Chapter 37 Premalignant and malignant conditions of the female genital tract

CERVICAL PRECANCER AND CANCER

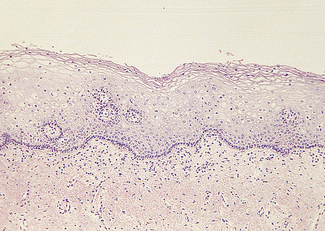

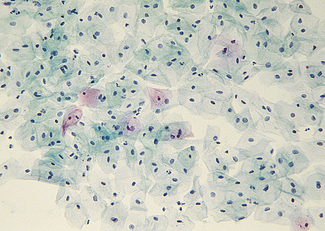

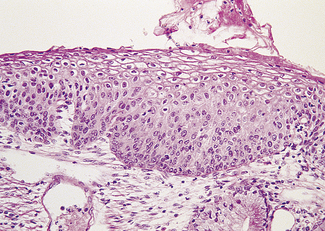

The cervical epithelium undergoes changes throughout the menstrual cycle and is readily accessible for examination. The epithelium covering the ectocervix is stratified and identical to that of the vagina (Fig. 37.1). It is separated from the underlying stroma by an apparent basement membrane. Superior to this is a layer of basal cells from which the other cell layers differentiate. Above the basal layer are five or six layers of parabasal cells. Above these are intermediate and superficial cell layers. The intermediate cell layer consists of large cells, each with reticulated nuclei and vacuoles of glycogen in the cytoplasm. The superficial cell layer varies in thickness, depending on the oestradiol : progesterone ratio. The superficial cells are flattened and have small nuclei, the cytoplasm containing glycogen (Fig. 37.2). A small amount of keratin is produced in some of the cells, which becomes ‘cornified’. During the reproductive years the superficial cells are constantly shed or exfoliated into the vagina, and differentiation of cells from the basal layer also proceeds constantly.

Epidemiology of cervical cancer

Cervical cancer occurs almost exclusively in women who are or have been sexually active. There is strong molecular biological and epidemiological evidence that the predominant cause of cervical cancer is sexually transmitted human papilloma virus (HPV). There are four HPV types that are considered to be high risk (16, 18, 45 and 56), a further 11 types that are intermediate risk (31, 33, 35, 39, 51, 52, 55, 58, 59, 66 and 68) and eight that are low risk (6, 11, 26, 42, 44, 54, 70 and 73) By the age of 35, 60% of sexually active women have acquired HPV infection of the genital tract (including the vulva). This proportion is higher if the woman or her partner has had several sexual partners. In most cases the infection is symptomless and disappears within a few months (see p. 258).

Cervical exfoliative cytology

The recommended smear regimen is summarised in Box 37.1. In women aged 30 and over, the doctor or nurse taking the smear should also examine the woman’s breasts, teach her breast self-examination, and after the age of 40 measure her blood pressure.

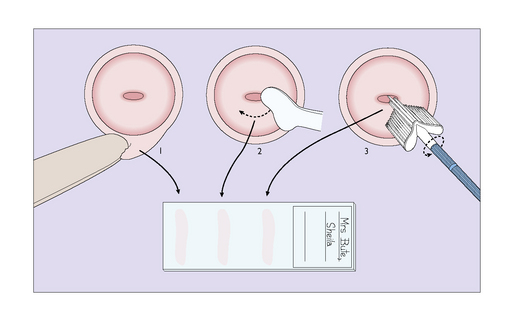

Technique for taking a cervical smear

A tray is provided on which a bivalve vaginal speculum, some slides, a spray-on fixative plastic, a modified Ayre spatula and an endocervical brush are placed. Before performing a vaginal examination, the warmed speculum is inserted to expose the cervix. The cytobrush is inserted into the cervical canal and rotated. The sample is smeared on to the slide. The ectocervix is sampled with the Ayre spatula or Cervex brush by rotating it twice through 360° and the sample is smeared on to a slide (Fig. 37.3). If liquid-based cytology is being used the brush is placed in the liquid medium.

The smears are sent to a reliable, quality assured cytological laboratory for examination.

REPORTING ON SMEARS

The Bethesda Classification

Squamous cell

New cervical screening techniques

Management of abnormal cervical smears

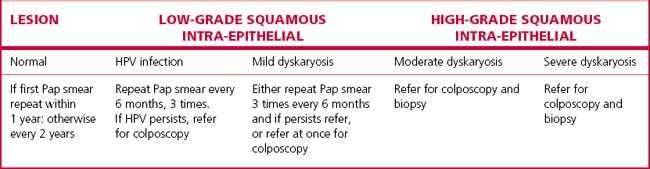

Approaches to the management of abnormal cervical smears are summarized in Table 37.1.

Mild dyskaryosis (predictive of CIN 1) with or without HPV

There are three potential management options:

Consequently the National Health and Medical research Council of Australia recommends option 1.

Colposcopy

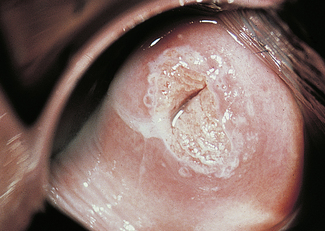

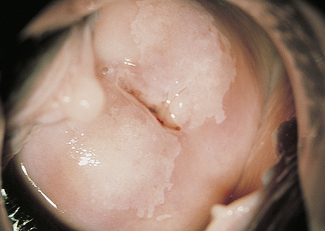

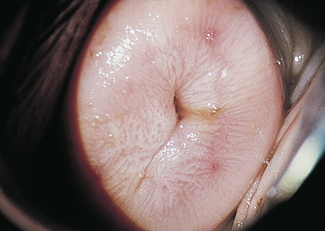

Dyskaryosis is a cytological diagnosis and observer error is not uncommon. For this reason, a colposcope is often used to verify abnormal findings. A colposcope is a system of lenses that magnifies the cervix 5–20 times and enables a trained observer to translate changes in colour tone, opacity, surface configuration, vascular pattern and intercapillary distance into a diagnosis (Figs 37.5–37.8).

Abnormal epithelium is white after the application of aqueous acetic acid solution (acido-white epithelium), white keratotic patches may be seen (Fig. 37.6), and the blood vessels may appear as punctate dots or as a mosaic arrangement. Bizarre branching vessels usually denote invasive cancer. A trained observer can differentiate between the minor and major cervical precancer lesions and carcinoma with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The predicted diagnosis is confirmed by punch biopsies, which are examined histologically.

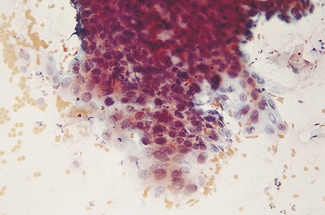

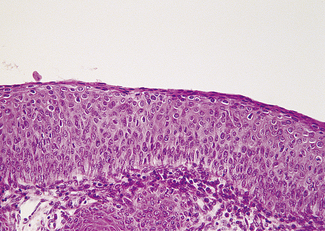

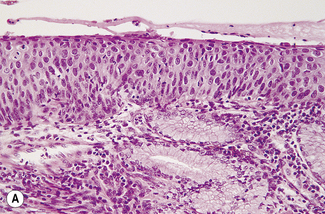

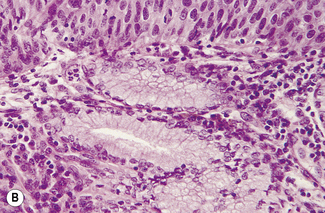

Histology

Mild dysplasia is characterized by nuclear abnormalities in the basal third of the epithelium; the upper layers are not affected. In moderate dysplasia some dyskaryotic nuclei are found in the upper layers of the epithelium, and abnormal nuclei are more common (Fig. 37.9). In severe dysplasia the abnormal nuclei occupy all the epithelial layers and there is a high nuclear : cytoplasmic ratio (Fig. 37.10). Severe dysplasia may be difficult to differentiate from carcinoma in situ. In carcinoma in situ there is no differentiation as the surface layers are reached; the nuclei vary in size and stain deeply, the cells are crowded and the cytoplasm is scanty (Fig. 37.11).

Fig. 37.11 Cervical biopsy from the patient whose cervical smear is shown in Fig. 37.4. Carcinoma in situ was found. (A) (× 40). There appears to be invasion of the tissues, but in reality the cells have only crept into endocervical crypts. (B) (× 160). The lack of stratification and pleomorphism of the cells is seen at higher magnification.

CERVICAL INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASIA (CIN)

In some cases there is uncertainty about the exact histological diagnosis and whether the identified lesion will regress, persist or progress. This has led to a classification that includes all grades of dysplasia, the CIN classification (Table 37.2).

| GRADE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Mild dysplasia |

| Grade 2 | Moderate dysplasia |

| Grade 3 | Severe dysplasia/Carcinoma in situ |

Natural history of CIN

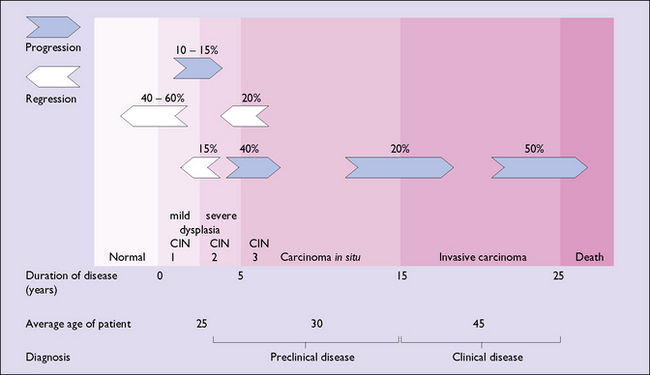

The current belief about the natural history of CIN is shown in Figure 37.12.

CERVICAL CARCINOMA

Accurate staging of the disease is critical to determine the optimal mode of treatment, and the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (FIGO) classification is summarized in Table 37.3. The higher the stage on the initial examination, the greater the chance of lymph node involvement and the poorer the prognosis (Table 37.4). In early-stage disease (stages 1B and 2A, see later) lymph node metastases are present in 25–30% of cases.

Table 37.3 International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (FIGO) classification for staging of carcinoma of uterine cervix

| STAGE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (CIN 3), Carcinoma in situ |

| Stage 1 | The carcinoma is confined to the cervix |

Table 37.4 Lymph node involvement and 5-year survival rates of cervical carcinoma related to stage of the disease

| STAGE | LYMPH NODE INVOLVEMENT | 5-YEAR SURVIVAL (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 1A | 0.5 | 95 |

| 1B | 15 | 80 |

| 2A | 25 | 66 |

| 2B | 35 | 64 |

| 3 | 55 | 35 |

| 4 | >65 | 14 |

ENDOMETRIAL CARCINOMA

Endometrial carcinoma is a disease of women in their middle years, the peak incidence occurring in the 55–65-year age group. Women whose menopause is delayed beyond the age of 55, who are relatively infertile, and overweight or hypertensive are more likely than other women to develop endometrial cancer. This profile suggests that unopposed oestrogen may play a role in the development of the cancer. As discussed on page 297, unopposed oestrogen may lead to endometrial hyperplasia (Fig. 37.13). Endometrial hyperplasia has several pathological appearances, and if the pathology shows complex hyperplasia with atypia 17–43% of women will develop endometrial cancer, unless they are treated.

The tumour may originate in any part of the endometrium, and grows slowly, tending to spread over a part of the endometrium before invading the myometrium. If the growth starts in the lower part of the uterus, the fungating mass may block the cervix and fluid or pus may collect in the uterus (pyometra). Various histological patterns of adenocarcinoma are found on the histological examination of an endometrial biopsy or curettage. The more undifferentiated the endometrial cells, the worse the prognosis. The cancer is staged using the FIGO classification (Table 37.5).

Table 37.5 Surgical–pathological staging of endometrial carcinoma (FIGO, 1989)

| STAGE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| IA | Tumour limited to endometrium |

| IB | Invasion to <1/2 myometrium |

| IC | Invasion to >1/2 myometrium |

| IIA | Endocervical glandular involvement only |

| IIB | Cervical stromal invasion |

| IIIA | Tumour invades serosa and/or adnexae and/or positive peritoneal cytology |

| IIIB | Vaginal metastases |

| IIIC | Metastases to pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes |

| IVA | Tumour invades bladder and/or bowel mucosa |

| IVB | Distant metastases including intra-abdominal and/or inguinal lymph node |

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the stage of the disease, the histological grade of the tumour and the age and health of the woman (Table 37.6).

Table 37.6 The recommended treatment and 5-year survival rate of endometrial cancer related to the stage of the disease

| STAGE | RECOMMENDED TREATMENT | 5-YEAR SURVIVAL RATE (%) |

|---|---|---|

| IA | Hysterectomy | 90 |

| IB | Hysterectomy | 88 |

| IC | Hysterectomy followed by vaginal vault and pelvic irradiation | 80 |

| IIA | As for carcinoma of cervix | 77 |

| II B | As for carcinoma of cervix | 67 |

| III | Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy if feasible plus radiation therapy | 40 |

| IV | Palliative surgery, radiation therapy and progestogenic therapy | 10 |

VULVAL DISEASE

Carcinoma of the vulva

Clinical

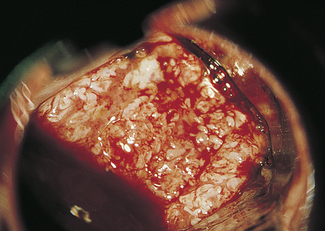

The lesion presents as a hard nodule or an ulcer with a sloughing base and raised edges, which may be small or large depending on the duration of the disease (Fig. 37.14). If the cancer is large, lymph node involvement will have occurred in more than 50% of cases.

The overall 5-year survival is 70%; for stage I 90%, stage II 75%, stage III 50%, and stage IV 15%.

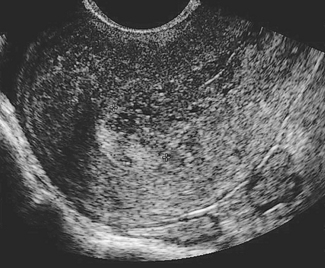

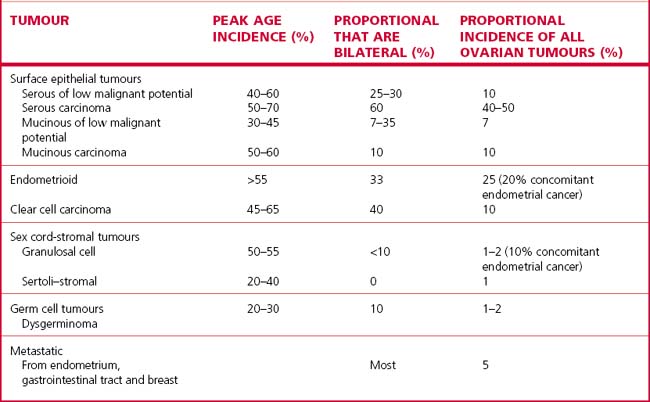

CANCER OF THE OVARY FOLLOWED BY ULTRASOUND (FIG. 37.15)

The tumour may arise in several ways, as shown in Table 37.7.

Clinical features

The woman, who is usually aged 50 or more, may notice that her abdomen is becoming larger (from the mass, or from ascites), or she may complain of pressure symptoms on her bladder or rectum. Abdominal discomfort and gastrointestinal symptoms may be present. She may have lost weight and have a poor appetite. In most cases the symptoms are few if any and the tumour is detected during a routine examination Germ cell malignancies can affect women under the age of 30, the most common being dysgerminoma. The FIGO staging of ovarian cancer is shown in Table 37.8.

Table 37.8 FIGO staging and 5-year survival of ovarian cancer

| STAGE | 5-YEAR SURVIVAL (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Growth limited to ovaries | 85 |

| II | Growth involving 1 or both ovaries with pelvic extension | 60 |

| III | Peritoneal implants outside the pelvis | 30 |

| IV | Distant metastases | 10 |

VAGINAL CANCER

Upper vaginal tumours are treated as for cervical carcinoma and lower tumours by radiotherapy.

The 5-year survival is poorer than for cervical and vulval carcinoma, being around 45%.

PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS OF GYNAECOLOGICAL CANCER

During and after treatment for gynaecological cancer many women become depressed, which may adversely affect their relationship with their partner. Surgery of the genital tract, especially if it involves the vagina or vulva, threatens the woman’s identity. Her vagina may be shortened, her vulva mutilated, she may no longer lubricate when sexually stimulated, and she may perceive sexual activity as inappropriate. Her husband may be concerned that sexual intercourse may damage her or lead to his developing cancer. He may find difficulty in accepting his ‘mutilated’ wife as a sexual partner. Women who have cervical cancer may be concerned that the disease is a result of her or her partner’s past sexual behaviour (see pp. 292, 295). These feelings are commonly associated with reduced or absent sexual desire.