44 Primary and Acquired Immunodeficiency Disorders

The initial eight cases of pediatric acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) were reported in 1983 from the Pediatric Allergy-Immunology and Infectious Disease program in Newark, New Jersey, initially named the Children’s Hospital AIDS Program (CHAP).1 When the children’s hospital closed in 1998, the Pediatric HIV/AIDS program was renamed the François-Xavier Bagnoud Children Center. One of the cases from this initial cohort best illustrates the recognition that these infants and children were part of the AIDS epidemic and not a sudden increase in a new form of primary severe combined immunodeficiency disorder (SCID).

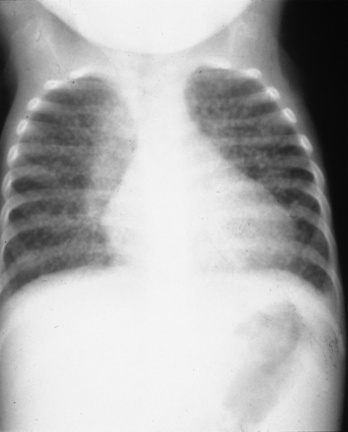

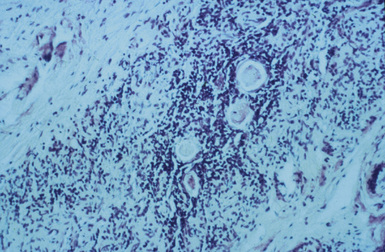

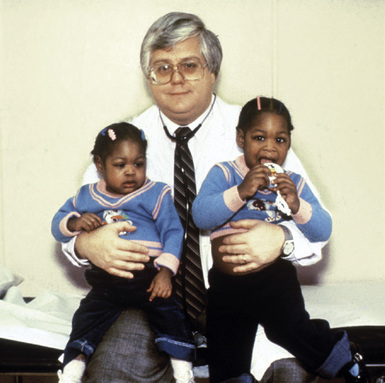

A 4-month-old girl presented with chronic diarrhea, leading to failure to thrive and wasting syndrome that was associated with recurrent and severe sino-pulmonary infections anemia, lymphopenia, generalized lymphadenopathy and thrombocytopenia. She was under the supervision of New Jersey’s Division of Youth and Family Service (DYFS) by a foster mother, because of abandonment by her chronically ill intravenous drug-using mother. Her initial immunologic laboratory evaluation showed a surprising hypergammaglobulinemia instead of the expected hypogammaglobulinemia, low total T cells and, as was typical for that era, low markers by immunoflorescent microscopy for helper T cells. A lung biopsy was done for chronic infiltrates. During the procedure there was little thymus tissue noted and a small piece was obtained for pathologic evaluation. The lung biopsy demonstrated severe lymphocytic iterstitial pneumonia (LIP) (Fig. 44-1) and the thymus biopsy was reported as showing chronic inflammation, calcified Hassall bodies with marked reduction in thymus lymphocytes. These changes were unexpected and consistent with a probable chronic perinatal infection (Fig. 44-2). Most importantly, she had an identical second-born twin sister who was and remains healthy (Fig. 44-3). Over time, HIV/AIDS was confirmed in the ill twin while her identical twin sister remained well and thriving with consistently negative HIV assays. Both are now 30 years old and the HIV-infected sibling has survived despite progression of her HIV to AIDS. Until specific HIV diagnostic studies became available, the care team, including one of the coauthors of this chapter (JO), diagnosed differentiated perinatal HIV from the assumed initial diagnosis of SCID, based on the unexpected results of lung and thymus tissue and the discordant clinical course of the twins.

Epidemiology of Inherited and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndromes in Childhood

Approximately 55,000 children, newborn to age 19, die in the United States annually, with nearly half of these deaths being infants, of which two thirds are neonates.2 These infant mortalities are mostly due to prematurity as well as congenital and/or genetic abnormalities, both having primary or secondary immune dysfunction. Most of these secondary immune problems in the premature infant are related to innate immune dysfunction that include breaks in skin and mucus membrane integrity, nutritional deficiencies, exposure to nosocomial infectious agents and exposure to frequent procedures and broad-spectrum antibiotics. In older children, worldwide mortality has been decreasing, with most deaths attributed to chronic, life-limiting medical conditions. Primary and secondary immunodeficiencies in infants contribute considerably to infant mortality and pose a significant, but often not recognized, threat to the health and well-being of children in the United States.

Primary or inherited immunodeficiencies are almost always genetically determined, often confined to a few rare, familial, monogenic, recessive traits that impair the development or function of one or several leukocyte subsets and result in multiple, recurrent, opportunistic infections during infancy. With improved diagnostic capabilities and an increased understanding of human immune functions, these immunodeficiencies are proving to be more common than previously estimated and may affect a much larger population because of a broadening of the definition of primary immunodeficiencies (PID). Considerable expansion of the understanding of immunological changes is being demonstrated in multiple chronic diseases, as well as improved survival with more effective treatments (Table 44-1).3 The frequency of PID varies in different countries, with certain populations having higher frequency of some specific PID mutations.4 Progress in medical care has made it possible for many of these children with PID to survive to adulthood with symptoms and complications that may not be recognized by adult primary care providers.5

TABLE 44-1, A Classification of Primary Immune Disorders That Manifest in Neonates

| Components of the immune disorder | Immune system | Inheritance / associated features |

|---|---|---|

| Predominant antibody defects |

Notarangelo L et al. International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee on Primary Immunodeficiencies: Primary immunodeficiencies: 2009 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009: 124:1162 –1178.

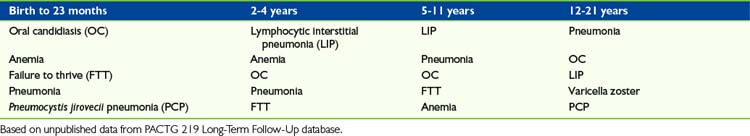

Secondary or acquired immunodeficiencies are more common than primary disorders of immune function (Table 44-1, B). By far, the most common secondary immunodeficiency of this era is HIV/AIDS.6 Based on the original version of the PACTG 219 follow-up study from 1993 through 2000, Table 44-2 lists the most common diagnosis during that period when HAART therapy was not available.7 Unfortunately, children presenting with these diagnoses at birth through 4 years also experienced the highest mortality rate. In the older age groups, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) remained associated with a high mortality rate but lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) was a marker for prolonged survival before HAART therapy.8 Sadly, during the early epidemic, despite a high morbidity and mortality rate, most attention was focused on treatment of opportunistic infections with little attention given to palliative and supportive care.

TABLE 44-1, B Classification of Immune Disorders Associated with or Secondary to Other Diseases

| Disease | Immune disorder | Inheritance / associated features |

|---|---|---|

| Bloom syndrome | Reduced T-cell function and decreased IgM | AR/LBW, retarded growth, facial telangiectasia, sun-sensitive erythemia, increased susceptibility to malignancies, molar hypoplasia, bird-like face/ rare |

| Fanconi anemia | Decreased T lymphocyte and natural killer (NK) cell function, decreased IgA | AR/multiorgan defects, bone marrow failure, café au lait spots, limb defects, abnormal faces, hyperpigmentation |

| Xeroderma pigmentosa (XP with 7 subgroups A-G and a variant, XPV) | Decrease in CD4+ levels and function due to mutation of the DNA repair gene for ultraviolet (UV) induced damage. | AR/defect in nucleotide excision repair (NER) with mutations of important tumor suppressor genes (e.g., p53 or proto oncogenes) leading to a sixfold increase in metastatic malignant melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma as well as XP being six times more common in Japanese people |

| Cancers | Bone narrow suppression from tumor infiltration or ablation of marrow from therapy: drugs or radiation | An increasing number of cancers appear to be enhanced by specific genetic characteristics |

| Malnutrition | Both single nutrient/trace metal impact on specific immune function or generalized wasting | AR/acrodermatitis enteropathica (zinc deficiency) |

| Infections | Varies with organism and whether localized/systemic or acute/chronic | Chronic, multiorgan system viral infections predominate, penultimate example being HIV/AIDS |

| Prematurity | Greatest impact on innate host defenses | More profound when gestation <28 weeks because of sharp drop in maternal-to-fetus transfer of immunoglobulins |

| Chronic organ system diseases: diabetes or renal disease | Like infections, great variations with severity depending on single or multiple organ involvement, timing of onset | Depending on organ systems or specific cause of organ failure, there may be a genetic-linked immuno deficiency syndrome |

Globally, an estimated 430,000 children younger than 15 were newly infected with HIV in 2008. The vast majority of these children (90%) acquired the virus via perinatal/mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). By the end of 2008, 2 million children were infected with HIV worldwide, with 280,000 children dying of the disease in that same year.9 In the United States, HIV has become the sixth-leading cause of death among 15-24 year-olds,10 and continues to disproportionately affect people of color. African Americans, who account for only 13% of the U.S. population, represent 51% of the estimated number of HIV/AIDS diagnoses made through 2007.11

HIV is also transmitted via other routes, such as through blood transfusions as evidenced in the hemophilia population. Before the policies for screening HIV in blood supplies were instituted, many people were exposed to the virus through intravenous transfusions of blood or blood products. People with hemophilia routinely need certain blood-clotting components, and receive them through frequent blood transfusions. From 1978 through 1985, many hemophiliacs were inadvertently put at extremely high risk for acquiring HIV through the public blood supply. Hemophiliacs now represent 1% of all people with AIDS in the United States.12

The final group of children who acquire HIV are victims of sexual abuse. A small percentage of children (<1%) acquire HIV through sexual abuse by an infected adult male, usually a relative or close friend of the family. Because sexual abuse of children is likely to be under-recognized and under-reported, sexually abused children are not routinely screened for HIV infection, and sexually abused children infected with HIV who have not progressed to AIDS are not reported in many states, the full extent of sexual transmission of HIV among children is not known.13 It is important to also note that among adolescents ages 15 to 19, the major cause of HIV infection is through high-risk sexual activity.

Symptoms, Distress, and Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Immunodeficiency Disorders

Clinical manifestations of HIV in children include recurrent bacterial infections; recurrent and intercurrent opportunistic infections; neuro-psychiatric manifestations; gastrointestinal problems, such as diarrhea and malnutrition; weight loss; respiratory problems, such as pneumonia and bronchiectasis; and skin manifestations, such as herpes simplex, seborrhoeic eczema, and molluscum contagiosum. Other problems include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, oral candidiasis, failure to thrive, wasting syndromes, parotitis, malabsorption, and developmental delays and/or loss of developmental milestones.14 Acute, chronic, and recurrent pain may be related to the disease, to progression, and/or to medications, treatments, and procedures.

Children and adolescents with HIV experience more subjective distress than their uninfected peers, including dysphoria, hopelessness, preoccupation with their illness, and poor body image related to their physical appearance affected by wasting and dermatologic conditions. “Attempting to cope with HIV-positive serostatus may trigger social withdrawal, depression, loneliness, anger, confusion, fear, numbness, and guilt.”10 Children in particular may believe that they did something terrible to deserve HIV, resulting in the development of guilt. “Non-infected siblings are also affected by HIV. Sibling relationships may be damaged by a fear of contagion or feelings of resentment towards the ill child. Because of these multiple difficulties, siblings of infected children also often experience problems in school.”10

In addition to increased distress, adolescents with HIV often experience greater physical pain, which is a frequent accompaniment to AIDS. Almost 60% of children with HIV experience pain, which may negatively affect their quality of life and sleep patterns. Chest pain, headache, oral cavity pain, abdominal pain, and peripheral neuropathy are commonly reported. As in other chronic illnesses, pain needs to be understood within a developmental context so that preventive and therapeutic intervention strategies can be developed to reduce children’s distress.10

Treatment

Treatments for HIV-1 disease complications that improve quality of life include HAART, prevention of bacterial infections, and the provision of prophylaxis and treatment of opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia(PCP), atypical mycobacteria infection (MAC), cryptococcal meningitis, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus. Good nutrition is a critical component in health maintenance and quality of life.15,16 These measures, in addition to good supportive care, have slowed the progression of HIV infection. As a result, many more HIV-infected children are now living longer, well into their teens. Palliative care needs to be integrated with cure-directed therapy and should be available from diagnosis through the entire course of the disease.

Although HAART dramatically changed the outcome for many HIV-infected children in developed countries, problems with adherence to or tolerance of therapy, and the increasing viral resistance rate to multiple antiretroviral drugs suggest that the need for palliative, respite, and hospice care for HIV-infected children will increase. The picture in the resource-poor areas of the world is very different. More than 90% of HIV-infected children who reside in these countries lack access to many therapies such as HAART, PCP, or MAC prophylaxis, that would prevent disease progression and are considered part of the continuum of palliative care.17,18

HIV disease-related pain

HIV disease-related pain results from both infectious and noninfectious processes in various organ systems that can be acute or chronic. Causes of oropharyngeal pain include candidiasis, dental problems, periodontitis, gingivitis, aphthous ulcers, and herpetic stomatitis.19 Esophageal pain, or dysphagia, can result from esophageal candidiasis, CMV, or herpetic ulcerative esophagitis. A rare cause of dysphagia may be lymphoma. Common causes of abdominal pain include pancreatitis, hepatitis, cholengitis, MAC enteritis or colitis, CMV colitis, and inflammatory or infectious colitis. Chronic diarrhea, although not classically considered a pain syndrome, is common in HIV disease and is usually associated with abdominal discomfort, including cramping and spasms.20,21

The oropharyngeal and gastrointestinal pain syndromes frequently result in poor oral intake and reduced absorption of nutrients, which lead to malnutrition and failure to thrive, and progresses to wasting syndrome. Even in the early stages of HIV disease, the recurrent difficulty with oral intake from various causes may have a significant impact on quality of life. The wasting syndrome is commonly associated with cachexia, fatigue, depression, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, and neuropathy secondary to nutritional deficiencies. The chronic pain and suffering experienced by HIV-infected children with wasting syndrome is one of the most challenging pain syndromes to effectively treat and relieve.15,19,21

Neurologic and neuromuscular pain syndromes are relatively common in HIV-infected children. These include hypertonicity; spasticity; encephalitis, including herpes and toxoplasmosis; meningitis, such as Cryptococcus neoformans; primary CNS lymphoma; Guillain-Barre syndrome; and myopathy. Peripheral neuropathies, or the possibility that the neuropathy might be a drug side effect such as to an antiretroviral, should be remembered. Skin and soft tissue complications of HIV, which are associated with both acute and chronic pain and discomfort, include herpes simplex, shingles, and other bacterial or fungal infections, as well as adenitis caused by bacterial or mycobacterial agents. Malignancies such as leukemia, lymphoma, and leimyosarcoma, which seem to be more frequent in HIV-infected children, have cancer-associated pain syndromes in addition to the HIV-associated symptoms.19,20

HIV treatment-related pain

Some chronic pain experienced by HIV-infected children is related to the side effects and toxicities of the multiple medications used, especially antiretroviral medications. A detailed description of the specific side effects of each antiretroviral is available in published pediatric treatment guidelines.22 Many of the antiretroviral medications cause abdominal discomfort, nausea, and diarrhea. This is especially true for the protease inhibitors as a class, but is also seen with nucleoside analogues, such as didanosine and zidovudine. Other painful side effects associated with antiretroviral drugs include headache, pancreatitis, and neuropathy. Patients often need to continue the medications causing these symptoms and are asked to live with these side effects or risk development of drug resistance and disease progression. In addition to the pain associated with antiretroviral therapy, the stress of adherence to these complex regimens has its own adverse impact on quality of life.22

Management of pain in the child with HIV

Many physicians are preoccupied with managing the HIV disease and prolonging life, and frequently neglect to alleviate suffering from adverse effects of the disease, treatment interventions, or procedures. One of the major limitations in preventing HIV-infected children from receiving appropriate palliative care is the lack of appreciation of both acute and chronic pain associated with this disease and the multiple painful procedures required in the management of this syndrome.20 In addition, physicians are not well trained in pain management, particularly in patients with chronic illnesses that result in both somatic and neuropathic pain.

The goals of pain management in HIV-infected children include:

Special Considerations Unique to Children and Adolescents with HIV/AIDS

Advances in therapies have led to “survival past 5 years of age for more than 65% of infected children.”10 A majority of these children and adolescents, most of whom contracted HIV via MTCT have lived beyond childhood. With this, caregivers and healthcare providers face the troubling issue of HIV diagnosis disclosure to affected children and adolescents, as well as the array of issues that accompany HIV infection such as stigma and physical and mental signs and symptoms.10

Cognitive concerns

Although many children are asymptomatic, numerous studies document the occurrence of at least some cognitive and language delays as a result of HIV. These cognitive manifestations, though subtle, do impact the quality of life for children with HIV. The mechanism of brain impairment because of HIV is not completely understood. Three patterns of abnormal neurocognitive development have been described: rapid progressive encephalopathy (PE) with loss of attained milestones, subacute progression of encephalopathy with relatively stable periods, and static encephalopathy with a failure to achieve new milestones.10

Social stigma and other issues

There are major differences in HIV illness that make it difficult to apply evidenced-based knowledge being practiced within other pediatric illness sectors. These differences lie in epidemiology, the multigenerational nature of HIV, and the social stigma surrounding HIV transmission. Pediatric HIV is most prevalent in poor, urban, and ethnic minority populations who have typically suffered years of discrimination and racism. Moreover, HIV infection is associated with stigmatized behaviors such as high-risk sex, same-sex behavior, drug use, and fear of contagion, which have all contributed to a level of stigma beyond that associated with any other disease. “The majority of HIV-infected children acquired the virus from their mothers, and ensuing parental guilt about transmission distinguishes this disease from cancer and other life-threatening pediatric illnesses.”25

Frequently, children with HIV come from families with a history of substance abuse, which sometimes causes clinicians to fear using opioids to treat these children. Clinical experience has shown that with proper monitoring and systems put in place, the incidence of addicted caregivers using a child’s medication is extremely low. Fear of parental misuse is not a reason to withhold opioids from a child in pain.26

Disclosure

Unlike disclosing a cancer or other life-limiting disease, disclosure of a child’s HIV diagnosis often leads to disclosure of other family secrets, including paternity, parental history of sexual behavior, and substance abuse. “Thus, not only are parents’ decisions to disclose affected by their fears about the emotional consequences of disclosure for the child, but also their fears about the child’s anger towards the parent, and the potential social consequences associated with the child sharing the diagnosis with others (e.g., ostracism, negative reactions from family, friends, and school, lack of community support).”25 Disclosure of HIV status to young school-aged children who participate in sports should be addressed while maintaining the confidentiality and well-being of the child.

For children with HIV who know their diagnosis, the decision to disclose their status to friends, teachers, employers, and especially potential romantic partners has been a primary concern. For those unaware of their diagnosis, ethical and legal conflicts also arise.25 An example would be when there is a lack of concordance between parent and child readiness for disclosure of the child’s status, such as the parents don’t want to disclose and the child is beginning to engage in risk behavior, then what are the obligations of the provider? Many providers will not disclose to the child if the parents do not want disclosure to occur out of both respect for parents wishes and concerns that parents will remove the child from treatment. However, as children age, providers become increasingly uncomfortable with secrecy, particularly when adherence and sexual behavior are issues. At this time, there are limited laws or practice guidelines for providers to consult in these situations.25

The process of disclosure should be conceptualized as an ongoing dialogue among the youth, family, and healthcare providers about the impact of HIV infection. The process must reflect the child’s developmental understanding of illness and death over time.25 An important goal throughout is to establish and maintain developmentally appropriate youth participation with the recommended complex medical regimen.27 A conceptual framework to address the process of disclosure highlights five steps:28

Interdisciplinary Care of Children with Immunodeficiency Syndromes

An example of a core Interdisciplinary Pediatric Palliative Care Team (IPPCT) approach to the care of a children with HIV and family is in Box 44-1.29

| Child and family | Participates actively in identifying values, hopes, fears, and dreams, assists clinicians to establish goals that are based upon their wishes; communicates conflicts, identifies evolving needs. The child-family unit is the focus and driving force of team activities. |

| Physician(s) | Aligns with family to develop a plan that is in the best interests of the child; consults with HIV and other physician specialists; provides expert advice on pain and symptom management, communication, anticipatory guidance, treatment decisions, and end-of-life care. |

| Advance practice nurse | Evaluates patient and family understanding of illness, symptoms, medication regimens, treatment options, and prognosis. Educates family and assists them to understand decisions to be made, along with consequences, both short and long term. Empowers family to develop effective partnerships with clinicians. Acts independently, with prescriptive privileges in accordance with state statutes, interfaces with physician colleagues, functions as a change agent.* |

| Nurse clinician | Evaluates patient well-being, monitors patient response to pain and symptom management, and assesses family coping mechanisms. Assesses family realities in relation to adherence. Identifies confusion, fears and barriers to compliance. Reinforces adaptive coping, explores negative consequences of maladaptive coping responses. Acts as clinician, educator, consultant to families, bedside clinicians, and community providers. |

| Social worker | Identifies family’s culture, strengths, challenges, roles, patterns of communication, and ability to adequately care for the child. Assists family to access transportation, address housing needs, reimbursement for equipment and supplies not covered by insurance. Provides emotional support and refers to appropriate social, community, and child protection agencies, when needed. |

| Bereavement counselor | Provides anticipatory guidance to family and clinicians, coordinates after-death care to parents, siblings, extended family and community groups; develops culturally sensitive systems of follow-up and support; identifies families at risk; provides support for clinicians’ grief; provides community outreach services. |

| Pastoral care | Provides spiritual support and guidance. Assists family to access clergy from a requested denomination. Assists with the implementation of rituals and display of significant symbols. Assists family to explore meaning, resolve guilt, and express forgiveness. Explores beliefs about suffering and existence of afterlife. |

* Ferrell B, Coyle N: Textbook of palliative nursing, New York, 2006, Oxford University Press.

HIV End Stage and End-of-Life Concerns

Judicious use of antiretroviral therapy may improve the quality of life by minimizing the impact of opportunistic infections and sustaining a measure of immunologic health. At the end-stage of HIV disease, decisions relating to the continuation of antiretroviral therapy must be made balancing the limited effect of such treatment versus drug side effects and toxicities. At the end of life, however, aggressive treatment of symptoms is a requisite of good palliative care. For example, the prevention of Pneumocystis pneumonia with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis provides comfort by avoiding the substantial morbidity of this infection. Clinicians need to recognize when the burden of treatment outweighs the benefits, and when the continuation of curative treatment is not only ineffective, but also a source of greater suffering for the child.30,31

Bereavement Needs of Families and Healthcare Providers

Challenges for children with HIV/AIDS

Little is known from research specifically about the impact of child deaths due to HIV/AIDS or interventions to help families cope with such a loss.31 As with other chronic, life-threatening illnesses, however, initiating bereavement care before end of life supports both the child and family in important ways, especially by dealing with the child’s awareness of his or her own impending death, optimizing the quality of life.32 Inquiring about and understanding the cultural and spiritual preferences and beliefs of the family are critical. Based on such an understanding, interventions by the palliative care team include:

Following the death of a child with HIV/AIDS, responding appropriately requires sensitivity to individual, familial and cultural differences related to grief and mourning. The death of any child challenges one’s assumptive view of the world, including how one engages in meaning making. Making meaning facilitates resilience following a death and has two components.33 One is making sense of the loss, for example, acknowledging that “she’s no longer in pain” or “he won’t have to suffer anymore.” The other is finding some benefit in the aftermath of the loss, for example, improved family communication, positive change in lifestyle, becoming involved in a social cause. Employing strategies to help families through their personal meaning making process, including using their religious and spiritual bonds, is one way to support their grief journey.

Supporting healthcare providers for children with HIV/AIDS

In research assessing end-of-life care,34 healthcare professionals who care for children with life threatening conditions were found to themselves suffer not only in grief over the child’s circumstances, but also because of role conflicts, or situations that caused moral distress or loss of professional integrity. In some instances they were called upon to act in a manner contrary to personal and professional values causing ethical dilemmas. Additional stressors included communication difficulties with young patients and parents, team conflicts, and the inadequacy of support systems for care providers.35 Although care providers can experience feelings of being overwhelmed, a commonsense approach to addressing and meeting their basic needs, that is rest, nutrition, and exercise, is obvious but often overlooked. Systemic interventions to address these stressors include building a community to support the work of healthcare providers through regular meetings and intensive training sessions, and implementation of palliative care rounds, patient care conferences, and bereavement debriefings.

1 Oleske J.M., Minnefor A.B., Cooper R., Thomas K., de la Cruz A., Ahdieh H., et al. Immune deficiency syndrome in children. JAMA. 1983;17:2345-2349.

2 Institute of Medicine, Field M.J., Behrman R.E., editors. When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2003.

3 Casanova J., Abel L. Primary immunodeficiencies: a field in its infancy. Science. 2007;317:617-619.

4 Notarangelo L., et al. International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee on Primary Immunodeficiencies: Primary immunodeficiencies: 2009 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1162-1178.

5 Casanova J., Fieshi C., Zhang S., Abel L. Revisiting human primary immunodeficiencies. J Intern Med. 2008;264:115-127.

6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV AIDS Surveill Rep. 2000;12(2):1-44.

7 Oleske J.M., Ruben-Hale A., Supportive Care Quality of Life Committee. Enhancing supportive care and promoting quality of life: Clinical Practice Guidelines. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG). Pediatric AIDS & HIV infection: fetus to adolescent. 1995;6(4):187-203.

8 Joshi V.V., Oleske J.M. Pulmonary lesions in children with AIDS: A reappraisal based on data in additional cases and follow-up of previously reported cases. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:641-642.

9 WHO Global Summary of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Dec. 2009. www.who.int/hiv/data/2009_global_summary.gif. Accessed February 17, 2010

10 Brown L.K., Lourie K.J., Pao M. Children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS: a review. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2000;41:81-96.

11 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Glance at the HIV/AIDS Epidemic: CDC HIV/AIDS Fact Sheets. June 2007. www.cdc/hiv/resources/factsheets/us.htm. Accessed February 17, 2010

12 AIDS.org. Hemophilia and HIV: A Double Challenge. http://www.aids.org/atn/a-102–02.html Accessed February 18, 2010

13 Lindegren M.L., Hanson C., Hammett T.A., Beil J., Fleming P.L., Ward J.W. Sexual abuse of children: intersection with the HIV epidemic. Pediatrics. 1998;102(4):e46.

14 Norval D., O’Hare B., Matusa R. HIV/AIDS. In: Goldman A., Hain R., Liben S., editors. Oxford textbook of palliative care for children. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006:467-480.

15 Oleske J.M., Rothpletz-Puglia P.M., Winter H. Historical perspectives on the evolution in understanding the importance of nutritional care in pediatric HIV infection. J Nutr. 1996;126:2616S-2619S.

16 Oleske J.M. Preventing disability and providing rehabilitation for infants, children and youths with HIV/AIDS. Bethesda, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, January 1995. NIH publication no. 95–3850

17 World Health Organization. The World Health Report 1995—Bridging the Gap. Report of the Director-General.

18 Oleske J.M. The many needs of the HIV-infected child. Hosp Pract. 1994;29:81-87.

19 Connolly G.M., Hawkins D., Harcourt-Webster J.N., et al. Oesophageal symptoms, their causes, treatment and prognosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Gut. 1989;30:1033-1039.

20 Czarniecki L., Boland M., Oleske J.M. Pain in children with HIV disease. PAAC Notes. 1993;5:492-495.

21 Hirschfeld S., Moss H., Dragisic K., et al. Pain in pediatric human immunodeficiency virus infection: incidence and characteristics in a single- institution pilot study. Pediatr. 1996;98:449-456.

22 The Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection,. 14 December. 2001. update available at www.hivatis.org

23 McGraft P.J., Finley G.A. Attitudes and beliefs about medication and pain management in children. J Palliat Care. 1996;12:46-50.

24 Zelzer L.K., Altman A., Cohen D., et al. Report of the subcommittee on the management of pain associated with procedures in children with cancer. Pediatr. 1990;86:826-831.

25 Wiener L., Mellins C.A., Marhefka S., Battles H.B. Disclosure of an HIV diagnosis to children: history, current research, and future directions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28:155-166.

26 Schechter N.L., Bernstein B.A., Beck A., et al. Individual differences in children’s response to pain: role of temperament and parental characteristics. Pediatr. 1991;87:171-177.

27 Gerson A.C., Joyner M., Fosarelli P., Butz A., Wissow L., Lee S., Marks P., Hutton N. Disclosure of HIV diagnosis to children: when, where, why, and how. J Pediatr Health Care. 2001;15:161-167.

28 Carter B.S., Oleske J., Czarniecki L., Grubman S. The child with HIV infection. In: Carter B.S., Levetown M., editors. Palliative care for infants, children, and adolescents: a practical handbook. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004:337-339.

29 Ferrell B., Coyle N. Textbook of palliative nursing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

30 Oleske J.M., Czarniecki L. Continuum of palliative care: lessons from care for children infected with HIV-1. Lancet. 1999;354:1287-1291.

31 Demmer C. Children and infectious diseases. In: Corr C., Balk D., editors. Children’s encounters with death bereavement and coping. New York: Springer, 2010.

32 Stevens M., Rytmeister R., Proctor M., Bolster P. Children living with life-threatening or life-limiting illnesses: a dispatch from the front lines. In: Corr C., Balk D., editors. Children’s encounters with death bereavement and coping. New York: Springer, 2010.

33 Neimeyer R. Meaning and reconstruction and loss. In: Neimeyer R., editor. Meaning reconstruction and the experience of loss. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2001.

34 Rushton C., Reder E., Hall B., Comello K., Sellers D., Hutton N. Interdisciplinary intervention to improve pediatric palliative care and reduce health care professional suffering. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:922-933.

35 Liben S., Papadatou D., Wolfe J. Paediatic palliative care: challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet. 2008;371:852-864.