Preparation of the Patient

Preoperative Consultation

The average number of surgical procedures and length of time required to complete all stages of the reconstruction are discussed with the patient (Table 5-1). In cases of repair of the nose, when an interpolated covering flap is planned, the reconstructive sequence includes initial flap transfer, pedicle division 3 weeks later, a contouring procedure 2 or 3 months after pedicle division, and possibly dermabrasion in the office 2 months after contouring of the flap. We therefore advise patients that up to 6 months may be necessary for the restoration to be completed.

TABLE 5-1

Estimated Number of Surgical Procedures and Recovery Periods

| Type of Procedure | Number of Procedures | Initial Recovery |

| Local flap | 1-2 | 1-2 weeks |

| Skin graft | 2 | 1-2 weeks |

| Interpolated flap | 2-4 | 4 weeks |

From Naficy S: Preparation of the patient. In Baker SR, editor: Principles of nasal reconstruction, 2nd ed, New York, Springer, 2011.

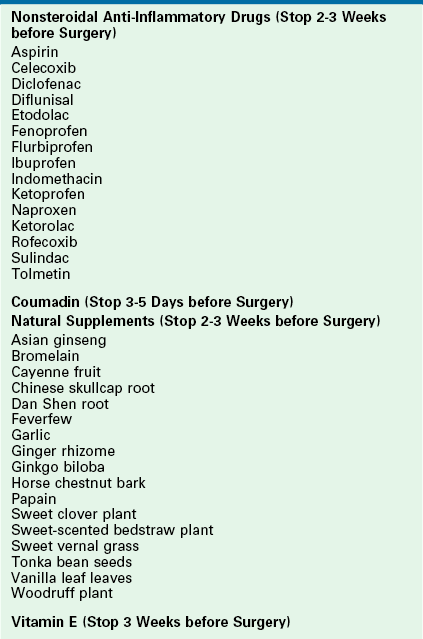

Preoperative consultation with the patient is ideally scheduled 4 to 6 weeks before surgery, allowing adequate time for the patient to stop anticoagulant agents. Medications to be avoided beginning up to 3 weeks before surgery include all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and vitamin E supplements (Table 5-2). Coumadin should be discontinued 3 to 5 days before surgery. A number of herbal supplements also possess anticoagulant properties and should be avoided.

TABLE 5-2

List of Medications to Avoid Before Surgery

From Naficy S: Preparation of the patient. In Baker SR, editor: Principles of nasal reconstruction, 2nd ed, New York, Springer, 2011.

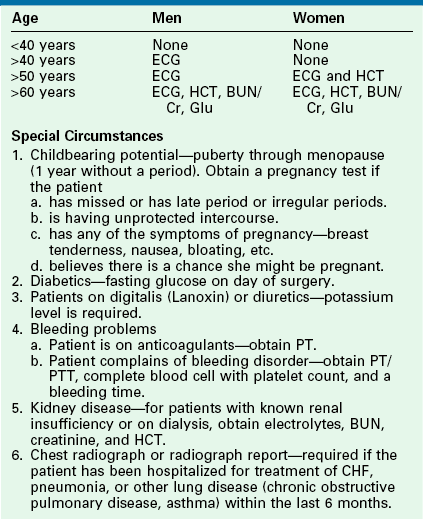

A medical history is obtained from the patient, and a physical examination is performed as part of the consultation. The general health of the patient is noted, with special attention given to hypertension, symptomatic coronary artery disease, and smoking history. Smokers are strongly encouraged to quit and are instructed on the higher risk of complications for users of tobacco products. An electrocardiogram is obtained for all men older than 40 years and women older than 50 years. All patients older than 60 years are tested for hematocrit and blood levels of urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glucose (Table 5-3). During the physical examination, note is made of prior facial cutaneous surgery or ear surgery involving the cartilage. The patient is examined for scars on the face that may potentially influence the design of flaps. The redundancy of the facial skin is assessed, particularly in the area of the anticipated cutaneous defect. The position of the anterior hairline is noted when a paramedian forehead flap for nasal reconstruction is anticipated. Patients with low hairlines are informed about the possibility of the flap’s extending to hair-bearing scalp and the need for subsequent depilation procedures on the nose.

TABLE 5-3

From Naficy S: Preparation of the patient. In Baker SR, editor: Principles of nasal reconstruction, 2nd ed, New York, Springer, 2011.

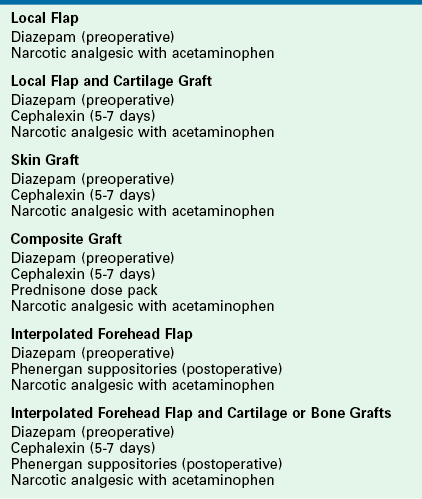

We provide patients with prescriptions for medications at the time of preoperative consultation (Table 5-4). Oral diazepam (5 to 10 mg) is prescribed for patients younger than 70 years with instructions to take it the evening before and 1 hour before the operation. Benzodiazepines help reduce preoperative anxiety and counteract the toxic effects of local anesthetics used during the procedure. In instances in which skin or composite grafting is planned or cartilage and bone grafting is anticipated, patients are given a postoperative course of an oral antistaphylococcal antibiotic for 5 to 7 days. A tapering dose pack of prednisone is prescribed for those patients undergoing composite grafting. An analgesic of choice is prescribed in appropriate quantity. In addition to the standard medications, those patients requiring a forehead flap are prescribed a 2-day supply of antiemetic suppositories.

TABLE 5-4

From Naficy S: Preparation of the patient. In Baker SR, editor: Principles of nasal reconstruction, 2nd ed, New York, Springer, 2011.

Photography

The senior author’s technique for photography has been consistent during the past 12 years. Most photographs in the chapters he has authored in this book were obtained by the following setup. For in-office photographs, the system uses two Canon EOS Digital Rebel XT camera bodies, each outfitted with Canon zoom 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 lenses. Two ceiling-mounted strobe flashes are aimed at an angle of 25° to 30°, 6 feet from the subject. The strobe flashes are hard-wired to the camera bodies for synchronization. A backlight illuminates a blue background to eliminate shadow. Blue is chosen as the background color as it provides an excellent contrast to the color of flesh and hair.

Anesthesia

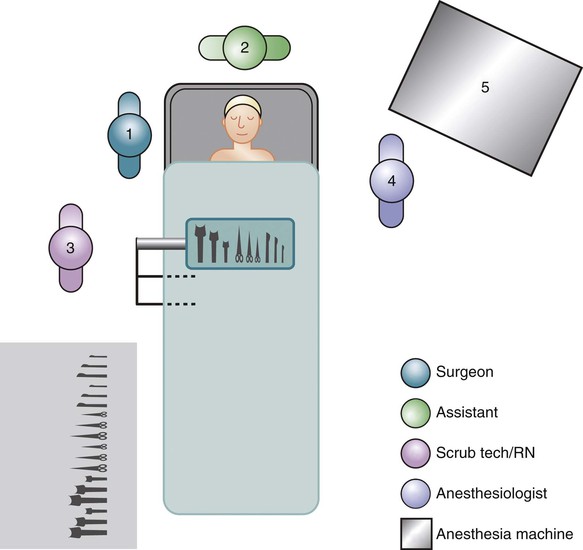

Monitored anesthesia care is appropriate for the majority of facial reconstructive procedures, including all skin grafts, local or regional flaps, and cartilage grafts. The patient is placed on a head/neck surgery stretcher with the head of the stretcher turned 90° to 120° from the anesthetist but near enough to the anesthetist to allow manipulation of the airway if necessary (Fig. 5-1). The patient is positioned supine without a special headrest. A doughnut-shaped foam pillow is placed under the patient’s head, and a towel roll supports the shoulders. A standard-sized pillow is placed under the knees to provide flexion and to reduce back strain. The stretcher is placed in an appropriate degree of reverse Trendelenburg’s position to reduce venous pooling in the face. Oxygen is administered at the rate of 2 to 4 L/min by nasal cannula tubing either nasally or orally. Preoxygenation reduces the toxic effects of local anesthetics and accommodates brief periods of apnea caused by intravenous sedation. To prevent the risk of fire, it is important to reduce or to stop the flow of oxygen when cautery is performed in the area of the nasal cannula openings.

FIGURE 5-1 Operating room setup for facial reconstruction using monitored anesthesia care. (From Naficy S: Preparation of the patient. In Baker SR, editor: Principles of nasal reconstruction, 2nd ed, New York, Springer, 2011.)

After adequate oxygenation, the patient is given a bolus of intravenous sedatives and narcotics, achieving an adequate depth of anesthesia to enable the surgeon to infiltrate the local anesthetic. It is not uncommon for the patient to require a chin thrust at this point to prevent transient apnea. After infiltration of the local anesthetic, the patient is maintained at an appropriate level of intravenous sedation for the duration of the procedure.

Local Anesthesia

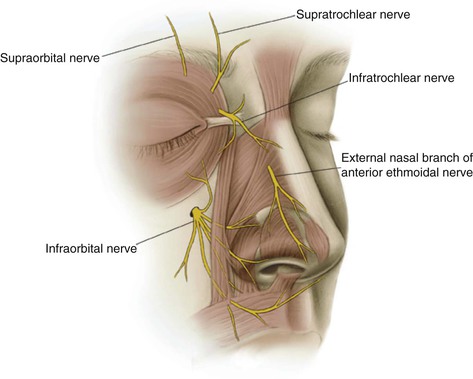

It may be useful to perform nerve blocks before local infiltration of the face (Fig. 5-2). An anesthetic block of the midface can be obtained by infiltrating the infraorbital (V2) nerve as it exits the maxilla. The nerve exits the infraorbital foramen 1 cm below the level of the inferior orbital rim, vertically aligned with the pupil. The nerve is blocked by injecting 1 mL of lidocaine (1% with 1 : 100,000 concentration of epinephrine) just above the periosteum around the site of exit of the nerve from the foramen. The injection may be performed percutaneously with a 30-gauge needle or through the gingivobuccal sulcus with a 27-gauge needle. The external nasal branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve supplies the skin of the caudal half of the nasal dorsum and most of the tip. This nerve is blocked by injection of anesthetic in the subfascial plane of the nasal sidewall at the junction of nasal bone and upper lateral cartilage approximately 1 cm lateral to the midline. The infratrochlear nerve supplies the skin of the upper nasal vault. This nerve is blocked by infiltration of anesthetic under the thin skin of the lateral bony nasal sidewall, medial to the medial canthus. Bilateral blocks of all of the nerves discussed will result in anesthesia of the majority of the skin and soft tissue of the nose, medial cheek, and upper lip. The forehead can be anesthetized by a nerve block of the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves. The supraorbital nerve exits its foramen and extends superiorly toward the scalp in a line that is directly vertical to the pupil. The supratrochlear nerve ascends toward the scalp in a line that is a vertical tangent to the medial limits of the eyebrow. This line is 1.5 cm lateral to the midline. The skin of the lower lip and chin can be anesthetized by blocking the mental nerve. This nerve exits the mental foramen, which is located at the midpupillary line.

Postoperative Care

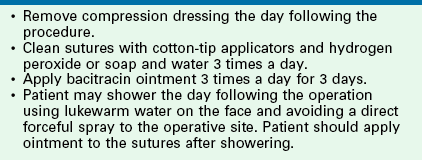

Written postoperative instructions that cover general wound care (Table 5-5) are provided. Patients are provided with an adequate supply of cotton-tipped applicators, hydrogen peroxide, and antibiotic ointment. Patients are instructed to avoid heavy lifting, bending, straining, and nose blowing if nasal reconstruction has been performed. There are other postoperative instructions specific to each procedure.

TABLE 5-5

General Wound Care Instructions

From Naficy S: Preparation of the patient. In Baker SR, editor: Principles of nasal reconstruction, 2nd ed, New York, Springer, 2011.

× 3-inch surgical cottonoids moistened with an equal mixture of topical lidocaine 4% and oxymetazoline hydrochloride are used to apply the mixture to nasal mucosa. The topical medicine is left in contact with the nasal mucosa for a few minutes before injection of the mucosa with local anesthetic. The septum is injected in the subperichondrial plane with a 27-gauge needle and a 3-mL syringe for adequate hydraulic force.

× 3-inch surgical cottonoids moistened with an equal mixture of topical lidocaine 4% and oxymetazoline hydrochloride are used to apply the mixture to nasal mucosa. The topical medicine is left in contact with the nasal mucosa for a few minutes before injection of the mucosa with local anesthetic. The septum is injected in the subperichondrial plane with a 27-gauge needle and a 3-mL syringe for adequate hydraulic force.