2 Prescribing

Rational and effective prescribing

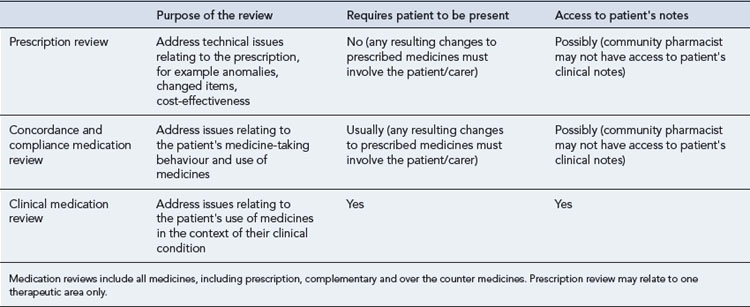

Prescribing a medicine is one of the most common interventions in health care used to treat patients. Medicines have the potential to save lives and improve the quality of life, but they also have the potential to cause harm, which can sometimes be catastrophic. Therefore, prescribing of medicines needs to be rational and effective in order to maximise benefit and minimise harm. This is best done using a systematic process that puts the patient at the heart of the process (Fig. 2.1).

Fig. 2.1 A framework for good prescribing

(from Background Briefing. A blueprint for safer prescribing 2009 © Reproduced by permission of the British Pharmacological Society.)

What is meant by rational and effective prescribing?

There is no universally agreed definition of good prescribing. The WHO promotes the rational use of medicines, which requires that patients receive medications appropriate to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their own individual requirements, for an adequate period of time, and at the lowest cost to them and their community. However, a more widely used framework for good prescribing has been described (Barber, 1995) and identifies what the prescriber should be trying to achieve, both at the time of prescribing and in monitoring treatment thereafter. The prescriber should have the following four aims:

Another popular framework to support rational prescribing decisions is known as STEPS (Preskorn, 1994). The STEPS model includes five criteria to consider when deciding on the choice of treatment:

Pharmacists as prescribers and the legal framework

Evolution of non-medical prescribing

Independent prescribing is defined as ‘prescribing by a practitioner (doctor, dentist, nurse, pharmacist) who is responsible and accountable for the assessment of patients with undiagnosed or diagnosed conditions and for decisions about the clinic management required including prescribing’ (DH, 2006).

In 1986, a report was published in the UK (‘Cumberlage report’) which recommended that community nurses should be given authority to prescribe a limited number of medicines as part of their role in patient care (Department of Health and Social Security, 1986). Up to this point, prescribing in the UK had been the sole domain of doctors, dentists and veterinarians. This was followed in 1989 by a further report (the first Crown report) which recommended that community nurses should prescribe from a limited formulary (DH, 1989). The legislation to permit this was passed in 1992.

At the end of the 1990s, in line with the then UK government’s desire to widen access to medicines by giving patients quicker access to medicines, improving access to service and making better use of the skills of health care professionals, the role of prescriber was proposed for other health care professionals. This change in prescribing to include non-medical prescribers (pharmacists, nurses and optometrists) was developed following a further review (Crown, 1999). This report suggested the introduction of supplementary prescribers, that is, non-medical health professionals who could prescribe after a diagnosis had been made and a clinical management plan drawn up for the patient by a doctor (Crown, 1999).

Supplementary prescribing

The Health and Social Care Act 2001 allowed pharmacists and other health care professionals to prescribe. Following this legislation, in 2003, the Department of Health outlined the implementation guide allowing pharmacists and nurses to qualify as supplementary prescribers (DH, 2003). In 2005, supplementary prescribing was extended to physiotherapists, chiropodists/podiatrists, radiographers and optometrists (DH, 2005).

Supplementary prescribing is defined as a voluntary prescribing partnership between an independent prescriber (doctor or dentist) and a supplementary prescriber (nurse, pharmacist, chiropodists/podiatrists, physiotherapists, radiographers and optometrists) to implement an agreed patient-specific clinical management plan with the patient’s agreement. This prescribing arrangement also requires information to be shared and recorded in a common patient file. In this form of prescribing the independent prescriber, that is the doctor or if appropriate the dentist, undertakes the initial assessment of the patient, determines the diagnosis and the initial treatment plan. The elements of this patient-specific plan, which are the responsibility of the supplementary prescriber, are then documented in the patient-specific clinical management plan. The legal requirements for which are detailed in Box 2.1. Supplementary prescribers can prescribe Controlled Drugs and also both off-label and unlicensed medicines.

Non-medical independent prescribing

Following publication of a report on the implementation of nurse and pharmacist independent prescribing within the NHS in England (DH, 2006), pharmacists were enabled to become independent prescribers as defined under the Medicines and Human Use (Prescribing; Miscellaneous Amendments) Order of May 2006. Pharmacist independent prescribers were able to prescribe any licensed medicine for any medical condition within their competence except Controlled Drugs and unlicensed medicines. The restriction on Controlled Drugs included those in Schedule 5 (CD Inv.POM and CD Inv.P) such as co-codamol. At the same time, nurses could also become qualified as independent prescribers (formerly known as Extended Formulary Nurse Prescribers) and prescribe any licensed medicine for any medical condition within their competence, including some Controlled Drugs. Since 2008, optometrists can also qualify as independent prescribers to prescribe for eye conditions and the surrounding tissue. They cannot prescribe for parenteral administration and they are unable to prescribe Controlled Drugs.

Following a change in legislation in 2010, pharmacist and nurse, non-medical prescribers, were allowed to prescribe unlicensed medicines (DH, 2010).

Accountability

If a prescriber is an employee then the employer expects the prescriber to work within the terms of his/her contract, competency and within the rules/policies, standard operating procedure and guidelines, etc. laid down by the organisation. Therefore, working as a prescriber, under these conditions, ensures that the employer has vicarious liability. So should any patient be harmed through the action of the prescriber and he/she is found in a civil court to be negligent, then under these circumstances the employer is responsible for any compensation to the patient. Therefore, it is important to always work within these frameworks, as working outside these requirements makes the prescriber personally liable for such compensation. To reinforce this message it has been stated that the job descriptions of non-medical prescribers should incorporate a clear statement that prescribing forms part of the duties of their post (DH, 2006).

Ethical framework

Four main ethical principles of biomedical ethics have been set out for use by health care staff in patient–practitioner relationships (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001). These principles are respect for autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, justice and veracity and need to be considered at all points in the prescribing process.

Autonomy

Gillick competence is used to determine if children have the capacity to make health care decisions for themselves. Children under 16 years of age can give consent as long as they can satisfy the prescriber that they have capacity to make this decision. However, with the child’s consent, it is a good practice to involve the parents in the decision-making process. In addition, children under 16 may have the capacity to make some decisions relating to their treatment, but not others. So it is important that an assessment of capacity is made related to each decision. There is some confusion regarding the naming of the test used to objectively assess legal capacity to consent to treatment in children under 16, with some organisations and individuals referring to Fraser guidance and others Gillick competence. Gillick competence is the principle used to assess the capacity of children under 16, while the Fraser guidance refers specifically to contraception (Wheeler, 2006).

The Mental Capacity Act (2005) protects the rights of adults who are unable to make decisions for themselves. The fundamental concepts within this act are the presumption that every adult has capability and should be supported to make their own individual decision. The five key principles are listed in Box 2.2. Therefore, any decision made on their behalf should be as unrestrictive as possible and must be in the patient’s own interest, not biased by any other individual or organisation’s benefit. Advice regarding patient consent is listed in Box 2.3.

Box 2.2 Overview of the five principles of the Mental Capacity Act

Beneficence

This is the principle of doing good and refers to the obligation to act for the benefit of others that is set out in codes of professional conduct, for example, pharmacists’ code of ethics and professional standards and guidance (Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009). Beneficence is referred to both physical and psychological benefits of actions and also related to acts of both commission and omission. Standards set for professionals by their regulatory bodies such as the General Pharmaceutical Council can be higher than those required by law. Therefore, in cases of negligence the standard applied is often that set by the relevant statutory body for its members.

Professional frameworks for prescribing

The professional standards for pharmacists are defined within ‘Medicines, Ethics and Practice’ and contain additional requirements for pharmacists who are qualified as non-medical prescribers and also good practice guidance (Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009). This guidance provides advice on a wide range of areas including self-audit, promotions, gifts from drug companies, written agreement with the employing organisation describing the prescriber’s scope of practice, liability and indemnity arrangements, competency to prescribe and not just prescribing and dispensing a medicine.

Off-label and unlicensed prescribing

The company which holds the marketing authorisation has the responsibility to compensate patients who are proven to have suffered unexpected harm caused by the medicine when prescribed and used in accordance with the marketing authorisation. Therefore, if a medicine is prescribed which is either unlicensed or off-label, the prescriber carries professional, clinical and legal responsibility and is therefore liable for any harm caused. Best practice on the use of unlicensed and off-label medicines is described in Box 2.4. In addition, all health care professionals have a responsibility to monitor the safety of medicines. Suspected adverse drug reactions should therefore be reported in accordance with the relevant reporting criteria.

Box 2.4 Advice for prescribing unlicensed and off-label medicines

(from Drug Safety Update, 2009; 2: 7, with kind permission from MHRA)

Consider

Communicate

Clinical governance

Clinical governance is described as having seven pillars:

Professional bodies have also incorporated clinical governance into their codes of practice. The four tenants of clinical governance are to ensure clear lines of responsibility and accountability; a comprehensive strategy for continuous quality improvement; policies and procedures for assessing and managing risks; procedures to identify and rectify poor performance in staff. Therefore, the professional bodies such as those of pharmacists, nurses and optometrists have also identified clinical governance frameworks for independent prescribing as part of their professional codes of conduct. The General Pharmaceutical Council, the UK pharmacy regulator, code of practice provided a framework not only for the individual pharmacist, non-medical prescriber, but also for their employing organisation. Suggested indicators for good practice are detailed in Box 2.5.

Box 2.5 Overview of clinical governance practice recommendations for prescribers

Competence and competency frameworks

The National Prescribing Centre has published a competency framework for pharmacist prescribers (Granby and Picton, 2006) which is described in Table 2.1. This framework is composed of three areas: the consultation, prescribing effectively and prescribing in context. These three areas are further subdivided to provide nine competencies each with an overarching statement. The nine competencies are:

Table 2.1 Overview of the National Prescribing Centre competency framework for pharmacists (Granby and Picton, 2006)

| Competency area | Competency | Behaviour indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Consultation | Clinical and pharmaceutical knowledge | 10 statements |

| For example, understands the conditions being treated, their natural progress and how to assess their severity | ||

| Establishing options | 14 statements | |

| For example, assesses the clinical condition using appropriate techniques and equipment | ||

| Communicating with patients | 11 statements | |

| For example, explains the nature of the patient’s condition, the rationale behind and potential risks and benefits of management options | ||

| Prescribing effectively | Prescribing safely | 9 statements |

| For example, only prescribes a medicine with adequate, up-to-date knowledge of its actions, indications, contraindications, interactions, cautions, dose and side effects | ||

| Prescribing professionally | 8 statements | |

| For example, accepts personal responsibility for own prescribing and understands the legal and ethical implications of doing so | ||

| Improving prescribing practice | 7 statements | |

| For example, reports prescribing errors and near misses, reviews practice to prevent recurrences | ||

| Prescribing in context | Information in context | 6 statements |

| For example, critically appraises the validity of information sources (e.g. promotional literature, research) | ||

| The NHS in context | 5 statements | |

| For example, follows relevant local and national guidance for medicines use (e.g. local formularies, care pathways, NICE guidance) | ||

| The team and individual context | 7 statements | |

| For example, establishes relationships with colleagues based on understanding, trust and respect for each other’s roles |

Each of these competencies is supported by a series of statements/behavioural indicators, all of which an individual needs to demonstrate they have achieved the overall competency (Table 2.1). Prescribers can review their prescribing performance using the nine competencies and the associated 77 behavioural indicators using this framework as a self-assessment tool. The framework is particularly useful when structuring ongoing CPD.

The prescribing process

Consultation

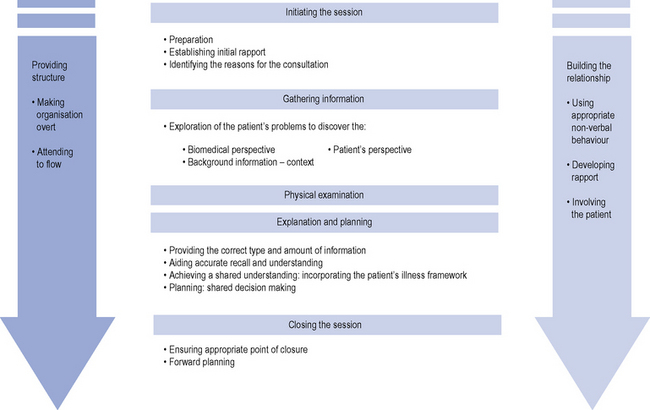

An example of this is the Calgary Cambridge framework which can be used to structure and guide patient consultations (Silverman et al., 2005). The framework is represented in Fig. 2.2. The five key stages of the consultation are:

Fig. 2.2 Calgary Cambridge consultation framework (Silverman et al., 2005).

Reproduced with kind permission from the Radcliffe Publishing Ltd, Oxford.

Building relationships

The prescribers also need to review their own non-verbal communication to ensure this reinforces the verbal message they are giving to the patient. For example, doctors who face the patient, make eye contact and maintain an open posture were regarded by their patients to be more interested and empathic (Harrigan et al., 1985). Also health care professionals in primary care who demonstrated non-verbal intimacy (close distance, leaning forward, appropriate body orientation and touch) had increased patient satisfaction (Larsen and Smith, 1981).

Initiating the session

During the first stage of the consultation the prescriber needs to greet the patient and confirm his/her identity. They should also ensure the environment for the consultation is appropriate for maintaining eye contact and ensuring confidentiality. The prescriber should also introduce him/herself, his/her role and gain relevant consent. During this stage the prescriber must demonstrate respect for the patient and establish a patient-centred focus. Using initially open and then closed questions the prescriber needs to identify the patient’s problem/issues. By adopting this approach and actively listening, the prescriber is able to confirm the reason for the consultation and identify other issues. This allows the prescriber to negotiate an agenda for the next stages of the consultation through agreement with the patient and taking into account both the patient and prescriber’s needs. This initial stage is vital for the success of the consultation as many patients have hidden agendas which, if not identified at this stage, can lead to these concerns not being addressed. Beckman and Frankel (1984) studied doctors’ listening skills and identified that even minimal interruptions by doctors to initial patients’ statements at the beginning of the consultation prevented patients’ concerns from being expressed. This resulted in either these issues not being identified at all or they were raised by patient’s late in the consultation

Gathering information

The aim of this stage is to explore the problem identified from both the patient and prescriber’s perspective to gain background information which is both accurate and complete. Britten et al. (2000) identified that lack of patient participation in the consultation led to 14 categories of misunderstanding between the prescriber and patient. These included patient information unknown to the prescriber, conflicting information from the patient and communication failure with regard to the prescriber’s decision. During this stage the illness framework, identified by exploring the patient’s ideas, concerns, expectations and experience of his/her condition and effect on his/her life, is combined with the information gained by the prescriber through his/her biomedical perspective. This encompasses signs, symptoms, investigations and underlying pathology. Assimilation of this information leads the prescriber to a differential diagnosis. By incorporating information from both viewpoints, a comprehensive history detailing the sequence of events can be obtained using questioning, listening and clarification. This ends with an initial summary where the prescriber invites the patient to comment and contribute to the information gathered.

Explanation and planning

In one UK study, doctors were found to overestimate the extent to which they completed the tasks of discussing the risk of medication, checking the ability of the patient to follow the treatment plan and obtaining the patient’s input and view on the medication prescribed (Makoul et al., 1995).

In order to successfully accomplish this stage of the consultation, the prescriber needs to use a number of skills and also to involve the patient. The prescriber should ensure he/she gives the correct type and amount of information. This is done by assessing the patient’s prior knowledge by employing both open and closed questions. By organising the information given into chunks which can be easily assimilated the prescriber can then check the patient understands the information given. Questioning the patient regarding additional information they require also helps to ensure the patient’s involvement and maintains rapport. The prescriber must determine the appropriate time to give explanations and also allow the patient time to consider the information provided. Signposting can also be a useful technique to employ during this stage. Once again the language used should be concise, easy to understand and avoid jargon. Using diagrams, models and written information can enhance and reinforce patient understanding. The explanation should be organised into discreet sections with a logical sequence so that important information can be repeated and summarised. Box 2.6 summarises the issues the prescriber should consider before prescribing a medicine.

Communicating risks and benefits of treatment

Communicating risk is not simple (Paling, 2003). Many different dimensions and inherent uncertainties need to be taken into account, and patients’ assessment of risk is primarily determined by emotions, beliefs and values, not facts. This is important, because patients and health care professionals may ascribe different values to the same level of risk. Health care professionals need to be able to discuss risks and benefits with patients in a context that would enable the patient to have the best chance of understanding those risks. It is also prudent to inform the patient that virtually all treatments are associated with some harm and that there is almost always a trade-off between benefit and harm. How health care professionals present risk and benefit can affect the patient’s perception of risk.

Some important principles to follow when describing risks and benefit to patients:

Visual patient decision aids are becoming increasingly popular as a tool that health care professionals can use to support discussions with patients by increasing their knowledge about expected outcomes and helping them to relate these to their personal values (National Prescribing Centre, 2008). Further information about using patient decision aids can be found at http://www.npci.org.uk/therapeutics/mastery/mast4/patient_decision_aids/patient_decision_aid1.php

Adherence

Adherence has been defined as the extent to which a patient’s behaviour matches the agreed recommendation from the prescriber. When a patient is non-adherent this can be classified as intentional or unintentional non-adherence (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009).

Unintentional non-adherence occurs when the patient wishes to follow the treatment plan agreed with the prescriber, but is unable to do so because of circumstances beyond their control. Examples of this include forgetting to take the medicine at the defined time or an inability to use the device prescribed. Strategies to overcome such obstacles include medication reminder charts, use of multi-compartment medication dose systems, large print for those with poor eyesight, aids to improve medication delivery, for example inhaler-aids, tube squeezers for ointments and creams, and eye drop administration devices. A selection of these devices is detailed in a guide to the design of dispensed medicines (National Patient Safety Agency, 2007).

Studies have demonstrated that between 35% and 50% of medicines prescribed for chronic conditions are not taken as recommended (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009). Therefore, it is the prescriber’s responsibility to explore with the patient their perceptions of medicines to determine if there are any reasons why they may not want to or are unable to use the medicine. In addition, any barriers which might prevent the patient from using the treatment as agreed, for example manual dexterity, eyesight, memory, should be discussed and assessed. Such a frank discussion should enable the patient and prescriber to jointly identify the optimum treatment regimen to treat the condition. In addition, information from the patient’s medical records can be used to assess adherence. For example, does the frequency of requests for repeat medication equate to the anticipated duration of use?

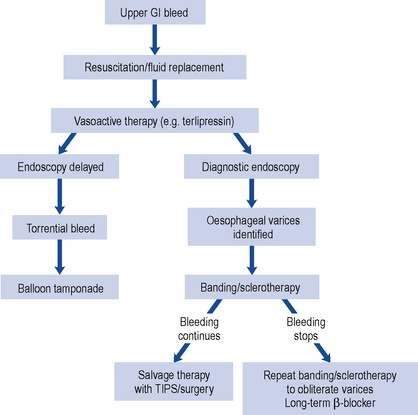

Medication review

Medication review has been defined as ‘a structured, critical examination of a patient’s medicines with the objective of reaching an agreement with the patient about treatment, optimising the impact of medicines, minimising the number of medication-related problems and reducing waste’ (Medicines Partnership, 2002).

The benefits of medication review are now being recognised by health policy makers, and in the UK, community pharmacists are required to carry out different levels of medication review as part of their normal clinical activities. Medication reviews are often targeted towards patient groups who are more likely to have problems with their medicines, for example the elderly, patients taking more than four medicines regularly, patients in care homes, those on medicines with special monitoring requirements. Characteristics of different types of medication review are described in Table 2.2.

The key elements of an advanced clinical medication review are:

The NO TEARS approach (Lewis, 2004) is also a useful prompt to assist such a review (Table 2.3).

| NO TEARS | Questions to think about |

|---|---|

| Need and indication | Why is the patient taking the medicine, and is the indication clearly documented in the notes? |

| Do they still need the medicine? | |

| Is the dose appropriate? | |

| Has the diagnosis been confirmed or refuted? | |

| Would a non-drug treatment be better? | |

| Does the patient know what their medicines are for? | |

| Open questions | Use open questions to find out what the patient understands about their medicines, and what problems they may be having with them. |

| Tests and monitoring | Is the illness under control? |

| Does treatment need to be adjusted to improve control? | |

| What special monitoring requirements are there for this patient’s medicines? | |

| Who is responsible for checking test results? | |

| Evidence and guidelines | Is there new evidence or guidelines that mean I need to review the patient’s medicines? |

| Is the dose still appropriate? | |

| Do I need to do any other investigations or tests? | |

| Adverse effects | Does the patient have any side effects? |

| Are any of the patient’s symptoms likely to be caused by side effects of medicines, including OTC and complementary medicines? | |

| Are any of the patients’ medicines being used to treat side effects of other medicines? | |

| Is there any new advice or warnings on side effects or interactions? | |

| Risk reduction and prevention | If there is time, ask about alcohol use, smoking, obesity, falls risk or family history, for opportunistic screening. |

| Is treatment optimised to reduce risks? | |

| Simplification and switches | Can the patient’s medicines regimen be simplified? |

| Are repeat medicines synchronised for prescribing at the same time? | |

| Explain any changes in medicines to the patient. |

Factors that influence prescribers

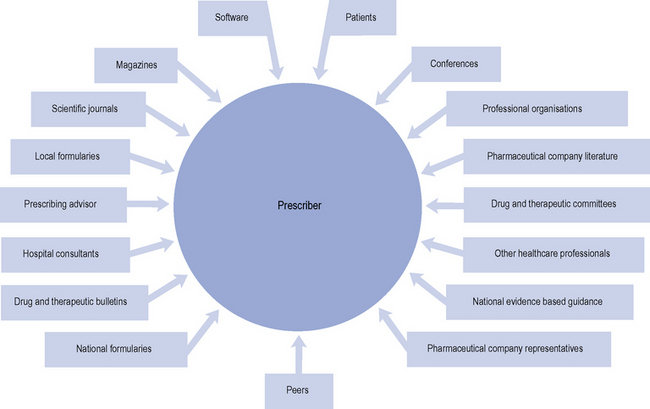

A range of influences that affect the prescribing decisions made by primary care doctors have been identified (Fig. 2.3).

Patients and prescribing decisions

The informed patient

Health care is moving to a position of greater shared decision making with patients and development of the concept of patient autonomy. This is being supported through the better provision of information for patients about their prescribed medicines. The EU directive 2001/83 (European Commission, 2001) requires that all pharmaceutical products are packaged with an approved PIL, which provides information on how to take the medicine and possible adverse effects. Other important developments that have increased patients’ access to information, albeit of variable quality, include the role of the media in general and the amount of attention they give to health and health-related matters, the emergence of the Internet, and the development of patient support groups. The reporting in the media of concerns regarding the safety of MMR vaccine and the subsequent rapid drop in MMR vaccinations rates in children is a good example of the importance of these developments in influencing patients and prescribing.

Health care policy

National policy and guidelines, for example National Service Frameworks and guidance from NICE in the UK, have a significant influence on prescribing, although the influence may not be as great as expected for some medicines (Prescribing Support Unit, 2009).

Colleagues

Several studies have found that health care professionals in primary care (both doctors and nurses) rely on advice from trusted colleagues and opinion leaders as a key source of information on how to manage patients. It has been estimated that 40% of prescribing in primary care was strongly influenced by hospitals because the choice of medicine prescribed in general practice was often guided by hospital specialists through their precedent prescribing and educational advice (National Audit Office, 2007). The Pharmaceutical Industry recognise the value of identifying ‘key opinion’ leaders amongst the medical community and will try to cultivate them to influence their peers and fellow clinicians, by paying them for a consultancy, lecture fees, travel, research and articles favourable to that company’s products.

Pharmaceutical industry

The pharmaceutical industry has a very wide and important influence on prescribing decisions affecting every level of health care provision, from the medicines that are initially discovered and developed through clinical trials, to the promotion of medicines to the prescriber and patient groups, the prescription of medicines and the compilation of clinical guidelines. There are over 8000 pharmaceutical company representatives in the UK trying to persuade prescribers to prescribe their company’s product. This represents a ratio of about 1 representative for every 7.5 doctors (House of Commons Health Committee, 2005) with 1 representative for every 4 primary care doctors (National Audit Office, 2007). Whilst representatives from the pharmaceutical industry can provide useful and important new information to prescribers about medicines, the information presented is not without bias and rarely provides any objective discussion of available competitor products.

Cognitive factors

Most prescribing decisions are made using the processes our brains develop to handle large volumes of complex information quickly. This rapid decision making is aided by heuristics, strategies that provide shortcuts that allow us to make quick decisions. This type of decision making largely relies on a small number of variables that we believe are important based on information collected by brief reading in summary journals (e.g. Bandolier, Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin and articles in popular doctors’ and nurses’ magazines mailed free of charge) and talking to colleagues. However, it is important to recognise that cognitive biases affect these heuristics (or shortcuts) involved in rapid decision making, and that experts as well as generalists are just as fallible to cognitive biases in decision making. At least 43 cognitive biases in decision making have been described. Some examples of cognitive biases that may affect prescribing decisions are shown in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4 Examples of types of cognitive biases that influence prescribing

| Type of cognitive bias | Description |

|---|---|

| Novelty preference | The belief that the progress of science always results in improvements and that newer treatments are generally better than older treatments |

| Over optimism bias | Tendency of people to over-estimate the outcome of actions, events or personal attributes to a positive skew |

| Confirmation bias | Information that confirms one’s already firmly held belief is given higher weight than refuting evidence |

| Mere exposure effect | More familiar ideas or objects are preferred or given greater weight in decision making |

| Loss aversion | To weigh the avoidance of loss more greatly than the pursuit of an equivalent gain |

| Illusory correlation | The tendency to perceive two events as causally related, when in fact the connection between them is coincidental or even non-existent |

Strategies to influence prescribing

Managerial approaches to influence prescribing

Local and national guidelines

Guidelines for the use of a medicine, a group of medicines or the management of a clinical condition may be produced for local or national use. They can be useful tools to guide and support prescribers in choosing which medicines they should prescribe. Ideally, guidelines should make evidence-based standards of care explicit and accessible, and aid clinical decision making. The best-quality guidelines are usually those produced using systematically developed evidence-based statements to assist clinicians in making decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances. In the UK, there is an accreditation scheme to recognise organisations who achieve high standards in producing health or social care guidance. Examples of accredited guidelines are those produced by NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, www.nice.org.uk) and SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network, www.sign.ac.uk). Local guidelines are often developed to provide a local context and interpretation of national guidance, and offer guidance on managing patients between primary and secondary care. However, despite the availability of good quality accessible clinical guidelines, implementation in practice remains variable.

Clinical decision support systems are increasingly popular as a way of improving clinical practice, and influence prescribing. These often utilise interactive computer programs that help clinicians with decision-making tasks at the point of care, and also help them keep up-to-date, and support implementation of clinical guidelines. Clinical knowledge summaries (www.cks.nhs.uk) is a decision support system developed for use in primary care that includes PILs, helps with differential diagnosis, suggests investigations and referral criteria, and gives screens that can be shared between the patient and the prescriber in the surgery.

Support and education

In order to change prescribing practice, pharmacists need to be aware of how to use an adoption model-based approach to convey key messages to the prescriber to help them change practice. One such model is known as AIDA (see Table 2.5)

| Awareness | Make the prescriber aware of the issues, prescribing data and evidence for the need to change |

| Interest | Let the prescriber ask questions and find out more about the proposed change: what the benefits are, what the prescriber’s concerns are |

| Decision | Help the prescriber come to a decision to make a change. How can the change be applied to their patients, what support is there to overcome the barriers to change, provide further information and training to support the change |

| Action | Action of making a change by the prescriber. Support this with simple reminders, patient decision support, feedback data and audit |

Audit Commission. Primary Care Prescribing – A Bulletin for Primary Care Trusts. London: Audit Commission, 2003.

Barber N. What constitutes good prescribing? Br. Med. J.. 1995;310:923-925.

Beauchamp T.L., Childress J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, fifth ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Beckman H.B., Frankel R.M. The use of videotape in internal medicine training. J. Gen. Intern. Med.. 1984;9:517-521.

Britten N., Stevenson F.A., Barry C.A., Barber N., Bradley C.P. Misunderstandings in prescribing decision in general practice: qualitative study. Br. Med. J.. 2000;320:484-488.

Clyne W., Blenkinsopp A., Seal R. A Guide to Medication Review. Liverpool: National Prescribing Centre, 2008.

Crown J. Review of Prescribing, Supply and Administration of Medicines. London: Department of Health, 1999. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4077153.pdf

Department of Health and Social Security. Neighbourhood Nursing. A Focus for Care. In Report of the community nursing review. London: HMSO; 1986.

De Vries T.P.G.M., Henning R.H., Hogerzeil H.G., et al. Guide to Good Prescribing – A Practical Manual. Geneva: WHO, 1994.

DH. Review of Prescribing, Supply and Administration of Medicines (The Crown Report). London: Department of Health, 1989.

DH. Supplementary Prescribing by Nurses and Pharmacists with the NHS in England: A Guide for Implementation. London: Department of Health, 2003. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4068431.pdf

DH. Supplementary Prescribing by Nurses, Pharmacists, Chiropodists/Podiatrists, Physiotherapists and Radiographers Within the NHS in England: A Guide for Implementation. London: Department of Health, 2005. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4110032

DH. Improving Patients’ Access to Medicines. In A Guide to Implementing Nurse and Pharmacist Independent Prescribing Within the NHS in England. London: Department of Health; 2006. Available online at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/ dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4133747.pdf

DH. Reference Guide to Consent for Examination or Treatment, second ed. London: Department of Health, 2009. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_103653.pdf

DH. Changes to Medicines Legislation to Enable Mixing of Medicines Prior to Administration in Clinical Practice. London: Department of Health, 2010. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Medicinespharmacyandindustry/Prescriptions/ TheNon-MedicalPrescribingProgramme/DH_110765

European Commission. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community Code Relating to Medicinal Products for Human Use. Available at: http://pharmacos.eudra.org/F2/review/doc/finaltext/011126-COM_2001_404-EN.pdf, 2001.

Granby T., Picton C. Maintaining Competency in Prescribing. An Outline Framework to Help Pharmacists Prescribers. Available at: http://www.npc.co.uk/prescribers/resources/competency_framework_oct_2006.pdf, 2006.

Greenhalgh T., Macfarlane F., Maskrey N. Getting a better grip on research: the organisational dimension. InnovAiT. 2010;3:102-107.

Harrigan J.A., Oxman T.E., Rosenthal R. Rapport expressed through non-verbal behavior. J. Nonverbal. Behav.. 1985;9:95-110.

House of Commons Health Committee. The Influence of the Pharmaceutical Industry HC 42-I. London: The Stationery Office, 2005.

Larsen K.M., Smith C.K. Assessment of non-verbal communication in patient-physician interview. J. Fam. Pract.. 1981;12:481-488.

Lewis T. Using the NO TEARS tool for medication review. Br. Med. J.. 2004;329:434.

Makhinson M. Biases in medication prescribing: the case of second-generation antipsychotics. J. Psychiatr. Pract.. 2010;16:15-21.

Makoul G., Arnston P., Scofield T. Health promotion in primary care physician-patient communication and decision about prescription medicines. Soc. Sci. Med.. 1995;41:1241-1254.

Medicines Partnership. Room for Review. A Guide to Medication Review: The Agenda for Patients, Practitioners and Managers. London: Medicines Partnership; 2002.

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Off-label use or unlicensed medicines: prescribers’ responsibilities. Drug Safety Update. 2009;2:7.

Mossialos E., Mrazek M., Walley T. Regulating Pharmaceuticals in Europe: Striving for Efficiency. In Equity and Quality. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2004.

National Audit Office. Prescribing Costs in Primary Care. London: The Stationery Office, 2007.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Medicines Adherence Involving Patients Indecisions About Prescribed Medicines and Supporting Adherence. Clinical Guideline 76. London: NICE, 2009. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11766/43042/43042.pdf

National Patient Safety Agency. Design for Patient Safety: A Guide to the Design of Dispensed Medicines. London: NPSA, 2007.

National Prescribing Centre. Prescribing New Drugs in General Practice. MeReC Bulletin. 1998;9:21-24.

National Prescribing Centre. Using Patient Decision Aids. MeReC Extra No. 36. Available at http://www.npc.co.uk/ebt/merec/other_non_clinical/resources/merec_extra_no36.pdf, 2008.

Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. Br. Med. J.. 2003;327:745-748.

Prescribing Support Unit. Use of NICE Appraised Medicines in the NHS in England – Experimental Statistics. The Health and Social Care Information Centre, Prescribing Support and Primary Care. Available at: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/niceappmed/Use%20of%20NICE%20appraised%20medicines%20in%20the%20NHS%20in%20England.pdf, 2009.

Preskorn S.H. Antidepressant drug selection: criteria and options. J. Clin. Psychiatr.. 1994;55(Suppl A):6-22. discussion 23–4, 98–100

Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Clinical Governance Framework for Pharmacist Prescribers and Organisations Commissioning or Participating in Pharmacy Prescribing. London: RPSGB, 2007.

Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Medicines Ethics and Practice: A Guide for Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians. London: RPSGB, 2009.

Silverman J., Kurtz S., Draper J. Skills for Communicating with Patients, second ed. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2005.

Wheeler R. Gillick or Fraser? A plea for consistency over competence in children. Br. Med. J.. 2006;332:807.

Appelbe G.E., Wingfield J. Dale and Appelbe’s Pharmacy Law and Ethics, ninth ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2009.

Horne R., Weinman J., Barber N., et al. Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine taking. London: Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D, 2005. Available at: http://www.sdo.nihr.ac.uk/files/project/76-final-report.pdf

NHS Litigation Authority. Clinical Negligence. In A Very Brief Guide for Clinicians. London: NHS Litigation Authority; 2003.