Chapter 33 Premenstrual syndrome

With contribution from Dr Gillian Singleton

Introduction

A great majority of women will experience premenstrual symptoms at some time in their lives. Some women, however, experience more severe and troublesome symptoms that can impact daily living. This condition is defined as premenstrual syndrome (PMS). PMS can affect up to 90% of women of childbearing age with 2–10% of women experiencing severe, incapacitating symptoms. PMS is characterised by the cyclical recurrence of broad and varied symptoms which are in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, and which remit at the onset of menstruation or in the days following.1–5 These symptoms include emotional, behavioural and physical symptoms (which are outlined in more detail in Table 33.1).6,7 Some women predominantly experience mood, cyclical mastalgia or dysmenorrhoea symptoms during the luteal phase.

| Psychological | Irritability, anger, depressed mood, tearfulness, anxiety, tension, mood swings, difficulties with concentration and memory, confusion, restlessness, decreased self-esteem, tension, feelings of being overwhelmed, of loneliness and hopelessness |

| Behavioural | Insomnia, changes in libido, food cravings or overeating |

| Physical | Fatigue, dizziness, headaches, mastalgia, back pain, abdominal pain and bloating, weight gain, constipation, fluid retention (up to 1kg of weight), nausea, myalgias and arthralgias |

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD)

When premenstrual symptoms are dominated by severe disturbances of mood and behaviour that are associated with major disruption to daily activities and relationships, the condition is known as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).3 PMDD affects around 3–5% of women of reproductive age.5, 8, 9

Some studies have found an association between the luteal phase and exacerbations of psychiatric disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, increased alcohol consumption in alcoholism, and increased incidence of suicide attempts. This postulates serotonin dysregulation as a possible causative factor.10

The DSM IV diagnostic criteria for PMDD include at least 5 of 11 symptoms occurring in the week prior to menstruation for the majority of months of the previous year, which remit in the post-menstrual week.11 These symptoms markedly interfere with daily activities and interpersonal relationships.

Table 33.2 lists the common symptoms of PMDD.

| Depressive symptoms |

Affective lability. Suddenly feeling sad or tearful, with increased sensitivity to personal rejection

|

Dysmenorrhoea

Primary dysmenorrhoea is defined as the occurrence of painful menstrual cramps, in the absence of pelvic pathology, and occurs in up to 80% of young women, with over 50% of these individuals experiencing limitations to their daily activities, such as work and schooling.12 Primary dysmenorrhoea is hypothesised to be caused by uterine contractions in response to prostaglandin, leukotriene and vasopressin release.

Cyclical mastalgia

Breast pain or mastalgia is a common symptom experienced by women especially in the premenstrual phase. Overall, 92% of patients with cyclical mastalgia and 64% with non-cyclical mastalgia can obtain relief of their pain with the use of available therapies.13

Aetiology of premenstrual symptoms

Role of complementary medicine and integrative therapies in PMS

The use of complementary medicine is popular amongst women with PMS, PMDD and dysmenorrhoea and plays an important role in management of symptoms.14 While mainstream medical treatment for PMS is commonly used, a large scale survey of medical and nurse practitioners, including gynaecologists, indicated that at least 90% reported recommending at least 1 complementary therapy, primarily for pain management for women with PMS.15 Chiropractic, acupuncture, massage, and behavioural medicine techniques such as meditation and relaxation training were cited as the most commonly recommended.

A 2003 systematic review16 identified 33 randomised control trials (RCTs) for complementary medicine use in PMS, 13 of which were for dysmenorrhoea. There is an increasing body of evidence supporting the use of complementary therapies and lifestyle interventions in the management of PMS symptoms. To date a number of therapeutic interventions including calcium supplementation, vitex agnus castus, stress reduction, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and relaxation therapy and exercise have been shown to be beneficial. The authors’ conclude that preliminary studies indicate a role for further research on magnesium, vitamin B1 and B6, low-fat diet, fish oil supplementation for dysmenorrhoea, St John’s wort and L-tryptophan supplementation for PMDD.16

Another review of the literature for treatment of PMS and PMDD identified a number of useful non-pharmacological treatments with some evidence for efficacy including cognitive behavioural relaxation therapy, aerobic exercise, as well as calcium, magnesium, vitamin B6, L-tryptophan supplementation and a complex carbohydrate drink. 17

General lifestyle interventions

Symptom diary and management

The PMS Symptom Management Program (PMS-SMP) includes non-pharmacological strategies incorporating self-monitoring, emphasis on personal choice, self-regulation, and self/environmental modification, with peer support and professional guidance. A study designed to establish the effectiveness of this program randomised 91 women with severe PMS to early treatment groups (n = 40) or waiting treatment groups (n = 51) over an 18-month period.18 The PMS-SMP was effective in reducing PMS severity by 75%, premenstrual depression, and general distress by 30–54%, as well as increasing wellbeing and self-esteem in women experiencing severe PMS compared with antidepressant drug treatments that report a 40–52% reduction in PMS severity in studies. The improvement was maintained in the long-term follow-up.18

Mind–body medicine

Cognitive and behavioural interventions

Improving knowledge, supportive therapy, addressing dysfunctional thinking and encouragement of behavioural changes can significantly impact on women’s perception of PMS and menstruation and on their ability to better manage their symptoms appropriately. Educating women about the biological changes in their bodies has been reported to facilitate an increased sense of control and relief of symptoms.19

There has been evidence of an increased placebo-response rate demonstrated in symptomatic improvement from formal psychological interventions such as relaxation therapy and CBT in some studies.20 These interventions include keeping a symptom diary to help identify when behavioural and psychological changes are necessary, having adequate rest and exercise, and making healthy dietary changes.21

A number of studies have supported the role of CBT in managing PMS, particularly for pain and dysphoric symptoms. A study of 84 women with PMS, examined the efficacy of enhanced coping skills training that included cognitive restructuring, reducing negative emotions, effective problem-solving assertiveness and relaxation training, in direct comparison with hormone treatment with Duphaston, a synthetic progestogen.22 The group of women randomised to coping skills training obtained substantial relief of affective and cognitive symptoms when compared to women in the hormone therapy group; this relief was particularly noted in women with severe PMS symptoms. These symptomatic benefits persisted at the 3-month follow-up following intervention.22

A 2005 Cochrane systematic review of 14 RCTs looking at management strategies for chronic pelvic pain, demonstrated that ‘counselling supported by ultrasound scanning was associated with reduced pain and improvement in mood’.23

A 2007 Cochrane systematic review of the effectiveness of behavioural therapies in management of dysmenorrhoea included 5 RCTs. The results of this review demonstrated that there is some evidence for the use of behavioural interventions such as relaxation techniques and pain management training in reducing symptoms to cause fewer restrictions in daily activities.24

Another study aimed to modify dysfunctional thinking as a means of impacting on negative premenstrual symptoms.25 The CBT group involved cognitive restructuring and assertion training. A comparison group called ‘information-focused therapy’ (IFT) were presented with information only on relaxation training, nutritional and vitamin guidelines, dietary and lifestyle recommendations, and assertion training, and did not address belief restructuring. Both groups equally displayed amelioration of anxiety, depression, negative thoughts and physical changes in women with PMS.

A 2009 systematic review of studies that investigated the use of CBT for PMS or PMDD identified 3 RCTs comparing CBT with pharmacotherapy and a number of case studies.26 The researchers highlighted the benefits of applying mindfulness and acceptance-based CBT interventions to individuals with PMS/PMDD and suggested more methodologically rigorous research be done in this area.

Stress reduction, relaxation therapies and massage

A 2004 study of 114 women divided them into high and low symptom severity PMS groups and compared these groups on stress and QOL variables. The results revealed that women with severe PMS symptoms had significantly more stress and poorer QOL than women with low symptom scores.27

A 5-month study published in Obstetrics and Gynecology, examined the effects of the relaxation response on PMS symptoms in 46 women who were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: a charting group who kept a daily diary of symptoms experienced, a reading group who read leisure material twice daily in combination with charting symptoms, and a relaxation response group who elicited a relaxation response twice daily as well as charting symptoms.28 The relaxation response group showed significant improvement (58.0%), in comparison to the reading groups (27.2%) and the charting group (17.0%) of reduction in physical and emotional symptoms. The authors conclude that ‘regular relaxation response is an effective treatment for physical and emotional premenstrual symptoms, and is most effective in women with severe symptoms’.28

Another trial had 24 women with PMDD randomly assigned to either a massage therapy or a relaxation therapy group (Progressive Muscle relaxation therapy).29 The massage therapy group demonstrated reduction in pain, anxiety and depressed mood immediately after the massage sessions, especially in women treated weekly for 5 weeks, who also experienced reduced fluid retention and overall menstrual distress. The relaxation group also demonstrated improved symptoms but not to the same degree of benefit from massage therapy. While the findings demonstrate massage therapy may be an effective short-term treatment for severe symptoms of PMS, no long-term changes were observed in the massage therapy group.

Sleep

Sleep disturbances are common in women with severe symptoms of PMS, PMDD and dysmenorrhoea. Variations in core temperature, metabolic rate and hormones throughout the menstrual cycle may contribute to changes in sleep patterns and quality of sleep particularly in the luteal phase and menstruation.30 Women experiencing negative mood changes in the premenstrual period also demonstrate significantly less delta wave sleep during both menstrual cycle phases in comparison with asymptomatic subjects.31 Evidence also indicates that variations in other circadian rhythms, such as melatonin and cortisol, may also be affected in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle which may negatively impact sleep patterns.

A study of 68 nurses under 40 years of age completed a survey evaluating sleep, menstrual function and pregnancy outcomes. Fifty-three percent of the women noted menstrual changes when working shift work and the findings suggest that sleep disturbances may lead to menstrual irregularities, and changes in menstrual function.32 Another study also demonstrated how disruption of circadian rhythms as seen in women working night shifts are more likely to report menstrual irregularities, longer menstrual cycles, abnormalities of reproductive function and mood changes than non-shift workers.33 The authors also concluded there was accumulating evidence ‘that circadian disruption increases the risk of breast cancer in women, possibly due to altered light exposure and reduced melatonin secretion’.33

Sunshine and vitamin D

In a very small study of women suffering polycystic ovarian disease, they received 50 000IU of vitamin D weekly or biweekly, and this helped to normalise their menstrual cycles in over 50% of patients.34 Whilst the exact underlying mechanism is unclear, it would appear more research is warranted in this area as vitamin D deficiency is common, particularly in cooler climates, in dark skinned women and women with certain dress codes (e.g. veils), and vitamin D may play an important hormone regulatory effect. It is also documented that vitamin D plays an important role in mood regulation, amelioration of depression, myalgias, back pain and in the management of migraine headaches and thus may reduce some of the symptoms experienced with PMS, PMDD and dysmenorrhoea (see chapters on depression, headaches and migraines and musculoskeletal medicine for more references).35–38

Interestingly, a number of controlled studies of active bright light therapy in the late luteal phase significantly reduced depression and pre-menstrual tension scores in women with PMDD, compared to baseline, while placebo dim red light treatment did not.39, 40 These results suggest that bright light therapy can be an effective treatment for depression in the luteal phase, although exposure to daily sunshine and/or vitamin D supplementation (especially if sunshine exposure is not possible), may obviously be more feasible and convenient.

Physical activity/exercise

A prospective study examined the relationship between exercise participation and menstrual pain, physical symptoms, and negative mood in 21 sedentary women and 20 women who participated in regular exercise for 2 complete menstrual cycles.41 All women experienced pain during menses compared to the follicular and luteal phases. The findings demonstrated that exercise participants reported less pain than sedentary women during menses, however there was no reported difference in pain experienced in the follicular and luteal phases between the groups. The sedentary group also reported greater symptoms of anxiety during menses. Likewise, another study demonstrated moderate exercise training without major weight, hormonal or menstrual cycle alteration significantly reduced premenstrual and menstrual symptoms including circulatory symptom problems, psychic tension, irritable behaviour, belligerence, and other personality alterations.42

A preliminary study of middle-aged women demonstrated that women with PMS who practised regular aerobic exercise reported fewer symptoms than the control subjects.43

In a prospective, controlled 6-month trial of exercise training, 2 groups of women, 1 previously sedentary, were commenced on a 6-month conditioning exercise program of increased running or marathon training, and were compared with a control group of women who were not actively involved in an exercise training program but were normally active.44 Over the 6-month period of the study the first 2 groups demonstrated a reduction in PMS symptoms including fluid retention, depression and anxiety symptoms compared with the control group of women. The control group demonstrated no change in PMS symptomatology. This study demonstrates the direct positive effects of conditioning exercise on PMS. There was no documented hormonal, menstrual cycle, or weight changes in either groups.44

Nutritional influences

Diet

Fish

A 1995 study of a group of Danish women, which analysed dietary intake of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and correlated results with severity of menstrual pain, demonstrated that a higher ratio of dietary omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids correlates with reduced menstrual pain.45

Vegetarian plant-based diet

A study of 33 women over 4 menstrual cycles was conducted in which the women adhered solely to a plant-based vegetarian diet for 2 menstrual cycles then returned to their normal diets and took a placebo supplement for a further 2 cycles. This study demonstrated that a low-fat, plant-based vegetarian diet of grains, vegetables, legumes and fruits, significantly reduced the duration (from 3.9 to 2.7 days) of pain and reduced associated premenstrual symptoms such as fluid retention and behavioural changes when the diet cycles were compared to the placebo cycles on a normal diet.46 Several reasons were postulated for its benefit. The plant-based dietary factors were found to raise serum sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG) by 19% in the diet phase compared to the supplement phase. SHBG binds and inactivates estrogens. It is hypothesised that estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium is then reduced which in turn may limit proliferation of tissues which produce prostaglandins. Another possible reason for symptomatic benefit is that vegetarian diets are generally lower in total fat and that the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids is increased compared to diets rich in animal fats, which results in reduced fluid retention and reduced dysmenorrhoea.

Calcium and vitamin D dietary intake

A case-controlled study within the prospective Nurses Health Study II cohort of women aged 27–44 years free from PMS at baseline were followed up over a 10-year period and assessed for dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D by using a food frequency questionnaire to correlate with development of PMS.47

After adjustment for age, parity, smoking status, and other risk factors, women with the highest vitamin D intake (median, 706IU/day) experienced a 40% reduction in the development of PMS symptoms when compared with those in the lowest intake group (median, 112IU/day). Similarly, women with the highest intake of dietary calcium food sources, such as skim or low-fat milk, were also inversely related to PMS, with a 30% risk reduction of developing PMS compared with women with a low intake (median, 529mg/day).47 Further large-scale clinical trials are warranted to confirm these findings.

Caffeine restriction

A 1985 study investigated the possible association between severity of premenstrual symptoms and consumption of caffeine. The study concluded that consumption of caffeine-containing beverages was strongly associated with PMS symptoms. A dose-dependant relationship was found in women with severe premenstrual symptoms.48

Nutritional supplements

Vitamins

Vitamins B6 and B1

There is an increasing body of evidence supporting the use of vitamins B6 and B1 in PMS.

A 2001 Cochrane review, identified 1 small randomised placebo-controlled trial of vitamin B6 which showed that it was more effective at reducing pain than both placebo and a combined formula of magnesium and vitamin B6.49

A 2009 systematic review of 10 RCTs of herbs and nutrients suggests that chasteberry herb and vitamin B6 may be effective for PMS, although there was stronger evidence for the use of calcium. The review concluded that vitamin B6 supplementation in doses of 50–100mg/day are likely to be of benefit in reducing premenstrual symptoms.50

It should be noted, however, that these doses are far in excess of the recommended daily intake (RDI) of this vitamin and that there is a risk of toxicity if daily doses of 50mg are exceeded. Several cases have been reported to the Australian Adverse Drug Reaction Advisory Committee (ADRAC) in recent years reporting neuropathy which can present with paresthesia, nerve shooting pains, hyperaesthesia and muscle fasciculation in patients taking more than 50mg of vitamin B6/day and thus excessive doses for prolonged periods of time should obviously be avoided.51 Patients should be warned to stop taking vitamin B6 if they should develop unexplained neurological symptoms suggestive of peripheral neuropathy, such as tingling, burning and numbness of limbs.

One large trial identified by the 2001 Cochrane review demonstrated that 100mgs/day of vitamin B1 to be more effective than placebo in reducing dysmenorrhoea. Vitamin B1 (thiamine) is generally well tolerated, however its absorption may be impaired by concomitant intake of antibiotics, iron and tannins and thus intake of these substances should be separated by 2 hours.11, 49

Vitamin E

There is conflicting evidence on the potential role of vitamin E in the management of dysmenorrhea.

In a more recent placebo-controlled trial published in the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology in 2005, 278 teenage girls with primary dysmenorrhoea were randomised to either vitamin E supplements or placebo.52 Both groups were permitted to consume 200mgs of ibuprofen 8-hourly for pain as needed. The vitamin E group were instructed to take vitamin E 200mgs twice daily for 5 days (two days before and 3 days after the beginning of menstruation) over 4 consecutive menstrual periods. A symptomatic questionnaire was used to establish the severity and duration of the pain, and also to measure blood loss. The vitamin E group demonstrated significantly less pain, of shorter duration, requiring less consumption of ibuprofen (4.3%) compared with the placebo group (89.4%) for pain. They also noted significant reduction in menstrual blood loss, without any significant side-effects. The mechanism of action for vitamin E is not clear, but is thought to be due to the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, which is implicated as a cause of uterine contraction pain.

Minerals

Magnesium

A 2001 Cochrane review identified 3 small trials that compared the effects of magnesium and placebo for pain relief in women with dysmenorrhoea.49 Overall the trials showed magnesium to be more effective than placebo for pain relief and the women required less concomitant analgesic medication with its use. There were minimal adverse effects reported. The author’s conclude that ‘magnesium is a promising treatment for dysmenorrhoea’, but it was uncertain from the trials which dose or regime of treatment should be used.49

A 1991 small double-blinded randomised placebo-controlled trial examined the effects of supplementation of 360mg/day of magnesium on premenstrual mood changes. Results demonstrated that magnesium supplementation lessened mood symptoms in women with previous PMS compared to placebo.53

Calcium

There exists some good evidence to justify the recommendation for use of calcium in PMS. A 2009 systematic review of RCTs found good quality evidence for the use of calcium in PMS.50

According to a large case-control study published in Archives of Internal Medicine 2005,54 individuals in the highest quintile of dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D had the risk of PMS reduced by 30%, compared to those with the lowest level of intake. Individuals who ingested 4 or more servings of low-fat milk per day had a 46% reduction in risk compared with women who drank milk once a day. In light of the many health benefits of increased calcium and vitamin D intake including reduced risk of osteoporosis, researchers suggest recommending increased intake of foods rich in these nutrients, even for younger women.

A large study of 466 women reported in The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology55 showed that 1200mg calcium carbonate versus a placebo taken over 3 months produced a significant reduction in pain and discomfort, fluid retention, mood disorders, and food cravings (48% effective compared to 30% with placebo) in the premenstrual phase.

Calcium may cause constipation and flatulence and should not be co-administered with zinc, magnesium or caffeine. Calcium is best combined with magnesium and vitamin D. Calcium can also interact with calcium channel blockers and cardiac glycosides; high-dose supplementation should be avoided with these medications.56

Zinc

Zinc may play a role in the alleviation of dysmenorrhoea, however the current evidence for this is weak. An analysis of 5 case studies of women using up to 30mg of zinc once to 3 times a day for 1 to 4 days immediately prior to menses was able to prevent dysmenorrhoea although the researchers recommended additional study.57 Whilst no side-effects were recorded in the case studies, it is uncertain if high dose zinc may impact on pregnancy. So, women should be warned to avoid pregnancy if taking high doses of zinc for PMT. The author postulated that zinc, like the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs used to treat cramping, reduces the production of prostaglandins or zinc improves micro-vessel circulation to help prevent cramping and pain.58

Omega-3 fatty acids

In a 4-month double-blinded randomised placebo-controlled trial, 42 teenage girls with dysmenorrhoea were randomised to either fish oil (720mgs DHA and 1080mgs EPA) plus 1.5mg of vitamin E supplements or placebo for 2 months, then the treatment groups switched treatments for a further 2 months.58 After 2 months of the fish oil/vitamin E treatment, there was a marked reduction in symptoms and requirement for analgesia, compared with no changes demonstrated in the placebo groups. Of interest, the dietary intake of fish for most of the girls in the study was extremely low.

Tryptophan

Tryptophan is an amino acid which is naturally found in dairy products, seafood, red and white meat, nuts, seeds and soy products and is a precursor to niacin and serotonin. Serotonin depletion has been hypothesised to play a role in premenstrual dysphoria. This hypothesis has been examined in a number of small studies. One such study examined the effects of acute tryptophan depletion on 16 women with PMS. Tryptophan depletion was associated with a significant worsening of premenstrual mood symptoms which correlated with a reduction in tryptophan levels relative to other amino acids suggesting a role for this serotonin precursor.59

A number of small studies have demonstrated a positive effect of tryptophan supplementation on premenstrual dysphoria symptoms. In 1 randomised placebo-controlled trial of 71 patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder, patients were treated with either 6g/day of L-tryptophan or placebo from day 17 to day 23 of the menstrual cycle over 3 consecutive cycles. There was a statistically significant improvement in dysphoria, irritability, tension and mood swings in the tryptophan group compared to the placebo group.60

Another double-blinded cross-over small study of 12 women with PMS examined the effects of a carbohydrate-rich beverage known to increase serum tryptophan levels compared to 2 other iso-caloric beverages in the luteal phases over 3 menstrual cycles preceded by a 1-month placebo cycle. Symptoms of depression, anger, confusion and carbohydrate cravings were reduced significantly when the experimental carbohydrate beverage was consumed compared to the iso-caloric beverages which did not impact serum tryptophan levels. Interestingly, the ability of the women to perform memory word recognition tasks was improved after consumption of the experimental beverage compared to placebo.61

There is a risk of significant interactions if tryptophan is taken with antidepressants and lithium. Side-effects include dry mouth, nausea, headaches and tremors. In 1989 the FDA in the United States reported an association between the consumption of a particular Japanese manufactured L-tryptophan and fatalities from eosinophilia myalgia syndrome.62 This disorder is thought to have been related to a contaminant which arose in the process of creating L-tryptophan from genetically modified bacteria by the manufacturer.

Herbal medicine

Red clover (Isoflavones)

Isoflavones are a subgroup of phytoestrogens that have a weak anti-oestrogenic effect on oestrogen receptor sites in pre-menopausal women. A double-blind RCT of either placebo, 40mg or 80mg of isoflavones in 18 women demonstrated that 9 of the 12 women on treatment had a worthwhile improvement in their cyclical mastalgia symptoms, compared to only 2 of 6 on placebo.63 Pain reduced by 13% for placebo, 44% for 40mg of isoflavone per day and 31% for 80mg/day.

Chasteberry (vitex agnus castus)

Perhaps the best researched herb for PMS to date, is vitex agnus castus (VAC). Its use dates back to Hippocrates. A trial was published in Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics of 50 women with PMS who were treated with 20mgs/day of Ze440 (VAC extract) over 3 menstrual cycles.64 The patients were studied over 8 menstrual cycles, 2 baseline, 3 treatment and 3 post-treatment. Symptoms reduced by 42.5% in the group during the treatment phase and interestingly symptoms remained 21.7% below baseline symptoms in the 3 cycles post-treatment cessation. The main criticism of this study is that it was not blinded or placebo controlled.

A randomised, placebo-controlled trial of 170 women, published in the British Medical Journal (2001), concluded that a specific extract of VAC Ze440 (180mgs) was ‘an effective and well-tolerated treatment for the relief of symptoms’ of PMS.65 Women selected for the trial were diagnosed with the PMS on the basis of DSM II R criteria and took either the placebo or VAC treatment for 3 months. Compared with placebo, the VAC group demonstrated statistically significant improvement (52% response rate compared to the placebo response of 24%) of PMS symptoms including irritability, mood alteration, anger, headache and breast fullness. Abdominal bloating was the only measured symptom which did not have a significant response to VAC.

A 2007 review which examined the results of 2 non-randomised and 3 randomised controlled studies (two with placebo and 1 with fluoxetine) for a total of 1991 women concluded that VAC was ‘safe, effective and efficient in the treatment of cyclical mastalgia’.66

A 2003 randomised trial of 41 women compared fluoxetine (a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor [SSRI]) with a VAC extract (20–40mg/day) for the treatment of PMDD.67 Patients’ symptoms improved equally for Fluoxetine (68.4%) — this group demonstrated a significant reduction, particularly in psychological symptoms — and VAC (57.9%) which demonstrated a significant effect in relieving mainly physical symptoms. Unfortunately, there was no placebo arm in this study, so these findings need to be interpreted with caution.

St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Animal studies have demonstrated that Hypericum inhibits the reuptake of serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine and upregulates serotonin receptors and thus may play a role in ameliorating premenstrual dysphoria symptoms.68

A 2008 Cochrane review demonstrated that there is a role for St Johns wort in the management of depression and that results for St Johns wort were comparable to antidepressants with less side-effects experienced.69 Unfortunately, there is a paucity of large, randomised, placebo-controlled trials into the potential use for Hypericum in management of premenstrual dysphoric symptoms.

A small, prospective, uncontrolled, observational pilot study of 19 women with PMS had participants take 300mg of St Johns wort over 2 menstrual cycles. Response rates were recorded through self-reporting on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale and Social Adjustment scale. Results demonstrated a significant reduction in all-outcome measures with an overall improvement of 51% compared to baseline symptoms. Two-thirds of the women reported at least a 50% reduction in symptom severity with good compliance and tolerability demonstrated.70

Further large-scale, randomised placebo-controlled trials are obviously required into this area. It should be noted that St Johns wort is known to interact with a number of medications including antidepressants, anticonvulsants and the oral contraceptive pill. Side-effects include gastrointestinal symptoms, photosensitivity and skin reactions. Interestingly, the incidence of side-effects is thought to be tenfold lower than for SSRIs.66

Essence of fennel

An RCT demonstrated that both essence of fennel 2% given orally 4 hourly and mefanamic acid given 6 hourly were effective for pain relief in women with moderate to severe dysmenorrhoea, when compared with placebo.71

Evening primrose oil (EPO)

Despite widespread popularity for its use in PMS, a systematic review72 of EPO for the treatment of PMS demonstrated to be ineffective. This review commented on the poor design of the majority of the studies which had been included. The 2 most well-constructed studies included in this review were randomised cross-over or placebo-controlled, however they were small, including a total of only 76 patients. A more recent review of treatments for cyclical mastalgia found a possible role for EPO 1–3g/day, together with reducing saturated fats in the diet.13

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)

A 2009 Cochrane review into the use of TCM in management of premenstrual symptoms examined 2 large RCTs including 549 women. One of these studies was well designed and demonstrated that Jingqianping granules caused a statistically significant reduction in premenstrual symptoms. The reviewers noted, however, that the researchers provided the formula for the granules themselves and thus recommended that further trials occur to ensure that these results are reproducible.73

Physical therapies

Low-level heat therapy

Continuous low-level topical heat therapy using an abdominal patch for 12 hours was as effective as ibuprofen for the treatment of dysmenorrhoea, according to a randomised placebo and active controlled study published in Obstetrics and Gynecology in 2001.74 Therefore, topical heat packs can help alleviate dysmenorrhoea.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and acupuncture

A recent Cochrane review of 9 RCTs identified 7 involving TENS, 1 acupuncture, and 1 for both treatments.75 The author’s findings concluded that overall high frequency TENS was shown to be more effective for pain relief than placebo TENS, with insufficient evidence for low-frequency TENS.

Acupuncture

Systematic reviews of research into the use of acupuncture have been positive for a number of pain conditions including back pain, fibromyalgia and headaches. Unfortunately more evidence is required to prove benefits in premenstrual pain including dysmenorrhoea and mastalgia. A 2003 systematic review of controlled trials into the use of acupuncture and acupressure for dysmenorrhoea included 4 studies, only 2 of which were patient blinded. These studies demonstrated promising results for reduction of symptoms in patients experiencing dysmenorrhoea, however the author concluded that more comprehensive research is required.76

Spinal manipulation

A 2004 Cochrane review concluded there is no evidence that spinal manipulation is more effective than sham manipulation in the treatment of primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea.77 Five RCTs were included in this review. Interestingly, however, when the results were compared to control groups who had no treatment the author’s concluded that sham or true manipulative techniques were ‘possibly more effective’. There was no difference noted in adverse effects when the sham and true manipulation groups were compared.78

Conclusion

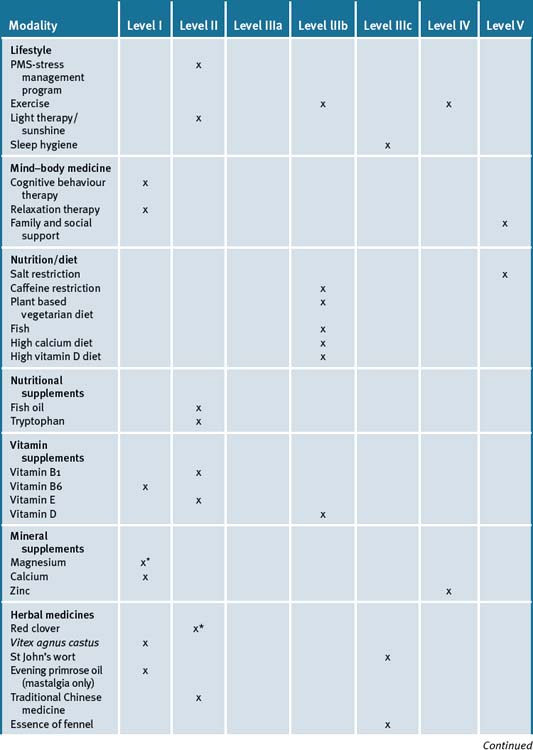

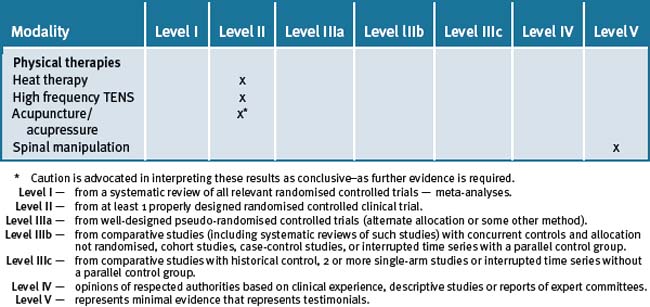

Table 33.3 is a summary of the levels of evidence for the various forms of integrative therapies outlined in this chapter.

Clinical tips handout for patients — premenstrual symptoms

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

4 Mind–body medicine

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Vitamins

Vitamin D3

Vitamin B1 and B6

Minerals

Magnesium

Calcium

Zinc

Fish oils

Herbal medicine

Red clover

Evening primrose oil

1 Collier J. SSRIs for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. 2002;40(9):70-72.

2 ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 15, April 2000. Premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:1-9.

3 Frackiewicz E.J., Shiovitz T.M. Evaluation and management of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2001 May-Jun;41(3):437-447.

4 Zaafrane F., Faleh R., Melki W., et al. An overview of premenstrual syndrome. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2007 Nov;36(7):642-652.

5 Pernol M, Benson, R. Benson and Pernoll’s handbook of obstetrics and gynaecologymcgraw Hill Publishing 2001 pp725–726.

6 Wyatt K., Dimmock P.W., O’Brien P.M. Premenstrual syndrome. In: Barton S., editor. Clinical evidence. 4th issue. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2000:1121-1133.

7 Moline M.L., Zendell S.M. Evaluating and managing premenstrual syndrome. Medscape Womens Health. 2000;5:1-16.

8 Dell D.L. Premenstrual syndrome, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and premenstrual exacerbation of another disorder. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2004;47(3):568-575.

9 Steiner M., Born L. Diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: an update. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;15(suppl 3):S5-17.

10 Limosin F., Ades J. Psychiatric and psychological aspects of premenstrual syndrome Encephale. 2001 Nov-Dec;27(6):501-508.

11 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. 717–8

12 Hillen T.I., Grbavac S.L., Johnston P.J., et al. Primary dysmenorrhea in young Western Australian women: prevalence, impact, and knowledge of treatment. J Adolesc Health. 1999 Jul;25(1):40-45.

13 Millet A.V., Dirbas F.M. Clinical management of breast pain: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002 Jul;57(7):451-461.

14 Girman A., Lee R., Kligler B. An integrative medicine approach to premenstrual syndrome [Editorial]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188(5, part 2):S56-S65.

15 Gordon N.P., Sobel D.S., Tarazona E.Z. Use of and interest in alternative therapies among adult primary care clinicians and adult members in a large health maintenance organization. West J Med. 1998 Sep;169(3):153-161.

16 Fugh-Berman A., Kronenberg F. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in reproductive-age women: a review of randomised controlled trials. Reprod Toxicol. 2003 Mar-Apr;17(2):137-152.

17 Rapkin A.. A review of treatment of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003 Aug;28 Suppl. 3:39-53..

18 Taylor D. Effectiveness of professional-peer group treatment: Symptom management for women with PMS. Nurs Health. 1999;22:496-511.

19 ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 15, April 2000. Premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:1-9..

20 Blake F., Salkovskis P., Gath D., Day A., Garrod A. Cognitive therapy for premenstrual syndrome: a controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:307-318.

21 Kessel B. Premenstrual syndrome. Advances in diagnosis and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:625-639.

22 Morse C.A., et al. A comparison of hormone therapy, coping skills training, and relaxation for the relief of premenstrual syndrome. J Behav Med. 1991 Oct;14(5):469-489.

23 Stones W., Cheong Y.C., Howard F.M. Interventions for treating chronic pelvic pain in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2005. Art. No.: CD000387. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000387

24 Proctor M.L., Murphy P.A., Pattison H.M., Suckling J., Farquhar C.M. Behavioural interventions for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2007. Art. No.: CD002248. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002248.pub3

25 Christensen A.P., Oei T.P. The efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy in treating premenstrual dysphoric changes. J Affect Disord. 1995 Jan 11;33(1):57-63.

26 Lustyk M.K., Gerrish W.G., Shaver S., Keys S.L. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009 Feb 27. [Epub ahead of print]

27 Lustyk M.K., Widman L., Paschane A., Ecker E. Stress, quality of life and physical activity in women with varying degrees of premenstrual symptomatology. Women Health. 2004;39(3):35-44.

28 Goodale I.L., Domar A.D., Benson H. Alleviation of premenstrual syndrome symptoms with the relaxation response. Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Apr;75(4):649-655.

29 Hernandez-Reif M., Martinez A., Field T., Quintero O., Hart S., Burman I. Premenstrual symptoms are relieved by massage therapy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000 Mar;21(1):9-15. PubMed PMID: 10907210

30 Driver HS, Dijk DJ, Werth E, et al. Sleep and the sleep electroencephalogram across the menstrual cycle in young healthy women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, Vol 81, 728–735.

31 Lee K.A., Shaver J.F., Giblin E.C., Woods N.F. Sleep patterns related to menstrual cycle phase and premenstrual affective symptoms. Sleep. 1990 Oct;13(5):403-409.

32 Labyak S., Lava S., Turek F., Zee P. Effects of shiftwork on sleep and menstrual function in nurses. Health Care For Women International, Volume 23, Numbers 6-7, 1. September 2002:703-714. 12

33 Baker F.C., Driver H.S. Circadian rhythms, sleep, and the menstrual cycle. Sleep Med. 2007 Sep;8(6):613-622.

34 Thys-Jacobs S., Donovan D., Papadopoulos A., et al. Vitamin D and calcium dysregulation in the polycystic ovarian syndrome. Steroids. 1999;64(6):430-435.

35 Lansdowne A.T., Provost S.C. Vitamin D3 enhances mood in healthy subjects during winter. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1998;135(4):319-323.

36 Gloth F.M.III, Alam W., Hollis B. Vitamin D vs broad spectrum phototherapy in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder. J Nutr Health Aging. 1999;3(1):5-7.

37 Al Faraj S., Al Mutairi K. Vitamin D deficiency and chronic low back pain in Saudi Arabia. Spine. 2003;28(2):177-179.

38 Thys-Jacobs S. Vitamin D and calcium in menstrual migraine. Headache. 1994 Oct;34(9):544-546.

39 Lam R.W., Carter D., Misri S., et al. A controlled study of light therapy in women with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1999 Jun 30;86(3):185-192.

40 Parry B.L., Berga S.L., Mostofi N., et al. Plasma melatonin circadian rhythms during the menstrual cycle and after light therapy in premenstrual dysphoric disorder and normal control subjects. J Biol Rhythms. 1997 Feb;12(1):47-64.

41 Hightower M. Effects of Exercise Participation on Menstrual Pain and Symptoms. Women and Health. 1998;26(4):15-27.

42 Prior J.C., Vigna Y., Alojada N. Conditioning exercise decreases premenstrual symptoms European Journal of Applied Physiology. 1986;55(4):349-355.

43 Steege J.F., Blumenthal J.A. The effects of aerobic exercise on premenstrual symptoms in middle-aged women: a preliminary study. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:127-133.

44 Prior J.C., Vigna Y., Sciarretta D., et al. Conditioning exercise decreases premenstrual symptoms: a prospective, controlled 6-month trial. Fertil Steril. 1987 Mar;47(3):402-408.

45 Deutsh B. Menstrual pain in Danish women correlated with low n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995;49:508-516.

46 Barnard N.D., Scialli A.R., Hurlock D., Bertron P. Diet and sex-hormone binding globulin, dysmenorrhea, and premenstrual symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Feb;95(2):245-250. PubMed PMID: 10674588

47 Bertone-Johnson E.R., Hankinson S.E., Bendich A., et al. Calcium and vitamin D intake and risk of incident premenstrual syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(11):1246-1252.

48 Rossignol A.M. Caffeine-containing beverages and premenstrual syndrome in young women. Am J Public Health. 1985 Nov;75(11):1335-1337.

49 Proctor M.L., Murphy P.A. Herbal and dietary therapies for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. (3):2001. CD002124

50 Whelan A.M., Jurgens T.M., Naylor H. Herbs, vitamins and minerals in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Canadian J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Fall;16(3):e407-e429. Epub 2009 Oct 29

51 High-dose vitamin B6 may cause peripheral neuropathy. ADRAC bulletin Volume 27, Number 4, August 2008 http://www.tga.gov.au/adr/aadrb/aadr0808.htm

52 Ziaei S., Zakeri M., Kazemnejad A. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin E in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005 Apr;112(4):466-469.

53 Facchinetti MD, Borella P, Sances G, et al. Oral magnesium successfully relieves premenstrual mood changes Obstetrics and Gynecology Vol. 78 n 2 1991 pp 177–181.

54 Bertone-Johnson E.R., Hankinson S.E., Bendich A., et al. Calcium and Vitamin D intake and risk of incident premenstrual syndrome Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:1246-1252.

55 Thys-Jacobs S., Starkey P., Bernstein D., et al. Calcium carbonate and the premenstrual syndrome: effects on premenstrual and menstrual symptoms. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;179:444-452.

56 Braun L., Cohen M. Herbs and Natural supplements an evidence based guide, 2nd edn. Australia: Elsevier; 2007. pp198–99

57 Eby G.A. Zinc treatment prevents dysmenorrhea. Medical Hypotheses. 2007;Volume 69(Issue 2):297-301. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.009

58 Harel Z., Biro F.M., Kottenhahn R.K., et al. Supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids in the management of dysmenorrhoea in adolescents. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;174(4):1335-1338.

59 Menkes D.B., Coates D.C., Fawcett J.P. Acute tryptophan depletion aggravates premenstrual syndrome. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1994 Mar;19(2):114-119.

60 Sayegh R., Schiff I., Wurtman J., Spiers P., McDermott J., Wurtman R. The effect of a carbohydrate-rich beverage on mood, appetite, and cognitive function in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Oct;86(4 Pt 1):520-528.

61 Sayegh R., Schiff I., Wurtman J., et al. The effect of a carbohydrate-rich beverage on mood, appetite and cognitive function in women with premenstrual syndrome. J Affect Disord. 1994 Sep;32(1):37-44.

62 FDA/DFSAN information paper on L-tryptophan Feb 2001 http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/∼dms/ds-tryp1.html

63 Ingram D.M., Hickling C., West L., et al. A double-blind randomised controlled trial of isoflavones in the treatment of cyclical mastalgia. Breast. 2002 Apr;11(2):170-174.

64 Berger D., Schaffner W., Schrader E., et al. Efficacy of Vitex agnus castus L. extract Ze 440 in patients with pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS). Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2000 Nov.;264(3):150-153.

65 Schellenberg R. Treatment for the Premenstrual Syndrome With Agnus Castus Fruit: Prospective, Randomised, Placebo Controlled Study. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:134-137.

66 Carmichael A.R. Can Vitex Agnus Castus be used for the treatment of cyclical mastalgia? What is the current evidence? eCAM. 2008;5(3):247-250.

67 Atmaca M., Kumru S., Tezcan E. Fluoxetine versus Vitex Agnus Castus Extract in the Treatment of Premestrual Disphoric Disorder. Human Psychopharmacology. 2003 Apr;18(3):191-195.

68 Braun L., Cohen M. Herbs and natural supplements. An evidence based guide, 2nd edn. Elsevier; 2007. pp 551–553

69 Linde K., Berner M.M., Kriston L. St John’s wort for major depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2008. Art. No.: CD000448. DOI: 0.1002/14651858.CD000448.pub3

70 Stevinson C., Ernst E. A pilot study of Hypericum perforatum for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Altern Complement Med. 2004 Dec;10(6):925-932.

71 Namavar Jahromi B., Tartifizadeh A., Khabnadideh S. Comparison of fennel and mefenamic acid for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003 Feb;80(2):153-157.

72 Budeiri D., Li Wan Po A., Dornan J.C. Is evening primrose oil of value in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:60-68.

73 Jing Z., Yang X., Ismail K.M., Chen X., Wu T. Chinese herbal medicine for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2009 Jan 21. CD006414. Review. PubMed PMID: 19160284

74 Akin M.D., Weingand K.W., Hengehold D.A., et al. Continuous low-level topical heat in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Mar;97(3):343-349.

75 Proctor M.L., Smith C.A., Farquhar C.M., Stones R.W. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhoea (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. (Issue 3):2005.

76 White A.R. A review of controlled trials of acupuncture for women’s reproductive health care. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2003 Oct;29(4):233-236.

77 Proctor M.L., Hing W., Johnson T.C., Murphy P.A. Spinal manipulation for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. The Cochrane library. (Issue 1):2004.