CHAPTER 10 PREHOSPITAL AIRWAY MANAGEMENT: INTUBATION, DEVICES, AND CONTROVERSIES

Prehospital trauma airway management is probably the biggest challenge faced by prehospital providers. These professionals must not only acquire but also maintain essential skills to adequately manage airway problems at the scene and during transport of trauma victims to trauma centers.

WHO NEEDS AN AIRWAY?

In trauma, it has been shown that moribund patients would benefit from an airway, particularly those who are candidates for a resuscitative thoracotomy upon arrival at the hospital.1

DIFFICULT AIRWAY

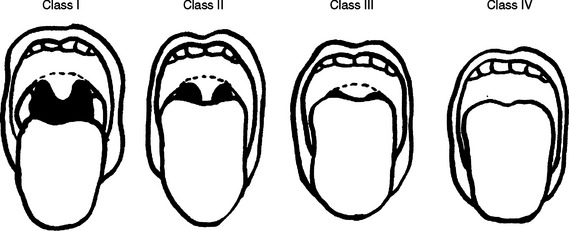

The Mallampati classification has been used for many years by anesthesiologists during preoperative evaluations for the identification of a difficult airway and to predict difficult intubation2 (Figure 1). It compares tongue size with the oropharyngeal space, and its reliability has been questioned because it does not take into account other factors that may make intubation difficult or impossible in the prehospital setting. However, if the patient is still able to follow simple commands, direct visualization of the oropharynx by asking the patient to open the mouth will give additional and important information to the astute prehospital provider. Rich3 described the 6-D methods of airway assessment: disproportion; distortion; decreased thyromental distance; decreased interincisor gap; decreased range of motion in any or all of the joints—atlanto-occipital, temporomandibular, and cervical spine, always present in trauma; and dental overbite.

WHICH STRATEGY SHOULD BE USED?

Laryngeal Mask Airway

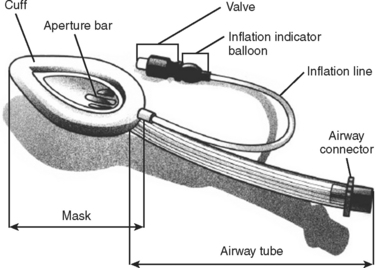

The LMA is one alternative to endotracheal intubation (Figure 2). Its use is particularly important in patients with difficult airways (defined later) and in patients treated in “unfriendly” environments (rain, dark, prolonged extrication, etc.). It also can be used as a rescue strategy following a failed RSI. Additionally, it can be used to facilitate intubation, which is obtained by passing the endotracheal tube through the LMA.

The insertion of the LMA is done blindly into the oropharynx, and it is usually tolerated without the need of neuromuscular blockade. The LMA lies in the hypopharynx in the supraglottic position. The successful placement of the LMA is independent of the Mallampati score, presence of a C-collar, or in-line immobilization of the neck. Spontaneous ventilation through the LMA is possible, and manual ventilation through the LMA is superior to bag-valve-mask ventilation, because the latter requires two hands to maintain a good seal. Studies comparing the success rates have shown that paramedics achieve higher levels of successful placement with the LMA compared to endotracheal intubation.4 The LMA may be particularly useful in patients with a difficult airway, since direct visualization of the cords is not required and neuromuscular blocking agents are not necessary. The advantages of the LMA over the Combitube (described next) include lower risk of malpositioning, no risk of esophageal intubation, and less trauma to the oropharynx. A major disadvantage of the LMA is that it does not protect against aspiration, which may carry significant risk in patients with intact airway reflexes. Another limitation of LMA is related to the difficulty in generating high airway pressures, which may lead to ineffective ventilation.5

Combitube

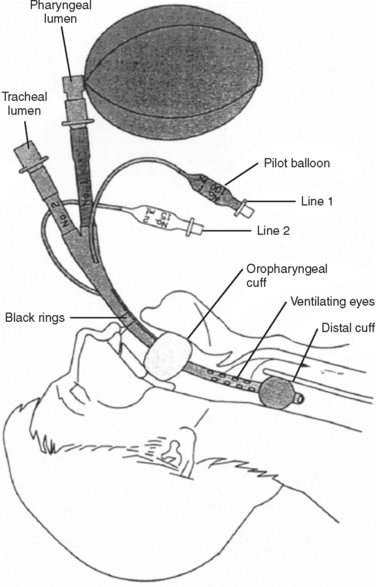

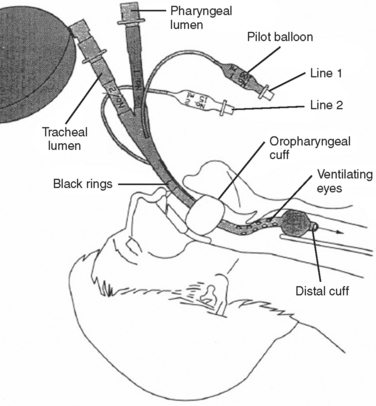

The Combitube consists of a device with two lumens. One of the lumens has an open distal end similar to an endotracheal tube, whereas the other lumen has a closed distal end, with several holes proximal to its balloon cuff. A second balloon of higher volume is located more proximally to the side holes, and it is used to secure the tube in position. The Combitube is inserted blindly and allows ventilation through either lumen. Following blind insertion, the distal tip is usually located in the esophagus. After inflating the oropharyngeal balloon, the esophageal cuff is inflated. Attempts to ventilate through the pharyngeal lumen will determine whether the distal tip is in the esophagus or trachea. If there is no change in the colorimetric, end-tidal carbon dioxide detector, or if breath sounds are absent, then the distal tip is in the trachea and the patient should be ventilated through the tracheal lumen (Figures 3 and 4).

Orotracheal Intubation

Endotracheal intubation (ETI) is the gold standard of airway management. In the prehospital setting, endotracheal intubation without the use of sedatives or neuromuscular blockade is only achievable in obtunded patients. Because few systems allow paramedics to use RSI, and based on the fact that obtunded patients carry a poor prognosis, endotracheal intubation in those situations may cause more harm than good. Without ideal conditions, endotracheal intubation may be accompanied by an increased number of complications, including hypoxemia, esophageal intubation, and intubation of the mainstem bronchus, with subsequent complete lung collapse, injury to the oropharynx, regurgitation, exacerbation of a potential spinal cord injury, circulatory compromise, increased intracranial pressure, and delay in transport to a trauma center, just to name a few. Inability to recognize a difficult airway may make the intubation impossible and if preceded by RSI may lead to devastating complications and eventually death. Common pitfalls of endotracheal intubation will be discussed.

Confirmation of Orotracheal Tube Placement

The colorimetric, end-tidal carbon dioxide detector has been used by prehospital personnel to confirm endotracheal tube placement. In the presence of high levels of carbon dioxide, the device changes color from purple to yellow. The device has been deemed reliable; however, it lacks sensitivity in the setting of cardiopulmonary arrest due to the lack of pulmonary blood flow limiting carbon dioxide delivery. Therefore, approximately 15% of patients properly intubated in that setting would have their endotracheal tubes removed based on the lack of color change in the device.6 The opposite is also true, and a color change may be observed in patients who have ingested large volumes of carbonated liquids (beer, sodas, etc.), when the tube is in the esophagus or when the stomach has been insufflated with expired gas during bag-valve-mask ventilation.

CONTROVERSIES IN PREHOSPITAL INTUBATION

Prehospital Intubation in Traumatic Brain Injury

While an aggressive approach to airway management including ETI is standard-of-care for patients with severe TBI, it is notable that there is little evidence to support this approach.7 In fact, several recent studies have demonstrated an increase in mortality associated with prehospital intubation.8–10 It is not clear whether this represents a selection bias or a true detrimental effect of invasive airway management on outcome. The purported benefits of early intubation include reversal of hypoxia and airway protection from aspiration. However, the morbidity and mortality associated with these secondary insults may not be preventable or reversible with invasive airway management 10–15 minutes after the initial injury.11 In addition, there has been a recent increase in awareness of the adverse effects of positive-pressure ventilation on outcome, especially with hyperventilation and hypocapnia.

This makes patient selection for early intubation extremely important so as to maximize the benefit of the procedure. The use of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score alone to select patients to undergo prehospital intubation has several limitations. An early GCS score appears to have only moderate specificity in identifying severe TBI.12 In addition, the relationship between GCS score and aspiration is indirect at best. Aspiration events may occur prior to arrival of EMS personnel or with manipulation of laryngeal structures during intubation.11 Furthermore, hypoxemia may be reversible with noninvasive airway maneuvers, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) values with supplemental oxygen may be an important factor in considering prehospital intubation.13 While no study has clearly defined a subgroup of head-injured patients who should undergo early intubation, neural network analysis using data from our trauma registry suggests that the most critically injured patients, as defined by GCS score and the presence of hypotension, benefit from the procedure. In addition, intubation does provide additional benefit with regard to the reversal of hypoxemia in some patients.3,13

Who Should Perform Prehospital RSI?

The San Diego Paramedic RSI Trial prospectively enrolled severe TBI patients who could not be intubated without medication. The primary outcome analyses compared trial patients with non-intubated historical controls matched for age, gender, mechanism, trauma center, and body region Abbreviated Injury Scores. Despite a substantial increase in the percentage of patients arriving with an invasive airway, trial patients had higher mortality and a lower incidence of good outcomes.14 Subsequent analyses suggest that suboptimal performance of the procedure, including hyperventilation and deep desaturations, accounts for at least part of the mortality increase.13 This may reflect the inexperience of paramedics in that system with regard to RSI and the limitations of a single, 8-hour training session.

Other systems providing more intensive training have documented improved success rates, although the link between experience and performance of RSI remains unclear.15 In the San Diego study, the only subgroup with improved outcomes versus matched historical controls was the group undergoing RSI by paramedics then transported by air medical crews.13,14 The low incidence of hyperventilation in this cohort may explain this somewhat unexpected finding. Subsequent analyses from San Diego and from Pennsylvania document worse outcomes with paramedic intubation but improved outcomes with air medical RSI as compared to emergent intubation in the ED.8,16 Together, these studies suggest that prehospital RSI may be efficacious when performed by experienced, highly trained individuals. The extent and frequency of initial and ongoing training remains to be defined.

Role of Capnometry in Prehospital Intubation

Quantitative capnometry has several advantages in the management of brain-injured patients. First, capnometry offers accurate confirmation of endotracheal tube placement, both at the time of initial intubation and continuously throughout the prehospital course. Clearly, early recognition of a misplaced endotracheal tube can avoid serious morbidity and mortality. Systems that have instituted quantitative capnometry as the “gold standard” for endotracheal tube placement have reported unrecognized esophageal intubation rates approaching zero.17

Perhaps equally important to the TBI patient is the ability of capnometry to guide ventilation. Data from the San Diego Paramedic RSI Trial established the importance of avoiding hyperventilation and demonstrated the ability of quantitative capnometry to avoid hyperventilation based on arrival pCO2 value.13,18 There does appear to be a learning curve, however, as air medical crews who had used capnometry to guide ventilation for many years had better end-tidal carbon dioxide and arrival pCO2 values than paramedics using capnometry.18 It is our belief that quantitative capnometry should be the standard of care for management of intubated patients in the prehospital environment, especially those with TBI who are especially susceptible to secondary insults.

Use of Positive End-Expiratory Pressure

While avoiding hyperventilation may be the most important lesson of the San Diego Paramedic RSI Trial, it is possible that invasive airway management is inherently detrimental due to a combination of barotrauma and “atelectrauma,” which results from complete alveolar closure with each breath when positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is not applied. Experimental data suggest detrimental immunologic and structural effects with “injurious” ventilation, defined as 10–12 cc/kg without PEEP.19 In addition, PEEP may enhance alveolar recruitment and improve oxygenation, making it preferable to the use of hyperventilation to reverse hypoxemia. However, PEEP also appears to result in adverse hemodynamic effects in hypovolemic patients.18 This is an area requiring additional study before a final verdict on the use of PEEP can be rendered.

FINAL COMMENTS

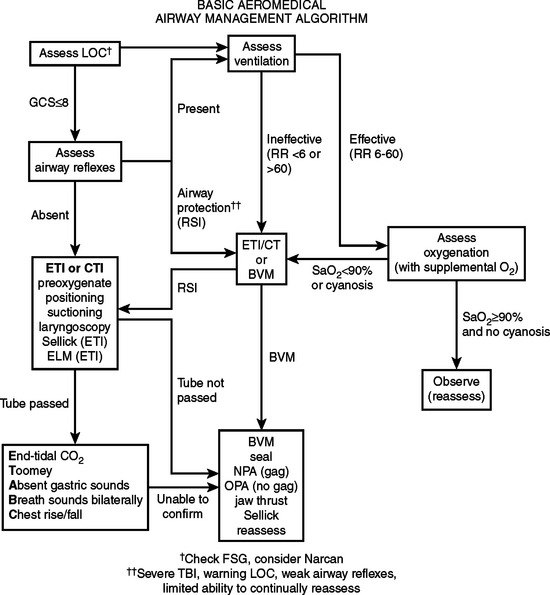

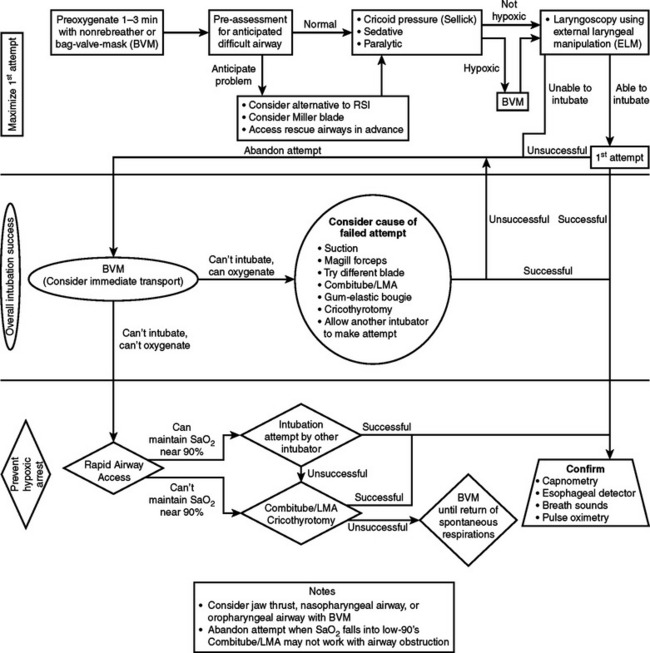

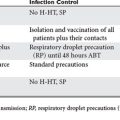

Prehospital airway management is a difficult task that requires training and skills. Endotracheal intubation remains the gold standard of airway management. Specific strategies need to be in place for basic and advanced units (Figures 5 and 6). Higher success rates will be achieved if endotracheal intubation is attempted after the use of rapid sequence analgesia and paralysis; however, most ground units are not prepared and are not allowed to use such strategy. On the other hand, most aeromedical transport units are facile with RSI and employ this strategy with marked success. A successful RSI program requires medical direction and supervision, training and continuing education, resources for patient monitoring, drug storage and delivery, conformation and monitoring of endotracheal tube placement, standardized protocols, back-up airway methods, and continuing quality assurance and performance review.20

1 Durham LA, Richardson RJ, Wall MJ, et al. Emergency center thoracotomy: Impact of prehospital resuscitation. J Trauma. 1992;32:775-779.

2 Samsoon GLT, Young JRB. Difficult tracheal intubations. Anesthesia. 1987;42:487-490.

3 Rich JM. Recognition and management of the Difficult airway with special emphasis on the intubating LMA-Fastrach/whistle technique: a brief review with case reports. Baylor Univ Med Ctr Proc. 2005;18:220-227.

4 Deakin CD, Peters R, Tomlinson P, et al. Securing the pre-hospital airway: a comparison of laryngeal mask insertion and endotracheal intubation by UK paramedics. Emerg Med J. 1995;22:64-67.

5 Hulme J, Perkins GD. Critical injured patients, inaccessible airways, and laryngeal mask airways. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:742-744.

6 Bhende MS, Thompson AE. Evaluation of an end-tidal carbon dioxide detector during pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Pediatrics. 1995;95:395-399.

7 Walls RL. Rapid-sequence intubation in head trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(6):1008-1013.

8 Wang HE, Peitzman AD, Cassidy LD, et al. Out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation and outcome after traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(5):439-450.

9 Davis DP, Peay J, Sise MJ, et al. The impact of prehospital endotracheal intubation on outcome in moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2005;58:933-939.

10 Bochicchio GV, Ilahi O, Joshi M, et al. Endotracheal intubation in the field does not improve outcome in trauma patients who present without lethal traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2003;54(2):307-311.

11 Atkinson JLD. The neglected prehospital phase of head injury: apnea and catecholamine surge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:37-47.

12 Bazarian JJ, Eirich MA, Salhanick SD. The relationship between pre-hospital and emergency department Glasgow coma scale scores. Brain Inj. 2003;17(7):553-560.

13 Davis DP, Dunford JV, Poste JC, et al. The impact of hypoxia and hyperventilation on outcome after paramedic rapid sequence intubation on severely head-injured patients. J Trauma. 2004;57:1-10.

14 Davis DP, Hoyt DB, Ochs M, et al. The effect of paramedic rapid sequence intubation on outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2003;54(3):444-453.

15 Wayne MA, Friedland E. Prehospital use of succinylcholine: a 20-year review. Prehosp Emerg Care. 1999;3(2):107-109.

16 Davis DP, Peay J, Serrano JA, et al. The impact of aeromedical response to patients with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(1):1-8.

17 Silvestri S, Ralls GA, Krauss B, et al. The effectiveness of out-of-hospital use of continuous end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring on the rate of unrecognized misplaced intubation within a regional emergency medical services system. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:497-503.

18 Davis DP, Dunford JV, Ochs M, et al. The use of quantitative end-tidal cap-nometry to avoid inadvertent severe hyperventilation in patients with head injury after paramedic rapid sequence intubation. J Trauma. 2004;56:808-814.

19 Slutsky AS, Ranieri VM. Mechanical ventilation: lessons from the ARDSNet trial. Respir Res. 2000;1:73-77.

20 Swanson ER, Fosnocht DE, Barton ED. Air medical rapid sequence intubation: how can we achieve success? Air Med J. 2005;24:40-46.