11 Prepregnancy counselling, prenatal diagnosis and antenatal care

Prepregnancy counselling

General advice

Prenatal diagnosis

Screening tests

Combined tests

Some tests use both NT and biochemical markers to calculate a risk of Down’s syndrome.

Limits of screening tests

Ultrasound in pregnancy

First trimester (10–14 weeks)

• Establish viability: some pregnancies have failed by the time of the first-trimester scan and the diagnosis of missed miscarriage is made if crown–rump length >7 mm with no fetal heart detected. These women should be offered counselling and evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC).

• Confirm gestation: up to 14 weeks, the estimated due date should be amended if there is more than 7 days’ discrepancy between dates by last menstrual period and by crown–rump length at scan. Beyond 14 weeks, the gestation should be estimated by biparietal diameter or head circumference, and estimated due date corrected if there is more than 14 days’ discrepancy with menstrual dates. Correct dating is very important for planning induction if the woman does not go into spontaneous labour, but dating of pregnancy becomes less accurate with increasing gestation.

• Gross anatomy: major anomalies such as anencephaly, cystic hygroma, bladder outflow obstruction and major anterior abdominal wall defects can be detected at first-trimester scan.

• Multiple pregnancies: multiple pregnancies can be detected and chorionicity and amnionicity are most reliably determined in the first trimester.

Second trimester (18–24 weeks)

• Structural anatomy: the whole fetus should be examined (brain, face, heart, kidneys, abdomen, spine, hands and feet, genitalia, bladder) and referral made to a fetal medicine unit if any abnormalities are detected.

• Fetal growth: very rarely, often associated with pre-eclampsia, early-onset intrauterine growth restriction or oligohydramnios is detected at the second-trimester scan and indicates further follow-up in the fetal medicine department and close monitoring for pre-eclampsia.

• Fetal sex: this can be determined in the second trimester with 99% accuracy if parents wish it, though concerns over the misuse of this information by some cultural groups means that it is not offered in all units.

• Placental site: if the placenta encroaches into the lower segment of the uterus a further scan is arranged for 34 weeks to recheck its location and plan delivery accordingly.

Antenatal care

Most women will not need to see an obstetrician unless factors in the booking or during the antenatal period indicate. Indications for referral at booking are shown in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Factors at booking indicating referral for obstetric or senior midwifery review

| Age over 40 years or under 19 years |

| Body mass index ≥35 or <18 |

| Grand multiparity (more than six pregnancies) |

| Conditions such as hypertension, cardiac or renal disease, endocrine, psychiatric or haematological disorders, epilepsy, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, cancer, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) |

| Previous caesarean section or other uterine surgery |

| Previous postpartum haemorrhage |

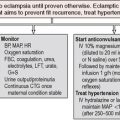

| Severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia |

| Previous pre-eclampsia or eclampsia |

| Three or more miscarriages |

| Previous preterm birth or mid-trimester loss |

| Previous psychiatric illness or puerperal psychosis |

| Previous neonatal death or stillbirth |

| Previous baby with congenital abnormality |

| Previous small for gestational age (SGA) or large for gestational age (LGA) infant |

| Family history of genetic disorder |

Booking (6–12 weeks)

Booking blood tests

• Full blood count: to exclude anaemia.

• Group and antibody check: to detect Rhesus-negative women and atypical antibodies.

• Haemoglobinopathy screen: this may be checked in all women or used selectively for those of Afro-Caribbean, Mediterranean or Asian origin. Those with positive results should be offered counselling and partner testing followed by antenatal diagnosis for at-risk fetuses.

• Rubella: to check immunity and plan postnatal vaccination for those with low-level or no immunity. Such women must also be warned about avoiding exposure to the virus.

• Syphilis: to check for syphilis antibodies, which indicate a possibility of current infection in the mother and therefore risk of congenital abnormality in the fetus. Women with a positive result must be referred to a genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinic, though many will be false positives from pregnancy or previously treated disease.

• Hepatitis B: women with positive results should be referred to a gastroenterologist. Neonatal vaccination and immunoglobulin must be planned and interventions such as fetal scalp electrode and fetal blood sampling in labour should be avoided.

• HIV: HIV-positive women should be referred to GUM physicians, offered counselling and given antiviral agents prior to delivery. They should be advised to deliver by caesarean section and avoid breastfeeding.

Rhesus disease and other red-cell alloimmune antibodies

• Threatened miscarriage, miscarriage, ERPC or ectopic pregnancy

• Trauma to the abdomen, such as amniocentesis, CVS or road traffic accident

• Abruption or other antepartum haemorrhage

• Delivery, especially if multiple pregnancy or manual removal of placenta

Summary

• Prepregnancy counselling is vital for those with serious medical conditions such as diabetes, epilepsy and cardiac or renal disease to minimize the likely impact of pregnancy on the disease and of the disease (or medication) on the pregnancy.

• Women with high-risk cardiac disease or severe renal disease should be advised not to become pregnant.

• Antenatal screening for Down’s syndrome should be offered early to all pregnant women, with clear counselling regarding screening versus diagnostic tests. The screening tests are also useful in predicting other abnormalities such as cardiac disease.

• Ultrasound in the first trimester will confirm gestation and viability, check for major abnormalities and determine chorionicity in multiple pregnancy.

• Second-trimester ultrasound will check the detailed anatomy of the baby, but also confirm the placental site and growth of the baby.

• Rhesus status must be checked at booking to ensure that Rhesus-negative women are given anti-D either routinely at 28 weeks, 34 weeks and delivery, or after sensitizing events.

• Other important antibodies in haemolytic disease of the newborn are anti-c and anti-K.

• Most women will have normal pregnancies and do not need to see an obstetrician antenatally, but those with obstetric or medical problems must have their care tailored accordingly, often within a multidisciplinary team.