1 Preoperative Preparation

Preoperative Medical Evaluation

Medical History

Medications

Anticoagulation/Antiplatelet Therapy

The clinician needs to find out which medications the patient is taking in order to determine if there will be an increased risk of bleeding in the intraoperative or postoperative period. This includes warfarin, aspirin, NSAIDs, clopidogrel, and low-molecular-weight heparin. For larger surgeries, one might query patients about their use of any vitamin, herbal, or other over-the-counter supplements because some of these can alter the coagulation profile (see Box 1-1).

Box 1-1

Supplements That Alter Coagulation

Source: Adapted from Dinehart SM. Dietary supplements: Altered coagulation and effects on bruising. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:819–826.

Aspirin therapy was not an independent risk factor for bleeding. The researchers concluded that “most postoperative bleeds were inconvenient but not life threatening, unlike the potential risk of thromboembolism after stopping warfarin or aspirin.” They recommended not to discontinue aspirin before skin surgery.1

In a meta-analysis of complications attributed to anticoagulation among patients following cutaneous surgery, a total of six studies representing 1373 patients met criteria for inclusion. Among patients taking aspirin or warfarin, 1.3% and 5.7%, respectively, experienced a severe postoperative complication. Patients taking warfarin were nearly seven times as likely to have a moderate-to-severe complication compared to controls. Patients taking aspirin or NSAIDs were more than twice as likely to have a moderate-to-severe complication compared to controls.2

In 2326 patients operated on by a single surgeon, warfarin was used by 28 patients, 228 took aspirin, and the remainder took neither. There was no difference in the complication rate among the three groups. Researchers concluded that patients taking aspirin or warfarin do not need to discontinue these medications before minor dermatologic procedures.3

In a prospective study of 51 patients undergoing a range of minor cutaneous surgical procedures including excision biopsies, local flaps, and skin grafts, patients continued their normal warfarin regimen. The international normalized ratio (INR) was checked on the day of surgery and it ranged from 1.1 to 4.0. No problems were encountered during surgery, but two patients presented with bleeding postoperatively a few days later. The study concluded that it is not necessary to modify warfarin regimens for minor cutaneous surgery.4

In a prospective controlled observational study, 65 patients on warfarin underwent excision of 70 cutaneous tumors. There was no increase in bleeding tendency during surgery with those on warfarin when compared with controls. Five patients on warfarin (8%) reported moderate or severe postoperative bleeding. All patients on warfarin with bleeding complications had an INR of <2.6 at the time of surgery.5 Bleeding risk could not be correlated with INR. The researchers suggested that it is crucial to observe meticulous hemostasis in all patients on warfarin regardless of INR.5

Warfarin and medically necessary aspirin should be continued as well as clopidogrel and low-molecular-weight heparin.6 Exceptional care must be taken to prevent bleeding by using electrosurgery, tying off vessels, and applying handheld pressure for hemostasis. Pressure dressings can also help minimize the risk of hematoma. Lastly, patients should be made aware of the small but increased risk of postoperative bleeding and given verbal and written postoperative instructions.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Preoperative antibiotics such as oral cephalexin, dicloxacillin, or clindamycin may be recommended for use with patients who have a higher risk of infection.7 These situations might include a patient who has a contaminated or infected lesion; a lesion in an area of increased bacteria, such as the axilla, ear, or mouth; a lesion on a hand or foot, especially in patients with peripheral vascular disease; a situation in which the operation might take more than 1 hour or if the wound was open for more than 1 hour; a patient for whom complete sterile technique was not optimal; or any situation in which an infection would have serious consequences, such as in a patient with diabetes or neutropenia. See Table 1-1 for classification of wound infection risk and the need for antibiotic prophylaxis. The 2008 Advisory Statement from the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) on antibiotic prophylaxis in dermatologic surgery stated that antibiotics may be indicated for the prevention of surgical-site infections for:

|

Class |

Antibiotic Prophylaxis Needed? |

|---|---|

| Clean: noncontaminated skin, sterile technique = 5% infection | No |

| Clean contaminated: wounds in oral cavity, respiratory tract, axilla/perineum; breaks in aseptic technique = 10% infection rate | Consider |

| Contaminated: trauma, acute nonpurulent inflammation, major breaks in aseptic technique (intact, inflamed cysts; tumors with clinical inflammation) = 20% to 30% infection rate | Yes |

| Infected: gross contamination with foreign bodies, devitalized tissue (ruptured cysts; tumors with purulent, necrotic material) = 30% to 40% infection rate | Yes |

Source: From Haas AF, Grekin RC. Antibiotic prophylaxis in dermatologic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:155–176.

Table 1-2 provides recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis in patients at increased risk of surgical-site infection.

TABLE 1-2 Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Patients at Increased Risk of Surgical-Site Infection

|

Surgical Site |

Medication |

Dose* |

|---|---|---|

| Wedge on lip or ear, flap on nose, all grafts | Cephalexin or dicloxacillin | 2 g |

| Groin or lower extremity | Cephalexin or | 2 g |

| TMP-SMX-DS or | 1 tablet | |

| Levofloxacin | 500 mg | |

| Allergic to PCN | ||

| Lip, ear, flap on nose, all grafts | Clindamycin, or | 600 mg |

| Groin or lower extremity | Azithromycin, clarithromycin or | 500 mg |

| TMP-SMX-DS or | 1 tablet | |

| Levofloxacin | 500 mg | |

| Unable to Take Oral Medication | ||

| Lip, ear, flap on nose, all grafts | Cefazolin, ceftriaxone | 1 g IM/IV |

| Groin or lower extremity | Ceftriaxone | 1–2 g IV |

| Unable to Take Oral Medication and Allergic to PCN | ||

| Lip, ear, flap on nose, all grafts | Clindamycin | 600 mg IM/IV |

| Groin or lower extremity | Clindamycin + gentamicin | 600 mg, 2 mg/kg IV |

IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; PCN, penicillin; TMP-SMX-DS, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength.

* Give one hour before surgery.

Source: Adapted from Wright TI, Baddour LM, Berbari EF, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in dermatologic surgery: advisory statement 2008. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:464–473.

In a 5-year prospective observational study, infection incidence was significantly higher in patients with diabetes (4.2%, 23/551) than in those without (2.0%, 135/6673) (p < .001).8 Noninfective complications were similar. Although this study demonstrates the increased risk, it does not prove that antibiotic prophylaxis will decrease this risk. However, the choice to use antibiotic prophylaxis is a complicated decision that should be made based on all available data and known patient risks.

Endocarditis Prophylaxis

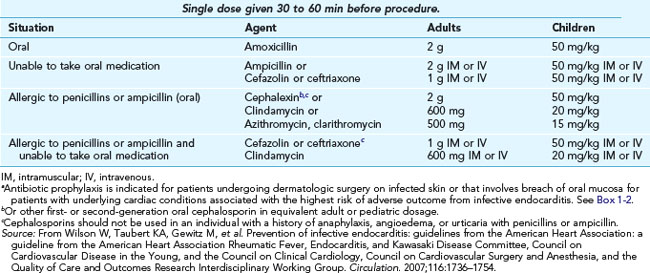

The recommendations of the American Heart Association (AHA) for the prevention of bacterial endocarditis were last published in 2007.9 Endocarditis prophylaxis is not needed for incision or biopsy of noninfected surgically scrubbed skin no matter what endocarditis risk factors are present. The 2007 guidelines state that antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated for patients undergoing dermatologic surgery on infected skin or surgery that involves breach of oral mucosa for patients with underlying cardiac conditions associated with the highest risk of an adverse outcome from infective endocarditis.

For individuals at highest risk for endocarditis who undergo a surgical procedure that involves infected skin or skin structures, it is reasonable for the therapeutic regimen administered for treatment of the infection to contain an agent active against staphylococci and beta-hemolytic streptococci, such as an antistaphylococcal penicillin or a cephalosporin (SOR C).9 Vancomycin or clindamycin may be administered to patients unable to tolerate a beta-lactam antibiotic or who are known or suspected to have an infection caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.9 Suggested antibiotic prophylaxis regimens for dermatologic surgical procedures that breach the oral mucosa or involve infected skin in patients at high risk for infective endocarditis or hematogenous total joint infection are recommended in Table 1-3.7

Box 1-2 High-Risk Cardiac Conditions for Which Antibiotic Prophylaxis Is Indicated with Infected Skin or Breach of Oral Mucosa

One published mnemonic to help remember when and how to use prophylactic antibiotics in skin surgery is I PREVENT. This represents Immunosuppressed patients; patients with a Prosthetic valve; some patients with a joint Replacement; a history of infective Endocarditis; a Valvulopathy in cardiac transplant recipients; Endocrine disorders such as uncontrolled diabetes mellitus; Neonatal disorders including unrepaired cyanotic heart disorders (CHDs), repaired CHD with prosthetic material, or repaired CHD with residual defects; and the Tetrad of antibiotics: amoxicillin, cephalexin, clindamycin, and ciprofloxacin.10

Preoperative Patient Preparation

Preparation of the Skin

The most important part of the preoperative preparation of the skin is the mechanical rubbing of the antiseptic onto the skin with the gauze. Although the gauze may not need to be sterile for the first prep, it might help to use sterile gauze in the last prep. It is actually impossible to sterilize the skin because bacteria can extend into hair follicles. The goal of the preoperative preparation of the skin is to reduce the bacteria on the skin surface by scrubbing the skin with a good antiseptic such as povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine. Povidone-iodine must be allowed to dry on the skin for its effect to be optimal. Chlorhexidine has the advantage of not staining the skin and being easy to wash off. Povidone-iodine has the advantage of being easy to see where it was applied but should be avoided in persons with iodine allergies. However, Darouiche et al. found a greater than 40% reduction in total surgical-site infections among patients undergoing clean-contaminated surgery who had received a single chlorhexidine-alcohol scrub as compared with a povidone-iodine scrub.11

Preparation of Hair

The best method of hair removal over a surgical site is to use scissors to cut the hair. Using scissors to clip hair is now the preferred method for preoperative hair removal because a close shave with a razor causes minute abrasions of the skin that can increase the chance of infection.12 A depilatory cream may also be used but this is messy and more time consuming. A chemical depilatory could be used by the patient the day before surgery if desired. The scalp is the area of the body in which the hairs can most interfere with surgery. Plastering down the hair with petrolatum or other ointment can decrease the number of hairs that interfere with surgery without causing a noticeable loss of hair during the postoperative period. Hair ties and bobby pins are invaluable items to have in the office (Figure 1-2).

Drapes

The use of sterile fenestrated aperture drapes (drapes with a hole) is recommended when suturing is performed so that the sutures do not drag over nonsterile skin (Figure 1-3). Sterile drapes are not necessary for small procedures, such as a shave biopsy, where suturing is not performed. Disposable or linen-quality sterile drapes are adequate for the procedures described in this book. You can create your own aperture drapes by cutting a hole in a sterile disposable drape. This allows you to customize the size of the hole you need. This should be done with sterile suture scissors and not tissue scissors to avoid dulling your more expensive instruments. You can also use the paper that is used to wrap surgical trays before sterilization for this purpose to save money. Drapes can be cut in a variety of sizes with a variety of holes and then sterilized alone or as part of a packet. Some prepackaged disposable sterile drapes come with adhesive around the aperture to stabilize the drape and isolate the field.

1. Dixon AJ, Dixon MP, Dixon JB. Bleeding complications in skin cancer surgery are associated with warfarin but not aspirin therapy. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1356-1360.

2. Lewis KG, Dufresne RGJr. A meta-analysis of complications attributed to anticoagulation among patients following cutaneous surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:160-164.

3. Shalom A, Klein D, Friedman T, Westreich M. Lack of complications in minor skin lesion excisions in patients taking aspirin or warfarin products. Am Surg. 2008;74:354-357.

4. Sugden P, Siddiqui H. Continuing warfarin during cutaneous surgery. Surgeon. 2008;6:148-150.

5. Blasdale C, Lawrence CM. Perioperative international normalized ratio level is a poor predictor of postoperative bleeding complications in dermatological surgery patients taking warfarin. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:522-526.

6. Hurst EA, Yu SS, Grekin RC, Neuhaus IM. Bleeding complications in dermatologic surgery. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:189-195.

7. Wright TI, Baddour LM, Berbari EF, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in dermatologic surgery: advisory statement 2008. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:464-473.

8. Dixon AJ, Dixon MP, Dixon JB. Prospective study of skin surgery in patients with and without known diabetes. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1035-1040.

9. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116:1736-1754.

10. Moorhead C, Torres A. I PREVENT bacterial resistance. An update on the use of antibiotics in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1532-1538.

11. Darouiche RO, Wall MJJr, Itani KMF, et al. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:18-26.

12. Tanner J, Woodings D, Moncaster K. Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD004122.