Chapter 32 PREMENSTRUAL SYNDROME AND PREMENSTRUAL DYSPHORIC DISORDER

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is characterized by the cyclic recurrence of symptoms during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a severe form of PMS. Of women of reproductive age, 80% have physical changes, such as breast tenderness or abdominal bloating, that are associated with menstruation; of these women, 20% to 40% experience symptoms of PMS, and 2% to 10% report severe disruption of their daily activities. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommends the PMS diagnostic criteria developed by the University of California at San Diego and the National Institute of Mental Health. These criteria are presented in Box 32-1.

Box 32-1. Diagnostic Criteria for Premenstrual Syndrome

From American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Practice Bulletin: Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 15, April 2000. Premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:1-9; and Kessel B: Premenstrual syndrome. Advances in diagnosis and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2000;27:625-39.

Features of PMDD and depressive disorders overlap considerably. A family history of depression is common in women diagnosed with moderate to severe PMS. Despite the overlap between PMDD and depressive disorders, many patients with PMDD do not have depressive symptoms; therefore, PMDD should not be considered simply a variant of depressive disorder. The diagnostic criteria for PMDD from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, are presented in Box 32-2.

Box 32-2. Research Criteria for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

A. In most menstrual cycles during the past year, five (or more) of the following symptoms were present for most of the time during the last week of the luteal phase, began to remit within a few days after the onset of the follicular phase, and were absent in the week after menses, with as least one of the symptoms being 1, 2, 3, or 4:

B. The disturbance markedly interferes with work or school or with usual social activities and relationships with others (e.g., avoidance of social activities, decreased productivity and efficiency at work or school).

C. The disturbance is not merely an exacerbation of the symptoms of another disorder, such as major depressive disorder, panic disorder, dysthymic disorder, or a personality disorder (although it may be superimposed on any of these disorders).

D. Criteria A, B, and C must be confirmed by prospective daily ratings during at least two consecutive symptomatic cycles. (The diagnosis may be made provisionally before this confirmation.)

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994:717-718.

Key Historical Features

Suggested Work-Up

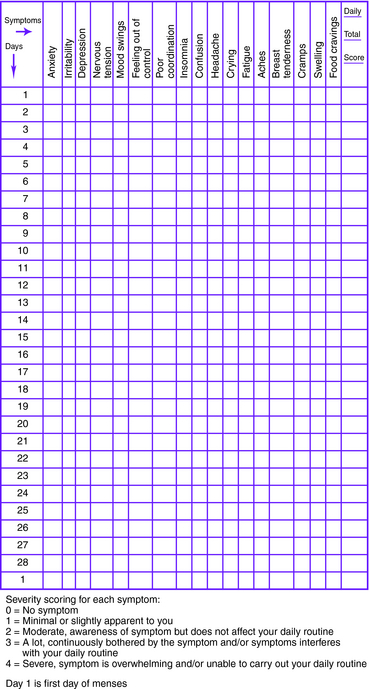

The timing of symptoms should be confirmed with a prospective symptom and menstrual period record kept by the patient for at least two or three menstrual cycles. In the Daily Symptom Report, a self-reporting scale presented in Figure 32-1, patients rate each symptom on a 5-point scale from 0 (none) to 4 (severe). The scale provides guidance for scoring the severity of each symptom and may be used in the office setting for the diagnosis and assessment of PMDD.

Figure 32-1. Daily symptom report.

(From Freeman EW, DeRubeis RJ, Rickels K: Reliability and validity of a daily diary for premenstrual syndrome. Psychiatry Res 1996;65:97-106.)

Diagnostic criteria for PMS and PMDD are outlined in Boxes 32-1 and 32-2.

Additional Work-Up

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | If a thyroid disorder is suspected |

| Complete blood cell count (CBC) | If anemia is suspected |

| Measurement of fasting blood glucose | If diabetes is suspected |

| Measurement of electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and albumin | If an eating disorder is suspected |

| Toxicology screen | If substance abuse is suspected |

| Abdominal ultrasonography, laparoscopy, or both | If endometriosis is suspected |

ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 15, April 2000. Premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:1-9.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:717-718.

Bhatia SC, Bhatia SK. Diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1239-1248.

Dickerson LM, Mazyck PJ, Hunter MH. Premenstrual syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:1743-1752.

Freeman EW, DeRubeis RJ, Rickels K. Reliability and validity of a daily diary for premenstrual syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1996;65:97-106.

Frye GM, Silverman SD. Is it premenstrual syndrome? Keys to focused diagnosis, therapies for multiple symptoms. Postgrad Med. 2000;107(5):151-154. 157-159

Grady-Weliky TA. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:433-438.

Johnson SR. Premenstrual syndrome, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and beyond: a clinical primer for practitioners. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:845-859.

Kessel B. Premenstrual syndrome. Advances in diagnosis and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:625-639.

Molin ML, Zendell SM. Evaluating and managing premenstrual syndrome. Medscape Womens Health. 2000;5:1-16.