37 Prenatal and Neonatal Palliative Care

For most, pregnancy is a time filled with joyful anticipation of welcoming a new life into the family. Technological advances provide early confirmation of pregnancy, thus allowing parents to share their news with others, often just weeks after conception. Technology also permits clinicians to detect life-threatening fetal complications. Each year in the United States, more than one million pregnancies will end in fetal death, many due to genetic abnormalities. More than 26,000 babies between 20 and 40 weeks’ gestation will be stillborn, and nearly 18,000 neonates will die within the first 28 days of life, with nearly half of these deaths due to congenital diseases and/or prematurity.1 Gestational risk factors such as a family history of genetic diseases or maternal chronic illness can result in repeated losses.

Families may learn that their baby has a life-threatening fetal diagnosis early in pregnancy, in the prenatal period just prior to delivery, or in the neonatal period after birth. As parents learn of a life-threatening fetal condition, they bear the difficult task of shifting from joyful welcoming of new life to comprehending the ramifications of their baby’s diagnosis. Palliative care in each scenario is targeted to families’ unique needs after diagnosis, when families begin to grieve the loss of a “normal” pregnancy or infant.2 Fetal-neonatal conditions that would benefit from the interventions and support of palliative care can include rare syndromes such as anencephaly and Potter’s syndrome, all extremely premature infants, and infants with severe birth injuries. We will describe how interdisciplinary clinicians can deliver integrated, compassionate, and evidence-based services for these infants and families.

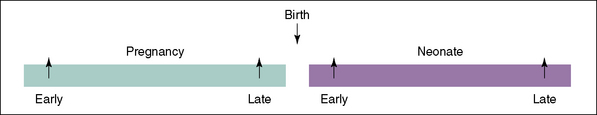

In this chapter, we discuss prenatal-neonatal palliative and end-of-life care. Often the term perinatal is used to describe care around the time of birth; we will use prenatal and neonatal to be more precise. We will highlight the unique contributions of interdisciplinary team (IDT) clinicians, as related to four distinct periods (Fig. 37-1):

IDT Clinicians and Roles

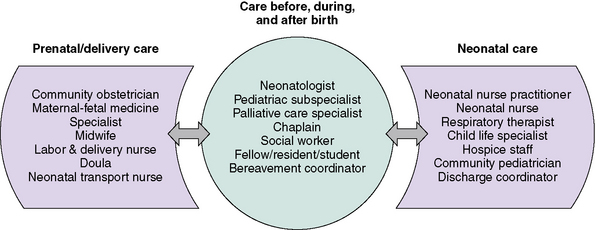

The diagnosis and management of a life-threatening condition for an infant can span the prenatal and neonatal periods, and may require the involvement of unique interdisciplinary team clinicians not found in other areas of pediatric palliative care (Fig. 37-2). Not uncommonly, IDT clinicians work in different clinics, hospitals, or even cities due to the nature of regionalized neonatal care. For example, a life-threatening fetal diagnosis may be made by a community obstetrician, with subsequent management of both mother and baby by multiple subspecialists at a large referral center. Particular effort must be made to communicate well and to provide seamless care to families throughout this trajectory of care.

Supporting families’ practical needs

Mothers with a high-risk pregnancy are often hospitalized for a prolonged period before birth. The mother’s hospitalization can profoundly disrupt the life of the family, and mothers often worry about this burden on their loved ones.3 Distance from home to the regional hospital may be significant, with the associated costs of travelling and parking. Families with a limited income may be forced to visit during late hours when parking is free, which can affect communication with daytime care providers.

Environments that are conducive to and promote family presence are essential. Privacy and lenient visitation hours are important to women hospitalized prenatally.3 When private rooms are not available, strategies are needed to maintain confidentiality during parent-provider discussions. Parents are very cognizant of and appreciative for those clinicians who go out of their way to enable family members to be present with them at their time of distress.4

Siblings may be aware of a baby’s expected arrival before the life-threatening fetal diagnosis is made. Siblings have their own feelings of anticipation, excitement, sadness, or ambivalence. IDT clinicians may need to provide families with strategies to allow siblings to maintain closeness with their mother during her hospitalization while maintaining as normal of a home routine as possible. Parents may need suggestions about how to include their children in the events surrounding the baby’s birth and death.5 Child life specialists can offer creative avenues of art, play, and interactive therapies to assist these children as they meet and say good-bye to their baby brother or sister.

Communication

The importance of clear, honest, and compassionate communication is central to prenatal and neonatal palliative care.6–9 Clinicians can convey empathy through careful listening and anticipation of the family’s needs. Respect is apparent when clinicians refer to the baby by his or her given name. Respect extends to colleagues when conflicting opinions, which often arise in prenatal and neonatal decision- making, are approached in a professional manner. A family’s confidence and trust in the healthcare team are eroded if they witness disrespectful behavior among members of the team. An example of disrespectful behavior is when clinicians are openly critical of the competency of their colleagues because of a disagreement with a medical diagnosis and/or a management decision. These conversations should never occur in the family’s presence or where the conversations could be overheard. A family needs to know that clinicians work collaboratively as a team and with the family to identify a plan of care.

Decision-making

Internationally, there is significant variation in the process of decision-making for these infants. In countries with paternalistic models of medical care, physicians decide which infants will receive life-sustaining therapies, without family input.10 In the United States, parent-provider collaboration in shared decision-making has become increasingly important. Neonatologists acknowledge that, at times, family autonomy in decision-making may even surpass the authority of the medical team.11–13 For instance, a neonatologist may not feel comfortable limiting delivery room resuscitation for an infant born at  weeks’ gestation if the family requests that “everything be done,” even when the likelihood of survival is extremely low.

weeks’ gestation if the family requests that “everything be done,” even when the likelihood of survival is extremely low.

Best practices for engaging in shared decision-making before, during, and after birth are not clear. Ideally, multiple interdisciplinary discussions would occur with families over time while minimizing the stressors of maternal illness, pain, and disruption of the family’s home life. But this rarely occurs. While data about these interactions are limited, retrospective data suggest that parent-provider collaboration in these scenarios is incomplete. A study interviewing the parents and neonatologists within 24 hours of counseling showed there was only 59% agreement that a management plan had been formulated.14

Parents and providers may come to these conversations with very different priorities. Neonatologists often emphasize predictions of morbidities and mortality,15–17 yet families often focus on emotions, hope, and religious and spiritual beliefs.18,19 Those who became pregnant through assisted reproduction or who have suffered repeated losses may be particularly committed to continuing a pregnancy, regardless of predictions of illness or death.20 Families may possess unrealistic expectations for their infant based on media portrayal of “miracle babies.”

As with older children, parents have the right to act as surrogate decision makers for their infants. But surrogate decision-making for infants is unique in several ways. The concept of prior preferences does not apply to newborns. Parents and providers may differ significantly in their perceptions of a “good” quality of life for infants; in one study, parents were more likely than providers to believe that attempts should be made to save all infants, regardless of projected outcomes.21 New parents already expecting to bring home a totally dependent infant may underestimate the consequences of decisions that may extend this dependence indefinitely.

Families must be cautioned that, once a decision is made, diagnostic and prognostic uncertainty may translate into unexpected outcomes. The family who makes a carefully detailed birth plan involving out-of-state family members and religious rituals may suffer a fetal death before birth. Families who opt for non-resuscitation of an extremely premature infant to prevent infant suffering may deliver a vigorous baby weighing 200 g more than predicted. Providers and families alike should prepare for the possibility that management decisions may need to be altered quickly based on new information.22–24

Finally, it should be noted that not all management options are equally available to families. Hospital and state policies can impact provider willingness to offer the options of pregnancy termination, non-initiation of resuscitation, and withdrawal of therapy.25,26

Hope

Redefining hope is critical during prenatal and neonatal palliative care. Families are often unprepared for the diagnosis of a potentially lethal fetal or neonatal condition. Physicians may worry that talking about hope will create unrealistic expectations, yet parents who have gone through this have emphasized that, regardless of the infant’s prognosis, parents need providers to give them hope for something.18,19,27 One study found that physicians who provided more hope to families were not necessarily more likely to predict survival, but they did express emotion and showed parents that they were touched by the tragedy of the situation.18 Adult patients with a terminal diagnosis said providers can provide hope by shifting the focus to what can be realistically achieved versus what can only be wished for.28 For the IDT that is counseling a family, this might mean openly acknowledging the grief and pain of the situation, reassuring the family that the team will join in their hope that the infant’s outcome will be a good one, and helping them to imagine how they might want events to proceed if the outcome is death or severe disability.

It is helpful to talk with families about what is meaningful to them, such as the possibility of holding a baby who is alive, or making sure that the infant does not experience pain. Hope for a good outcome may need to be redefined repeatedly over time in a way that helps families to cherish what is possible with their infant. For parents expecting multiple babies, parental hope for each of the developing fetuses in utero may hang in a delicate balance, especially if one is diagnosed with a life-threatening condition. When the death of a multiple occurs, parents must simultaneous maintain hope for the surviving babies while experiencing grief for their loss.29

Cultural, religious, and spiritual issues

Families often struggle to make meaning of a child’s death in the context of their cultural, religious, spiritual, or existential beliefs. This struggle may inform the decisions families make regarding their infant. A 2010 text30 provides an excellent reference for neonatal end-of-life care issues as related to a number of religious traditions. Several aspects of religion and prenatal and/or neonatal end-of-life care should be noted. In some traditions, a fetus is not recognized as a person until it is born alive. Parents from these traditions who experience a miscarriage or stillbirth may feel abandoned by their communities, and may need additional resources from the IDT. In other traditions, families may struggle to reconcile pregnancy termination or withdrawal of neonatal care with religious doctrine. Talking with their own religious leader and/or a hospital chaplain can be invaluable, both by alleviating family guilt and by helping the medical team to better understand the parents’ values. Obstetric and neonatal wards often limit visitors; accommodations need to be made for families’ cultural or religious end-of-life rituals. One advantage of home hospice for infants is the opportunity for families to more freely participate in religious and cultural rituals.

Professional Caregiver Suffering and Moral Distress

As in other areas of pediatric palliative care, being with families throughout their baby’s dying can be deeply rewarding but can also lead to suffering by the professional caregiver. Suffering is intensified in situations involving moral distress, which often characterizes the uncertainty of prenatal and neonatal prognosis.31 Tragic infant deaths and cumulative losses can make it difficult for a clinician to create meaning in his or her profession. clinicians who themselves are childbearing or childrearing may closely identify with families, particularly when clinicians have a long-term relationship with the family. Though such sensitivity can promote empathy in the clinician, it can also cause death anxiety and grief. A dual-process model of clinician’s grief has been described: clinicians will simultaneously experience grief reactions by focusing on the loss and avoiding grief reactions by focusing on other aspects of a patient’s care.32,33

Infant deaths often occur in environments that do not support clinicians’ needs. Prenatal deaths may occur in birth centers, where care is focused on healthy births, often evidenced by names such as the New Life Center. Clinicians in birth centers may struggle to care for bereaved families while simultaneously caring for parents who are birthing healthy infants.34 Neonatal deaths often occur in intensive care units, which rarely emphasize the sacredness of the end-of-life experience. Though clinicians may join in annual rituals to honor deceased patients and their own grief, support during acute losses may not be available.

IDT clinicians from varying disciplines have unique experiences with families at the end of life. For example, while neonatal nurses rarely feel involved in decision-making, neonatal physicians feel very responsible for end-of-life decision-making.35 These differences may make it difficult for providers to fully support each other. IDT clinicians, such as chaplains, with expertise in addressing suffering could facilitate self-care for others.

Strategies for minimizing professional caregiver suffering must also take place at the organizational level. An educational intervention in end-of-life care, which included content on prevention of compassion fatigue, has been shown to increase the comfort of neonatal nurses who care for a dying infant.36 Other strategies might include a core group of clinicians to serve as a resource on all shifts, case reviews of each death for all disciplines, engaging mental health liaisons for debriefing, and providing meaningful gestures to clinicians, such as massages. Co-creation of ritual may provide clinicians with opportunities to both support bereaved families and facilitate their own grief work33 (Fig. 37-3).

The Four Periods of Prenatal and Neonatal Palliative Care

Early prenatal palliative care

Setting

As illustrated in the case study, EPP palliative care may begin in the obstetrician’s office. Further evaluation may involve specialist consultations at a regional hospital far from the family’s home. In some instances, diagnosis of a specific prenatal condition, such as twin-to-twin transfusion or monoamniotic twins, may require the parents to travel out of state for specialized prenatal care. The emergence of hospital-based fetal care programs affords each IDT clinician the opportunity to initiate palliative care throughout the trajectory of care.37 If the baby survives past delivery and beyond the time of the mother’s discharge from the hospital, palliative and hospice care may be provided in the family’s home. Some families may opt for home birth, with care provided by a hospice and midwife team.

Interdisciplinary Team Clinicians

Parents who receive a life-threatening fetal diagnosis may interact with numerous IDT clinicians at multiple sites of care. In fact, each discipline represented in Fig. 37–2 could interact with the family throughout pregnancy, delivery, and the baby’s birth and death. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that a key point person be identified who can facilitate continuity throughout the trajectory of care. As one mother reported to the advanced practice nurse who filled such a role on the palliative care team: “You were our safe, familiar center in the middle of this frightening storm.”

Communication

IDT clinicians should establish and maintain a relationship with the family as the pregnancy continues, supporting the family and facilitating attachment to the baby. Clinicians can help parents anticipate questions from bystanders about the pregnancy. It may be helpful to schedule prenatal visits before or after regular office hours. Some sites may offer separate childbirth education sessions separate from classes for families expecting healthy babies.38

Throughout the EPP, clinicians may find themselves reviewing test results and other prognostic information with parents on multiple occasions. Patience and compassionate listening skills are important. Clinicians should explore with parents how best to provide updates on the baby’s status before, during, and after birth. Parents may worry about how their baby will tolerate labor. Clear expectations should be established about the management plan should fetal distress occur during labor. When the plan is for non-initiation of delivery room resuscitation, good communication among the obstetric, neonatal, and pediatric teams can help make this experience the least obtrusive as possible for families, so that they can cherish the time that they have with their infant. A palliative care order set or protocol can be a helpful communication tool, and should specify orders for vital signs, medications, fluids and/or nutrition, and who should be called to declare death and complete post-mortem documentation (Box 37-1). Staff training and preparation is important, as obstetric and newborn nursery staff who typically care for healthy infants may be unfamiliar with and uncomfortable with neonatal end-of-life care.

BOX 37-1 Sample Palliative Care Order Set for Neonate Following Delivery

Creation of a Birth Plan and Advance Directive

The use of a written birth plan and advance directive can facilitate communication during the EPP.38–40 The co-creation of a birth plan between parents and clinicians provides an opportunity for parents to be actively involved in their baby’s care. As one mother eloquently stated, “this is a special kind of nesting I can do to prepare for my son.”

A well-crafted planning tool should effectively communicate the parents’ wishes for care of the mother during labor and delivery, and should be partnered with advance directives outlining appropriate medical and palliative interventions for the baby. Box 37-2 highlights possible components of a palliative care birth plan and advance directives. It is important to note that this tool is effective only if it is shared, discussed, and readily accessible to all IDT clinicians before the baby’s birth.

BOX 37-2 Components of a Prenatal Palliative Birth Plan and Neonatal Advance Directive

Summarizes parents’ overall goal for their baby

Care of Mother and Baby During Labor and Delivery • Timing, route and location of the baby’s delivery • Management of mother’s pain during labor

Some families may not want to address these issues prior to baby’s death.

Decision Making

The process of decision making in the EPP begins at diagnosis. As reflected in the case study, parents may be offered the option to terminate the pregnancy. Clinicians presenting such options should be clear about any institutional policies related to terminations, such as family counseling, ethical review, or committee approval. Decisions about termination often reflect parents’ moral, ethical and religious views. Data are limited regarding pregnancy outcome following a lethal fetal diagnosis, with two programs reporting 60 percent of parents opting to terminate the pregnancy.37,41 Termination decisions may be further complicated if the family has experienced infertility, or with the diagnosis of a life-threatening condition with one fetus of a multiple pregnancy.

For those parents who choose to continue the pregnancy, subsequent decision making is guided by the certainty of diagnosis, the certainty of prognosis, and the meaning of that prognosis to the parents.39 Together, IDT clinicians and parents work to determine those interventions that are of best interest for the baby, weighing treatment benefits and burdens. There are several congenital conditions for which neonatal resuscitation at birth is not recommended, including anencephaly and trisomy 13. In addition, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)23 and the Neonatal Resuscitation Program42 confirm that resuscitation may be forgone in any scenario if infant survival is unlikely. It is important to note that the number of conditions for which there are clear recommendations for non-resuscitation has decreased steadily over time, as medicine and technology diminish the chance that a disease will be lethal.43

Redefining Hope

Families in the EPP face the daunting task of understanding their unborn child’s poor prognosis while simultaneously waiting to meet their baby face-to-face. IDT clinicians must always be mindful that some parents may maintain seemingly unrealistic hope that the diagnosis will be proved false upon the baby’s birth. Facilitating choices in care for both mother and child can nurture a sense of control, provide meaning, and foster hope for the family in the midst of chaos and heartbreak.44 Parental hopes may shift throughout the EPP care trajectory, and IDT clinicians should be prepared to address these preferences accordingly.

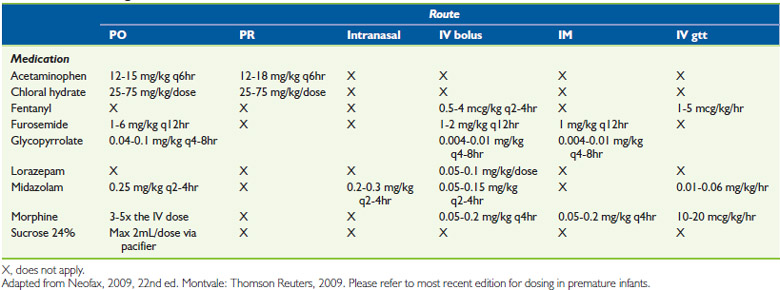

Management of Infant Suffering

IDT clinicians should anticipate and prepare for potential symptoms of infant suffering after birth. Table 37-1 presents pharmacological and non-pharmacological options for pain and symptom management. Table 37-2 presents medication dosing appropriate for term newborns and infants.

| Site of Care | Pharmacologic | Nonpharmacologic |

|---|---|---|

| In the delivery room |

Case Study Revisited

Care for the Chang family could have been improved by the following palliative care measures:

Late prenatal palliative care

Setting

A pregnant woman’s medical complications may be diagnosed during a routine prenatal visit, or she may present to a local hospital. Mothers are not always aware of the signs of preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes,4 and may delay seeking care. Mothers who present with urgent medical conditions to local hospitals that lack expertise in high-risk pregnancies may receive inaccurate prognostic information or outdated medical management. If the mother can be stabilized, she may be quickly transferred to a regional medical center far from home. If she cannot be transferred, she may deliver at the local hospital.

Interdisciplinary Team Clinicians

The IDT varies depending on the presence of a palliative care team and the institutional practice of including neonatal clinicians in prenatal decision-making. Figure 37-2 highlights typical IDT clinicians in the LPP, which can include obstetricians, nurse midwives, labor room and/or triage nurses, antepartum nurses, neonatal physicians, nurse practitioners, social workers, and chaplains. If the mother was transported, a transport nurse may be the person to spend the most amount of time with the mother and may best get to know her and her family. IDTs that do not include neonatal clinicians in the LPP can lead to distress and frustration among obstetric and neonatal nurses.

Communication

Communication during the LPP is often rushed and easily fragmented. Multiple providers speak with the family about the mother’s and infant’s conditions. A maternal-fetal medicine specialist may be the first to meet a woman after she has been transferred to a regional medical center with imminent delivery. If involved, neonatologists or neonatal nurse practitioners typically provide prognostic information to the parents regarding infant survival and morbidity. Regardless of the discipline involved, the clinicians must be knowledgeable about local and national data for infant outcome. This is especially critical because treatment decisions made by physicians have been shown to be influenced by their knowledge of outcome and the type of information that is available.45

Data suggest that women may experience a profound sense of responsibility for preventing preterm birth.46 Providers should choose their words carefully to avoid enhancing mothers’ guilt. For example, phrases such as “hold on for two more weeks” should be avoided. Mothers may also fault themselves for somehow causing premature birth. Providing accurate information is critical to reassure mothers who did nothing to cause the events.

The benefits of a prenatal tour to the NICU during a high-risk pregnancy have been documented.47 However, the practice of giving a prenatal tour is not consistent and may be dependent on the institution’s philosophy of care regarding involvement of neonatal clinicians. For mothers restricted to bed rest, information about the NICU can be presented in a variety of innovative ways, including photo albums and/or digital recordings.

Decision Making

For diagnoses made in the LPP, termination is generally not an option. Instead, decisions include:

In reality, decisions for life-threatening fetal conditions diagnosed in the LPP are often rushed and chaotic, with inadequate time to explore parents’ authentic values and goals. This may partially explain why only 36% of neonatologists say that they would defer to parent wishes for infants born in the grey zone of 23 to 24 weeks’ gestation, where prognostic uncertainty is high.48

Despite an attempt to account for prognostic indicators beyond gestational age,49 the ability to give an accurate prognosis in the LPP is limited.22 Therefore, the AAP recommends that providers guide families through a process of deciding whether to initiate life-sustaining therapies in the delivery room.23,24 A clinician skilled in newborn care should be present at delivery to evaluate the infant. Ideally, this clinician will have been a part of the management plan. The World Health Organization’s definition of “live born” should be used to document infant condition at birth.50 Parents will notice any signs of life in the infant at birth, and may need help to understand that a weak cry or reflexive movement do not change the infant’s prognosis. If the infant’s condition is the same as what was anticipated, then the plan of care can be followed. If the infant’s condition is different than anticipated or the parent requests, then treatment decisions may change from the earlier plan.

Because decision making in the LPP is often rushed and many families are unprepared for the possibility that their infant could die, recent recommendations have called for the introduction of “antenatal advanced directives.”51,52 With these recommendations, all expectant parents would receive information about extreme prematurity and be advised to consider the management options. While such directives might assist parents to be informed, it is unknown how the directives would impact the actual decisions at the time of birth.

Redefining Hope

There may not be an opportunity for hope to be redefined by parents in the LPP because of the short time between diagnosis and birth. Clinicians may feel reluctant to even begin a preliminary discussion about hope with parents because of the high probability of infant death.27,53 Clinicians can mistakenly equate hope with intact survival of an infant. In an attempt to avoid giving false hope, clinicians overemphasize poor prognostic data to try to convince parents of the gravity of the condition. Discussions about hope are most easily started by asking families what they value, and reframing hope within those parameters, such as hoping that the baby can live until a grandmother arrives.

Management of Infant Suffering

In the delivery room, drying and warming the infant are key methods for minimizing infant suffering. Additional measures to reduce infant suffering are in Tables 37-1 and 37-2.

Early neonatal palliative care

Setting

For some newborns with life-threatening conditions in the ENP, hospital discharge may be possible. Inpatient hospice is rarely available for newborns, particularly in rural areas. Home hospice is available to some, though not all, families. In one study of 62 infants who died at home, only 20 received home hospice.54 Although little research has examined parent preferences for place of death for newborns, clinical experience suggests that important family-infant bonding can occur when newborns are allowed to go home. Families often treasure the memories of a newborn sleeping in her own crib, wearing her own clothes, and being held by family members. Bonding between extended family members and the newborn has been found to improve the support of parents by the extended family during the bereavement period.55

Interdisciplinary Team Clinicians

IDT clinicians in the ENP include many prenatal and neonatal providers involved in the LPP, as well as pediatric subspecialists, child life providers, and community neonatal providers including pediatricians and the home-hospice team. Fig. 37-2 highlights some of the common roles for these providers. As with other intensive care environments, many NICUs do not integrate palliative care early in medical management. In one study, the median time between NICU palliative care consult and infant death was 2.5 days.56 A palliative care IDT member who is fully integrated into the NICU team can increase opportunities for initiating palliative care earlier into neonatal care.

Decision Making

There are several decisions particular to the ENP, which should be noted.

Because the neonatal diagnosis was not made prenatally, aggressive delivery room resuscitation is typical in these scenarios. In the first hours and days of life, as the prognosis becomes grim, decisions arise regarding whether additional therapies such as extracorporeal membranous oxygenation, should be withheld, or if current life-sustaining therapies, such as mechanical ventilation, should be withdrawn. The withholding of fluid and nutrition is particularly controversial in neonates. Some providers have concerns about withholding nutrition in light of the Baby Doe regulations.57 The 2009 report of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics reaffirms that nutrition may be withheld from newborns and infants when their benefit to the infant is outweighed by the burden.58

Management of Infant Suffering

Nearly all sick newborns in the ENP are exposed to painful intravenous access, phlebotomy, intubation and ventilation. Newborns are often agitated by concomitant exposure to cold, noise, and light. Assessing and managing neonatal pain is a skill that differs from pain assessment of older children.59 While the motor response to pain evolves and becomes more pronounced near term, perception of pain is present as early as 16 to 18 weeks’ gestation. Several scales have been developed to assess pain in infants.60–64 Only a subset of these scales are appropriate for use with premature infants.60–62 Facial grimacing is central to most of these scales; brow furrowing, nasolabial bulge, and squeezing the eyes shut also indicate pain. When facial movements are decreased by sedation, then heart rate variability can be a reliable indicator of pain.

There may be reluctance to treat sick newborns with medications that depress the central nervous system, because the neurologic exam is often a critical component of accurate diagnosis and prognosis. There may also be concern that the infant’s tenuous cardiorespiratory status will be irrevocably depressed before a clear diagnosis is made. Nevertheless, providers should strive to minimize pain and discomfort with pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies as appropriate. Refer to Tables 37-1 and 37-2.

Case Study Revisited

Several interventions might have improved care for Ms. Jones and her son.

Late neonatal palliative care

Interdisciplinary Team Clinicians

Many of the IDT clinicians in the ENP maintain important roles in the LNP. Figure 37-2 highlights some of these roles.

Communication

Poor communication among IDT clinicians, resulting in a loss of focus on the goals of care, can occur. Multiple strategies are needed to improve communication. Regular IDT meetings, with minutes distributed to missing clinicians, are helpful. This is particularly true when multiple subspecialists have recommendations that must be placed in the context of the infant’s overall condition. Family satisfaction is improved when IDT clinicians deliver consistent information.19 In settings with regularly rotating clinicians, a non-rotating IDT member, such as a social worker, may best serve as the primary contact person for the family.

Decision Making

There are several decisions particular to the LNP that should be noted.

When infants have been critically ill for weeks to months, families have often been asked to make repeated decisions about life-sustaining therapies. Some families become immune to the gravity of these discussions. They find it difficult to trust providers’ judgment of a new crisis as life-threatening when the infant has already survived similar crises in the past. Families may develop conflicting goals at different points during the hospitalization. One parent may wish to pursue all therapies regardless of the outcome, while the other wishes to focus on comfort care. Providers encourage families to talk about their disagreements. Providers should anticipate that parents’ goals often evolve over time, and decisions to not withdraw therapies early in the infant’s hospitalization may change as parents develop a greater understanding of the prognosis. It is particularly important to elicit the parents’ values regarding quality of life, as these may differ from providers’.21

Management of Infant Suffering

Infants who have had repeated painful experiences may manifest hyperalgesia in response to minor procedures such as heel sticks or immunizations.65 These older infants may tolerate a wider variety of pharmacologic formulations of analgesia and anxiolytics than newborns, such as patches, sublingual and rectal applications. Older infants may also benefit from help with secretions, gastroesophageal reflux, and anemia. Pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic strategies that reduce infant suffering are in Tables 37-1 and 37-2.

Case Study Revisited

A number of strategies could have improved care for Anna and her family.

End of Life and Bereavement Care

Memory making

For families whose infant dies around the time of birth, an entire lifetime of meeting, treasuring, and loving their babies may be wrapped up in mere minutes, hours, or days. Parents value the choice to interact and make memories with their baby during this brief time.6,8,66 Ritual to acknowledge the baby’s living and dying can provide meaning and nurture relationships among the parents, siblings and the baby.67,68 All IDT clinicians can play an integral role in facilitating such moments between parent and child.

Some families willingly accept opportunities to interact with their baby and make memories. Others may hesitate initially, but may appreciate time to consider the options. Opportunities for memory making and ritual are highlighted in Table 37-3. Families should be encouraged to interact with their baby at a pace and in ways that are most meaningful to them, even if their choices differ from how clinicians believe memories should be made (Fig. 37-4).69,70

| Photographs and Video |

|---|

| Both serve as touchstones to the family’s moments of interacting with their baby. |

| Photography Considerations |

| Photography Resources |

|---|

|

• Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep: A national organization that links volunteer photographers to families experiencing the death of a baby. www.nilmdts.org

|

| Plaster Molds |

|---|

| Molds can be created of a baby’s hands and feet using a variety of products |

| Ink Prints and Other Memories |

|---|

| Prints can be created of baby’s hands and feet on the following: |

| Locks of Hair |

|---|

| Scrapbooking |

|---|

| Personal Items |

|---|

| Memory Boxes |

|---|

| Opportunities to Interact with the Baby |

|---|

Care of the family during the dying process

Special cultural or religious actions, including proper care of the body, should be determined before the baby’s death, and implemented accordingly. A safe, private location should be established, providing families the opportunity to be with their baby’s body after death if desired. A time limit should not be imposed, as parental contact with their deceased baby’s body poses little risk for infection and also does not impact potential postmortem testing.71,72 In addition, IDT clinicians should ensure processes are in place should a mother hospitalized on a postpartum unit wish to be with her baby’s body again before discharge.73

Bereavement support

Grief support begins with the diagnosis of the life-limiting condition, and continues months after the baby’s death.2 Follow up with these families is essential. Parents’ recollections of events surrounding birth and death differ from reality, specifically concerning the infant’s condition at birth and the type of treatment that was given. The IDT can review the information with the family, even when there are no autopsy findings to review. The meeting should include IDT clinicians who can review the events around the death, provide recommendations for a subsequent pregnancy, and assess how the parents are working through their grief.

1 MacDorman M.F., Kimeyer S. Fetal and perinatal mortality, United States, 2005: National Vital Statistics Reports. vol 57:2009. National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, Md.

2 Milstein J. A paradigm of integrative care: healing with curing throughout life, “being with” and “doing to,”. J Perinatol. 2005;25:563-568.

3 Richter M.S., Parkes C., Chaw-Kant J. Listening to the voices of hospitalized high-risk antepartum patients. JOGN Nurs. 2007;36:313-318.

4 Kavanaugh K. Parents’ experience surrounding the death of a newborn whose birth is at the margin of viability. JOGN Nurs. 1997;26:43-51.

5 Limbo R., Kobler K. Will our baby be alive again? Supporting parents of young children when a baby dies. Nurs Women’s Health. 2009;13:302-311.

6 Widger K., Picot C. Parents’ perceptions of the quality of pediatric and perinatal end-of-life care. Pediatr Nurs. 2008;34:53-58.

7 Williams C., Munson D., Zupancic J., et al. Supporting bereaved parents: Practical steps in providing compassionate perinatal and neonatal end-of-life care. A North American perspective. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;13:335-340.

8 Gold K.J. Navigating care after a baby dies: A systematic review of parent experiences with health providers. J Perinatol. 2007;27:230-237.

9 Moro T., Kavanaugh K., Okuno-Jones S., et al. Neonatal end-of-life care: a review of the research literature. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2006;20:262-273.

10 Carnevale F.A., Canoui P., Cremer R., et al. Parental involvement in treatment decisions regarding their critically ill child: a comparative study of France and Quebec. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:337-342.

11 Doron M.W., Veness-Meehan K.A., Margolis L.H., et al. Delivery room resuscitation decisions for extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102:574-582.

12 Peerzada J.M., Richardson D.K., Burns J.P. Delivery room decision-making at the threshold of viability. J Pediatr. 2004;145:492-498.

13 van der Heide A., van der Maas P.J., van der Wal G., et al. The role of parents in end-of-life decisions in neonatology: physicians’ views and practices. Pediatrics. 1998;101:413-418.

14 Zupancic J.A., Kirpalani H., Barrett J., et al. Characterising doctor-parent communication in counseling for impending preterm delivery. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;87:F113-F117.

15 Bastek T.K., Richardson D.K., Zupancic J.A., et al. Prenatal consultation practices at the border of viability: a regional survey. Pediatrics. 2005;116:407-413.

16 Martinez A.M., Partridge J.C., Yu V., et al. Physician counseling practices and decision-making for extremely preterm infants in the Pacific Rim. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:209-214.

17 Partridge J.C., Martinez A.M., Nishida H., et al. International comparison of care for very low birth weight infants: parents’ perceptions of counseling and decision-making. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e263-e271.

18 Boss R.D., Hutton N., Sulpar L.J., et al. Values parents apply to decision-making regarding delivery room resuscitation for high-risk newborns. Pediatrics. 2008;122:583-589.

19 Miquel-Verges F., Woods L., Aucott S.A., Boss R.D., Donohue P.K. Prenatal consultation with a neonatologist for congenital anomalies: parental perceptions. Pediatrics. 2009;124:573-576.

20 Freda M.C., Devine K.S., Semelsberger C. The lived experience of miscarriage after infertility. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2003;28:16-23.

21 Streiner D.L., Saigal S., Burrows E., et al. Attitudes of parents and health care professionals toward active treatment of extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2001;108:152-157.

22 Chiswick M. Infants of borderline viability: ethical and clinical considerations. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;13:8-15.

23 American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Bell E.F. Noninitiation or withdrawal of intensive care for high-risk newborns. Pediatrics. 2007;119:401-403.

24 Batton D.G., Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Clinical report: ante-natal counseling regarding resuscitation at an extremely low gestational age. Pediatrics. 2009;124:422-427.

25 Hurst I. The legal landscape at the threshold of viability for extremely premature infants: a nursing perspective, part II. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19:253-262. quiz 263–264

26 Hurst I. The legal landscape at the threshold of viability for extremely premature infants: A nursing perspective, part I. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19:155-166. quiz 167–168

27 Kavanaugh K., Savage T., Kilpatrick S., et al. Life support decisions for extremely premature infants: Report of a pilot study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20:347-359.

28 Evans W.G., Tulsky J.A., Back A.L., et al. Communication at times of transitions: how to help patients cope with loss and redefine hope. Cancer J. 2006;12:417-424.

29 Pector E.A. Views of bereaved multiple-birth parents on life support decisions, the dying process, and discussions surrounding death. J Perinatol. 2004;24:4-10.

30 Kenner C., Boykova M. Palliative care in the neonatal intensive care unit. In: Ferrell B., Coyle N., editors. Textbook of palliative nursing. ed 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010:1065-1080.

31 Kain V.J. Moral distress and providing care to dying babies in neonatal nursing. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2007;13:243-248.

32 Papadatou D. In the face of death: professionals who care for the dying and the bereaved. New York: Springer, 2009.

33 Papadatou D. A proposed model of health professionals’ grieving process. Omega. 2000;41:59-77.

34 Roehrs C., Masterson A., Alles R., et al. Caring for families coping with perinatal loss. JOGN Nurs. 2008;37:631-639.

35 Epstein E.G. End-of-life experiences of nurses and physicians in the newborn intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2008;28:771-778.

36 Rogers S., Babgi A., Gomez C. Educational interventions in end-of-life care: Part I: An educational intervention responding to the moral distress of NICU nurses provided by an ethics consultation team. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8:56-65.

37 Leuthner S., Jones E.L. Fetal Concerns Program: A model for perinatal palliative care. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32:272-278.

38 Sumner L.H., Kavanaugh K., Moro T. Extending palliative care into pregnancy and the immediate newborn period: state of the practice of perinatal palliative care. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2006;20:113-116.

39 Leuthner S.R. Palliative care of the infant with lethal anomalies. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:747-759. xi

40 Munson D., Leuthner S.R. Palliative care for the family carrying a fetus with a life-limiting diagnosis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:787-798. xii

41 Breeze A.C., Lees C.C., Kumar A., et al. Palliative care for prenatally diagnosed lethal fetal abnormality. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F56-F58.

42 Kattwinkel J., editor. The textbook of neonatal resuscitation. Elk Grove Village, I11: Academy of Pediatrics and the American Heart Association, 2006.

43 Koogler T.K., Wilfond B.S., Ross L.F. Lethal language, lethal decisions. Hastings Cent Rep. 2003;33:37-41.

44 Milstein J.M. Introducing spirituality in medical care: transition from hopelessness to wholeness. JAMA. 2008;299:2440-2441.

45 Janvier A., Lantos J., Deschênes M., et al. Caregivers attitudes for very premature infants: What if they knew? Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:276-279.

46 MacKinnon K. Living with the threat of preterm labor: women’s work of keeping the baby in. JOGN Nurs. 2006;35:700-708.

47 Griffin T., Kavanaugh K., Soto C.F., et al. Parental evaluation of a tour of the neonatal intensive care unit during a high-risk pregnancy. JOGN Nurs. 1997;26:59-65.

48 Singh J., Fanaroff J., Andrews B., et al. Resuscitation in the “gray zone” of viability: Determining physician preferences and predicting infant outcomes. Pediatrics. 2007;120:519-526.

49 Tyson J.E., Parikh N.A., Langer J., et al. Intensive care for extreme prematurity: moving beyond gestational age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1672-1681.

50 World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. vol 2:1993: 129. Geneva, Switzerland

51 Harrison H. The offer they can’t refuse: parents and perinatal treatment decisions. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;13:329-334.

52 Catlin A. Thinking outside the box: Prenatal care and the call for a prenatal advance directive. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19:169-176.

53 Reder E.A., Serwint J.R. Until the last breath: exploring the concept of hope for parents and health care professionals during a child’s serious illness. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:653-657.

54 Leuthner S.R., Boldt A.M., Kirby R.S. Where infants die: examination of place of death and hospice/home health care options in the state of Wisconsin. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:269-277.

55 Lauer M.E., Mulhern R.K., Schell M.J., et al. Long-term follow-up of parental adjustment following a child’s death at home or hospital. Cancer. 1989;63:988-994.

56 Pierucci R.L., kirby R.S., Leuthner S.R. End-of-life care for neonates and infants: the experience and effects of a palliative care consultation service. Pediatrics. 2001;108:653-660.

57 Child Abuse and Prevention Act. 42 U.S.C. § 5101. 1994.

58 Diekema D.S., Botkin J.R., Committee on Bioethics American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical report: forgoing medically provided nutrition and hydration in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:813-822.

59 Batton D.G., Barrington K.J., Wallman C. Prevention and management of pain in the neonate: an update. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2231-2241.

60 Stevens B., Johnston C., Petryshen P., et al. Premature Infant Pain Profile: development and initial validation. Clin J Pain. 1996;12:13-22.

61 Grunau R.V., Johnston C.C., Craig K.D. Neonatal facial and cry responses to invasive and non-invasive procedures. Pain. 1990;42:295-305.

62 Krechel S.W., Bildner J. CRIES: A new neonatal postoperative pain measurement score: initial testing of validity and reliability. Paediatr Anaesth. 1995;5:53-61.

63 van Dijk M., de Boer J.B., Koot H.M., et al. The reliability and validity of the COMFORT scale as a postoperative pain instrument in 0 to 3-year-old infants. Pain. 2000;84:367-377.

64 Lawrence J., Alcock D., McGrath P., et al. The development of a tool to assess neonatal pain. Neonatal Netw. 1993;12:59-66.

65 Taddio A., Shah V., Gilbert-MacLeod C., et al. Conditioning and hyperalgesia in newborns exposed to repeated heel lances. JAMA. 2002;288:857-861.

66 Meert K.L., Thurston C.S., Briller S.H. The spiritual needs of parents at the time of their child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit and during bereavement: a qualitative study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:420-427.

67 Kobler K., Limbo R., Kavanaugh K. Meaningful moments: The use of ritual in perinatal and pediatric death. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32:288-295. quiz 296–297

68 Fanos J.H., Little G.A., Edwards W.H. Candles in the snow: ritual and memory for siblings of infants who died in the intensive care nursery. J Pediatr. 2009;154:849-853.

69 Daley M., Limbo R., editors. Creating memories. RTS bereavement training in early pregnancy loss, stillbirth, and newborn death. La Crosse, Wis: Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation, 2008.

70 Schwarz B., Fatzinger C., Meier P.P. Rush SpecialKare Keepsakes. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2004;29:354-361. quiz 362–363

71 Pregnancy Loss and Infant Death Alliance. PLIDA position statement: Infection risks are insignificant. www.plida.org/pdf/infectionRisks.pdf.. Accessed July 26, 2009

72 Pregnancy Loss and Infant Death Alliance. PLIDA position statement: Delaying postmortem pathology studies. www.plida.org/pdf/PostmemPath.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2009

73 Pregnancy Loss and Infant Death Alliance. PLIDA position statement: Bereaved parents holding their baby. www.plida.org/pdf/PLIDA_Statement_Holding_Baby_FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2009

weeks’ gestation with bulging membranes and preterm labor. She had been monitored closely during prenatal care because of bleeding in the first trimester. A cerclage was placed early on in her pregnancy because of a history of preterm labor 3 years because prior. For that pregnancy, she selected a rescue cerclage at 20 weeks’ gestation over termination, and gave birth to a premature infant at 36 weeks’ gestation who suffered no major complications.

weeks’ gestation with bulging membranes and preterm labor. She had been monitored closely during prenatal care because of bleeding in the first trimester. A cerclage was placed early on in her pregnancy because of a history of preterm labor 3 years because prior. For that pregnancy, she selected a rescue cerclage at 20 weeks’ gestation over termination, and gave birth to a premature infant at 36 weeks’ gestation who suffered no major complications.