CHAPTER 2 Preparation for endoscopy

2.1 Management of patients on antithrombotic therapy prior to gastrointestinal endoscopy

Key Points

1 Procedure-related bleeding

Procedure risk may be classified as below.

1.2 High-risk procedures

1.2.1 High risk of bleeding

Table 1 summarizes the estimated risks of bleeding with various endoscopic procedures (1% or more), in settings where the bleeding can be managed endoscopically.

Table 1 The estimated risks of bleeding with various endoscopic procedures

| Procedure | Estimated bleeding risk (%) |

|---|---|

| Colonic polypectomy | 1–2.5 |

| Gastric polypectomy or jumbo/snare biopsy | 4 |

| Endoscopic mucosal resection | ≤22 |

| Ampullectomy | 8 |

| Endoscopic sphincterotomy | 2.5–5 |

| Photodynamic therapy | ≤6 |

| Endoscopic treatment of esophageal or gastric varices | ≤6 |

| Endoscopic hemostasis of vascular lesions | ≤5 |

2 Bleeding associated with antithrombotic therapy

2.1 Antiplatelet drugs

These drugs inhibit platelet function, particularly activation and aggregation.

3 Risks associated with discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy

3.1 Patients receiving oral anticoagulants

3.1.1 Indications associated with acute thromboembolic risk (Table 2)

When taking a patient off warfarin, it is essential to use a specific protocol (Box 2) involving unfractionated heparin. It is also advisable to carefully weigh whether the planned procedure is truly indicated, and if so, undertake procedures associated with a low risk of bleeding (e.g. insertion of a biliary stent without sphincterotomy).

Table 2 Conditions associated with acute thromboembolic risk during interruption of antithrombotic therapy

| Condition | Target INR |

|---|---|

| All prosthetic metal valves in a mitral position | 3–4.5 |

| All first-generation metal aortic valves | 3–4.5 |

| Second-generation aortic valves in patients with an additional embolic risk factor | 3–4.5 |

| Atrial fibrillation associated with other thromboembolic risk factors, particularly mitral valve disease | 2–3 |

Box 2 Patients receiving warfarin

Switching medications in patients with acute thromboembolic risk

3.1.2 Indications associated with low or moderate thromboembolic risk (Box 3)

Box 3 Indications associated with low or moderate thromboembolic risk

Temporary discontinuation of antithrombotic therapy is usually sufficient in these situations.

3.2 Patients receiving antiplatelet drugs

3.2.1 Indications associated with acute thromboembolic risk (Box 4)

Box 4 Patients receiving antiplatelet drugs

Switching medications in patients with acute thromboembolic risk

4 Switching from warfarin or antiplatelet drugs to alternative therapy

No drug has been approved for switching from warfarin or antiplatelet therapy. The discontinuation/switching procedure takes account of the treatment currently being used and the patient’s thromboembolic risk factors (Boxes 2 and 4).

LMWHs are an alternative and are administered using the same protocol as for switching to warfarin.

6 Recommendations

6.2 Setting-specific therapy adjustments

6.2.1 High-risk procedures

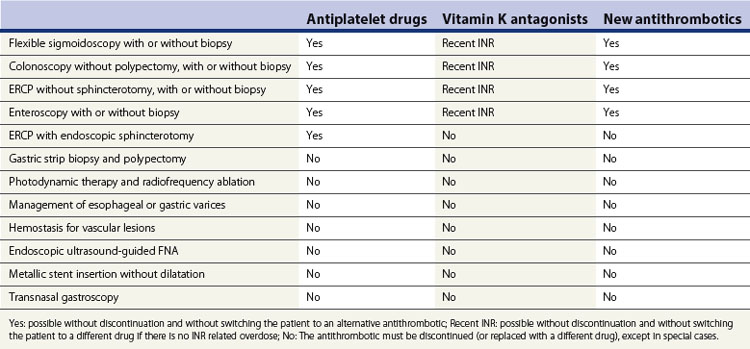

Elevated risk of bleeding (1% or more), if the patient can be treated endoscopically (Table 3):

Low risk of bleeding (<1%) in patients who cannot be monitored endoscopically:

6.3 Treatment discontinuation and resumption

Conclusion

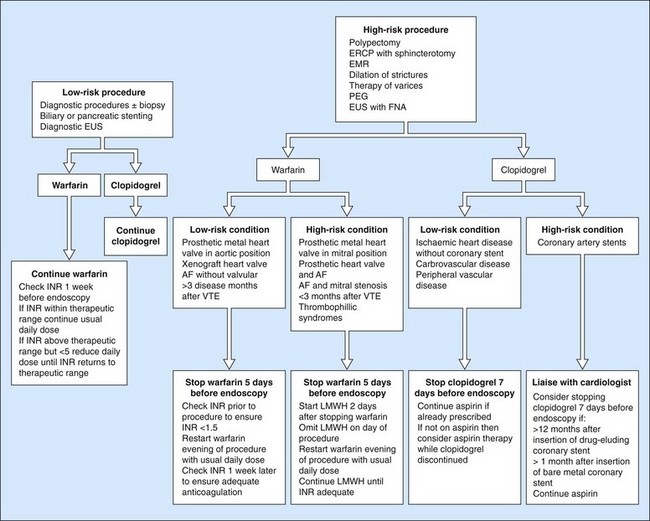

It is difficult to formulate recommendations that will cover all possible clinical scenarios that endoscopists will encounter. The bleeding risk associated with the procedure and the underlying pathology (thromboembolic risk) must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Clear communication between the endoscopist and the prescribing physician is important in deciding the best strategy. The guidance provided in this chapter can potentially serve as a basis for such discussions but it should be borne in mind that this consensus is somewhat arbitrary in places because of lack of an evidence base for recommendations and also because guidelines differ from country to country. The British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines, for example, include a simple, practical flowchart that is a useful starting point for many of the common clinical situations (Fig. 1).

American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060-1070.

Boustière C, Veitch A, Vanbiervliet, et al. Endoscopy and antiplatelet agents. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2011;43(5):445-461.

Hui AJ, Wong RM, Ching JY, et al. Risk of colonoscopy polypectomy bleeding with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents: analysis of 1657 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:44-48.

Patrono C, Coller B, Dalen JE, et al. Platelet-active drugs: the relationships among dose, effectiveness, and optimal therapeutic range. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):39S-63S.

Samama CM, Djoudi R, Lecompte T, et alAFSSAPS Expert Group. Perioperative platelet transfusion: recommendations of the Agence française de sécurité sanitaire des produits de santé (AFSSAPS)] 2003. and the. Can J Anesth. 2005;52:30-37.

Stein PD, Alpert JS, Bussey HI, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with mechanical and biological prosthetic heart valves. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):220S-227S.

Veitch AM, Baglin TP, Gershlick SH, et al. Guidelines for the management of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gut. 2008;57:1322-1329.

Yousfi M, Gostout CJ, Baron TH, et al. Postpolypectomy lower gastrointestinal bleeding: potential role of aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(9):1785-1789.

Zuckerman MJ, Hirota WK, Adler DG, et al. ASGE guideline: the management of low-molecular-weight heparin and nonaspirin antiplatelet agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:189-194.

2.2 Antibiotic prophylaxis

Key Points

Introduction

European and American Society guidelines (Table 1) have recently changed significantly with respect to antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis. Antibiotics are no longer recommended for gastrointestinal procedures in the absence of established infection, but are still recommended for patients with evidence of infection prior to endoscopy and in patients undergoing specific procedures, which are discussed below.

Table 1 Specific society recommendations for prophylaxis of infective endocarditis in high risk patients

| Society | Recommendation | Further Reading |

|---|---|---|

| AHA 2007 | Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis is not recommended for non-dental procedures such as transesophageal echocardiogram, EGD or colonoscopy in the absence of active infection. | Wilson et al 2007; Nishimura et al 2008 |

| NICE 2008 | Antibiotic prophylaxis for gastrointestinal procedures is not recommended. | Richey et al 2008 |

| ESC | Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for gastroscopy, colonoscopy, or transesophageal echocardiography. | Habib et al 2009 |

| BSG | Antibiotics are not indicated as prophylaxis against infective endocarditis. | Allison et al 2009 |

| ASGE | Antibiotic prophylaxis for infectious endocarditis is not recommended. | Banerjee et al 2008 |

AHA, American Heart Association; NICE, National Institute for Heath and Clinical Excellence; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; BSG, British Society of Gastroenterology; ASGE, American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

1 Antibiotics for the prevention of infective endocarditis

European and American societies have recently significantly altered their recommendations for endocarditis prophylaxis in patients undergoing endoscopy (see Further Reading). The rationale for these changes has been summarized by the European Society of Cardiology:

The incidence of transient bacteremia varies greatly in studies. Transient bacteremia occurs frequently in daily routine activities such as brushing teeth, flossing or chewing. It therefore appears that a large proportion of cases of infective endocarditis arise from these daily activities and are not procedure related.

The incidence of transient bacteremia varies greatly in studies. Transient bacteremia occurs frequently in daily routine activities such as brushing teeth, flossing or chewing. It therefore appears that a large proportion of cases of infective endocarditis arise from these daily activities and are not procedure related. The procedure-related risk of a patient developing infective endocarditis ranges from 1 : 14 000 000 for dental procedures in the average population to 1 : 95 000 for patients with previous infectious endocarditis. These estimates demonstrate the huge number of patients that require treatment to prevent a single case of infective endocarditis.

The procedure-related risk of a patient developing infective endocarditis ranges from 1 : 14 000 000 for dental procedures in the average population to 1 : 95 000 for patients with previous infectious endocarditis. These estimates demonstrate the huge number of patients that require treatment to prevent a single case of infective endocarditis. In the majority of patients, no procedure preceded the development of infective endocarditis. Therefore, infective endocarditis prophylaxis may at best protect a small proportion of patients, while the bacteremia that causes infective endocarditis in the majority of patients appears to derive from another source.

In the majority of patients, no procedure preceded the development of infective endocarditis. Therefore, infective endocarditis prophylaxis may at best protect a small proportion of patients, while the bacteremia that causes infective endocarditis in the majority of patients appears to derive from another source.2 Antibiotic prophylaxis in specific groups of patients

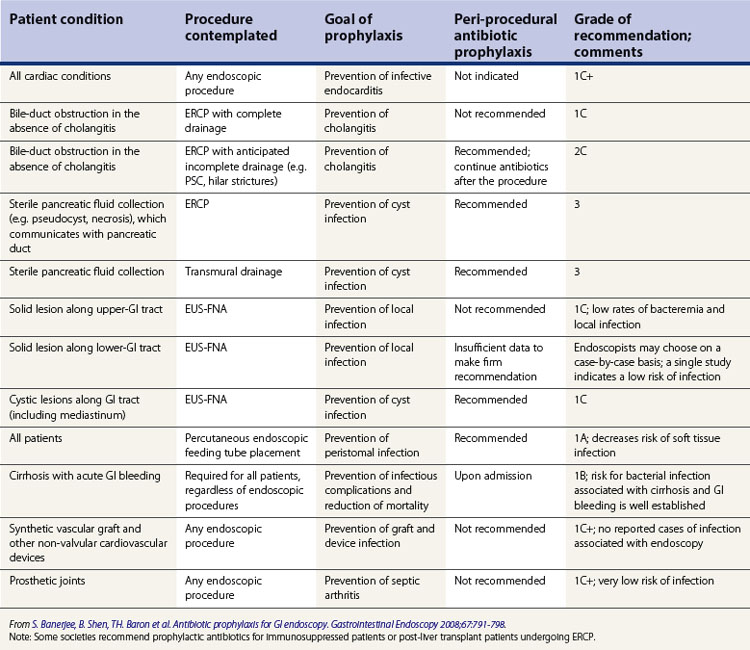

The guidelines of the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy can be found in Table 2.

2.2 Vascular grafts or prostheses

Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for patients with vascular grafts or prostheses.

3 Antibiotic prophylaxis for specific endoscopic procedures

See Table 3 for recommended antibiotics based on the British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines.

| Procedure | Antibiotic coverage |

|---|---|

| ERCP | Ciprofloxacin 750 mg PO 90 min pre-procedure |

| or | |

| Gentamicin 1.5 mg/kg IV | |

| OLT undergoing ERCP | Ciprofloxacin 750 mg 90 min pre-procedure |

| or | |

| Gentamicin 1.5 mg/kg IV | |

| PLUS | |

| Amoxicillin 1 g IV or vancomycin 20 mg/kg IV infused over at least one hour | |

| EUS FNA cystic lesion | Co-amoxiclav 1.2 g IV |

| or | |

| Ciprofloxacin 750 mg PO 90 min pre-procedure | |

| 3–5 day course of antibiotics post-procedure is usually given | |

| Antibiotics should be given prior to performing EUS-FNA | |

| PEG | Co-amoxiclav 1.2 g IV |

| or | |

| Second or third generation cephalosporin (i.e. cefuroxime 750 mg IV) | |

| Teicoplanin 400 mg IV can be used in patients who are penicillin allergic | |

| Antibiotics should be given prior to commencing the procedure | |

| Cirrhosis with upper-GI bleed | Piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g IV three times per day |

| or | |

| Third generation cephalosporin (i.e. cefotaxime 2 g IV three times per day) |

PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram; OLT, orthotopic liver transplant; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; FNA, fine needle aspiration biopsy.

a Based on British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines. Oral antibiotics should be given 60–90 min pre-procedure to allow absorption of the drug.

3.1 ERCP

Recommendations for patients undergoing ERCP:

Allison MC, Sandoe JA, Tighe R, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut. 2009;58:869-880.

(Guidelines of the British Society of Gastroenterology)

Banerjee S, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:791-798.

(Guidelines of the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy)

Danchin N, Duval X, Leport C. Prophylaxis of infective endocarditis: French recommendation v2002. Heart. 2005;91:715-718.

Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, et al. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis. The task force on the prevention, diagnosis, and the treatment of infective endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2369-2413.

Nishimura RA, Carabello BA, Faxon DP, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 Guideline update on valvular heart disease: focused update on infective endocarditis. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2008;118:887-896.

(Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association)

Richey R, Wray D, Stokes T. Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;336:770-771.

Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis. Guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116:1736-1754.

2.3 Sedation

Key Points

Introduction

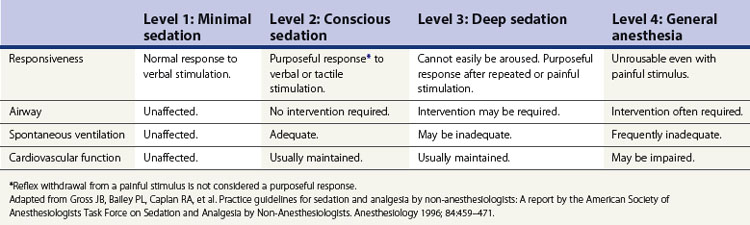

Sedation is defined as a drug-induced depression. There are four levels of sedation, ranging from minimal sedation to general anesthesia (Table 1). The majority of endoscopic procedures are performed under conscious sedation, which is also known as moderate sedation. The aim of sedation is to improve patient comfort. This in turn means that the patient moves less, allowing a better assessment of the endoscopic problem. This is particularly useful where a difficult or prolonged procedure is undertaken.

1 Pre-procedure assessment

1.1 Inpatient versus outpatient sedation

Patients who are suitable for outpatient sedation are as follows:

Patients who do not fulfill these criteria should be admitted overnight.

1.2 Pre-sedation assessment

All patients should be assessed prior to sedation. The aim of this assessment is to identify aspects of the patient’s history and examination that could adversely affect endoscopic sedation. A brief history and examination are required, including airway assessment and determining ASA status (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3 American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) co-morbidity status

| ASA class | Description |

|---|---|

| I | The patient is normal and healthy. |

| II | The patient has mild systemic disease that does not limit their activities (e.g. controlled diabetes or hypertension without systemic sequelae). |

| III | The patient has moderate or severe systemic disease, which does limit their activities (e.g. stable angina or diabetes with systemic sequelae). |

| IV | The patient has a severe systemic disease that is a constant potential threat to life (i.e. decompensated heart failure, end-stage renal failure). |

| V | The patient is morbid and is at substantial risk of death within 24 hour. |

Table 2 History and examination assessment prior to sedation

| History | Physical examination |

|---|---|

a These patients are more likely to have a difficult airway.

b ASA guidelines state that patients should fast a minimum of 2 hour for clear liquids and 6 hour for light meal before sedation.

d The following physical factors can be associated with difficult airway management: obesity, short neck, limited neck extension, hyoid-mental distance <3 cm in adult), neck mass, cervical spine disease or trauma, tracheal deviation, dysmorphic facial features (e.g. Pierre–Robin syndrome), inability to open mouth >3 cm, edentulous, protruding incisors, loose teeth, macroglossia, tonsillar hypertrophy, nonvisible uvula, micrognathia, retrognathia, trismus, significant malocclusion.

1.3 Which patients should be referred for anesthetic input?

Anesthetic input should be considered for the following patients:

1.4 Items which need to be documented during endoscopy and sedation

Box 2 lists the key items which must be documented during the procedure.

Box 2

Key documentation for sedation

2 Monitoring and equipment

Patients undergoing endoscopic procedures should have continuous monitoring (both visual and devices) before, during, and after the procedure. A nurse or assistant should be present throughout the procedure. It is important that they have an understanding of the stages of sedation, monitoring, interpretation of physiologic parameters, and can initiate appropriate intervention in the event of a complication. One member of the team must be able to provide advanced cardiac life support, establish an airway and provide positive pressure ventilation if required. Emergency equipment that should be available at all times in an endoscopy unit is listed in Box 3.

Box 3

Emergency resuscitative equipment

aAll appropriate sizes should be available.

bThe American Society of Anesthesiologists also suggest having nitroglycerin, amiodarone, methylprednisolone, dexamethasone, diazepam or midazolam (American Society of Anesthesiologists 2002).

Modified from Cohen LB, Deluge MH, Isenberg J et al. AGA Institute review of endoscopic sedation. Gastroenterology 2007; 133:675–701.

2.1 Personnel and emergency equipment

A nurse or assistant with appropriate training should be present throughout the procedure. They should have a thorough understanding of the stages of sedation, monitoring, and interpretation of physiologic parameters, as well as the skills to initiate appropriate intervention in the event of a complication. One member of the team must be certified in advanced cardiac life support and be capable of establishing an airway and providing positive pressure ventilation. Emergency equipment (see Box 3) must be available at all times. AGA guidelines suggest that in moderate sedation, the assistant may perform short, interruptible tasks; however, in deep sedation, their only role is observation and monitoring of the patient (Riphaus et al 2009).

2.2 Assessment of level of consciousness

The patient’s level of sedation should be documented prior to commencing sedation, during the procedure and until discharge. There are four different stages of sedation (Table 1) from minimal to general anesthesia. A combination of a benzodiazepine and an opioid is often used to provide conscious sedation, while propofol is used for deep sedation. The level of sedation required for a procedure depends on patient factors such as co-morbidity and anxiety levels, as well as procedural factors such as the complexity of the procedure and discomfort it will generate (i.e. esophageal dilatation). Usually, conscious sedation is sufficient for diagnostic upper endoscopy and colonoscopy, while deeper sedation is required for EUS and ERCP.

3 Drugs

The most commonly used drugs are discussed below, followed by their reversal agent (Note: there is no reversal agent for propofol!). The commonest side-effects have been listed for each drug, while a complete list of side-effects associated with each drug can be found at: www.sedationfacts.org. FDA categories (Table 4) have been given for each drug for use in pregnancy. A detailed discussion of the use of sedation medications in pregnant or lactating women can be found in Guidelines for Endoscopy in Pregnant and Lactating Women, Gastrointest Endosc, 2005.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Adequate, well-controlled studies in pregnant women have not shown an increased risk of fetal abnormalities. |

| B | Animal studies have revealed no evidence of harm to the fetus; however, there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women, or, |

| Animal studies have shown an adverse effect, but adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus. | |

| C | Animal studies have shown an adverse effect and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women, or, |

| No animal studies have been conducted and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. | |

| D | Adequate well-controlled or observational studies in pregnant women have demonstrated a risk to the fetus; however, the benefits of therapy may outweigh the potential risk. |

| X | Adequate well-controlled or observational studies in animals or pregnant women have demonstrated positive evidence of fetal abnormalities; use of the product is contraindicated in women who are or may become pregnant. |

Adapted from Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Adler DG et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. ASGE Guideline: Guidelines for endoscopy in pregnant and lactating women. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61(3):357–362.

3.1 Anesthetic agents

3.1.1 Propofol

A number of short-acting intravenous general anesthetics are used by anesthetists to provide general anesthesia, one of which is propofol. Propofol (Table 5) is an ideal drug for endoscopy with a rapid onset of action, short half-life, and amnesic properties. Recently, the use of propofol within endoscopy has increased, leading to a debate as to whether only an anesthetist is adequately trained to give propofol or whether gastroenterologist-directed propofol (GD-P) is safe and medicolegally reasonable. There is increasing evidence that propofol can safely be administered by non-anesthesiologists. A recent worldwide multicenter review of 521 000 patients given propofol for endoscopy found that between 0.1 and 0.4 per 1000 patients required assisted ventilation. Four patients required endotracheal intubation, one suffered a neurological injury and there were three deaths, which all occurred in patients with significant co-morbidity, underscoring the importance of seeking anesthetic input for any patient with an ASA >3. Currently, the decision to deliver gastroenterologist-directed propofol is often dictated by institutional guidelines or legal restrictions and it is important to check what the local gastroenterology society or legal guidelines are.

| Side-effects | Hypotension |

| Respiratory depression and apnea | |

| Pain at the injection site | |

| Myoclonus | |

| Contraindications | Children under the age of 3 |

| Pregnant women or nursing mothers | |

| Known hypersensitivity to propofol or any component of its formulation | |

| Use with care | Patients with cardiac, respiratory, hepatic or renal impairment |

| Patients with substantial blood loss or hypotension | |

| Use in pregnant women | FDA Category B |

| Interactions | Drugs which will potentiate the effect of propofol |

| Benzodiazepines | |

| Narcotics | |

| Reversal agent | None |

Dose

3.1.2 Benzodiazepines

3.1.2.1 Midazolam

Midazolam (Table 6) has a peak onset of action of 1–2 minutes, with a peak effect within 3–4 minutes. Its onset of action is more rapid if combined with an opioid (1.5 minutes), and sedation deeper. The pharmacokinetic profile is linear, over 0.05–0.4 mg/kg, allowing predictable dosage titration. Its duration of effect is 15–80 minutes. Midazolam is metabolized in the liver and secreted in the urine. Plasma clearance is reduced in the elderly, the obese, and patients with renal or hepatic impairment. The bioavailability of midazolam is increased by 30% in patients using a histamine H2-receptor antagonist.

| Side-effects | Respiratory depression |

| Hypotension (especially when combined with an opioid) | |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias (rare) | |

| Paradoxical restlessness, agitation, disinhibitiona | |

| Contraindications | Narrow angle glaucoma (midazolam lowers intraocular pressure)b |

| Myasthenia gravis | |

| Known hypersensitivity to diazepam or any component of its formulation | |

| Use with care | Elderly |

| Chronic obstructive airway disease (COAD) | |

| Use in pregnant women | FDA Category D |

| Increased risk of congenital malformations suggested in several studies in the 1st trimester | |

| Interactions | Drugs which will potentiate the effect of midazolam: |

| Alcohol, analgesics, anti-epileptics, anxiolytics, depressants, neuroleptics, tranquilizers | |

| Cytochrome P-450 inhibitors – HAARTc, erythromycin, fluconazole, diltiazem | |

| Drugs which will decrease the effect of midazolam: | |

| Cytochrome P-450 inducers – phenytoin, rifampicin, carbamazepine | |

| Reversal agent | Flumazenil |

a Consider this side-effect in patients who become increasingly agitated, despite increasing doses of midazolam.

b May be used in patients with open-angle glaucoma if they are on appropriate therapy.

c HAART, highly active anti-retroviral therapy.

Dose

3.1.2.2 Diazepam

Diazepam (Table 7) has an onset of action of 2–3 minutes with a peak effect after 3–5 minutes, with a duration of 360 minutes. It is metabolized in the liver to active metabolites which undergo renal excretion. This half-life is increased in patients with hepatic or renal impairment.

| Side-effects | Respiratory depression, dyspnea |

| Thrombophlebitis | |

| Contraindications | Acute narrow-angle glaucoma |

| Open angle glaucoma (unless on appropriate therapy) | |

| Myasthenia gravis | |

| Known hypersensitivity to diazepam or any component of its formulation | |

| Use with care | Patients with hepatic, renal or cardiopulmonary impairment |

| Use in pregnant women | FDA Category D |

| Increased risk of congenital malformation in the first trimester suggested in several studies | |

| Interactions | Drugs which will potentiate the effect of diazepam: |

| Antifungal agents (itraconazole, ketoconazole), cimetidine, disulfiram, fluvoxamine, isoniazid, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (i.e. delavirdine, efavirenz), protease inhibitors (i.e. indinavir), macrolide antibiotics (i.e. erythromycin), OCP, omeprazole | |

| Drugs which will decrease the effect of diazepam: | |

| Rifamycin, theophyllines | |

| Drugs which diazepam may increase the effects of: | |

| Digoxin | |

| Reversal agent | Flumazenil |

3.1.2.3 Reversal agent for benzodiazepines: Flumazenil

Flumazenil (Table 8) antagonizes benzodiazepines by competitively inhibiting GABA receptors. It antagonizes the CNS effects of benzodiazepines reversing respiratory depression, over sedation, psychomotor impairment, and memory loss. It has an onset of action of 1–2 minutes, with a peak effect after 3 minutes, and an average duration of 1 hour. It is metabolized in the liver.

| Side-effects | Anxiety, agitation, seizures |

| Contraindications | Patients who have been given a benzodiazepine for potentially life-threatening condition (e.g. control of intracranial pressure or status epilepticus) |

| Patients with signs of serious tricyclic antidepressant overdose | |

| Known hypersensitivity to flumazenil or any component of its formulation | |

| Use with care | Patients on long-term benzodiazepines, chloral hydrate, carbamazepine or high-dose tricyclic antidepressants, as it may precipitate withdrawal symptoms or convulsions |

| Flumazenil is not recommended in epileptic patients taking benzodiazepines as it may cause convulsions | |

| Use in pregnant women | FDA Category C |

| Interactions | Flumazenil will block the effects of non-benzodiazepines acting on the BDZ receptors |

3.2 Opioid analgesics

3.2.1 Fentanyl

Fentanyl (Table 9) is a synthetic opioid. It is highly potent with 100 µg (0.1 mg) equivalent to 10 mg of morphine or 75 mg of pethidine (meperidine). It has a rapid onset of action of 1–2 minutes, with a peak effect within 3–5 minutes and a duration of action of 30–60 minutes. It is metabolized in the liver to active metabolites, which are excreted in the urine.

| Side-effects | Respiratory depression (dose dependent) |

| Hypotension | |

| Bradycardia (responsive to atropine) | |

| Contraindications | Myasthenia gravis (can cause severe muscle rigidity) |

| MAOIs: other narcotic analgesics have been reported to interact with MAOIs (see pethidine). Although this has not been reported for fentanyl, there are insufficient data to establish that this does not occur and fentanyl should therefore not be given to patients taking MAOIs | |

| Known hypersensitivity to fentanyl or any component of its formulation | |

| Use with care | Fentanyl can cause severe bronchospasm and should be used with extreme caution in patients with asthma |

| Patients with respiratory, hepatic or renal impairment | |

| Patients with bradycardia | |

| Use in pregnant women | FDA Category C |

| Interactions | Drugs which will potentiate the effect of fentanyl: |

| CNS depressors (benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, hypnotics) | |

| Reversal agent | Naloxone |

MAOIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

3.2.2 Pethidine (meperidine)

Pethidine (Table 10) is a synthetic opioid with sedative and analgesic properties. It has an onset of action of 3–6 minutes, with a peak effect at 6–7 minutes. Its duration of effect is 60–180 minutes. It is converted into an active metabolite, normeperidine, in the liver and is excreted in the kidneys.

| Side-effects | Respiratory depression |

| Hypotension | |

| Irritability, tremors, agitation and convulsions | |

| Contraindications | Myasthenia gravis |

| MAOIs within the previous 14 days as pethidine may cause sweating, excitation, rigidity, hypertension, hypotension or coma | |

| Known hypersensitivity to pethidine or any component of its formulation | |

| Use with care | Patients with renal impairment and the elderly |

| Use in pregnant women | FDA Category B |

| Does not appear to be teratogenic in two studies and is preferred over morphine or fentanyl which are both Category C | |

| Interactions | Drugs which will potentiate the effect of pethidine: |

| CNS depressors (e.g. benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, hypnotics) | |

| Reversal agent | Naloxone |

MAOIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors. These include dextroamphetamine, Emsam, iproniazid, iproclozide, isocarboxazid, linezolid, moclobemide, nialamide, phenelzine, rasagiline, selegiline, toloxatone, tranylcypromine.

3.2.3 Reversal agent for opioids: naloxone

Naloxone (Table 11) has a similar structure to oxymorphone and antagonizes the CNS effects of opioids including respiratory depression, excess sedation and analgesia. It has an onset of action of 1–2 minutes, a peak effect at 5 minutes and a half-life of 30–45 minutes.

| Side-effects | Pain |

| Hypertension, tachycardia | |

| Pulmonary edema (rare) | |

| Contraindications | Known hypersensitivity to naloxone or any component of its formulation |

| Use in pregnant women | FDA Category B |

| Interactions | No significant interactions |

3.3 Other drugs used for sedation

Several other drugs have been used for sedation including promethazine, dexmedetomidine, droperidol, ketamine, and nitrous oxide. Detailed information about these drugs can be found in Riphaus et al (2009).

4 Management of the complications of sedation

4.2 Respiratory depression/hypoxia

In any patient with hypoxia, the following steps should be taken:

5 Recovery and discharge

5.1 Recovery monitoring

Standardized discharge criteria (Box 5) should be used and followed. All patients who are undergoing outpatient sedation must be driven home and have a friend or relative remain with them overnight. On discharge, patients should receive written instructions and contact numbers in case of emergency. This should include instructions on diet, activity, medication, not to consume alcohol or drive for 24 hour as well as follow-up and a telephone number to be called in case of emergency. It should be stressed to patients that no important decisions should be made during the 24 hour period.

2002 American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by Non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(4):1004-1017.

Cohen LB, Deluge MH, Isenberg J, et al. AGA Institute review of endoscopic sedation. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:675-701.

2003 Guidelines for conscious sedation and monitoring during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:317-322.

2005 Guidelines for endoscopy in pregnant and lactating women. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:357-362.

2002 Guidelines for the use of deep sedation and anesthesia for gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:613-617.

Riphaus T, Wehrmann T, Weber B, et al. S3 Guidelines: sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy 2008. Endoscopy. 2009;41:787-815.

Vargo JJ, Cohen LB, Rex DK, et al. Position statement: nonanesthesiologist administration of propofol for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(6):1053-1059.

2.4 Chromoendoscopy and tattooing

Key Points

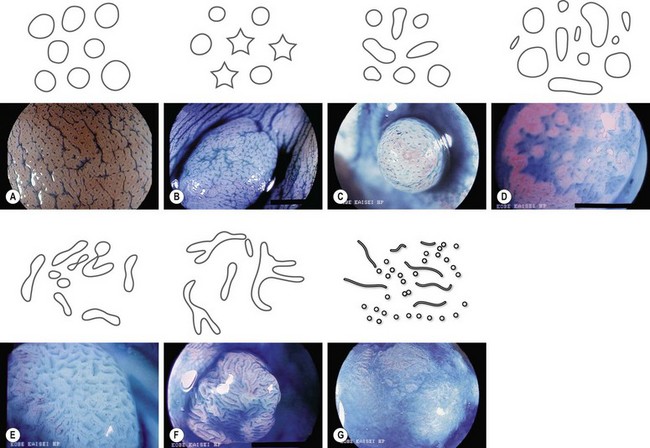

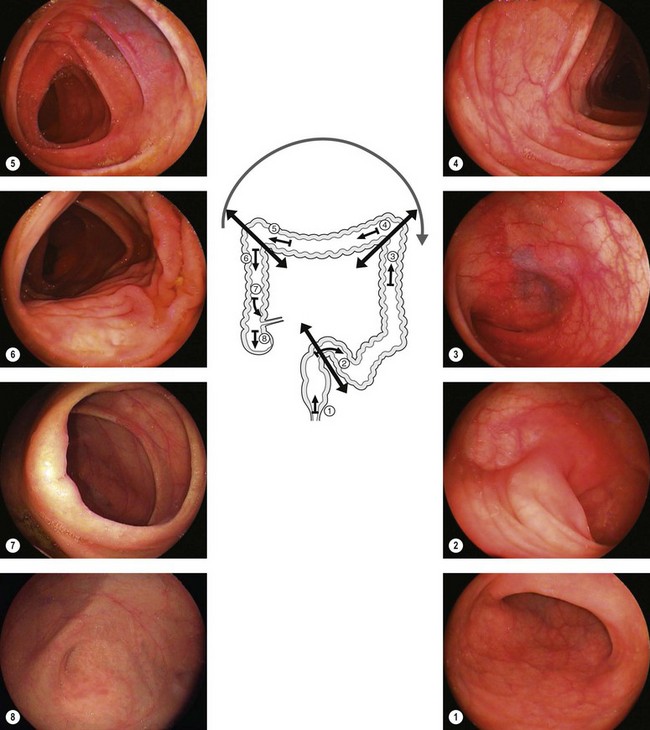

1 Indigo carmine

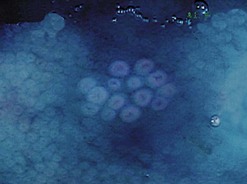

Used in concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 0.4%, indigo carmine is a surface contrast material, i.e. it is not absorbed by the mucosa. This agent brings out relief abnormalities in that it stains the bottom of an ulcer or penetrates fissures, and in so doing delineates a tumor, brings to light polyps that go undetected during standard white light examinations, or shows the central depression on the surface of a polyp that has already undergone malignant transformation (Fig. 1).

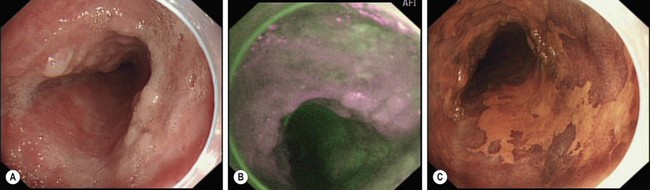

2 Acetic acid

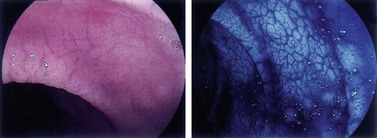

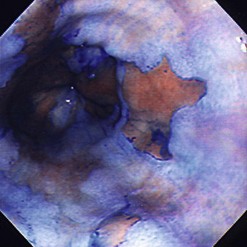

Acetic acid, which has long been used to diagnose cervical cancer at colposcopy, has recently come into use for assessment of Barrett’s esophagus. The chemical whitens inflammatory and dysplastic areas, provoking edema that allows for more precise assessment of the mucosal surface (Fig. 4).

3 Lugol’s iodine

The brownish-black staining obtained with Lugol’s iodine is not homogenous because of the variable concentrations of glycogen in the epithelium. Glycogenic acanthosis accentuates the coloration. Non-stained areas exceeding 5 mm in diameter should be biopsied (Fig. 5).

3.1 Indications

When used solely in the squamous epithelium of the esophagus, Lugol’s iodine allows:

Numerous studies, particularly from Japan, have reported using Lugol’s iodine solution for the detection of early esophageal neoplasia. A study by Dawsey et al (1998) is particularly informative in this regard. In this study, 225 Chinese patients underwent chromoendoscopy using Lugol’s iodine. Prior to staining, all visible lesions were biopsied. After staining, biopsies were taken from areas that exhibited abnormal or no coloration. The sensitivity of endoscopy for the detection of an early malignancy or dysplasia was 62% without staining and 96% with staining, with specificities of 79% and 63%, respectively.

3.3 Staining procedure

4 Methylene blue

Methylene blue, which is absorbed by the mucosa in the colon and small intestine, allows the detection of abnormal intestinal epithelium and for more detailed visualization of the intestinal mucosa (Fig. 6).

4.1 Indications

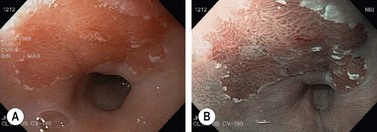

To detect dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus and chronic gastritis. For the stomach, intestinal metaplasia staining displays 96% sensitivity and 95% specificity. For Barrett’s esophagus, Canto et al (2002) demonstrated that specific intestinal metaplasia staining displays 95% sensitivity and 97% specificity. It has also been reported that less intense and somewhat irregular methylene blue impregnation in a stained area suggests the presence of dysplasia (the dysplastic cells do not absorb the contrast material as readily) and can be used to guide biopsies. This latter finding has been contested by other authors.

4.3 Staining procedure

Spray the acetylcysteine solution on the target area (Barrett’s esophagus or gastric atrophy). Wait 1 minute and then spray methylene blue on the area. Wait 2 minutes. Irrigate abundantly using ×3 50 mL syringes while suctioning the fluid regularly to avoid pulmonary aspiration. Biopsy the blue areas, i.e. areas that exhibit irregular coloration (Fig. 7).

6 Crystal violet

Crystal violet is absorbed by intestinal gland orifices (Fig. 8).

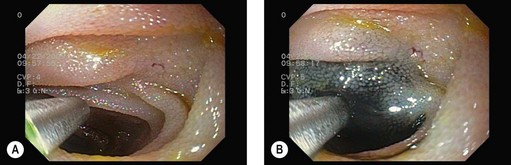

7 Tattooing

Tattooing of the gastrointestinal wall (usually the colon) is useful for marking the location of a lesion or for endoscopic surveillance of an area where, for example, a large or malignant polyp has been removed (Fig. 9). A sterile carbon suspension (e.g. Sterimark; GI Spot), rather than India ink should be used.

ASGE Technology Committee. Technology Status Evaluation Report. Endoscopic tattooing. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:811-814.

Askin MP, Waye JD, Fiedler L, et al. Tattoo of colonic neoplasm in 113 patients with a new sterile carbon compound. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(3):339-342.

Canto MI, Yoshida T, Gossner L, et al. Chromoscopy of intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2002;34:330-336.

Dawsey SM, Fleisher DE, Wang GQ, et al. Mucosal iodine staining improves endoscopic visualization of squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in Linxian, China. Cancer. 1998;83(2):220-231.

Fennerty MB, Sampliner RE, McGee DL, et al. Intestinal metaplasia of the stomach: identification by a selective mucosal staining technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38(6):696-698.

Kiesslich R, Von Bergh M, Hahn M, et al. Chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine improves the detection of adenomatous and nonadenomatous lesions in the colon. Endoscopy. 2001;33(12):1001-1006.

Nakamura A, Honma T, Suzyki Y, et al. The usefulness of crystal violet solution for the magnifying observation of colorectal neoplasm. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(4 Part 2):AB64.

2.5 Pre-endoscopy checklist

Key Points

Introduction

The equipment should be checked to ensure that it is in working order prior to commencing with any procedure. All endoscopes must be disinfected prior to use (see Ch. 1.10 for a detailed description of disinfection guidelines).

1 Examination room and equipment check

1.5 Electrosurgical generator

1.6 Endoscope

2 Equipment that should be present

The following is a list of equipment which should be present in each endoscopy suite.

3 Troubleshooting

3.1 The air is not working

3.2 The suction is not working

3.4 Image is too dark

2.6 Endoscopy reports

Key Points

1 Administrative section

This section should provide the following information:

It is important to indicate the patient’s risk of harboring vCJD, as follows:

2 Clinical section

This section should provide the following information:

3 Endoscopy reports

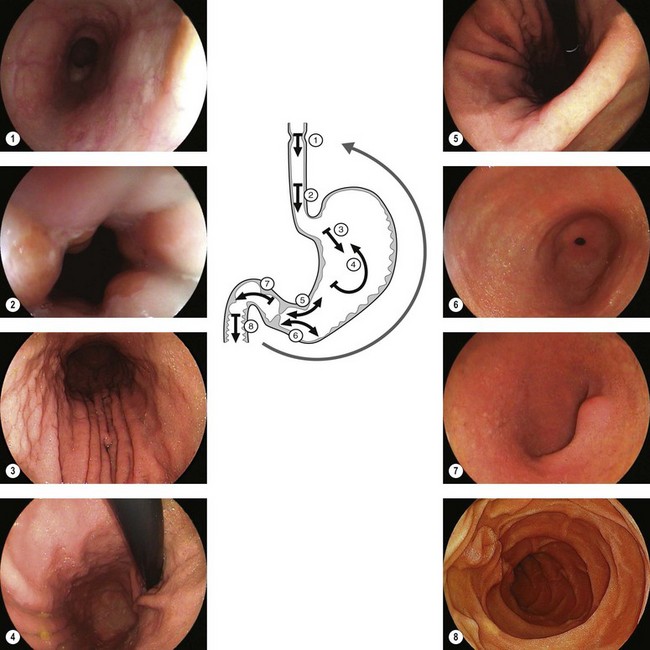

3.1 Upper endoscopy

Figure 1 is an example of the number and quality of images which should be provided.