.

The decision as to what pocket to use is based upon tissue thickness. If there is adequate tissue when the breast is lifted up to the implant, then a subglandular space can be reused. This is the most straightforward approach. Otherwise, the implant should be placed in a new subpectoral pocket. In this situation, something must be done to keep the implant below the muscle. Options include closure of the subglandular space with sutures, marionette sutures from the edge of the pectoral muscle through the skin or the addition of an acellular dermal matrix from the pectoral muscle down to the IMF.7

A second common scenario is the patient who has previously undergone a breast reduction or a breast lift and has lost volume due to weight loss, pregnancy or breast feeding. There is deflation of the skin envelope and loss of projection. Often the sternal notch to nipple distance is normal but glandular ptosis or pseudoptosis exists (Fig. 27.18). When planning correction, it is important to note the location of previous scars, the quality of the skin and where the redundant skin is located. Previous operative reports that describe the pedicle used for nipple transfer are very helpful, if available.

Treatment includes restoring volume with the use of a breast implant and controlling the lower pole tissues. A round implant is usually selected as shaped devices will be prone to rotation and malposition in loose skin envelopes. Depending on the size of the implant selected and the degree of pseudoptosis, tightening of the lower pole may be necessary. If the nipple is in a normal position, an inverted T excision is performed without incising around the areola. If the nipple is felt to be too low, then a circumareolar component to the lift is included. When redundant lower pole breast tissue exists, consideration should be made for excision of this tissue along with the skin (Fig. 27.19). This essentially removes the tissue that would tend to become ptotic with time.

A final consideration is the patient with a subpectoral or submuscular implant and overlying mastopexy. With time, the implant may move superiorly and the breast tissue inferiorly resulting in a ‘waterfall’ deformity. If the patient has adequate tissue volume, the implant can be removed and a second mastopexy performed. Otherwise, treatment is carried out by repositioning a new implant into a neosubpectoral pocket and revising the mastopexy (Fig. 27.20). This pocket is created on top of the existing capsule and deep to the pectoral muscle. This allows the upper pole coverage to be maintained while letting the implant drop down to the planned IMF.

Pitfalls and How to Correct

The risks of performing a combined mastopexy-augmentation are greater than the sum of either operation performed on its own (Table 27.3). Careful planning, judicious patient selection, and precise surgical technique will assist in minimizing poor outcomes.

* Risk that is increased by combining surgical procedures.

Common pitfalls that affect the final result are listed below with recommendations for correction.

1 Gonzales-Ulloa M. Correction of hypotrophy of the breast by exogenous material. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1960;25:15.

2 Regnault P. The hypoplastic and ptotic breast. A combined operation with prosthetic augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;37:31.

3 Cardenas-Camarena L, Ramirez-Macias R. Augmentation/mastopexy: how to select and perform the proper technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30:21-33.

4 Stevens WG, Freeman ME, Stoker DA, Quardt SM, Cohen R, Hirsch EM. One stage mastopexy with breast augmentation. A review of 321 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(6):1674-1679.

5 Spear SL, Boehmler JH, Clemens MW. Augmentation/Mastopexy: a 3 year review of a single surgeon’s practice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7S Suppl):136S-147S.

6 Handel N. Secondary mastopexy in the augmented patient: A recipe for disaster. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7S Suppl):152S-163S.

7 Spear SL, Carter ME, Ganz JC. The correction of capsular contracture by conversion to dual-plane positioning: technique and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 118(7S Suppl), 2006.

8 Regnault P. Breast ptosis. Definition and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1976;3(2):193-203.

9 Graf R, Biggs TM. In search of better shape in mastopexy and reduction mammoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(1):309-317.

10 Benelli LC. A new periareolar mammaplasty: The ‘round block’ technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 1990;14:93.

11 Hammond DC, Khuthaila DK, Kim J. The interlocking Gore-Tex suture for control of areolar diameter and shape. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(3):804-809.

12 Panchapakesan V, Brown MH. One stage correction of the tuberous breast with anatomic cohesive silicone gel breast implants. Aesth Plast Surg. 2009;33(1):49-53. Epub 2008 Aug 28

13 Brown MH, Shenker R, Silver SA. Cohesive silicone gel breast implants in aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(3):768-779.