4 Preoperative Evaluation, Premedication, and Induction of Anesthesia

Preparation of Children for Anesthesia

Fasting

Infants and children are fasted before sedation and anesthesia to minimize the risk of pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents. In a fasted child, only the basal secretions of gastric juice should be present in the stomach. In 1948, Digby Leigh recommended a 1-hour preoperative fast after clear fluids. Subsequently, Mendelson reported a number of maternal deaths that were attributed to aspiration at induction of anesthesia.1 During the intervening 20 years, the fasting interval before elective surgery increased to 8 hours after all solids and fluids. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, an evidence-based approach to the effects of fasting intervals on gastric fluid pH and volume concluded that fasting more than 2 hours after clear fluids neither increased nor decreased the risk of pneumonitis should aspiration occur.2–10 In the past, the risk for pneumonitis was reported to be based on two parameters: gastric fluid volume greater than 0.4 mL/kg and pH less than 2.5; however, these data were never published in a peer-reviewed journal.1,11 In a monkey, 0.4 mL/kg of acid instilled endobronchially, equivalent to 0.8 mL/kg aspirated tracheally, resulted in pneumonitis.12 Using these corrected criteria for acute pneumonitis (gastric residual fluid volume greater than 0.8 mL/kg and pH less than 2.5), studies in children demonstrated no additional risk for pneumonitis when children were fasted for only 2 hours after clear fluids.2–9

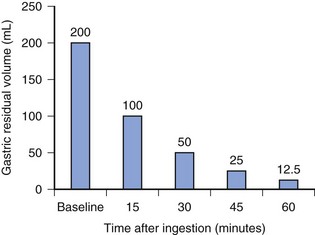

The incidence of pulmonary aspiration in modern routine elective pediatric or adult cases without known risk factors is small.13–16 This small risk is the result of a number of factors including the preoperative fasting schedule. The half-life to empty clear fluids from the stomach is approximately 15 minutes (Fig. 4-1); as a result, 98% of clear fluids exit the stomach in children by 1 hour. Clear liquids include water, fruit juices without pulp, carbonated beverages, clear tea, and black coffee. Although fasting for 2 hours after clear fluids ensures nearly complete emptying of the residual volume, extending the fasting interval to 3 hours introduces flexibility in the operative schedule. The potential benefits of a 2-hour fasting interval after clear fluids include a reduced risk of hypoglycemia, which is a real possibility in children who are debilitated, have chronic disease, are poorly nourished, have metabolic dysfunction, or are preterm or formerly preterm infants.17–20 Additional benefits include decreased thirst, decreased hunger (and thus reduced temptation that the fasting child will “steal” another child’s food), decreased risk for hypotension during induction, and improved child cooperation.2,11,21

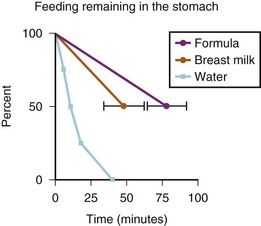

Breast milk, which can cause significant pulmonary injury if aspirated,22 has a very high and variable fat content (determined by maternal diet), which will delay gastric emptying.21 Breast milk should not be considered a clear liquid.23 Two studies estimated the gastric emptying times after clear fluids, breast milk, or formula in full-term and preterm neonates.24,25 The emptying times for breast milk in both age groups were substantively greater than for clear fluids, and the gastric emptying times for formula were even greater than those for breast milk. With half-life emptying times for breast milk of 50 minutes and for formula of 75 minutes, fasting intervals of at least 3.3 hours for breast milk and 5 hours for formula are required. More importantly, perhaps, was the large (15%) variability in gastric emptying times for breast milk and formula in full-term infants (E-Fig. 4-1). Based in part on these data, the Task Force on Fasting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) issued the following guidelines: for breast milk, 4 hours; and for formula, 6 hours (Table 4-1).10

TABLE 4-1 Preoperative Fasting Recommendations in Infants and Children

| Clear liquids* | 2 hours |

| Breast milk | 4 hours |

| Infant formula | 6 hours† |

| Solids (fatty or fried foods) | 8 hours |

*Include only fluids without pulp, clear tea, or coffee without milk products.

†Some centers allow plain toast (no dairy products) up to 6 hours prior to induction.

From Warner MA, Caplan RA, Epstein B. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting. Anesthesiology 1999;90:896-905.

Children who have been chewing gum must dispose of the gum by expectorating it, not swallowing it. Chewing gum increases both gastric fluid volume and gastric pH in children, leaving no clear evidence that it affects the risk of pneumonitis should aspiration occur.26 Consequently, we recommend that if the gum is discarded, then elective anesthesia can proceed without additional delay. If, however, the child swallows the gum, then surgery should be cancelled, because aspirated gum at body temperature may be very difficult to extract from a bronchus or trachea.

When the anesthesiologist suspects that the child has a full stomach, induction of anesthesia should be adjusted appropriately. The incidence of pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents during elective surgery in children ranges from 1 : 1163 to 1 : 10,000, depending on the study.13–1527 In contrast, the frequency of pulmonary aspiration in children undergoing emergency procedures is several times greater, 1 : 373 to 1 : 4544.27 Risk factors for perianesthetic aspiration included neurologic or esophagogastric abnormality, emergency surgery (especially at night), ASA physical status 3 to 5, intestinal obstruction, increased intracranial pressure, increased abdominal pressure, obesity, and the skill and experience of the anesthesiologist.14

The majority of aspirations in children occur during induction of anesthesia, with only 13% occurring during emergence and extubation. In contrast, 30% of the aspirations in adults occur during emergence. Bowel obstruction or ileus was present in the majority of infants and children who aspirated during the perioperative period in one study, with the risk increasing in children younger than 3 years of age.27 A combination of factors predispose the infant and young child to regurgitation and aspiration, including decreased competence of the lower esophageal sphincter, excessive air swallowing while crying during the preinduction period, strenuous diaphragmatic breathing, and a shorter esophagus. In one study, almost all cases of pulmonary aspiration occurred either when the child gagged or coughed during airway manipulation or during induction of anesthesia when neuromuscular blocking drugs were not provided or before the child was completely paralyzed.27

When children do aspirate, the morbidity and mortality are exceedingly small for elective surgical procedures and generally reflect their ASA physical status. In general, most ASA 1 or 2 patients who aspirate clear gastric contents have minimal to no sequelae.13,27 If clinical signs of sequelae from an aspiration in a child are going to occur, they will be apparent within 2 hours after the regurgitation.27 The mortality rate from aspiration in children is exceedingly low, between zero and 1 : 50,000.13,14,27

Piercings

Body piercing is common practice in adolescents and young adults. Single or multiple piercings may appear anywhere on the body. To minimize the liability and risk of complications from metal piercings, they must be removed before surgery. Complications that may occur if they are left in situ during anesthesia are listed in E-Table 4-1.28–30

E-TABLE 4-1 Complications from Metal Piercings

Modified from Rosenberg AD, Young M, Bernstein RL, Albert DB. Tongue rings: just say no. Anesthesiology 1998;89:1279-80; Wise H. Hypoxia caused by body piercing. Anaesthesia 1999;54:1129.

Primary and Secondary Smoking

Primary Smoking

Unfortunately, cigarette smoking is not only limited to adults. Each day, about 6000 American adolescents smoke their first cigarette. Of these, 50% will become regular smokers. Even though two thirds of these adolescents will regret taking up the habit and will want to quit, three quarters of them will not succeed because they are addicted to the nicotine. Sadly, about one third of those who cannot quit will die prematurely due to smoking.31 Even though the rate of new smokers in North America has waned in the past 2 decades, this has been offset by the increasing rate of new smokers in other continents. Media, peer influence, and secondhand smoke exposure play a significant role in influencing initiation of smokers in this age group.32

Smoking is known to increase blood carboxyhemoglobin concentrations, decrease ciliary function, decrease functional vital capacity (FVC) and the forced expiratory flow in midphase (FEF25%-75%), and increase sputum production. There is extensive evidence that smokers undergoing surgery are more likely to develop wound infections and postoperative respiratory complications.33 Although stopping smoking for 2 days decreases carboxyhemoglobin levels and shifts the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve to the right, stopping for at least 6 to 8 weeks is necessary to reduce the rate of postoperative pulmonary complications.34,35

We seldom interview our patients 8 weeks before surgery, but because the perioperative period is the ideal time to abandon the smoking habit permanently, anesthesiologists can perhaps play a more active role in facilitating this process. Physician communication with adolescents regarding smoking cessation has been shown to positively impact their attitudes, knowledge, intentions to smoke, and quitting behaviors.36 In summary, during the preoperative visit with adolescents, anesthesiologists should inquire about cigarette smoking and emphasize the need to stop the habit by offering measures to ameliorate the withdrawal (e.g., nictoine patch).

Secondary Smoking

The World Health Organization has estimated that approximately 700 million children, or almost half of the children in the world, are exposed to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS).37 Children exposed to ETS are more likely to have asthma, otitis media,38 atopic eczema, hay fever,39 and dental caries.40 There is also an increased rate of lower respiratory tract illness in infants with ETS exposure.41,42

Several authors have demonstrated that ETS results in increased perioperative airway complications in children. In one study43 of children receiving general anesthesia, urinary cotinine, the major metabolite of nicotine, was used as a surrogate of ETS. A strong association was found between passive inhalation of tobacco smoke and airway complications on induction and emergence from anesthesia. Other investigators confirmed that ETS exposure was associated with an increased frequency of respiratory complications during emergence and recovery from anesthesia.44

Psychological Preparation of Children for Surgery

Although the preoperative evaluation and preparation of children are similar to those of adults from a physiologic standpoint, the psychological preparation of infants and children is very different (see also Chapter 3). Many hospitals have an open house or a brochure to describe the preoperative programs available to parents before the day of admission.45 However, printed material should not replace verbal communication with nursing and medical staff.46 Anesthesiologists are encouraged to participate in the design of these programs so that they accurately reflect the anesthetic practice of the institution. The preoperative anesthetic experience begins at the time parents are first informed that the child is to have surgery or a procedure that requires general anesthesia. Parental satisfaction correlates with the comfort of the environment and the trust established between the anesthesiologist, the child, and the parents.47 If parental presence during induction is deemed to be in the child’s best interest, a parental educational program that describes what the parent can expect to happen if he or she accompanies the child to the operating room can significantly decrease parents’ anxiety and increase their satisfaction.48 The greater the understanding and amount of information the parents have, the less anxious they will be, and this attitude, in turn, will be reflected in the child.49,50

It has been shown that parents desire comprehensive perioperative information, and that discussion of highly detailed anesthetic risk information does not increase parent’s anxiety level.51 Inadequate preparation of children and their families may lead to a traumatic anesthetic induction and difficulty for both the child and the anesthesiologist, with the possibility of postoperative psychological disturbances.52 Numerous preoperative educational programs for children and adults have evolved to alleviate some of these fears and anxiety. They include preoperative tours of the operating rooms, educational videos, play therapy, magical distractions, puppet shows, anesthesia consultations, and child life preparation.53 The timing of the preoperative preparation has been found to be an important determinant of whether the intervention will be effective. For example, children older than 6 years of age who participated in a preparation program more than 5 to 7 days before surgery were least anxious during separation from their parents, those who participated in no preoperative preparation were moderately anxious, and those who received the information 1 day before surgery were the most anxious. The predictors of anxiety correlated also with the child’s baseline temperament and history of previous hospitalizations.54 Children of different ages vary in their response to the anesthetic experience (see also Chapter 3).55 Even more important may be the child’s trait anxiety when confronted with a stressful medical procedure.56

Child Development and Behavior

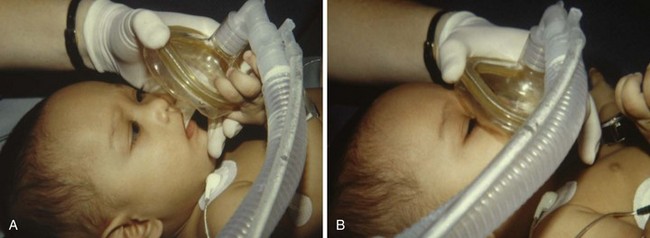

Understanding age-appropriate behavior in response to external situations is essential (E-Table 4-2). Infants younger than 10 months of age tolerate short periods of separation from their parents. Many do not object to an inhalation induction and frequently respond to the smell of the inhalation agents by sucking or licking the mask. These infants usually do not need a sedative premedication.

| Age | Specific Type of Perioperative Anxiety |

|---|---|

| 0-6 months |

Modified with permission from Cruickshank BM, Cooper LJ. Common behavioral problems. In: Greydanus DE, Wolraich ML, editors: Behavioral pediatrics. New York: Springer; 1992.

Children between 11 months and 6 years of age frequently cling to their parents. In an unfamiliar environment such as a hospital, preschool children tend to become very anxious, especially if the situation appears threatening. Their anxiety may be exacerbated if they sense that their parents are anxious. Efforts to educate the parents to allay their anxiety can also reduce the child’s anxiety.45,57,58 A heightened anxiety response may lead to immediate postoperative maladaptive behavior, such as nightmares, eating disturbances, and new-onset enuresis. Compared with other patients, children 2 to 6 years of age are more likely to exhibit problematic behavior when separated from their parents (see also Chapter 3).55 Children who display one or more of the predictive risk factors would probably benefit from a sedative premedication.59–62 They are generally more content if their parents accompany them during induction or if they are sedated in the presence of their parents in a nonthreatening environment before entering the operating room (see later discussion).

Children ages 4 to 10 years may exhibit psychological factors that are predictive of postoperative behavior (e.g., abnormal sleep patterns, parental anxiety, aggressive behavior).63,64 In addition, children who have pain on the day of the operation have behavioral problems that continue well after the pain has been relieved.65 Therefore, preventing postoperative pain decreases and limits the duration of postoperative behavioral problems.

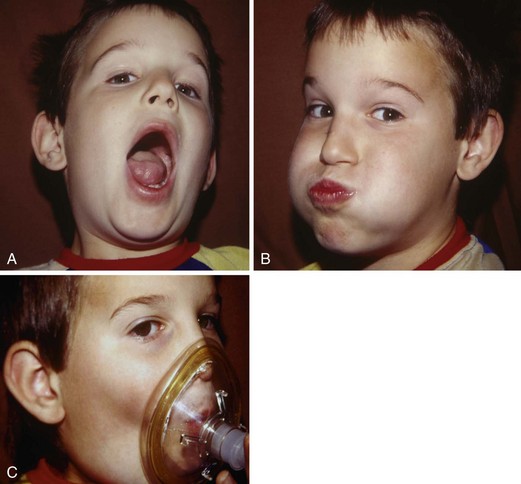

The importance of proper psychological preparation for surgery should not be underestimated. Often, little has been explained to both patient and parents before the day of surgery. Anesthesiologists have a key role in defusing fear of the unknown if they understand a child’s age-related perception of anesthesia and surgery (see Chapter 3). They can convey their understanding by presenting a calm and friendly face (smiling, looking at the child and making eye contact), offering a warm introduction, touching the patient in a reassuring manner (holding a child’s or parent’s hand), and being completely honest. Children respond positively to an honest description of exactly what they can anticipate. This includes informing them of the slight discomfort of starting an intravenous line or giving an intramuscular premedication, the possible bitter taste of an oral premedication, or breathing our magic laughing gas through the flavored mask.

The postoperative process, from the operating room to the recovery room, and the onset of postoperative pain should be described. Encourage the child and family to ask questions. Strategies to maintain analgesia should be discussed, including the use of long-acting local anesthetics; nerve blocks; neuraxial blocks; patient-controlled, nurse-controlled, or parent-controlled analgesia or epidural analgesia; or intermittent opioids (see also Chapters 41, 42, and 43).

It is important to observe the family dynamics to better understand the child and determine who is in control, the parent or the child. Families many times are in a state of stress, particularly if the child has a chronic illness; these parents are often angry, guilt ridden, or simply exhausted. Ultimately, the manner in which a family copes with an illness largely determines how the child will cope.66 The well-organized, open, and communicative family tends to be supportive and resourceful, whereas the disorganized, noncommunicative, and dysfunctional family tends to be angry and frustrated. Dealing with a family and child from the latter category can be challenging. There is the occasional parent who is overbearing and demands total control of the situation. It is important to be empathetic and understanding but to set limits and clearly define the parent’s role. He or she must be told that the anesthesiologist determines when the parent must leave the operating room; this is particularly true if an unexpected development occurs during the induction.

Parental Presence during Induction

One controversial area in pediatric anesthesia is parental presence during induction. Some anesthesiologists encourage parents to be present at induction, whereas others are uncomfortable with the process and do not allow parents to be present. Inviting a parent to accompany the child to the operating room has been interpreted by some courts as an implicit contract on the part of the caregiver who invited the parent to participate in the child’s care; in one case, the institution was found to have assumed responsibility for a mother who suffered an injury when she fainted.67 Each child and family must be evaluated individually; what is good for one child and family may not be good for the next.68–71 (See Chapter 3 for a full discussion of this and other anxiolytic strategies in children.)

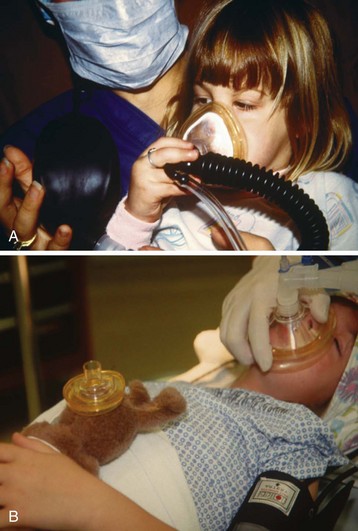

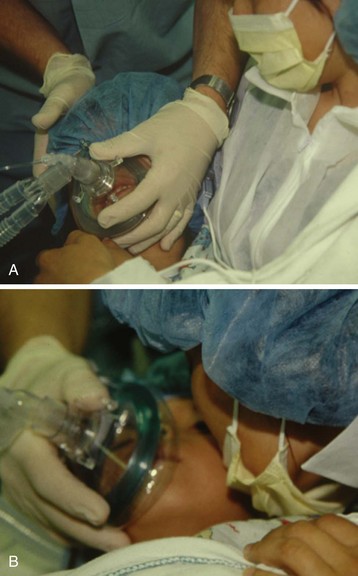

Parents must be informed about what to anticipate in terms of the operating room itself (e.g., equipment, surgical devices), in terms of what they may observe during induction (e.g., eyes rolling back, laryngeal noises, anesthetic monitor alarms, excitation), and when they will be asked to leave. They must also be instructed regarding their ability to assist during the induction process, such as by comforting the child, encouraging the child to trust the anesthesiologist, distracting the child, and consoling the child (Video 4-1)![]() . Personnel should be immediately available to escort parents back to the waiting area at the appropriate time. Someone should also be available to care for a parent who wishes to leave the induction area or who becomes lightheaded or faints. An anesthesiologist’s anxiety about parents’ presence during induction decreases significantly with experience.72

. Personnel should be immediately available to escort parents back to the waiting area at the appropriate time. Someone should also be available to care for a parent who wishes to leave the induction area or who becomes lightheaded or faints. An anesthesiologist’s anxiety about parents’ presence during induction decreases significantly with experience.72

Explaining what parents might see or hear is essential. We generally tell parents the following:

History of Present Illness

A review of all organ systems (Table 4-2) with special emphasis on the organ system involved in the surgery

A review of all organ systems (Table 4-2) with special emphasis on the organ system involved in the surgery

Medications (over-the-counter and prescribed) related to and taken before the present illness, including herbals and vitamins, and when the last dose was taken

Medications (over-the-counter and prescribed) related to and taken before the present illness, including herbals and vitamins, and when the last dose was taken

Medication allergies with specific details of the nature of the allergy and whether immunologic testing was performed

Medication allergies with specific details of the nature of the allergy and whether immunologic testing was performed

Previous surgical and hospital experiences, including those related to the current problem

Previous surgical and hospital experiences, including those related to the current problem

Timing of the last oral intake, last urination (wet diaper), and vomiting and diarrhea. It is essential to recognize that decreased gastrointestinal motility often occurs with an illness or injury.

Timing of the last oral intake, last urination (wet diaper), and vomiting and diarrhea. It is essential to recognize that decreased gastrointestinal motility often occurs with an illness or injury.

| System | Factors to Assess | Possible Anesthetic Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory |

In the case of a neonate, problems that may have been present during gestation and birth may still be relevant in the neonatal period and beyond (E-Table 4-3). The maternal medical and pharmacologic history (both therapeutic and drug abuse) may also provide valuable information for the management of a neonate requiring surgery.

E-TABLE 4-3 Maternal History with Commonly Associated Neonatal Problems

| Maternal History | Commonly Expected Problems with Neonate |

|---|---|

| Rh-ABO incompatibility | |

| Toxemia |

• SGA and its associated problems,* muscle relaxant interaction with magnesium therapy |

| Hypertension | |

| Drug addiction | |

| Infection | |

| Hemorrhage | |

| Diabetes | |

| Polyhydramnios | |

| Oligohydramnios | |

| Cephalopelvic disproportion | |

| Alcoholism |

SGA, Small for gestational age; LGA, large for gestational age.

Past/Other Medical History

Herbal Remedies

Increasing numbers of children are ingesting herbal medicine products. During the preoperative interview, anesthesiologists should include specific inquiries regarding the use of these medications because of their potential adverse effects and drug interactions. Hospital surveys suggest that the use of herbal remedies ranges from 17% to 32%73–75 of presurgical patients, and 70% of these patients do not inform their anesthesiologist of such use.

In Hong Kong, 80% of patients undergoing major elective surgery use prepacked over-the-counter traditional Chinese herbal medicines, and 8% use medicines prescribed by traditional Chinese medicine practitioners.76 The prescription users of traditional Chinese medicines experienced a greater incidence of adverse perioperative events. In particular, this group was twice as likely to have hypokalemia or impaired hemostasis (i.e., prolonged international normalized prothrombin ratio [INR] and activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT]) than nonusers, although there was no significant difference in the incidence of perioperative events between self-prescribed users and nonusers. To further complicate this subject, there is an important difference between Chinese and Western herbs. Traditional Chinese herbal medicines consist of multiple herbs that are combined for their effects, whereas Western herbs are usually ingested as a single substance.77

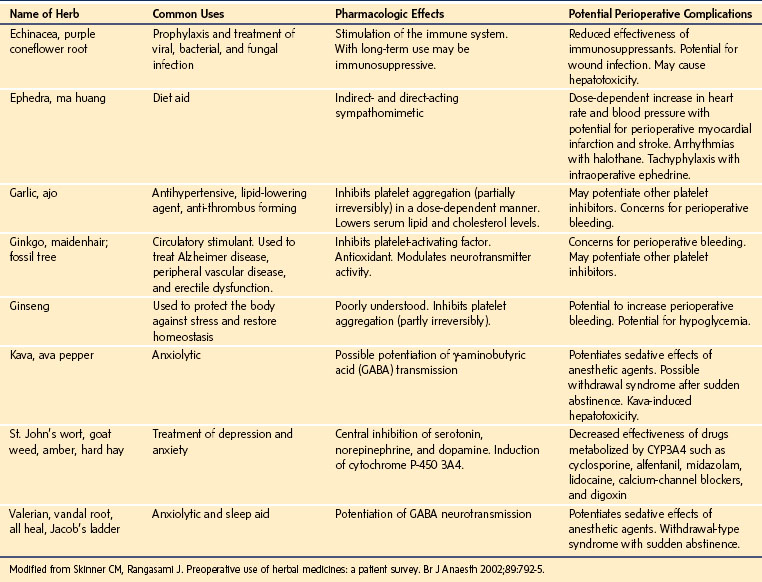

Herbal medicines are associated with cardiovascular instability, coagulation disturbances, prolongation of anesthesia, and immunosuppression.78 The most commonly used herbal medications reported are garlic, ginseng, Ginkgo biloba, St. John’s wort, and echinacea.79 The three “g” herbals, together with feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium), potentially increase the risk of bleeding during surgery. The amount of active ingredient in each preparation may vary, the dose taken by a child may also vary, and detection of a change in platelet function and other subtle coagulation disturbances may be difficult. St. John’s wort is the herb that most commonly interacts with anesthetics and other medications, usually via a change in drug metabolism, because it is a potent induction of the cytochrome P-450 enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4) and P-glycoprotein. A potentially fatal interaction between cyclosporine and St. John’s wort has been well documented.80–83 Heart, kidney, or liver transplant recipients who were stabilized on a dose of cyclosporine experienced decreased plasma concentrations of cyclosporine and, in some cases, acute rejection episodes after taking St. John’s wort. A summary of the most commonly used herbal remedies and their potential perioperative complications is shown in E-Table 4-4.

E-TABLE 4-4 Pharmacologic Effects and Potential Perioperative Complications of Eight Commonly Used Herbal Remedies

To avoid potential perioperative complications, the ASA has encouraged the discontinuation of all herbal medicines 2 weeks before surgery,84 although this recommendation is not evidence based. Indeed, some herbs such as valerian, a treatment for insomnia (Valeriana officinalis), should not be discontinued abruptly but tapered; otherwise, abrupt discontinuation may result in a paradoxical and severe reaction.85 Each herb should be carefully evaluated using standard resource texts, and a decision should be made regarding the timing of or need for discontinuation as determined on a case-by-case basis.86

Anesthesia and Vaccination

What do anesthesiologists think about anesthesia and vaccination? An international survey87 revealed that only one third of responding anesthesiologists had the benefit of a hospital policy, ranging from a formal decision to delay surgery to an independent choice by the anesthesiologist. Sixty percent of respondents would anesthetize a child for elective surgery within 1 week of receiving a live attenuated vaccine (such as oral polio vaccine or measles, mumps, and rubella [MMR] vaccine), whereas 40% would not. The survey also revealed that 28% of anesthesiologists would delay immunization for 2 to 30 days after surgery.

Is there a consensus statement on anesthesia and vaccination? A scientific review of the literature associating anesthesia and vaccination in children resulted in recommendations for the care of children under these circumstances.88 The review demonstrated a brief and reversible influence of vaccination on lymphoproliferative responses that generally returned to preoperative values within 2 days. Vaccine-driven adverse events (e.g., fever, pain, irritability) might occur but should not be confused with perioperative complications. Adverse events to inactivated vaccines such as diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DPT) become apparent from 2 days and to live attenuated vaccines such as MMR from 7 to 21 days after immunization.88 Therefore, appropriate delays between immunization and anesthesia are recommended by type of vaccine to avoid misinterpretation of vaccine-associated adverse events as perioperative complications. Because children remain at risk of contracting vaccine-preventable diseases, the minimum delay seems prudent, especially in the first year of life. Likewise, it seems reasonable to delay vaccination after surgery until the child is fully recovered. Other immunocompromised patients, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive children, cancer patients, and transplant recipients, have distinct underlying immune impairments, and the influence of anesthesia on vaccine responses has not been comprehensively investigated.

Allergies to Medications and Latex

Most cases of reported penicillin allergy consist of a maculopapular rash after oral penicillin. This occurs in 1% to 4% of children receiving penicillin or in 3% to 7% of those taking ampicillin, usually during treatment.89 Rarely are signs or symptoms that suggest an acute (immunoglobulin E–mediated) allergic reaction present (i.e., angioedema), and even less frequently is skin testing conducted to establish penicillin allergy. Given the frequency of penicillin allergy, most of these unverified allergies in fact are not allergies to penicillin but rather minor allergies to the dye in the liquid vehicle or a consequence of the (viral) infection. If the child has not received penicillin for at least 5 years since the initial exposure and has not been diagnosed with a penicillin allergy by an immunologist or allergist, then a reexposure is warranted. If the child has been tested immunologically for penicillin allergy, then it is best to avoid this class of antibiotics. Although there is a 5% to 10% cross-reactivity between first-generation cephalosporins and penicillin, there is no similar cross-reactivity with second- and third-generation cephalosporins. To date, there have been no fatal anaphylactic reactions in penicillin allergic children from a cephalosporin.89

Latex allergy is an acquired immunologic sensitivity resulting from repeated exposure to latex, usually on mucous membranes (e.g., children with spina bifida or congenital urologic abnormalities who have undergone repeated bladder catheterizations with latex catheters, those with more than four surgeries, those requiring home ventilation). It occurs more frequently in atopic individuals and in those with certain fruit and vegetable allergies (e.g., banana, chestnut, avocado, kiwi, pineapple).90–96 For a diagnosis of latex anaphylaxis, the child should have personally experienced an anaphylactic reaction to latex, skin-tested positive for anaphylaxis to latex, or experienced swelling of the lips after touching a toy balloon to the lips or a swollen tongue after a dentist inserted a rubber dam into the mouth.96 The avoidance of latex within the hospital will prevent acute anaphylactic reactions to latex in children who are at risk.97 Latex gloves and other latex-containing products should be removed from the immediate vicinity of the child. Prophylactic therapy with histamine H1 and H2 antagonists and steroids do not prevent latex anaphylaxis.90,98 Latex anaphylaxis should be treated by removal of the source of latex, administration of 100% oxygen, acute volume loading with balanced salt solution (10 to 20 mL/kg repeated until the systolic blood pressure stabilizes), and administration of intravenous epinephrine (1 to 10 µg/kg according to the severity of the anaphylaxis). In some severe reactions, a continuous infusion of epinephrine alone (0.01 to 0.2 µg/kg/min) or combined with other vasoactive medications may be required for several hours.

Laboratory Data

The laboratory data obtained preoperatively should be appropriate to the history, illness, and surgical procedure. Routine hemoglobin testing or urinalysis is not indicated for most elective procedures; the value of these tests is questionable when the surgical procedure will not involve clinically significant blood loss.99 There are insufficient data in the literature to make strict hemoglobin testing recommendations in healthy children. A preoperative hemoglobin value is usually determined only for those who will undergo procedures with the potential for blood loss, those with specific risk factors for a hemoglobinopathy, formerly preterm infants, and those younger than 6 months of age. Coagulation studies (platelet count, INR, and PTT) may be indicated if major reconstructive surgery is contemplated, especially if warranted by the medical history, and in some centers before tonsillectomy. In addition, collection of a preoperative type-and-screen or type-and-crossmatch sample is indicated in preparation for potential blood transfusions depending on the nature of the planned surgery and the anticipated blood loss.

In general, routine chest radiography is not necessary; studies have confirmed that routine chest radiographs are not cost-effective in children.100,101 The oxygen saturation of children who are breathing room air is very helpful. Baseline saturations of 95% or less suggest clinically important pulmonary or cardiac compromise and warrant further investigation.

Pregnancy Testing

Although pregnancy rates among teenagers in the United States are declining,102 a small percentage of young women may still present for elective surgery with an unsuspected pregnancy. In 2003, the birth rate in girls aged 15 to 19 years was 41.6 births per 1000, and for girls aged 10 to 14 years it was 0.6 per 1000. However, routine preoperative pregnancy testing in adolescent girls may present ethical and legal dilemmas, including social and confidentiality concerns. This places the anesthesiologist in a predicament when faced with a question of whether to perform routine preoperative pregnancy screening.102 Each hospital should adopt a policy regarding pregnancy testing to provide a consistent and comprehensive policy for all females who have reached menarche.

A survey of members of the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia practicing in North America revealed that pregnancy testing was routinely required by approximately 45% of the respondents regardless of the practice setting (teaching versus nonteaching facilities).99 A retrospective review of a 2-year study of mandatory pregnancy testing in 412 adolescent surgical patients103 revealed that the overall incidence of positive tests was 1.2%. Five of 207 patients aged 15 years and older tested positive, for an incidence of 2.4% in that group. None of the 205 patients younger than the age of 15 years had a positive pregnancy test.

The most recent ASA Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation104 recognized that a history and physical examination may not adequately identify early pregnancy and issued the following statement: “The literature is insufficient to inform patients or physicians on whether anesthesia causes harmful effects on early pregnancy. Pregnancy testing may be offered to female patients of childbearing age and for whom the result would alter the patient’s management.”105 Because of the risk of exposing the fetus to potential teratogens and radiation from anesthesia and surgery, the risk of spontaneous abortion, and the risk of apoptosis reported in the rapidly developing fetal animal brain, elective surgery with general anesthesia is not advised during early pregnancy. Therefore, if the situation is unclear, and when indicated by medical history, it is best to perform a preoperative pregnancy test. If the surgery is required in a patient who might be pregnant, then using an opioid-based anesthetic such as remifentanil and the lowest concentration of inhalational agent or propofol that provides adequate anesthesia is preferred.

Premedication and Induction Principles

General Principles

The major objectives of preanesthetic medication are to (1) allay anxiety, (2) block autonomic (vagal) reflexes, (3) reduce airway secretions, (4) produce amnesia, (5) provide prophylaxis against pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents, (6) facilitate the induction of anesthesia, and (7) if necessary, provide analgesia. Premedication may also decrease the stress response to anesthesia and prevent cardiac arrhythmias.106 The goal of premedication for each child must be individualized. Light sedation, even though it may not eliminate anxiety, may adequately calm a child so that the induction of anesthesia will be smooth and a pleasant experience. In contrast, heavy sedation may be needed for the very anxious child who is unwilling to separate from his or her parents.

The route of administration of premedicant drugs is very important. Premedications have been administered by many routes including the oral, nasal, rectal, buccal, intravenous, and intramuscular routes. Although a drug may be more effective and have a more reliable onset when given intranasally or intramuscularly, most pediatric anesthesiologists refrain from administering parenteral medication to children without intravenous access. Many children who are able to verbalize report that receiving a needle puncture was their worst experience in the hospital.107,108 In most cases, medication administered without a needle will be more pleasant for children, their parents, and the medical staff. Oral premedications do not increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia unless large volumes of fluids are ingested.109 In general, the route of delivery of the premedication should depend on the drug, the desired drug effect, and the psychological impact of the route of administration. For example, a small dose of oral medication may be sufficient for a relatively calm child, whereas an intramuscular injection (e.g., ketamine) may be best for an uncooperative, combative, extremely anxious child. Intramuscular administration may be less traumatic for this type of child than forcing him or her to swallow a drug, giving a drug rectally, or forcefully holding an anesthesia mask on the face.110

Since Water’s classic work in 1938 on premedication of children, numerous reports have addressed this subject.111 Despite the wealth of studies, no single drug or combination of drugs has been found to be ideal for all children. Many drugs used for premedication have similar effects, and a specific drug may have various effects in different children or in the same child under different conditions.

Medications

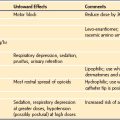

Several categories of drugs are available for premedicating children before anesthesia (Table 4-3). Selection of drugs for premedication depends on the goal desired. Drug effects should be weighed against potential side effects, and drug interactions should be considered. Premedicant drugs include tranquilizers, sedatives, hypnotics, opioids, antihistamines, anticholinergics, H2-receptor antagonists, antacids, and drugs that increase gastric motility.

TABLE 4-3 Doses of Drugs Commonly Administered for Premedication

| Drug | Route | Dose (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Barbiturates | ||

| Methohexital | Rectal | (10% solution) 20-40 |

| Intramuscular | (5% solution) 10 | |

| Thiopental | Rectal | (10% solution) 20-40 |

| Benzodiazepines | ||

| Diazepam Midazolam |

Oral | 0.1-0.5 |

| Rectal | 1 mg/kg | |

| Oral | 0.25-0.75 | |

| Nasal | 0.2 | |

| Rectal | 0.5-1 | |

| Intramuscular | 0.1-0.15 | |

| Lorazepam | Oral | 0.025-0.05 |

| Phencyclidine | ||

| Ketamine* | Oral | 3-6 |

| Nasal | 3 | |

| Rectal | 6-10 | |

| Intramuscular | 2-10 | |

| α2-Adrenergic Agonist | ||

| Clonidine | Oral | 0.004 |

| Opioids | ||

| Morphine Meperidine† Fentanyl Sufentanil |

Intramuscular | 0.1-0.2 |

| Intramuscular | 1-2 | |

| Oral | 0.010-0.015 (10-15 µg/kg) | |

| Nasal | 0.001-0.002 (1-2 µg/kg) | |

| Nasal | 0.001-0.003 (1-3 µg/kg) | |

†Only a single dose is recommended due to metabolites that may cause seizures.

Tranquilizers

Benzodiazepines

Midazolam, a short-acting, water-soluble benzodiazepine with an elimination half-life of approximately 2 hours, is the most widely used premedication for children.112,113 The major advantage of midazolam over other drugs in its class is its rapid uptake and elimination.114 It can be administered intravenously, intramuscularly, nasally, orally, and rectally with minimal irritation, although it leaves a bitter taste in the mouth or nasopharynx after oral or nasal administration, respectively.115–121 Peak plasma concentrations occur approximately 10 minutes after intranasal midazolam administration, 16 minutes after rectal administration, and 53 minutes after oral administration.114,121,122 The relative bioavailability of midazolam is approximately 90% after intramuscular injection, 60% after intranasal administration, 40% to 50% after rectal administration, and 30% after oral administration, compared with intravenous administration (see Chapter 6).122,123 After oral or rectal administration, there is incomplete absorption and extensive hepatic extraction of the drug during the first pass through the liver—hence, the need for large doses through these routes. Most children are adequately sedated after receiving a midazolam dose of 0.025 to 0.1 mg/kg intravenously, 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg intramuscularly, 0.25 to 0.75 mg/kg orally, 0.2 mg/kg nasally, or 1 mg/kg rectally.

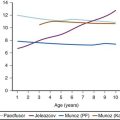

Orally administered midazolam is effective in calming most children and does not increase gastric pH or residual volume.124,125 The current formulation of oral midazolam (2 mg/mL) is a commercially prepared, strawberry-flavored liquid. Two multicenter studies yielded slightly different responses to this preparation of oral midazolam in children.126,127 In one study, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/kg all produced satisfactory sedation and anxiolysis within 10 to 20 minutes,127 whereas in the other study, 1.0 mg/kg provided greater anxiolysis and sedation than 0.25 mg/kg.126 These differing results may be attributed to the older ages of children in the former study.126

Recent evidence suggests that the required dose of midazolam increases as age decreases in children, similar to that for inhaled agents and intravenous agents.128 An increased clearance in younger children contributes to their increased dose requirement.129 Thus, greater doses may be required in younger children to achieve a similar degree of sedation and anxiolysis. However, the formulation of the oral solution may also attenuate its effectiveness.130,131 A number of medications that affect the cytochrome oxidase system, significantly affect the first-pass metabolism of midazolam, including grapefruit juice, erythromycin, protease inhibitors, and calcium-channel blockers that decrease CYP3A4 activity, which in turn increases the blood concentration of midazolam and prolongs sedation.132–138 Conversely, anticonvulsants (phenytoin and carbamazepine), rifampin, St. John’s wort, glucocorticoids, and barbiturates induce the CYP3A4 isoenzyme, thereby reducing the blood concentration of midazolam and its duration of action.* The dose of oral midazolam should be adjusted in children who are taking these medications.

Concerns have been raised about possible delayed discharge after premedication with oral midazolam. Oral midazolam, 0.5 mg/kg, administered to children 1 to 10 years of age did not affect awakening times, time to extubation, postanesthesia care unit, or hospital discharge times, after sevoflurane anesthesia.139 Similar results have been reported in children and adolescents after 20 mg of oral midazolam, however, detectable preoperative sedation in this group of children was predictive of delayed emergence.140 In children aged 1 to 3 years undergoing adenoidectomy as outpatients, premedication with oral midazolam, 0.5 mg/kg, slightly delayed spontaneous eye opening by 4 minutes and discharge by 10 minutes compared with placebo; children who had been premedicated, however, exhibited a more peaceful sleep at home on the night after surgery.141

Likely the greatest effect of oral midazolam on recovery occurs with its use in children undergoing myringotomy and tube insertion, a procedure that normally takes 5 to 7 minutes. In this surgery, the use of this premedication must be carefully considered. Oral midazolam decreased the infusion requirements of propofol by 33% during a propofol-based anesthesia, although the time to discharge readiness was delayed.142 After oral midazolam premedication (0.5 mg/kg), induction of anesthesia with propofol, and maintenance with sevoflurane, emergence and early recovery were delayed by 6 and 14 minutes, respectively, in children 1 to 3 years of age compared with unpremedicated children, although discharge times did not differ.143 Increased postoperative sedation may be attributed to synergism between propofol and midazolam on γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors.144

One notable benefit of midazolam is anterograde amnesia; children who were amnestic about their initial dental extractions tolerated further dental treatments better than those who were not amnestic.145 It appears that memory becomes impaired within 10 minutes and anxiolytic effects are apparent as early as 15 minutes after oral midazolam.146

Although anxiolysis and a mild degree of sedation occur in most children after midazolam, a few develop undesirable adverse effects. Some children become agitated after oral midazolam.147 If this occurs after intravenous midazolam (0.1 mg/kg), intravenous ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) may reverse the agitation.148 Adverse behavioral changes have been reported in the postoperative period after midazolam premedication. One study found that oral midazolam suppresses crying during induction of anesthesia but may cause adverse behavioral changes (nightmares, night terrors, food rejection, anxiety, and negativism) for up to 4 weeks postoperatively compared with placebo149; this finding has not been substantiated.59 One undesirable effect associated with midazolam, independent of the mode of administration (rectal, nasal, or oral), is hiccups (approximately 1%); the etiology is unknown.

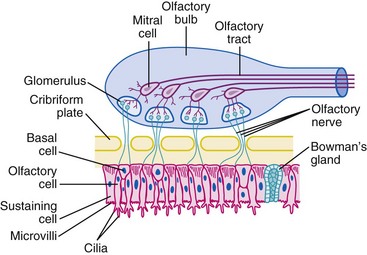

Anxiolysis and sedation usually occur within 10 minutes after intranasal midazolam,150 although it may be less effective in children with an upper respiratory tract infection (URI) and excessive nasal discharge.121 Intranasal midazolam does not affect the time to recovery or discharge after surgical procedures at least 10 minutes in duration.151,152 Although midazolam reduces negative behavior in children during parental separation, nasal administration is not well accepted because it produces irritation, discomfort, and a burning aftertaste that may overshadow its positive sedative effects.153–155 Another theoretical concern for the nasal route of administration of midazolam is its potential to cause neurotoxicity via the cribriform plate.121 There are direct connections between the nasal mucosa and the central nervous system (CNS) (E-Fig. 4-2). Medications administered nasally reach high concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid very quickly.156–158 To date, no such sequelae have been reported. Because midazolam with preservative has been shown to cause neurotoxicity in animals, we recommend only preservative-free midazolam for nasal administration.159,160

Sublingual midazolam (0.2 mg/kg) has been reported to be as effective as, and better accepted than, intranasal midazolam.161 Oral transmucosal midazolam given in three to five small allotments (0.2 mg/kg total dose) placed on a child’s tongue (8 months to 6 years of age) was found to provide satisfactory acceptance and separation from parents in 95% of children.162

There is another pharmacodynamic difference among benzodiazepines that is important to consider when these drugs are administered intravenously. Entry into the CNS is directly related to fat solubility.163,164 The greater the fat solubility, the more rapid the transit into the CNS. The time to peak CNS electroencephalographic effect in adults is 4.8 minutes for midazolam but only 1.6 minutes for diazepam (see Fig. 47-7). Therefore, when administering intravenous midazolam, one must wait an adequate interval between doses to avoid excessive medication and oversedation.

Diazepam is only used for premedication of older children. In infants and especially preterm neonates, the elimination half-life of diazepam is markedly prolonged because of immature hepatic function (see Chapter 6). In addition, the active metabolite (desmethyldiazepam) has pharmacologic activity equal to that of the parent compound and a half-life of up to 9 days in adults.165 The most effective route of administration of diazepam is intravenous, followed by oral and rectal. The intramuscular route is not recommended because it is painful and absorption is erratic.166–170 The combination of oral midazolam 0.25 mg/kg and diazepam 0.25 mg/kg has been shown to provide better sedation at induction of anesthesia and less agitation during emergence than oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy.171 The average oral dose for premedicating healthy children with diazepam ranges from 0.1 to 0.3 mg/kg; however, doses as large as 0.5 mg/kg have been used.172 A rectal solution of diazepam is more effective and reliable than rectally administered tablets or suppositories.170,173 The recommended dose of rectal diazepam is 1 mg/kg, and the peak serum concentration is reached after approximately at 20 minutes.173 When compared with rectal midazolam, rectal diazepam is less effective.174

Lorazepam (0.05 mg/kg) is reserved primarily for older children. Lorazepam causes less tissue irritation and more reliable amnesia than diazepam. It can be administered orally, intravenously, or intramuscularly and is metabolized in the liver to inactive metabolites. Compared with diazepam, the onset of action of lorazepam is slower and its duration of action is prolonged. Whereas these characteristics make it a suitable premedication for inpatients, there are disadvantages for outpatients. When given the night before surgery to children undergoing reconstructive burn surgery, oral lorazepam, 0.025 mg/kg, significantly decreased preoperative anxiety.175 The intravenous formulation of lorazepam is avoided in neonates because it may be neurotoxic.176,177

Barbiturates

The relatively short-acting barbiturates thiopental and methohexital may be given rectally to premedicate young children who refuse other modes of sedation. These drugs are usually administered in the presence of the parents who may hold the toddler until he or she is sedated.178 The usual dose of rectal thiopental is 30 mg/kg. This dose produces sleep in about two thirds of the children within 15 minutes.179,180 The elimination half-life of intravenous thiopental (9 ± 1.6 hours) is almost threefold greater than that of methohexital (3.9 ± 2.1 hours) owing to a slower rate of hepatic metabolism.181 There are few data comparing the elimination kinetics of rectally administered barbiturates.

As in the case of thiopental, rectal methohexital is rarely used for premedication any longer. For rectal premedication, a 10% solution of 25 mg/kg or a 1% solution of 15 mg/kg administered via a shortened suction catheter provides effective sedation within 10 to 15 minutes.182–184 In some cases, the sedation may be profound, resulting in airway obstruction and laryngospasm. Hence, all children should be closely monitored with a source of oxygen, suction, and a means for providing ventilatory support; rectally administered methohexital has been reported to cause apnea in children with meningomyelocele.185,186 Children chronically treated with phenobarbital or phenytoin are more resistant to the effects of rectally administered methohexital, probably because of enzyme induction.183,187

Recovery after methohexital is relatively rapid, but the time required to return to full consciousness after a 30-minute or shorter surgical procedure is slightly prolonged compared with the time needed after 5 mg/kg of intravenous thiopental for the induction of anesthesia.188

Additional disadvantages of rectal methohexital include unpredictable systemic absorption, defecation after administration, and hiccups. Contraindications to methohexital include hypersensitivity, temporal lobe epilepsy, and latent or overt porphyria.189–191 Rectal methohexital is also contraindicated in children with rectal mucosal tears or hemorrhoids because large quantities of the drug can be absorbed, resulting in respiratory or cardiac arrest.

Nonbarbiturate Sedatives

Chloral hydrate and triclofos are orally administered nonbarbiturate drugs that are used to sedate children; both have slow onset times and are relatively long acting. They are converted to trichloroethanol, which has an elimination half-life of 9 hours in toddlers (see Fig. 47-3).192 Chloral hydrate is frequently used by nonanesthesiologists to sedate children.193–195 It is rarely used by anesthesiologists because it is unreliable, has a prolonged duration of action, is unpleasant to taste, and is irritating to the skin, mucous membranes, and gastrointestinal tract. An oral dose (50 to 100 mg/kg with a total maximum dose of 2 g) is most effective when administered 1.5 to 2 hours before anesthesia (see Chapters 6 and 47). Its use in neonates is not recommended because of impaired metabolism,196,197 nor is chronic administration recommended because of the theoretical possibility of carcinogenesis.198 Children with hepatic failure may have prolonged action of chloral hydrate, and greater doses can produce significant respiratory depression in children with liver disease. Commercially prepared chloral hydrate is no longer available in the USA but a powdered form can be reconstituted by the hospital pharmacy for oral administration.

Opioids

Morphine sulfate, 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg intravenously, may be given to children with preoperative pain. It is also effective when given orally; rectal administration is not recommended owing to erratic absorption. Neonates are more sensitive to the respiratory depressant effects of morphine, and it is rarely used to premedicate that age group.199

Fentanyl was introduced in a “lollipop” delivery system known as oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC) for premedication in children in the United States but is no longer available for that indication. Its current use is to treat breakthrough cancer pain. It is nonthreatening and more readily accepted by children than other routes as a premedicant and facilitates separation from parents.200 Fentanyl is strongly lipophilic, and OTFC is readily absorbed from the buccal mucosa, with an overall bioavailability of approximately 50%.201,202 The optimal dose for premedication is 10 to 15 µg/kg with minimal desaturation and preoperative nausea.203,204 The onset of sedation is within 10 minutes, although the blood concentrations of fentanyl continue to increase for up to 20 minutes after completion. Recovery from anesthesia after a premedication of 10 to 15 µg/kg of oral fentanyl is similar to that after 2 µg/kg intravenously.203 Doses greater than 15 µg/kg are not recommended because of opioid adverse effects, particularly respiratory depression. The incidence of the opioid-associated adverse effects is increased when the interval between completion of “lollipop” and induction of anesthesia is prolonged.204–207 Ondansetron given after the induction of anesthesia does not affect the frequency of opioid-related nausea and vomiting.208 Fentanyl has also been administered nasally (1 to 2 µg/kg) but primarily after induction of anesthesia as a means of providing analgesia in children without intravenous access.209

Sufentanil is 10 times more potent than fentanyl and is administered nasally in a dose of 1.5 to 3 µg/kg. Children are usually calm and cooperative, and most separate with minimal distress from their parents.150 In a study that compared the adverse effects of nasally administered midazolam and sufentanil, midazolam caused more nasal irritation, whereas sufentanil caused more postoperative nausea and vomiting and reduced chest wall compliance. In addition, children in the sufentanil group were discharged approximately 40 minutes later than those in the midazolam group.154 The potential adverse effects and prolonged hospital stay after nasal sufentanil makes it an unpopular choice for premedication.

Tramadol is a weak µ-opioid receptor agonist whose analgesic effect is mediated via inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake and stimulation of serotonin release. Tramadol is devoid of action on platelets and does not depress respirations in the clinical dose range.210 Serum concentrations peak by 2 hours after oral dosing with clinical analgesia maintained for 6 to 9 hours. Tramadol is metabolized by CYP2D6 and is subject to variable responses based on polymorphisms of this enzyme.211 When oral tramadol (1.5 mg/kg) was given to children who had been premedicated with oral midazolam (0.5 mg/kg), it provided good analgesia after multiple dental extractions with no adverse respiratory or cardiovascular effects.212 Intravenous tramadol (1.5 mg/kg) given before induction of general anesthesia has been compared with local infiltration of 0.5% bupivacaine (0.25 mL/kg) for ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks. Tramadol was as effective as the regional blocks in terms of pain control, although the incidence of nausea and vomiting was greater in the tramadol group. Time to discharge was similar in both groups.213

Butorphanol is a synthetic opioid agonist-antagonist with properties similar to those of morphine that can be administered nasally.214 It is as effective as equipotent doses of intramuscular meperidine and morphine, with an onset of analgesic action in about 15 minutes and peak activity within 1 to 2 hours in adults. The most frequent adverse effect is sedation that resolves approximately 1 hour after administration. A dose of 0.025 mg/kg administered nasally immediately after the induction of anesthesia was shown to provide good analgesia after myringotomy and tube placement at the expense of an increased incidence of emesis at home compared with nonopioid analgesics such as acetaminophen.215

When fentanyl or other opioids are combined with midazolam, they produce more respiratory depression than opioids or midazolam alone.216 If opioids are used in combination with other sedatives such as benzodiazepines, the dose of each drug should be appropriately reduced to avoid serious respiratory depression. For example, if fentanyl is indicated to control pain in a child who has already received midazolam, the fentanyl dose should be titrated in small increments (0.25 to 0.5 µg/kg) to prevent hypoxemia and hypopnea or apnea.

Codeine is a commonly prescribed oral opioid that must undergo O-demethylation in the liver to produce morphine to provide effective analgesia. Between 5% and 10% of children lack the cytochrome isoenzyme (CYP2D6) required for this conversion and therefore do not derive analgesic benefit. On the other hand, a very small percentage of children are ultrarapid metabolizers who rapidly convert this prodrug to morphine (see Chapter 6 for further discussion). As a result, they may experience the more severe adverse effects and complications associated with morphine (the codeine metabolite) in addition to analgesia, particularly if excessive or frequent doses of codeine are prescribed. If these same children have been sensitized to opioids because of intermittent or chronic hypoxia, the adverse events may result in respiratory and cardiac arrest.217

Codeine can be administered orally or intramuscularly but should not be administered intravenously because of the risk of seizures.217a The usual oral dose of oral codeine is 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg with an onset of action within 20 minutes and a peak effect between 1 and 2 hours. The elimination half-life of codeine is 2.5 to 3 hours. The combination of codeine with acetaminophen is effective in relieving mild to moderate pain. This combination was found to provide superior analgesia compared with acetaminophen alone after myringotomy and placement of pressure-equalizing tubes.218,219 Codeine, like all opioids, may result in nausea and vomiting (see Chapter 6).

Ketamine

Ketamine is a phencyclidine derivative that produces dissociation of the cortex from the limbic system, producing reliable sedation and analgesia while preserving upper airway muscular tone and respiratory drive.218 Ketamine may be administered by intravenous, intramuscular, oral, nasal transmucosal, and rectal routes. The disadvantages of ketamine include sialorrhea, nystagmus, an increased incidence of postoperative emesis, and possible undesirable psychological reactions such as hallucinations, nightmares, and delirium, although to date no psychological reactions have been reported after oral ketamine. Concomitant administration of midazolam may eliminate or attenuate these emergence reactions.220,221 The addition of atropine or glycopyrrolate is recommended to decrease the sialorrhea caused by ketamine.222

Intramuscular ketamine is an effective means of sedating combative, apprehensive, or developmentally delayed children who are otherwise uncooperative and refuse oral medication. A low dose of 2 mg/kg is sufficient to adequately calm most uncooperative children in 3 to 5 minutes so that they will accept a mask for inhalation induction of anesthesia and does not prolong hospital discharge times even after brief procedures.110 However, the combination of intramuscular ketamine (2 mg/kg) and midazolam (0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg) significantly prolongs recovery and discharge times, making the ketamine-midazolam combination inappropriate for brief ambulatory procedures.223

Larger doses of intramuscular ketamine are particularly useful for the induction of anesthesia in children in whom there is a desire to maintain a stable blood pressure and in whom there is no venous access, such as those with congenital heart disease. Larger doses (4 to 5 mg/kg) sedate children within 2 to 4 minutes, and very large doses (10 mg/kg) induce deep sedation that may last from 12 to 25 minutes. Larger doses and repeated doses may be associated with hallucinations, nightmares, vomiting, and unpleasant, as well as prolonged, recovery from anesthesia.110,224 Concentrations of ketamine of 100 mg/mL are available in the United States and several other countries for intramuscular injection. It is imperative to label these syringes to avoid a syringe swap with syringes containing more dilute concentrations of ketamine. Oral ketamine alone and in combination with oral midazolam is an effective premedication and has been used to alleviate the distress of invasive procedures (e.g., bone marrow aspiration) in pediatric oncology patients.225,226 In a dose of 5 to 6 mg/kg, oral ketamine alone sedates most children within 12 minutes and provides sufficient sedation in more than half of the children to permit establishing intravenous access.223,227 A larger dose of 8 mg/kg prolongs recovery from anesthesia, although by 2 hours the recovery was no different from that after 4 mg/kg.228 Doses of up to 10 mg/kg have been described as a premedicant for children having procedures for burns; the relative bioavailability was 45%, and absorption was slow with an absorption half-life of 1 hour in this cohort.229

The combination of oral midazolam and ketamine provides more effective preoperative sedation than either drug alone. This oral lytic cocktail is a good alternative for children who were not adequately sedated with oral midazolam alone. The combination of oral ketamine (3 mg/kg) and midazolam (0.5 mg/kg) did not prolong recovery after surgical procedures that lasted more than 30 minutes.230

Nasal transmucosal ketamine in a dose of 6 mg/kg is also an effective premedication for children, with sedation developing by 20 to 40 minutes.231 In theory, nasally administered ketamine could cause neural tissue damage if it reaches the cribriform plate (see E-Fig. 4-2). Because the preservative in ketamine is neurotoxic, preservative-free ketamine may be safer to administer by the nasal route, although this has not been established.232 If ketamine is given by this route, we recommend the 100 mg/mL concentration to minimize the volume that must be instilled.

Rectal ketamine (5 mg/kg) produces good anxiolysis and sedation within 30 minutes of administration.233 However, the rectal route does not provide reliable absorption.

α2-Agonists

Clonidine, an α2-agonist, causes dose-related sedation by its effect in the locus ceruleus.234 After oral administration, the plasma concentration peaks at approximately 60 minutes,235 similar to rectal administration, which peaks at about 50 minutes.236 An oral dose of 3 µg/kg given 45 to 120 minutes before surgery produces comparable sedation to that of diazepam or midazolam.237 Oral clonidine combined with 0.15 mL/kg of apple juice 100 minutes before the induction of anesthesia does not affect the gastric fluid pH and volume in children.238 Clonidine acts both centrally and peripherally to reduce blood pressure, and therefore it attenuates the hemodynamic response to intubation.239 It appears to be devoid of respiratory depressant properties, even when administered in an overdose.234 The sedative and CNS properties of clonidine reduce the dose of intravenous barbiturate required for induction of anesthesia239 as well as the minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) of sevoflurane for tracheal intubation240 and the concentration of inhaled anesthetic required for the maintenance of anesthesia, as evidenced by the hemodynamic stability.241–243 Oral clonidine (2 or 4 µg/kg) reduces MAC for tracheal extubation (MAC-ex) for sevoflurane by 36% and 60%, respectively. These doses neither prolonged emergence from anesthesia nor led to airway-related complications.244

During the first 12 hours after surgery, oral clonidine (4 µg/kg) reduced the postoperative pain scores and the requirement for supplementary analgesics.245,246 In children scheduled for tonsillectomy, those who received oral clonidine (4 µg/kg) exhibited more intense anxiety on separation and during induction than those who received oral midazolam (0.5 mg/kg). However, those who received clonidine had reduced mean intraoperative blood pressures; reduced duration of surgery, anesthesia, and emergence; and decreased need for supplemental oxygen during recovery but greater postoperative opioid requirements, greater pain scores, and greater excitement. Parenthetically, these observations are not consistent with previously reported analgesic and anesthetic properties of clonidine. Even though discharge readiness, postoperative emesis, and 24-hour analgesic requirements were similar in both groups, midazolam was judged to be the better premedicant for children undergoing tonsillectomy.247 Oral clonidine (4 µg/kg) reduces the incidence of vomiting after strabismus surgery compared with a placebo, clonidine (2 µg/kg), and oral diazepam (0.4 mg/kg).248

Although oral clonidine offers several desirable qualities as a premedication, particularly sedation and analgesia, the need to administer it 60 minutes before induction of anesthesia makes its use impractical in many busy outpatient settings.247 One study found that an oral dose of 4 µg/kg attenuated the hyperglycemic response to a glucose infusion and the surgical stress in children undergoing minor surgery, possibly by inhibiting the surgical stress release of catecholamines and cortisol. Children who were involved in surgeries that lasted 1.7 hours did not develop hypoglycemia, but in the absence of intraoperative glucose infusions, there is a risk of hypoglycemia during operations of prolonged duration.249

Dexmedetomidine is a sedative with properties that are similar to those of clonidine except that it has an eightfold greater affinity for the α2-adenoreceptors than clonidine. Based on bioavailability studies in adults,250 it is well absorbed through the oral mucosa. In a study of 13 children aged 4 to 14 years, of whom 9 had neurobehavioral disorders, an oral dose of 2 µg/kg of dexmedetomidine provided adequate sedation for a mask induction within 20 to 30 minutes of administration. It was postulated that a larger dose of 3 to 4 µg/kg might be more effective.251

Intranasal administration of 1 and 1.5 µg/kg dexmedetomidine produced significant sedation after 45 minutes with a peak effect at 90 to 150 minutes as compared with placebo. In addition, decreases in systolic blood pressure and heart rate were reported.252

In children with burns, both 2 µg/kg intranasal dexmedetomidine and 0.5 mg/kg oral midazolam administered 30 to 45 minutes before induction of anesthesia provided adequate conditions for induction of anesthesia and emergence, although dexmedetomidine produced more sleep preoperatively.253 Oral midazolam (0.5 µg/kg given 30 minutes before surgery), oral clonidine (4 µg/kg given 90 minutes before surgery), and transmucosal dexmedetomidine (1 µg/kg given 45 minutes before surgery) all produced similar preanesthetic sedation and response to separation from parents in a comparative trial, although children who received dexmedetomidine and clonidine experienced attenuated mean arterial pressure and heart rate preoperatively and reduced pain scores postoperatively compared with midazolam.254

Antihistamines

Hydroxyzine is mainly administered for its tranquilizing properties255,256; it also has antiemetic, antihistaminic, and antispasmodic properties, with minimal respiratory and circulatory effects. It is commonly administered with other classes of drugs as an intramuscular “cocktail” in a dose of 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg.

Diphenhydramine is an H1 blocker with mild sedative and antimuscarinic effects. The dose in children is 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/day (maximum 300 mg/day) in four divided doses orally, intravenously, or intramuscularly. Although the duration of action is 4 to 6 hours, it does not appear to interfere with recovery from anesthesia.257 The combination of oral diphenhydramine (1.25 mg/kg) and oral midazolam (0.5 mg/kg) has been used to provide sedation for healthy children undergoing MRI.258 The combination was more effective than midazolam alone without a delay in discharge and recovery times.

Anticholinergic Drugs

The recommended doses of anticholinergics are atropine, 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg, and scopolamine, 0.005 to 0.010 mg/kg. Atropine is more commonly used and blocks the vagus nerve more effectively than scopolamine, whereas scopolamine is a better sedative, antisialagogue, and amnestic. Infants who are at risk for or show early evidence of a slowing of the heart rate should receive the atropine before the heart rate actually decreases to ensure a prompt onset of effect to maintain cardiac output.259 Glycopyrrolate is a synthetic quaternary ammonium compound that does not cross the blood-brain barrier. It is twice as potent as atropine in decreasing the volume of oral secretions, and its duration of effect is three times greater. The recommended dose of glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg/kg) is half that of atropine. The routine use of an anticholinergic drug for the sole purpose of drying secretions is probably unwarranted, because a dry mouth can be a source of extreme discomfort for a child. Therefore, it is best to reserve the use of glycopyrrolate for specific indications such as to limit sialorrhea associated with ketamine.

Topical Anesthetics

EMLA cream (eutectic mixture of local anesthetic, Astra Zeneca, Wilmington, Del.) is a mixture of two local anesthetics (2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine). One-hour application of EMLA cream to intact skin with an occlusive dressing provides adequate topical anesthesia260 for a variety of superficial procedures, including intravenous catheter insertion, lumbar puncture, vaccination, laser treatment of port-wine stains, and neonatal circumcision.261–266 However, EMLA causes venoconstriction and skin blanching, both of which obscure superficial veins, making intravenous cannulation more difficult.267 The prilocaine in EMLA may cause methemoglobinemia,268 although, a 1-hour application at a maximum dose of 1 gram did not induce methemoglobinemia when applied to intact skin in full-term neonates and infants younger than 3 months of age.269 Lidocaine toxicity has been reported when EMLA was applied to mucosal membranes for extended periods.270

ELA-Max (4% lidocaine) is another topical anesthetic cream that decreases the pain associated with dermatologic procedures271 and intravenous catheter insertion after only a 30-minute application.272 ELA-Max causes some blanching of the skin, like EMLA cream but to a lesser extent, and dilates the veins better than EMLA cream.273

The S-Caine Patch (ZARS, Inc., Salt Lake City) is a eutectic mixture of lidocaine and tetracaine (70 mg of each per patch) that uses a controlled heating system to accelerate delivery and effectiveness of the local anesthetic. After 20 minutes of application, the pain associated with venipuncture is reduced. This patch causes mild and transient local erythema and edema and no blanching of the skin.274 Other noninvasive topical anesthetic delivery systems are available, such as lidocaine iontophoresis using an impregnated electrode, a current generator, and a return pad to carry ionized lidocaine through the stratum corneum.275 This technique provides similar pain relief for insertion of intravenous catheters in children as EMLA cream but requires extra equipment and training for proper application.276 Lidocaine iontophoresis also causes a stinging pain that some children experience during current application, and potential skin burns from the electrodes.277 Needle-free injection systems for lidocaine are also available for pain free insertion of intravenous cannulae or other needle-based procedures.277a,277b

Nonopioid Analgesics

The oral doses of acetaminophen for antipyresis,10 to 15 mg/kg, are as effective as ketorolac, 1 mg/kg,278 given 10 or more minutes postoperatively for myringotomies and tube placement.279 Oral acetaminophen is very rapidly absorbed with a bioavailability of 0.9-1.279 Neonates may have a lower incidence of hepatotoxicity because the immature hepatic enzyme systems in neonates produce less toxic metabolites than in older children.280–282 When given preemptively, acetaminophen has opioid-sparing properties that enhance analgesia in children after tonsillectomy.283,284 Preoperative oral acetaminophen and codeine provided superior analgesia to acetaminophen alone after myringotomy and tube placement.219 However, in children undergoing tonsillectomy, there was no difference in the level of pain control provided by acetaminophen and acetaminophen with codeine. Postoperative oral intake was significantly higher in children treated with acetaminophen alone.285 A relationship between concentration and analgesic effect for pain relief after tonsillectomy has been observed in children. An effect compartment concentration of 10 mg/L was associated with a reduction of pain by 2.6 units (using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 10).286

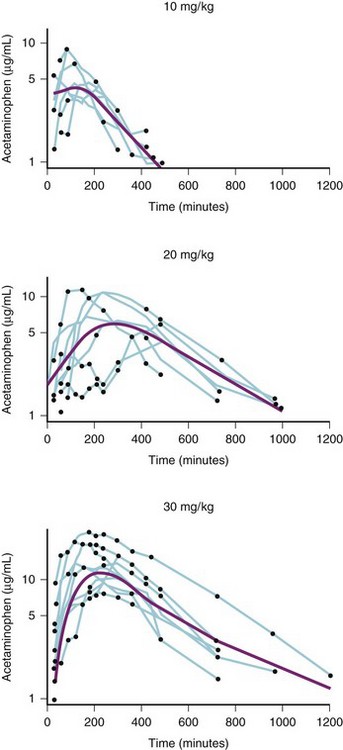

The time to the peak blood concentration of acetaminophen after rectal administration of 10, 20, and 30 mg/kg ranges between 60 and 180 minutes after administration. In addition, the equilibration half-time between plasma and effect compartment is approximately 1 hour.286 This slow absorption and delayed effect site concentrations require acetaminophen administration immediately after induction of anesthesia to provide sufficient time to achieve therapeutic blood concentrations by the end of surgery (primarily for operations that will take 1 hour or longer).287 Furthermore, doses of 10 to 30 mg/kg rectal acetaminophen may not achieve peak or sustained blood concentrations that ensure effect (Fig. 4-2). Thus, an initial dose of rectal acetaminophen of 40 mg/kg has been recommended, followed by 20 mg/kg rectally every 6 hours. This dosing regimen was subsequently confirmed.288 After 45 mg/kg rectal acetaminophen, the mean maximum blood concentration was 13 µg/mL (range 7 to 19), and the mean time to that maximum concentration was approximately 200 minutes.289 Several other single-dose rectal administration studies reported similar results.289,290

For children undergoing tonsillectomy, a preoperative oral dose of 40 mg/kg plus 20 mg/kg rectally 2 hours later was associated with satisfactory pain scores for about 8 hours after administration.279 With doses of 40 to 60 mg/kg rectally administered after induction of anesthesia but before surgery, children required less rescue morphine postoperatively and less analgesia at home than children who received either a placebo or 20 mg/kg of acetaminophen rectally.284 In addition, the children who received larger doses of acetaminophen experienced less postoperative nausea and vomiting. However, until further safety data are developed, the initial dose of acetaminophen should not exceed 40 to 45 mg/kg with a total 24-hour dose of not more than 100 mg/kg in order to avoid hepatic toxicity. Acetaminophen administered rectally in a loading dose of 40 mg/kg and then 20 mg/kg either orally or rectally every 6 hours after elective craniofacial surgery yielded greater plasma concentrations and lower pain scores than those who received oral acetaminophen; this was in part related to some children vomiting the oral acetaminophen.291 Note that these are excessive oral doses which cannot be recommended.

Excessive fasting, a very large loading dose of acetaminophen, and sevoflurane anesthesia may deplete glutathione stores and thus contribute to the development of hepatic failure.292 The coadministration of antiepileptic drugs has also been implicated in hepatotoxicity from acetaminophen.293 Because hepatic toxicity is a real and potentially fatal complication of an acetaminophen overdose, a complete medication history of acetaminophen consumption and concomitant drugs should be completed preoperatively, and the recommended maximum daily dose should not be exceeded.