Chapter 73 Preoperative Pulmonary Evaluation

Postoperative Pulmonary Complications

The frequency of postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) varies with type of surgery, the patient’s health, and the definition of the complication. Pulmonary complications of surgery are at least as common as cardiac complications and may result in prolonged hospital stays, increased morbidity and mortality, and increased costs (Table 73-1).

| Surgery in General | Lung Resection Surgery |

|---|---|

* Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Risk Factors

The many risk factors for PPCs can be classified as patient or surgery related and assigned a simple rating based on the amount and quality of evidence available for support as a risk factor (Table 73-2).

Table 73-2 Selected Risk Factors for Developing Postoperative Pulmonary Complications

| Risk Factor | Level of Prediction |

|---|---|

| Systemic Disease | |

| Asthma (well controlled) | Poor |

| Congestive heart failure | Good |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Good |

| Diabetes mellitus | Fair |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection | I |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Good |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Fair |

| Signs and Symptoms | |

| Abnormal chest auscultation | Good |

| Arrhythmia | I |

| Functionally dependent | Good |

| Impaired mental status | Good |

| Poor exercise capacity | Fair |

| Weight loss | Good |

| Patient Features | |

| Alcohol user | Good |

| Cigarette smoker | Good |

| Corticosteroid use | I |

| Objective Testing | |

| Albumin <35 g/L | Good |

| Blood urea nitrogen >25 mg/dL | Good |

| Chest radiography, abnormal finding | Good |

| Spirometry | I |

| Surgical Site | |

| Aortic aneurysm | Good |

| Abdominal | Good |

| Neurosurgery | Good |

| Vascular | Good |

| Hip | Poor |

| Gynecologic or urologic | Poor |

| Esophageal | I |

| Surgical Factors | |

| Prolonged surgical duration | Good |

| Emergent surgery | Good |

| General anesthesia | Fair |

| Perioperative transfusion | Good |

Good, ACP “A” or “B” rating or other data to support; Fair, ACP “C” rating or other data to support; Poor, ACP “D” rating, or is not a risk factor; I, indeterminate (insufficient data to support a rating.

Data from current American Academy of Chest Physicians (AACP) guidelines; Smetana GW et al: Cleve Clin J Med 73(Suppl 1):36–41, 2006; and other sources (see Suggested Readings).

Patient-Related Factors

A patient’s general health may be assessed by using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification system (Table 73-3). Studies have shown a direct correlation between a higher ASA class and increased pulmonary complications. Patients with an ASA Class III or higher have a twofold to threefold increase in PPCs compared with those with ASA Class II or lower. Difficulty or inability to perform activities of daily living has also been linked to increased complications.

| Class | Patient Status |

|---|---|

| I | Normal healthy patient |

| II | Patient with mild systemic disease (e.g., mild asthma) |

| III | Patient with severe systemic disease, but not incapacitated |

| IV | Patient with life-threatening illness who is incapacitated |

| V | Moribund patient |

| VI | “Brain-dead” patient eligible for organ donation |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Surgery in General

During the history and physical examination, patients should be screened for OSA by asking about snoring, witnessed apneas, and daytime somnolence. Neck circumference and obesity should be noted. Validated questionnaires are available for identifying those at risk for OSA (Box 73-1). Evidence is limited on the usefulness of diagnosing OSA preoperatively with polysomnography, with decisions based on degree of clinical concern and urgency of the surgery.

Box 73-1

Stop-Bang Questionnaire to Screen for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)

1. Snore: can the patient’s snoring be heard through a closed door?

2. Tired: is the patient hypersomnolent during the day?

3. Observed: have there been witnessed apneas?

4. Pressure: does the patient have hypertension?

5. Body mass index: greater than 35?

The patient who answers “yes” to three or more of these eight questions is at high risk for OSA.

Modified from Chung F et al: Anesthesiology 108:812–821, 2008.

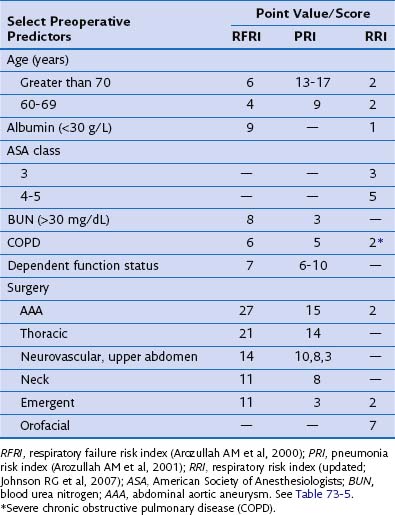

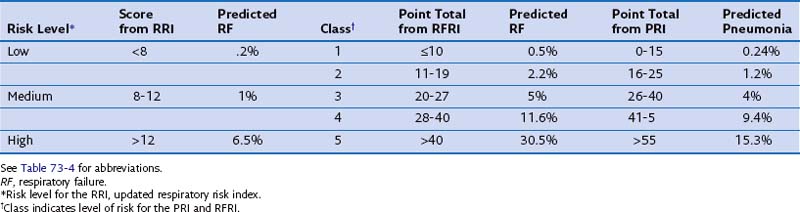

Validated indices are available for predicting postoperative pneumonia and respiratory failure after major noncardiac surgery. The investigators from three select reviews assigned point values to corresponding risk factors, as summarized in Tables 73-4 and 73-5. Clinicians may find these tools helpful in identifying those at risk for postoperative pneumonia and respiratory failure and for selecting perioperative testing and respiratory care for those at high risk.

Lung Resection Surgery

Exercise Testing

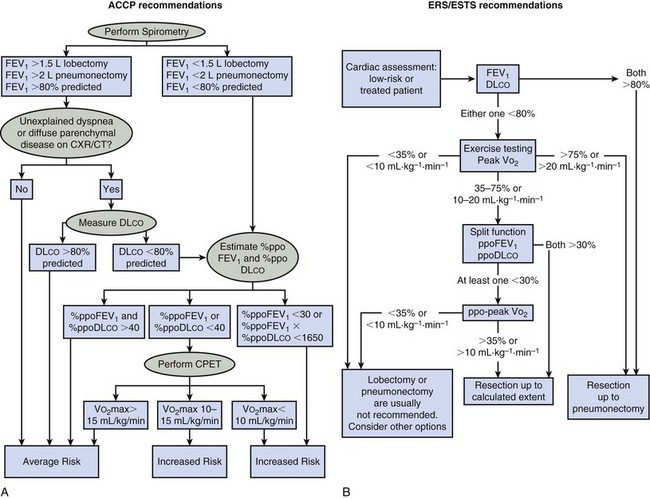

Box 73-2 summarizes the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommendations for the preoperative pulmonary evaluation of the lung resection candidate. Figure 73-1 outlines the ACCP and European Respiratory Society and European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ERS/ESTS) recommended steps to follow when assessing a patient’s pulmonary fitness for lung resection. The differences in these guidelines highlight the lack of consensus in this area and the need to individualize patient decisions.

Box 73-2

Summary of ACCP Guidelines for Lung Cancer Resection

Patients should not be denied lung resection surgery based on age alone.

Patients should not be denied lung resection surgery based on age alone.

All patients should undergo spirometry.

All patients should undergo spirometry.

An FEV1 of 2 L or greater or 80% predicted in a patient without dyspnea or ILD may proceed to pneumonectomy. FEV1 of 1.5 L or greater in a patient without dyspnea or ILD may proceed to lobectomy.

An FEV1 of 2 L or greater or 80% predicted in a patient without dyspnea or ILD may proceed to pneumonectomy. FEV1 of 1.5 L or greater in a patient without dyspnea or ILD may proceed to lobectomy.

If there is undue dyspnea or ILD evident, DLCO is recommended.

If there is undue dyspnea or ILD evident, DLCO is recommended.

If DLCO or FEV1 is less than 80%, ppo lung function should performed.

If DLCO or FEV1 is less than 80%, ppo lung function should performed.

A ppoFEV1 or ppoDLCO less than 40% is consistent with increased PPCs and mortality after resection. Exercise testing is recommended.

A ppoFEV1 or ppoDLCO less than 40% is consistent with increased PPCs and mortality after resection. Exercise testing is recommended.

A postoperative predicted product of less than 1650 or a ppoFEV1 of less than 30% indicates an increased risk for PPCs and death. These patients should be counseled on nonsurgical treatment options.

A postoperative predicted product of less than 1650 or a ppoFEV1 of less than 30% indicates an increased risk for PPCs and death. These patients should be counseled on nonsurgical treatment options.

In patients with a VO2 peak of less than 10 mL/kg/min or a VO2 peak of less than 15, with both ppoFEV1 and ppoDLCO less than 40% predicted, nonsurgical treatment options should be sought.

In patients with a VO2 peak of less than 10 mL/kg/min or a VO2 peak of less than 15, with both ppoFEV1 and ppoDLCO less than 40% predicted, nonsurgical treatment options should be sought.

Patients who walk less than 25 shuttles on two shuttle walks or less than one flight of stairs should be counseled on nonsurgical options.

Patients who walk less than 25 shuttles on two shuttle walks or less than one flight of stairs should be counseled on nonsurgical options.

For those with a PaCO2 greater than 45 mm Hg or SaO2 less than 90%, further testing should be performed prior to surgery.

For those with a PaCO2 greater than 45 mm Hg or SaO2 less than 90%, further testing should be performed prior to surgery.

In lung cancer patients with upper lobe emphysema and FEV1 and DLCO greater than 20%, LVRS combined with resection may be considered.

In lung cancer patients with upper lobe emphysema and FEV1 and DLCO greater than 20%, LVRS combined with resection may be considered.

Modified from American College of Chest Physicians recommendations and Colice GL et al: Chest 132(3 suppl):161–177, 2007.

Arozullah AM, Khuri SF, Henderson WG, Daley J. Participants in the National Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program: development and validation of a multifactorial risk index for predicting postoperative pneumonia after major noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:847–857.

Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812–821.

Colice GL, Shafazand S, Griffin JP, et al. Physiologic evaluation of the patient with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery: American College of Chest Physicians evidenced-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest. 2007;132(3 suppl):161–177.

Johnson RG, Arozullah AM, Neumayer L, et al. Multivariable predictors of postoperative respiratory failure after general and vascular surgery: results from the patient safety in surgery study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1188–1198.

Lim E, Baldwin D, Beckles M, et al. Guidelines on the radical management of patients with lung cancer. British Thoracic Society; Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland. Thorax. 2010;65(suppl 3):1–27.

Mazzone PJ, Arroliga AC. Lung cancer: preoperative pulmonary evaluation of the lung resection candidate. Am J Med. 2005;118:578–583.

Myers K, Hajek P, Hinds C, McRobbie H. Stopping smoking shortly before surgery and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:983–989.

Poonyagariyagorn H, Mazzone PJ. Lung cancer: preoperative pulmonary evaluation of the lung resection candidate. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:271–284.

Smetana GW. Preoperative pulmonary evaluation: identifying and reducing risks for pulmonary complications. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73(suppl 1):36–41.

Smetana GW, Lawrence VA, Cornell JE. Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:581–595.

Sweitzer BJ, Smetana GW. Identification and evaluation of the patient with lung disease. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:1017–1030.