17

Preoperative Assessment and Premedication

The overall aims of preoperative assessment should include the following:

To enable the most appropriate treatment for the patient, taking into consideration the patient’s current health, the nature of the proposed surgery and anaesthetic technique, and the skills and expertise of the anaesthetist.

To enable the most appropriate treatment for the patient, taking into consideration the patient’s current health, the nature of the proposed surgery and anaesthetic technique, and the skills and expertise of the anaesthetist.

To confirm that the surgery proposed is realistic and allow assessment of the likely benefit to the patient and the possible risks involved.

To confirm that the surgery proposed is realistic and allow assessment of the likely benefit to the patient and the possible risks involved.

To anticipate potential problems and ensure that adequate facilities and appropriately trained staff are available to provide satisfactory perioperative care.

To anticipate potential problems and ensure that adequate facilities and appropriately trained staff are available to provide satisfactory perioperative care.

To ensure that the patient is prepared correctly for the operation and allow time for further investigations and specialist referral to improve any existing factors which may increase the risk of an adverse outcome.

To ensure that the patient is prepared correctly for the operation and allow time for further investigations and specialist referral to improve any existing factors which may increase the risk of an adverse outcome.

To provide appropriate information to the patient, and obtain informed consent for surgery and the planned anaesthetic technique.

To provide appropriate information to the patient, and obtain informed consent for surgery and the planned anaesthetic technique.

To prescribe premedication and/or other specific prophylactic measures if required.

To prescribe premedication and/or other specific prophylactic measures if required.

To ensure that proper documentation is made of the assessment process.

To ensure that proper documentation is made of the assessment process.

THE PROCESS OF PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

History

Direct questions should be asked about the following items of specific relevance to anaesthesia.

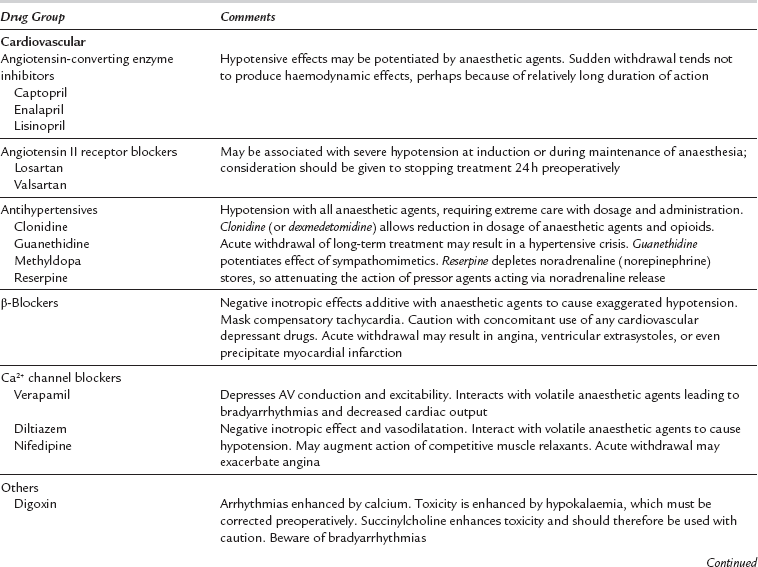

Drug History

A complete history of concurrent medication must be documented carefully. Many drugs interact with agents or techniques used during anaesthesia but problems may occur if drugs are withdrawn suddenly during the perioperative period (Table 17.1). Knowledge of pharmacology is essential to permit the anaesthetist to adjust the doses of anaesthetic agents appropriately and to avoid possibly dangerous interactions. In addition, the anaesthetist must maintain up-to-date knowledge of pharmacological advances as new drugs continue to emerge on the market. Any potential interactions observed with new drugs must always be reported to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulator Agency (MHRA), or comparable body outside the UK.

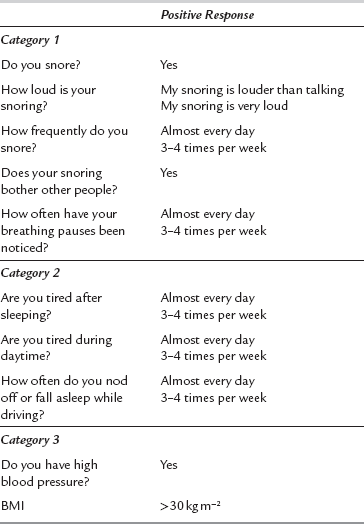

Obstructive Sleep Apnoea

Patients with obstructive sleep apnoea have a higher incidence of difficult airway management and current recommendations are that they should have careful observation in the postoperative period. The gold standard for diagnosis is polysomnography. However, this is not always available and current guidance supports the use of screening tools such as the Berlin or STOP–BANG questionnaires (Tables 17.2a and 17.2b).

TABLE 17.2a

High likelihood of obstructive sleep apnoea is indicated by 2 or more positive categories.

Category 1 is positive with ≥ 2 positive responses.

TABLE 17.2b

S: Do you snore loudly (louder than talking or loud enough to be heard through closed doors)?

T: Do you often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during daytime?

O: Has anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep?

P: Do you have or are you being treated for high blood pressure?

STOP (alone): High risk of OSA: Yes to ≥ 2 questions out of 4.

BMI: > 35 kg m− 2

Age: > 50 years

Neck circumference: > 40 cm

Gender: Male

STOP–BANG: High risk of OSA: Yes to ≥ 3 questions from 8 questions of STOP–BANG

Physical Examination

A physical examination should be performed on every patient admitted for surgery and the findings documented in the medical notes. It might be argued that this is unnecessary in young healthy patients undergoing short or minor procedures. However, the exercise is a simple and safe method for confirming good health or otherwise, and provides important information in case unexpected morbidity arises postoperatively, e.g. foot drop as a result of incorrect positioning on the operating theatre table, prolonged sensory anaesthesia following local anaesthetic techniques, etc. The information obtained from clinical examination should complement the patient’s history and allows the anaesthetist to focus further on features of relevance (Table 17.3).

TABLE 17.3

Features of the Clinical Examination Relevant to the Anaesthetist

| System | Features of Interest |

| General | Nutritional state, fluid balance |

| Condition of the skin and mucous membranes (anaemia, perfusion, jaundice) | |

| Temperature | |

| Cardiovascular | Peripheral pulse (rate, rhythm, volume) |

| Arterial pressure | |

| Heart sounds | |

| Carotid bruits | |

| Dependent oedema | |

| Respiratory | Central vs. peripheral cyanosis |

| Observation of dyspnoea | |

| Auscultation of lung fields | |

| Airway | Mouth opening |

| Neck movements | |

| Thyromental distance | |

| Dentition | |

| Nervous | Any dysfunction of the special senses, other cranial nerves, or peripheral motor and sensory nerves |

In addition, the anaesthetist must assess the patient for any potential difficulty in maintaining the airway during general anaesthesia. The teeth should be inspected closely for the presence of caries, caps, loose teeth and particularly protruding upper incisors. The extent of mouth opening is assessed, together with the degree of flexion of the cervical spine and extension of the atlanto-occipital joint. The thyromental distance should also be documented. Specific features associated with difficulty in performing tracheal intubation are described elsewhere (Ch 22).

Special Investigations

Will this investigation yield information not revealed by clinical assessment?

Will this investigation yield information not revealed by clinical assessment?

Will the results of the investigation give additional information on diagnosis or prognosis relevant to planned surgery?

Will the results of the investigation give additional information on diagnosis or prognosis relevant to planned surgery?

Will the results of the investigation alter the management of the patient?

Will the results of the investigation alter the management of the patient?

In order to reduce the volume of routine preoperative investigations, the following suggestions are made. It should be noted that these are guidelines only and should be modified according to the assessment obtained from the history and clinical examination (Table 17.4). Attention should be paid to ensuring that the results of any investigations requested are seen by the surgical team and properly documented, and that this process is undertaken in a timely manner to allow any necessary intervention with the patient’s management to be considered and implemented. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in the UK has produced a comprehensive summary of suggested testing approaches based on the patient and nature of surgery. The European Society of Anaesthesiology has also adopted these recommendations.

TABLE 17.4

Guidelines for Preoperative Investigations

| Urinalysis | All patients |

| Full blood count | All female adults |

| Before surgery which is likely to result in significant blood loss | |

| When indicated clinically, e.g. history of blood loss, previous anaemia or haemopoietic disease, cardiovascular disease, malnutrition, etc. | |

| Urea, creatinine and electrolytes | All patients over 65 years (increased likelihood of CVS disease), or with a positive urinalysis result |

| Any patient with cardiopulmonary disease, or taking cardiovascular active medication, diuretics or corticosteroids | |

| Patients with renal or liver disease, diabetes or abnormal nutritional status | |

| Patients with a history of diarrhoea, vomiting or metabolic disorder | |

| Patients receiving intravenous fluid therapy for greater than 24 h | |

| Blood glucose | Patients with diabetes mellitus, vascular disease or taking corticosteroids |

| Liver function tests | Any history of liver disease, alcoholism, previous hepatitis or an abnormal nutritional state |

| Coagulation screen | Any history of a coagulation disorder, drug abuse, significant chronic alcohol abuse, acute or chronic liver disease or anticoagulant medication |

| ECG | Male smokers older than 45 years; all others older than 50 years |

| Any history (actual or suspected) of heart disease or hypertension | |

| Any patient taking medication active on the cardiovascular system or a diuretic | |

| Patients with chronic or acute-on-chronic pulmonary disease | |

| Chest X-ray | Rarely indicated unless active cardiac or respiratory disease or possible pulmonary metastases. |

| Previously abnormal chest X-ray is not an indication in its own right to repeat a chest X-ray |

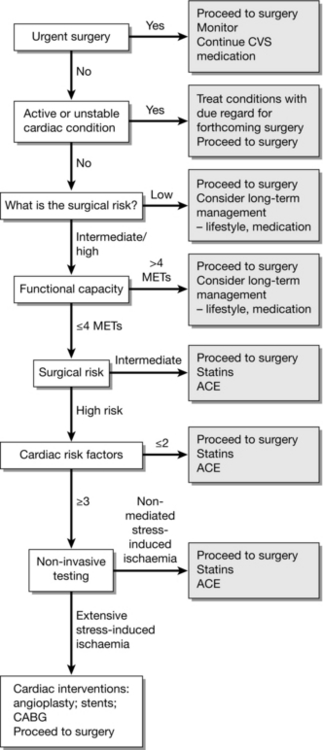

Cardiac Investigation

The extent of cardiac investigation should be based on the urgency of surgery, the presence of active cardiac conditions which require treatment, the risk of complications from surgery and the patient’s physical fitness. A schematic of an approach to patients at risk of cardiac events is shown in Figure 17.1.

FIGURE 17.1 Approach to investigation of patients at risk of cardiac complications. Simplified from European and American Guidelines.

METs: metabolic equivalents – inability to climb two flights of stairs or run a short distance equates to < 4 METs.

Cardiac risk factors:

➢ Stroke/transient ischaemic attack

➢ Renal dysfunction (serum creatinine > 170 mmol L− 1 or 2 mg dL− 1 or a creatinine clearance of < 60 mL min− 1)

Surgical risk of MI and cardiac death within 30 days after surgery

| Low risk (< 1%) | Intermediate risk (1–5%) | High risk (> 5%) |

| Breast Dental Endocrine Eye Gynaecology Reconstructive Orthopaedic – minor Urology – minor |

Abdominal Carotid surgery Peripheral angioplasty Endovascular aneurysm repair Head and neck Neurological Orthopaedic – major Transplant Urology – major |

Aortic/major vascular Peripheral vascular |

ECG

A 12-lead electrocardiogram can demonstrate many acute or longstanding pathological conditions affecting the heart, particularly changes in rhythm or the occurrence of myocardial ischaemia or infarction. It has little value as a preoperative baseline in patients with known or potential cardiovascular disease; in the resting state, the trace may appear normal despite the presence of clinically significant coronary artery disease. More extensive investigations are available in many departments to supplement the 12-lead ECG and these are discussed elsewhere (see Chs 18 and 34).

PREDICTION OF PERIOPERATIVE MORBIDITY OR MORTALITY

Is the patient in optimum physical condition for anaesthesia and surgery?

Is the patient in optimum physical condition for anaesthesia and surgery?

Are the anticipated benefits of surgery greater than the combined risks of undergoing anaesthesia and surgery, taking into account any concurrent disease?

Are the anticipated benefits of surgery greater than the combined risks of undergoing anaesthesia and surgery, taking into account any concurrent disease?

general scoring systems designed to predict nonspecific undesirable events

general scoring systems designed to predict nonspecific undesirable events

systems which focus on prediction of specific morbidity or technical difficulty, e.g. adverse cardiac events, difficulty with tracheal intubation.

systems which focus on prediction of specific morbidity or technical difficulty, e.g. adverse cardiac events, difficulty with tracheal intubation.

Prediction of Non-Specific Adverse Outcome

Any prospective studies intended to evaluate predictive factors of perioperative risk rely upon the incorporation of large numbers of patients and scrupulous design. Those that have been published tend to agree on several factors identified from physiological, demographic and laboratory data which can combine to indicate the likelihood of adverse outcome (Table 17.5).

TABLE 17.5

Typical Preoperative Features which may Increase the Likelihood of Significant Perioperative Complications or Mortality

| Demographic/Surgical | Pathophysiological | Laboratory |

| Age > 70 years | Dyspnoea at rest or on minimal exertion | Serum urea > 20 mmol L–1 |

| Major thoracic, abdominal or cardiovascular surgery | MI within 30 days or unstable angina, untreated heart failure or high grade arrhythmias | Serum albumin < 30 g L–1 |

| Perforated viscus (excluding appendix), pancreatitis or intraperitoneal abscess | Cardiac symptoms requiring medical treatment | Haemoglobin < 10 g dL–1 |

| Intestinal obstruction | Confusional state | |

| Palliative surgery | Clinical jaundice | |

| Smoking | Significant weight loss (> 10%) in 1 month | |

| Cytotoxic or corticosteroid treatment | Productive cough with sputum, especially if persistent | |

| Controlled diabetes | Haemorrhage or anaemia requiring transfusion |

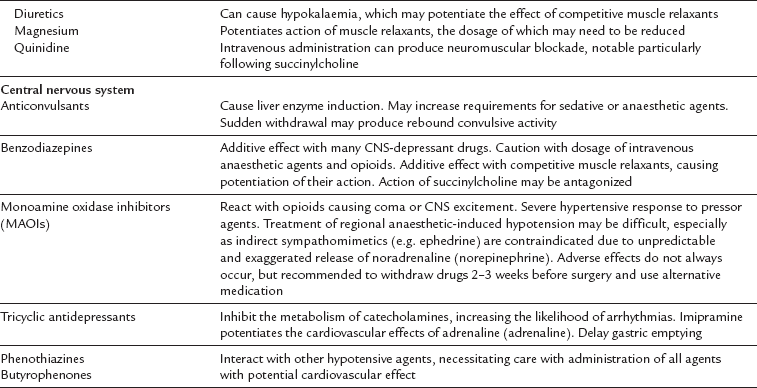

ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) Grading

The ASA grading system (Table 17.6) was introduced in the 1960s as a simple description of the physical state of a patient, along with an indication of whether surgery is elective or emergency. Despite its apparent simplicity, it remains one of the few prospective descriptions of the patient which correlates with the risks of anaesthesia and surgery. However, it does not embrace all aspects of anaesthetic risk, as there is no allowance for inclusion of many criteria such as age or difficulty in intubation. In addition, it does not take into account the severity of either the presenting disease or the surgery proposed, nor does it identify factors which can be improved preoperatively in order to influence outcome. Nevertheless, it is extremely useful and should be applied to all patients who present for anaesthesia.

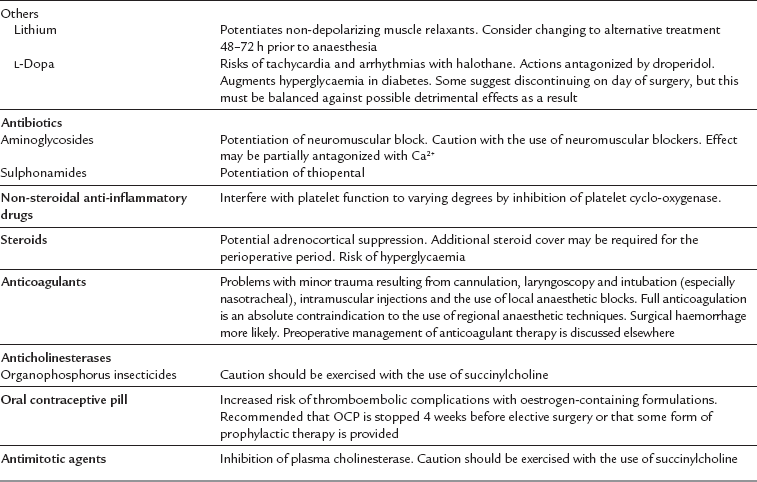

POSSUM

This stands for ‘Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity’. First reported in 1991, this tool was developed to compare mortality and morbidity over a wide range of general surgical procedures, and takes into account 12 physiological and six operative factors which are either readily available or predictable in the immediate preoperative period (Table 17.7). These factors are weighted according to their value, and a logistic regression formula applied to calculate ‘risk’ of mortality or morbidity. Some groups have modified the formula (P-POSSUM) after suggestions that the original system overestimated the risk of death in low-risk patient groups, and others have produced speciality-specific variants (e.g. V-POSSUM for elective vascular surgery). It should be emphasized that the POSSUM scoring system was designed to compare observed with expected death rates among populations rather than to predict mortality for an individual, and should be applied only in this way.

TABLE 17.7

Factors Contributing to the POSSUM Score for Risk of Perioperative Mortality and Morbidity. A Higher Score is Awarded for Increasing Deviation from the ‘Normal’ Value or Range

| Physiological Factors | Operative Factors |

| Age (years) | Operative complexity |

| Cardiac status | Single vs. multiple procedures |

| Respiratory status | Expected blood loss |

| Systolic blood pressure | Peritoneal contamination (blood, pus, bowel content) |

| Pulse rate | Extent of any malignant spread |

| Glasgow Coma Score | Urgency of surgery |

| Haemoglobin concentration | |

| White cell count | |

| Serum urea concentration | |

| Serum sodium concentration | |

| Serum potassium concentration | |

| ECG rhythm |

Prediction of Specific Adverse Events

There are specific medical or surgical conditions which are associated with potential airway problems during anaesthesia, such as obesity, the later stages of pregnancy, a large neck, mediastinal tumours and some faciomaxillary deformities. Apart from these, it requires an experienced anaesthetist to collate various physical features which can predict likely difficulty. Several classifications or scoring systems have been designed for this purpose, although none is entirely reliable; they are discussed elsewhere (see Chs 21 and 22).

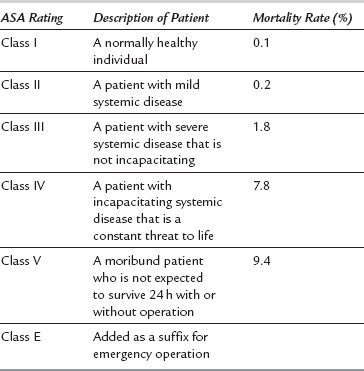

Adverse Cardiac Events

Over 25 years ago, Goldman and colleagues published a retrospective analysis of preoperative risk factors which were associated with an adverse cardiac event following non-cardiac surgery. This topic has been re-evaluated extensively in the intervening years, with many studies agreeing broadly with Goldman’s conclusions. However, conflicting opinions exist regarding identification of the most accurate predictors, probably as a result of the diversity of methods used in these studies together with the significant and continued advances made in the understanding and management of cardiovascular pathophysiology. The most widely used risk index currently is Lee’s Revised Cardiac Risk Index (Table 17.8).

TABLE 17.8

Lee’s Revised Cardiac Risk Index

| Indicators | |

| High risk surgical procedures | Intraperitoneal Intrathoracic Suprainguinal vascular |

| History of ischaemic heart disease | History of myocardial infarction History of positive exercise test Current ischaemic chest pain Use of nitrate therapy ECG with pathological Q waves |

| Congestive heart failure | History of congestive heart failure, pulmonary oedema or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea Physical examination showing bilateral rales or S3 gallop Chest X-ray showing pulmonary vascular redistribution |

| Cerebrovascular disease | History of transient ischaemic attack or stroke |

Reprinted from Thomas H. Lee, Edward R. Marcantonio, Carol M. Mangione et al. Derivation and Prospective Validation of a Simple Index for Prediction of Cardiac Risk of Major Noncardiac Surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:1043–1049.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Postponing Surgery for Clinical Reasons

Emergency Surgery for Which the Patient has not been Resuscitated Adequately

Surgery for haemorrhage control in trauma is discussed elsewhere (see Ch 37).

Preoperative Fasting

There are many factors which can increase the likelihood of significant gastric content regardless of the period of starvation (e.g. pain, anxiety, some drugs and premedication including opioid analgesics, paralytic ileus, later stages of pregnancy, etc.).

There are many factors which can increase the likelihood of significant gastric content regardless of the period of starvation (e.g. pain, anxiety, some drugs and premedication including opioid analgesics, paralytic ileus, later stages of pregnancy, etc.).

The normal daily secretion of gastric fluid can approach 2000 mL in adults; consequently, the stomach is never truly ‘empty’.

The normal daily secretion of gastric fluid can approach 2000 mL in adults; consequently, the stomach is never truly ‘empty’.

Clinical studies which encourage changes in practice should be scrutinized carefully to ensure that the results are not extrapolated beyond the sample of the population upon which they were based.

Clinical studies which encourage changes in practice should be scrutinized carefully to ensure that the results are not extrapolated beyond the sample of the population upon which they were based.

Providing Information to the Patient and Obtaining Consent

Consent for anaesthesia is a vital part of preoperative preparation. It is discussed more fully in Chapter 19. It must be obtained by an individual with sufficient knowledge of the procedure and the risks involved. In order for consent to be valid, it must encompass three elements:

The patient must have the capacity to consent to the treatment offered.

The patient must have the capacity to consent to the treatment offered.

The patient must have sufficient information to enable him/her to make a balanced decision to consent.

The patient must have sufficient information to enable him/her to make a balanced decision to consent.

All patients should be told of common complications associated with the proposed anaesthetic technique (e.g. succinylcholine pains, postdural puncture headache).

All patients should be told of common complications associated with the proposed anaesthetic technique (e.g. succinylcholine pains, postdural puncture headache).

All patients should be told what they may experience in the perioperative period, including temporary numbness and weakness in the postoperative period if a local or regional technique is to be used.

All patients should be told what they may experience in the perioperative period, including temporary numbness and weakness in the postoperative period if a local or regional technique is to be used.

If a technique of a sensitive nature (e.g. insertion of an analgesic suppository) is to be used during anaesthesia, the patient should be informed.

If a technique of a sensitive nature (e.g. insertion of an analgesic suppository) is to be used during anaesthesia, the patient should be informed.

Patients should be informed of any increased risk related to their preoperative condition (e.g. damage to loose or crowned teeth, or cardiac complications in the presence of severe coronary artery disease).

Patients should be informed of any increased risk related to their preoperative condition (e.g. damage to loose or crowned teeth, or cardiac complications in the presence of severe coronary artery disease).

All patients should be given the opportunity to ask questions, and specific questions relating to anaesthesia must be answered honestly; if the questions relate to surgery, then the anaesthetist should ensure that a surgeon speaks to the patient before anaesthesia is induced.

All patients should be given the opportunity to ask questions, and specific questions relating to anaesthesia must be answered honestly; if the questions relate to surgery, then the anaesthetist should ensure that a surgeon speaks to the patient before anaesthesia is induced.

A summary of the matters discussed, the risks explained and the techniques agreed should be documented on the anaesthetic record.

A summary of the matters discussed, the risks explained and the techniques agreed should be documented on the anaesthetic record.

PREMEDICATION AND OTHER PROPHYLACTIC MEASURES

reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting

reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting

assist with intra- and postoperative analgesia

assist with intra- and postoperative analgesia

Analgesia

Paracetamol: Paracetamol is a cheap and effective analgesic when given as an oral premedication. Many day-case and children’s surgery units do this as routine. Logistical reasons prevent many main theatre units from doing this, but the anaesthetist should always consider prescribing paracetamol at the preoperative visit.

Reduction in Gastric Volume and Elevation of Gastric pH

In patients who are at risk of vomiting or regurgitation (e.g. emergency patients with a full stomach or elective patients with hiatus hernia), it may be desirable to promote gastric emptying and elevate the pH of residual gastric contents. Gastric emptying may be enhanced by the administration of metoclopramide, which also possesses some antiemetic properties, while elevation of the pH of gastric contents may be produced by administration of sodium citrate. This topic is described in greater detail in Chapter 37.

Reduction in Vagal Reflexes

Traction of the eye muscles, particularly the rectus medialis, during squint surgery may result in bradycardia and/or arrhythmias (the oculocardiac reflex). Premedication with atropine protects against this but it is not as effective as the intravenous administration of atropine at induction of anaesthesia or in anticipation of traction of the muscles.

Traction of the eye muscles, particularly the rectus medialis, during squint surgery may result in bradycardia and/or arrhythmias (the oculocardiac reflex). Premedication with atropine protects against this but it is not as effective as the intravenous administration of atropine at induction of anaesthesia or in anticipation of traction of the muscles.

Repeated administration of succinylcholine often results in bradycardia, which sometimes proceeds to asystole. Administration of atropine should always precede the administration of a second dose of succinylcholine.

Repeated administration of succinylcholine often results in bradycardia, which sometimes proceeds to asystole. Administration of atropine should always precede the administration of a second dose of succinylcholine.

Surgical stimulation during a balanced anaesthetic technique may be associated with bradycardia – particularly during laparoscopy.

Surgical stimulation during a balanced anaesthetic technique may be associated with bradycardia – particularly during laparoscopy.

The administration of propofol to patients with a slow heart rate may result in dangerous degrees of bradycardia.

The administration of propofol to patients with a slow heart rate may result in dangerous degrees of bradycardia.

Drugs Used for Premedication

Anticholinergic Agents

Anticholinergic drugs are used clinically to produce the following effects:

Antisialagogue effects. Glycopyrronium and hyoscine are more potent than atropine in this respect. These drugs block secretions when irritant anaesthetic gases are used and reduce excessive secretions and bradycardia associated with succinylcholine when it is given either repeatedly or as an infusion.

Antisialagogue effects. Glycopyrronium and hyoscine are more potent than atropine in this respect. These drugs block secretions when irritant anaesthetic gases are used and reduce excessive secretions and bradycardia associated with succinylcholine when it is given either repeatedly or as an infusion.

Sedative and amnesic effects. In combination with morphine, hyoscine produces powerful sedative and amnesic effects.

Sedative and amnesic effects. In combination with morphine, hyoscine produces powerful sedative and amnesic effects.

Prevention of reflex bradycardia. Anticholinergics are given for both prophylaxis and treatment of bradycardia. Atropine is used commonly as premedication in ophthalmic surgery to block the oculocardiac reflex in patients undergoing squint surgery and has been used also in small children to reduce the bradycardia which may occur in association with halothane anaesthesia.

Prevention of reflex bradycardia. Anticholinergics are given for both prophylaxis and treatment of bradycardia. Atropine is used commonly as premedication in ophthalmic surgery to block the oculocardiac reflex in patients undergoing squint surgery and has been used also in small children to reduce the bradycardia which may occur in association with halothane anaesthesia.

Side-effects of anticholinergic drugs include the following:

CNS toxicity. The central anticholinergic syndrome is produced by stimulation of the CNS (usually by atropine). Symptoms include restlessness, agitation and somnolence and, in extreme cases, convulsions and coma. With hyoscine, there is more commonly prolonged somnolence. Physostigmine 1–2 mg i.v. has been recommended to reverse the central anticholinergic syndrome, but is no longer available in the UK. Diazepam has been reported to have a beneficial effect but the patient must be observed closely and steps taken if necessary to deal with depression of ventilation or upper airway obstruction.

CNS toxicity. The central anticholinergic syndrome is produced by stimulation of the CNS (usually by atropine). Symptoms include restlessness, agitation and somnolence and, in extreme cases, convulsions and coma. With hyoscine, there is more commonly prolonged somnolence. Physostigmine 1–2 mg i.v. has been recommended to reverse the central anticholinergic syndrome, but is no longer available in the UK. Diazepam has been reported to have a beneficial effect but the patient must be observed closely and steps taken if necessary to deal with depression of ventilation or upper airway obstruction.

Reduction in lower oesophageal sphincter tone. Theoretically, a reduction in tone may lead to an increased risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux, although in clinical practice there is no suggestion that the use of anticholinergics for premedication is associated with an increased incidence of regurgitation and aspiration.

Reduction in lower oesophageal sphincter tone. Theoretically, a reduction in tone may lead to an increased risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux, although in clinical practice there is no suggestion that the use of anticholinergics for premedication is associated with an increased incidence of regurgitation and aspiration.

Tachycardia, which should be avoided in patients with cardiac disease (e.g. obstructive cardiomyopathy, valvular stenosis or ischaemic heart disease) or when a hypotensive anaesthetic technique is planned.

Tachycardia, which should be avoided in patients with cardiac disease (e.g. obstructive cardiomyopathy, valvular stenosis or ischaemic heart disease) or when a hypotensive anaesthetic technique is planned.

Mydriasis and cycloplegia, which lead to visual impairment. This may be troublesome, but is not a serious side-effect. Theoretically, mydriasis may be associated with reduced drainage of aqueous humour from the anterior chamber of the eye, thereby increasing intraocular pressure in patients with glaucoma. However, this effect is not important in practice and atropine may be prescribed safely to patients with glaucoma provided that appropriate therapy is maintained.

Mydriasis and cycloplegia, which lead to visual impairment. This may be troublesome, but is not a serious side-effect. Theoretically, mydriasis may be associated with reduced drainage of aqueous humour from the anterior chamber of the eye, thereby increasing intraocular pressure in patients with glaucoma. However, this effect is not important in practice and atropine may be prescribed safely to patients with glaucoma provided that appropriate therapy is maintained.

Pyrexia. By suppressing secretion of sweat, anticholinergics predispose to an increase in body temperature. These drugs should therefore be avoided in the presence of pyrexia, particularly in children.

Pyrexia. By suppressing secretion of sweat, anticholinergics predispose to an increase in body temperature. These drugs should therefore be avoided in the presence of pyrexia, particularly in children.

Excessive drying. Although anticholinergics are given for the specific purpose of producing antisialagogue effects, this may be most unpleasant for the patient.

Excessive drying. Although anticholinergics are given for the specific purpose of producing antisialagogue effects, this may be most unpleasant for the patient.

Increased physiological dead space. Atropine and hyoscine increase physiological dead space by 20–25%, but this is compensated for by an increase in ventilation.

Increased physiological dead space. Atropine and hyoscine increase physiological dead space by 20–25%, but this is compensated for by an increase in ventilation.

Other Prophylactic Measures

Thought should be given to the value of giving prophylactic treatment for the specific situations summarized in Table 17.9.

TABLE 17.9

Prophylactic Measures Against Specific Complications

| Complication | Methods of Prophylaxis |

| Deep vein thrombosis | Early postoperative mobilization |

| Leg exercises (active/passive) | |

| Pneumatic compression of limbs | |

| Electrical stimulation of calf muscles | |

| Graduated stockings | |

| Low-dose subcutaneous heparin | |

| Warfarin anticoagulation | |

| (Regional anaesthetic techniques, especially for orthopaedic lower-limb procedures) | |

| Aspiration of gastric contents | Nil by mouth |

| Antacids: sodium citrate | |

| H2-antagonists | |

| Omeprazole | |

| Metoclopramide | |

| Infection | |

| Surgical procedure | Directed by local or national practice with advice of microbiologists |

| Infective endocarditis | Follow guidelines of the Endocarditis Working Party |

| Adrenocortical suppression – suggested for patients who have received exogenous systemic steroids (> 10 mg prednisolone/day) during the 2 months preceding surgery | Hydrocortisone 25 mg 6-hourly, or continue usual steroids if this is in excess of the current requirements (i.e. > 300 mg hydrocortisone equivalent, which is the maximum daily production in response to stress). Consult local guidance. |

American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. (Writing Committee to revise the 2002 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery) Developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:1971–1996.

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Pre-operative assessment: the role of the anaesthetist, 2001. www.aagbi.org

De Hert, S., Imberger, G., Carlisle, J., et al. Preoperative evaluation of the adult patient undergoing non-cardiac surgery: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:684–722.

Donati, A., Ruzzi, M., Adrario, E., et al. A new and feasible model for predicting operative risk. Br. J. Anaesth. 2004;93:393–399.

Janke, E., Chalk, V., Kinley, H. Pre-operative assessment: setting a standard through learning. University of Southampton; 2002.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. CG3 – pre-operative testing, the use of routine pre-operative tests for elective surgery, 2003. www.nice.org.uk

Pearse, R.M., Moreno, R.P., Bauer, P., et al. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1059–1065.

Poldermans, D., Bax, J.J., Boersma, E., et al. Guidelines for preoperative cardiac risk assessment and perioperative cardiac management in noncardiac surgery: the Task Force for Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Perioperative Cardiac Management in Noncardiac Surgery of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA). Eur. Heart J. 2009;30:2769–2812.

Stoelting, R.K., Diedrorf, S.F. Handbook of anesthesia and co-existing disease, fourth ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2002.