Pressure on nerves

Anatomy

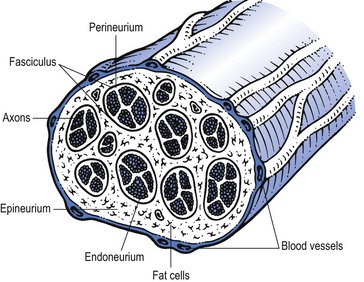

Peripheral nerves contain both neural and supportive elements. A large multifascicular nerve is composed of a number of different bundles of nerve fibres or fasciculi (Fig. 2.1). These are bound together by the epineurium, a condensation of areolar connective tissue derived from the mesoderm. In humans, the epineurium normally constitutes 30–50% of the total cross-sectional area of the nerve bundle: it contains fibroblasts; collagen (types I and III); variable amounts of fat (possibly to cushion the nerve fibres it surrounds); lymphatic; blood vessels (vasa vasorum); and free nerve endings. In a monofascicular nerve, the epineurium only surrounds the fasciculus and is fused with the perineurium.

The perineurium surrounds and protects one fascicle. It has two different layers; an outer collagen-rich connective one and an inner epithelial layer of contiguous cells. The perineurium has an important role in maintaining the osmotic milieu and fluid pressure within the endoneurium and also acts as a barrier against chemical and bacterial invasion.1

The connective tissue of peri- and epineurium possesses blood and lymph vessels – the so-called vasa vasorum.2,3 Also free nociceptive nerve endings which come from the related multifascicular nerve trunks are embedded in the perineurium and epineurium.4,5

Enclosed in the perineurium is the fasciculus – a bundle of nerve fibres bound together and protected by the endoneurium. The latter consists of long collagen fibres running with the nerve fibres. The fibrous and cellular components of the endoneurium are bathed in endoneural fluid.6

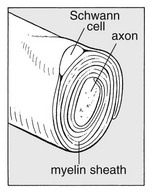

The nerve fibres are axons – the distal offshoots of nerve cells (Fig. 2.2). Most axons are surrounded by a myelin sheath formed from the compressed and concentric Schwann cell membranes. Axons range in diameter from 0.2 µm (small non-myelinated nociceptive axons) to 20 µm (large and myelinated efferent motor axons) and in length from 1 to 100 cm. They contain most of the cell volume.

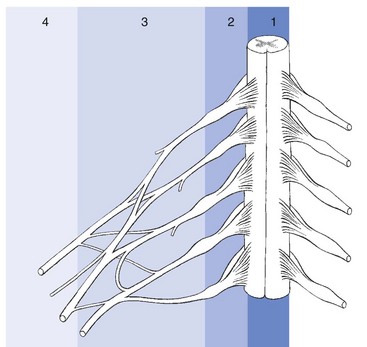

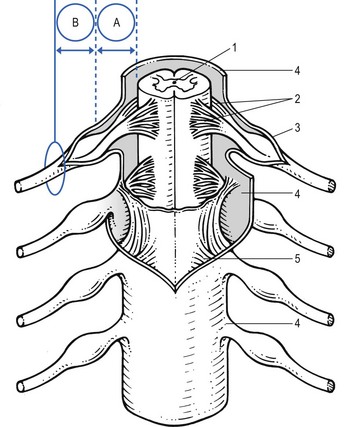

From central to peripheral, the nervous system can be clinically divided into four zones (Fig. 2.3):

• The spinal nerve, which contains fibres belonging to one segment

• In the brachial and sacral area, and distal from the spinal ganglion, the different spinal nerves form a nerve plexus, from which originate the large multifascicular nerve trunks

• Further distally the trunks split into peripheral nerves, with motor, sensory or combined function.

Roots

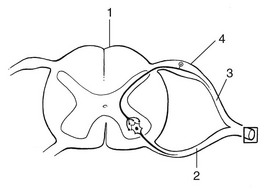

The course of the spinal nerve within the spinal canal, from the emergence of the rootlets at the anterior and posterior aspect of the spinal cord to the outer border of the foramen, is called the intraspinal root (Fig. 2.4).7 Being inside the meningeal membranes of the spinal cord, the posterior and anterior roots are devoid of the elaborate epineural and perineural membranes that are characteristic of peripheral nerves.

Proximally, the rootlets float freely within the cerebrospinal fluid which is the main source of their metabolic needs. In this intrathecal part of the intraspinal root, the rootlets are held together by the endoneurium which is more loosely arranged than is typically seen in peripheral nerves.8 Further distally, the nerve root becomes enclosed in the dural sheath – a tubular prolongation of the dura. In this dural investment the nerves do not lie freely but are bound by the arachnoid membrane (Fig. 2.5).9,10 This area is known as the extrathecal part of the intraspinal nerve root – that length of the root and the dural sleeve between the main dural sac and the exit from the foramen. The extrathecal portion is short in the cervical region but becomes longer with the increasing obliquity of the intraspinal roots in the thoracolumbar and lumbar regions.

The segment of the spinal root which is liable to compression, whether by a disc protrusion, an osteophytic outgrowth or a narrow lateral recess, is the extrathecal part of the intraspinal root. To understand the symptom of a compression or inflammation of this part of the peripheral nerve system, it is necessary to recognize the importance of the dural investment – the nerve root sheath. The dural sheath has considerable sensitivity:11 it has many nociceptive nerve endings, especially at the anterior aspect where it receives its innervation from the sinuvertebral nerve belonging to the same segment.12–14 Pain arising from the dural sheath is segmental and obeys the rules of segmental reference of pain (see Ch. 1). There is no evidence that root pain arises from involvement of the axons. For example, pressure at the extraspinal nerve root, which misses the nerve root sleeve, as happens in some types of spondylolytic compression, causes not pain but only paraesthesia and neurological deficit.

Nerve plexus and nerve trunk

Immediately distal to the foramen, the single fasciculus of the extraspinal root is enclosed in a thin, but strong, perineurial sheath, external to which is the epineurial areolar connective tissue. Within a few millimetres of its formation, the single fasciculus of the spinal nerve divides into several bundles which form the plexuses. Motor and sensory fibres of one nerve root mix, and more distally there is a redistribution of the fasciculi of various consecutive nerve roots.15 The brachial plexus is thus formed of the anterior rami of roots C5–T2, and the sacral plexus of the roots L2–S5. Distally, the fasciculi continue in the large nerve trunks of the limbs.

The fasciculi of plexus and trunks do not differ significantly from those of the roots or the peripheral nerves. The connective support tissue, however, has some anatomical particularities. Because the monofascicular spinal nerve changes into a multifascicular structure, there is an increased amount of epineurial tissue, forming a protective packing for the nerve tissue. The perineurium is also reinforced by elastin fibres. The fasciculi have an undulating course, whereas the collagen fibres run more longitudinally. This structure ensures that the nerve fibres are protected from mechanical deformation (compression and elongation) during normal movements of the limbs.16 Although the epi- and perineurium contain nociceptive nerve endings, these seem to be relatively insensitive.17

Terminology

Lesions of the peripheral nervous system are characterized by a pathognomonic sensation: paraesthesia (‘pins and needles’). Although all tissues in the human body which contain nociceptive structures can be a source of pain, pins and needles will only arise when some part of the peripheral nervous system is at fault. Hence, the medical world tends to use the term ‘neuritis’ when pain is accompanied by pins and needles. Strictly, however, the suffix ‘-itis’ implies inflammation. Therefore the word neuritis should only be used when the peripheral nerve is affected by infectious or toxic irritation – i.e. there is an intrinsic disorder of the nervous parenchyma. Classically, these lesions are classified into mono- and polyneuritis. They are not discussed in this book, except in the shoulder region, where the clinical appearance of three mononeurites and neuralgic amyotrophy of the shoulder girdle is reviewed (see online chapter Nerve lesions and entrapment neuropathies of the upper limb).

Pain originating from the peripheral nerve system

Nociceptive pain

Peripheral nociceptors in the connective tissue of the peripheral nerves are stimulated, and via Ad and C fibres of the nervi nervorum conducted to the spinal cord and thence to the pain projection areas in the cortex.18 There are indications that most of the pain that stems from direct irritation of the peripheral nervous system is of nociceptive origin.19,20 ‘Nerve pain’ thus behaves identically to other peripheral pain,21 obeys exactly the rules of referred pain and is not to be distinguished from pain of ligamentous, tendinous or arthrogenic origin (see Ch. 1).

Neuropathic pain

This type of pain, also called ‘de-afferentation or neuralgic pain’ is less common than nociceptive pain and results from prolonged damage to peripheral nerve tissue, such as avulsion, dissection or amputation.22 The pain is felt in the anaesthetic area, is continuous and burning and is independent of posture or movement, although local pressure can increase the pain considerably.23

Chronic damage or formation of scar tissue seems to provoke pain mechanisms without involvement of peripheral nociception. Also, the formation of a neuroma leads to increased sensitivity and spontaneous pain.24 Research on experimental neuromata has shown that regenerating axons have a spontaneous excitability and an increased sensitivity to mechanical stimuli. An action potential in one axon probably leads to an impulse in a nearby axon. This mechanism of ‘cross-talking fibres’ accounts for the repetitive train of action potentials in a bundle of regenerating axons.25 A small stimulus thus leads to a self-perpetuating series of action potentials, and excessive and long-standing pain.26

Another mechanism that may account for neuropathic pain is the loss of inhibitory effects of the large diameter mechanoreceptor afferents in a traumatized nerve. This leads to a relative increase of the activity from the small nociceptive afferents, and thus an opening of the gate at the dorsal horn.27 (see Ch. 1).

Superficial dysaesthetic pain

This type of pain is also rare, and is typical of diffuse polyneuritis, for example in diabetes,28 vitamin B1 deficiency or chemical irritation. Damage to small C fibres leads to sprouting of small offshoots in the regenerating axons. This leads to increased excitability, which results in unpleasant painful sensations during normal stroking of the skin (allodynia).29 The patient also complains of a burning feeling and ‘electrical sensations’ when the skin is gently touched (dysaesthesia), and there is also some analgesia (see Box 2.1 for an overview of neurogenic pain).

Behaviour of nervous tissue during pressure

Entrapment of peripheral nerve tissue is defined as mechanical compression of the nerve, which includes the reduction of radial dimensions in the neural cells, the neural support elements or any combination of these. Depending on the degree and the duration of compression, the effects can be subtle or can lead to displacement, deformity and morphological changes in the compressed tissue (neural tissue or neural support tissue).30

The clinical effects of nerve compression are pain, paraesthesia and loss of function (see Box 2.2 for an overview of pressure on nerves).

Pain

The pain mechanism in entrapment phenomena is usually nociceptive: free nerve endings in the connective tissue of the nerve or in the dural investment of the nerve root are depolarized by application of mechanical forces or after exposure to irritating chemical substances, released from inflamed tissues.31 The pain stems from irritation of the support tissue enclosing the nerve fibres and only exceptionally does it result from pathological processes in the nerve tissue itself (neuropathic and dysaesthetic pain). This has the following clinical consequences.

Because an external force acts first on the outer supporting structures of the nerve, pain will usually be the first symptom and it sometimes appears before involvement of the parenchyma is present. A chronic but moderate pressure that is insufficient to impair conduction solely influences the outer structures and results in pain only. It is thus possible to have a completely normal examination of the peripheral nervous system, even though the patient does have nerve compression.32

Paraesthesia

Pins and needles are pathognomonic of involvement of the peripheral nervous system in that the sensation cannot be produced in any way other than compression or inflammation of nerve tissue.33 Paraesthesiae are always felt in the cutaneous area supplied by the nerve tissue involved and distal to the site of the lesion. It is therefore extremely important to ascertain the precise site of the symptom, in that this helps to determine the site of compression.

Loss of function

The epineurium and perineurium initially buffer the fasciculi from constrictive effects, but with a greater amount of compression, structural changes of the elements within the endoneurium follow.34 Recent research has demonstrated that the intraradicular oedema caused by alteration of the blood–nerve barrier is the most important factor in the nerve root dysfunction of chronic compression.35,36

If considerable compression is maintained for a longer period, atrophy of the nerve tissue occurs and is followed by Wallerian degeneration of the distal part of the axon. Oedema, cellular proliferation and ingrowth of connective tissue also follows.37 If the compression is maintained for long periods, fibrotic degeneration appears at the site of the lesion, which makes recovery most unlikely.38

Clinical syndromes

Cyriax39 (see his pp. 37–39) distinguished four different syndromes in entrapment phenomena, corresponding to the site of compression along the peripheral nerve: at the small peripheral sensory nerve, at the nerve trunk/plexus, at the nerve root and at the spinal cord (see Fig. 2.3).

Nerve trunk/plexus

There is also a relation between the duration of compression and the duration of paraesthesia. Thus, after 15 minutes of pressure, the pins and needles appear 20–60 seconds after the release and last only 1 or 2 minutes. After release from 15 hours’ compression, paraesthesiae will probably appear only after an interval of some hours, then persist for 1 to 2 hours before recovering spontaneously. Cyriax39 calls this strange and hitherto unexplained phenomenon the ‘release phenomenon’ (see his p. 37). Lundburg and Rydevik have demonstrated that fluctuations in membrane permeability of the structures within the endoneurium are more noticeable when compression on the nerve trunk is released and oedema appears, than during the compression of the nerve and its supplying blood vessels.40 This might explain the release phenomenon.

Compression of the nerve root

Pain

The nerve root has a dural sheath, which is innervated by the sinuvertebral nerve.12 The latter is derived from the corresponding nerve root. Therefore pain originating from the dural sheath is strictly segmental and follows the rules of segmental reference of pain. Compression applied to the dural sleeve of the nerve root thus results in pain occupying all or any part of the dermatome. Pain felt in a particular dermatome in combination with other symptoms of nerve compression, immediately draws attention to an impingement on the nerve root.

Deficit

The absence of the protective packing by epineurial tissue renders the nerve roots more susceptible to direct compression than nerve trunks. Compression disturbs nerve conduction by interfering with the blood supply of the nerve fibres.41 Loss of function of the nerve fibres results in sensory and motor deficit. Paraesthesiae usually disappear with the onset of cutaneous analgesia.

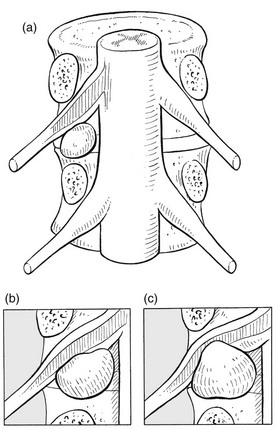

Progressive compression of a nerve root within its dural sleeve causes a typical sequence of symptoms: pain, paraesthesia and numbness will follow each other, rather than coincide. This is typically the case in a progressively increasing pressure exerted by an evolving disc lesion: slight compression on the epidural sheath of the nerve root causes pain only (Fig. 2.6a). As the pressure increases, paraesthesia and muscle fasciculations – symptoms of parenchymatous hyperexcitability – appear42 (Fig. 2.6b). In the final stage, pressure has induced such ischaemic damage to the nerve root that function is completely lost, including the conduction of pain (Fig. 2.6c). The patient then complains of weakness and numbness, but pain and paraesthesia have disappeared.

References

1. Shanta, TR, Bourne, GH, The perineural epithelium – a new concept. The Structure and Function of Nervous Tissue. Bourne, GH, eds. The Structure and Function of Nervous Tissue; vol. 1. Academic Press, New York, 1968.

2. Sjöstrand, J, Rydevik, B, Lundborg, G, McLean, WG. Impairment of intraneural microcirculation, blood nerve barrier and axonal transport in experimental nerve ischemia and compression. In: Korr IM, ed. The Neurobiologic Mechanisms in Manipulative Therapy. New York: Plenum Press, 1978.

3. McManis, PG, Low, PA, Lagerlund, TD. Microenvironment of nerve blood flow and ischemia. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Lambert EH, Bunge R, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1993:453–473.

4. Hromada, J, On the nerve supply of the connective tissue of some peripheral nervous system components. Acta Anat (Basel) 1963; 55:343–351. ![]()

5. Thomas, PK, Olsson, Y. Microscopic anatomy and function of the connective tissue components of peripheral nerve. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Lambert EH, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1975:168–189.

6. Low, PA. Endoneural fluid pressure and microenvironment of nerve. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Lambert EH, Bunge R, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1993:599–617.

7. Hollinstead, WH. Anatomy for Surgeons vol 3: The Back and the Limbs. New York: Harper & Row; 1969.

8. Sunderland, S. Traumatized nerves, roots and ganglia: musculoskeletal factors and neuropathological consequences. In: Korr IM, ed. The Neurobiologic Mechanisms in Manipulative Therapy. New York: Plenum Press, 1978.

9. Brieg, A, Biomechanics of the lumbosacral nerve roots. Acta Radiol (Diagn) 1963; 1:1141. ![]()

10. Haines, DE, Harley, HC, Al Mefty, O, The subdural space, a new look at an outdated concept. Neurosurgery 1993; 32:111–120. ![]()

11. Lindahl, O, Hyperalgesia of the lumbar nerve roots in sciatica. Acta Orthop Scand 1966; 37:367. ![]()

12. Edgar, MA, Nundy, S. Innervation of the spinal dura mater. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1966; 29:530–534.

13. Bogduk, N, The innervation of the lumbar spine. Spine 1983; 8:286–293. ![]()

14. Murphy, RW, Nerve roots and spinal nerves in degenerative disk disease. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1977; 129:46–60. ![]()

15. Sunderland, S. The anatomy of the intervertebral foramen and the mechanisms of compression and stretch of nerve roots. In: Haldeman S, ed. Modern Developments in the Principles and Practice of Chiropractice. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1979.

16. Sunderland, S. Nerves and Nerve Injuries, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1978.

17. Mumenthaler, M, Schliack, H. Läsionen peripherer Nerven. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1982.

18. Raja, SN, Meyer, RA, Campbell, JN, Peripheral mechanisms of somatic pain. Anesthesiology 1988; 68:571–590. ![]()

19. Asbury, AK, Fields, HL, Pain due to peripheral nerve damage: a hypothesis. Neurology 1984; 34:1587–1592. ![]()

20. Jänig, W, Kotzenburg, M, Receptive properties of pial afferents. Pain 1991; 45:77–86. ![]()

21. Casey, KL. Toward a rationale for the treatment of painful neuropathies. In: Dubner R, Gebhart GF, Bond MR, eds. Proceedings of the Fifth World Congress on Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988:165–174.

22. Tasker, RR, Tsudat, T, Hawrylyshyn, P. Clinical neurophysiological investigation of de-afferentation pain. Adv Pain Res Ther. 1983; 5:713–738.

23. Cecht, CHJ, Van de Brand, HJ, Wajer, O, Post-axillary dissection pain due to a lesion of the intercostobrachial nerve. Pain 1989; 38:171–176. ![]()

24. Wall, PD, Gutnick, M, Ongoing activity in peripheral nerves: the physiology and pharmacology of impulses originating from a neuroma. Exp Neurol 1974; 43:580–593. ![]()

25. Burchiel, KJ, Effects of electrical and mechanical stimulation on two foci of spontaneous activity which develop in primary afferent neurons after peripheral axotomy. Pain 1984; 18:249–265. ![]()

26. Govrin-Lippmann, R, Devor, M, Ongoing activity in severed nerves: source and variation with time. Brain Res 1978; 159:406–410. ![]()

27. Noordenbos, W, Wall, PD, Implications of the failure of nerve resection and graft to cure chronic pain produced by nerve lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1981; 44:1068–1073. ![]()

28. Brown, MJ, Marin, JR, Asbury, AK. Painful diabetic neuropathy. Arch Neurol. 1967; 33:137–141.

29. Thomas, PK. Painful neuropathies. Adv Pain Res Ther. 1979; 3:103–110.

30. Luttges, MW, Gerren, RA. Compression physiology: nerves and roots. In: Haldeman S, ed. Modern Developments in the Principles and Practice of Chiropractice. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1979:65–92.

31. Fields, HL. The peripheral pain sensory system. In: Fields HL, ed. Pain. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1987:13–40.

32. Cyriax, JH, Perineuritis. BMJ 1942; i:578. ![]()

33. Walton, JN. Essentials of Neurology, 6th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1989.

34. Lundborg, G, Structure and function of the intraneural microvessels as related to trauma, edema formation and nerve function. J Bone Joint Surg 1975; 57:938. ![]()

35. Yoshizawa, H, Kobayashi, T, Chronic nerve root compression. Spine. 1995;20(4):397–407. ![]()

36. Matsui, T, et al, Quantitative analysis of oedema in the dorsal nerve roots induced by acute mechanical compression. Spine. 1998;23(18):1931–1936. ![]()

37. Aguayo, A, Nair, CPV, Midgley, R, Experimental progressive compression neuropathy in the rabbit. Arch Neurol 1971; 24:358. ![]()

38. Luttges, MW, Kelly, PT, Gerren, RA, Degenerative changes in mouse sciatic nerves: electrophoretic and electrophysiologic characterizations. Exp Neurol 1976; 50:706. ![]()

39. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol. 1, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

40. Lundborg, G, Rydevik, B, Effects of stretching the tibial nerve of the rabbit. J Bone Joint Surg 1973; 55B:390. ![]()

41. Sunderland, S. Avulsion of nerve roots. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyen GW, eds. Injuries of the Spine and Spinal Cord (Handbook of Clinical Neurology, vol 25). New York: North-Holland, 1976.

42. Rasminsky, M. Ectopic generation of impulses in pathological nerve fibres. In: Jewett DL, McCarroll JrHR, eds. Nerve Repair and Regeneration – its Clinical and Experimental Basis. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1980:178–185.