CHAPTER 14 Pregnancy: Second Trimester

HEARTBURN (GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX) IN PREGNANCY

Heartburn is caused by a reflux of gastric acids into the lower esophagus, usually occurring after meals or when lying down.1 The gastric acids irritate the esophagus, causing a burning sensation behind the sternum that may extend into the neck and face, and may be accompanied by regurgitation, nausea, and hypersalivation. Inflammation and ulceration of the esophagus may result.2 Up to two-thirds of women experience heartburn during pregnancy.3 Only rarely it is an exacerbation of pre-existing disease. Symptoms may begin as early as the first trimester and cease soon after birth. Most women first experience reflux symptoms after 5 months of gestation; however, many women report the onset of symptoms only when they become very bothersome, long after the symptoms actually began.3 The prevalence and severity of heartburn progressively increases during pregnancy.4

The exact causes(s) of reflux during pregnancy include relaxed lower esophageal tone, secondary to hormonal changes during pregnancy, particularly the influence of progesterone, and mechanical pressure of the growing uterus on the stomach which contributes to reflux of gastric acids into the esophagus.3 However, some studies have demonstrated that, in spite of increased intra-abdominal pressure as the uterus expands as pregnancy progresses, the high abdominal pressure and the low pressure in the esophagus are maintained by a compensatory increase in lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure, supporting the finding by Lind et al. that the LES pressure rose in response to abdominal compression in pregnant women without heartburn.3 Other possible contributing factors include an alteration in gastrointestinal transit time. For example, some studies have suggested that ineffective esophageal motility (decreased amplitude of distal esophageal contractions) is the most common motility abnormality in GERD.5

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

Medical treatment in pregnancy focuses on symptomatic relief. Complications due to reflux in pregnancy are rare because of its short duration, and thus upper endoscopy and other diagnostic tests are not typically indicated.3 Complications, however, can include esophagitis, bleeding, and stricture formation. Care should follow a “step-up algorithm” (start with simple and noninterventional strategies and add on as needed) beginning with lifestyle modifications and dietary changes. Antacids or sucralfate are considered the first-line drug therapies. If symptoms persist, histamine-2-receptor (H2) antagonists can be used. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are reserved for women with intractable symptoms or complicated reflux disease. Promotility agents may also be used. All but omeprazole are FDA category B drugs during pregnancy. Most drugs are excreted in breast milk. Of systemic agents, only the H2 receptor antagonists, with the exception of nizatidine, are safe to use during lactation.3

There are limited data regarding the safety of antacids during pregnancy, and teratogenicity is a significant concern.3 One retrospective case controlled study in the 1960s reported a significant increase in major and minor congenital abnormalities in infants exposed to antacids during the first trimester of pregnancy.3 Analysis of individual antacids has shown no such associations, and most aluminum-, magnesium-, and calcium-containing antacids are considered acceptable in normal therapeutic doses during pregnancy.3 One study “found a higher rate of congenital anomalies in children of women who took an antacid in the first trimester.”6 Side effects of antacids are diarrhea, constipation, headaches, and nausea. Compounds containing magnesium trisilicate can lead to fetal nephrolithiasis, hypotonia, respiratory distress, and cardiovascular impairment if used long-term and in high doses. Magnesium sulfate can slow or arrest labor and may cause convulsions. Magnesium-containing antacids should be avoided during the last few weeks of pregnancy. Antacids containing sodium bicarbonate should not be used during pregnancy because they can cause maternal or fetal metabolic alkalosis and fluid overload. Pregnant women receiving iron for iron deficiency anemia should be monitored carefully when antacids are used, because normal gastric acid secretions facilitate the absorption of iron, and iron and antacids should be taken at different times during the day to avoid problems.3 There are also little data to support the efficacy of antacids during pregnancy.6

Medications for treating GERD are not routinely or rigorously tested in randomized, controlled trials in pregnant women because of ethical and medicolegal concerns. Most recommendations arise from case reports and cohort studies by physicians, pharmaceutical companies, or the FDA. Voluntary reporting by the manufacturers suffers from an unknown duration of follow up, absence of appropriate controls, and possible reporting bias.3

Some believe that over-the-counter antacids should be avoided in pregnancy because they can lead to an excess intake of aluminum and salt and interfere with absorption of potassium, phosphorus, and calcium and drugs such as anticoagulants, salicylates, and vitamin E.7 One small double-blind randomized control trial in pregnancy was identified for H2-blockers. It found that 150 mg of Ranitidine taken twice daily improved symptoms over a placebo by 44% and supposedly demonstrated no risk. However, it mirrored the antacid alone group, which also had reduced symptoms of 44%.8

BOTANICAL TREATMENT

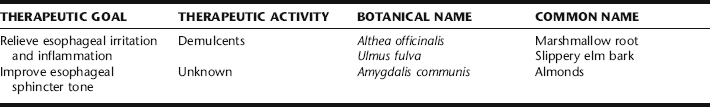

Herbal treatment for heartburn during pregnancy focuses on simple lifestyle and dietary modification, and the use of gentle herbs to soothe and protect the esophageal epithelium (Table 14-1). A mild antacid herb may also be included in more bothersome cases. Nervines (e.g., chamomile, skullcap, or passion flower) can be added to a protocol if heartburn is causing sleeping problems or if stress is contributing to digestive difficulties. Herbs for treating heartburn are best taken as teas or lozenges (e.g., slippery elm bark lozenges) rather than as tinctures, both to bathe the alimentary canal as they are ingested, and avoid the potentially irritating effects of alcohol in the tinctures. Further, demulcent herbs are best extracted in water for maximum efficacy (see Chapter 3).

General Recommendations for Preventing/Relieving Heartburn

Other practices may help to improve symptoms:

Interestingly, almost no clinical trials have been conducted demonstrating beneficial effects of eliminating offending foods or practices, including those listed in the preceding, with the exception of elevation of the head of the bed.12 Nonetheless, many women report improvement with a combination of these changes.

Discussion of Botanicals

Almonds

Chewing raw almonds is a treatment relied on by many midwives for the reduction of heartburn. Instruct clients to thoroughly chew 8 to 10 raw almonds and swallow. This may be repeated several times daily. Almonds are nutritive and there are no expected side effects or contraindications to the use of this food.

Marshmallow Root

Marshmallow root has similar properties to slippery elm—it is mucilaginous, soothing, and anti-inflammatory to epithelial surfaces. Evidence for the use of this herb stems largely from traditional use. Though this herb has been used for centuries, there are remarkably few clinical trials evaluating its safety or efficacy. It has no known expected toxic effects; however, it has been shown to lower blood sugar in animal studies. Caution should be observed when using this herb in combination with blood sugar lowering medications, though the risk is theoretical. It has been suggested theoretically that this herb might interfere with drug absorption. Although this has never been demonstrated clinically, it may be prudent to avoid taking this herb at the same time as taking other medicinal agents, and instead take marshmallow root and other medications several hours apart.13 Herbalists, however, commonly combine marshmallow with other herbs for the digestive tract. Unlike slippery elm, marshmallow is not available in convenient lozenges; therefore, it must be prepared as an infusion, and sipped as needed throughout the day or during an acute episode of heartburn.

Slippery Elm

Ulmus rubra is a nutritive demulcent, rich in mucilaginous polysaccharides. Slippery elm’s emollient actions have led to its traditional use for centuries for soothing irritated tissue, coating, and protecting the digestive tract.13 Its high calcium content may have some antacid effects. The herb may be taken as a tea; however, it has a thick, mucus-like consistency that can be unpleasant to women with NVP. To avoid this, one to two teaspoons of slippery elm can be added to oatmeal instead; it is has a pleasant, slight maple syrup–like flavor and is easy to take this way. The easiest and most effective way to use the herb is in the form of slippery elm lozenges, which may be purchased in a conveniently prepared form (e.g., Thayer Slippery Elm Lozenges), are quite palatable, and may sucked on as needed up to 8 to 12 per day. Supporting evidence for the herb’s benefits is drawn from traditional use, and extrapolation from effects of the mucilaginous constituent of the herb. There is no known toxicity, and in fact slippery elm has been used in some baby foods and adult nutritional foods.13

IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA

Iron is essential to multiple metabolic processes, including oxygen transport (e.g., critical to muscle and brain functioning), DNA synthesis, and electron transport. Iron balance in the body is carefully regulated to guarantee that sufficient iron is absorbed in order to compensate for body losses of iron. Either inadequate intake of absorbable dietary iron or excessive loss of iron from the body can cause iron deficiency. Menstrual losses are highly variable, ranging from 10 to 250 mL (4 to 100 mg of iron) per menses. Women require twice the iron intake of men to maintain normal stores, and can expect to lose approximately 500 mg of iron with each pregnancy without careful attention to adequate dietary intake and supplementation.14 Iron deficiency anemia occurs when all of the body’s iron stores have been entirely depleted. This chapter focuses on the iron needs of the pregnant and lactating woman.

Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide, affecting 20% of the world’s population. It is considered the most common health problem faced by women worldwide, adjusted for all ages and economic groups.15 Poor socioeconomic status does, however, further increase the risk of iron deficiency anemia.16 It is estimated that worldwide, 20% to 50% of all maternal deaths are related to iron deficiency anemia.17

During pregnancy the blood volume expands by about 35% to 50%, with additional iron required to meet the needs of the fetus, placenta, and increased maternal tissue. In the second and third trimesters, iron requirements increase to three times the nonpregnant needs. Women who do not supplement iron during pregnancy are usually unable to maintain adequate iron stores throughout and are at increased risk for developing iron deficiency anemia. Women who have a history of iron deficiency anemia prior to pregnancy, low iron stores at the onset of pregnancy, or those with heavy menstrual blood loss, are at further risk for anemia during pregnancy.14,18 Iron deficiency anemia decreases quality of life to due to symptoms of fatigue, weakness, loss of appetite, and increased susceptibility to infection (see Symptoms), and increases the risk of a number of problems including severe anemia from normal blood loss during labor requiring blood transfusions. Fetal iron stores in the first 6 months of life are dependent upon maternal stores during pregnancy.18 Postpartum anemia is a contributing factor to postpartum depression.18

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of iron deficiency anemia include:

Improving iron status noticeably and rapidly improves most of these symptoms.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Conventional treatment of iron deficiency anemia relies primarily on diet and iron supplements.

Iron Supplements

Oral iron supplements are an inexpensive, generally safe, and simple way to treat iron deficiency. Because iron is best absorbed from the duodenum and proximal jejunum, time released and enteric coated preparations are not very effective, and they are also much more costly. Ascorbic acid increases the absorbability of non-heme iron. Taking 250 mg of vitamin C with iron supplement is therefore advisable. Phytates, oxalates, carbonates, calcium, and tannins, found in foods such as cereals, dietary fiber, tea, coffee, eggs, and milk, interfere with iron absorption; therefore, iron supplements should not be taken with food. Antacids also interfere with iron absorption, and should be given several hours prior to or after taking iron supplements. Antibiotics also interfere with iron absorption. Gastrointestinal (GI) side effects are common (10% to 20% of patients report GI side effects) with conventional iron supplements (see Botanical Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anemia for herbal alternatives). Constipation is a common complaint, as are nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, and diarrhea. Elemental iron in the forms of ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate, or ferrous gluconate may be substituted with ferrous sulfate elixir, a liquid preparation that may cause fewer GI symptoms. Improvement can usually be observed starting approximately 7 days after the onset of iron supplementation. Also, though a less effective therapy, iron supplements may be taken with meals to avoid discomfort. The various forms of iron commonly used therapeutically appear to be equally effective. In severe cases where oral iron is unable to be tolerated, parenteral iron may be given. It is considered optimal to remain on iron supplements for approximately 6 months after iron levels return to normal in order to adequately replenish depleted iron stores. Low-dose iron supplementation (30 mg/day) throughout pregnancy is as effective as higher dose supplementation (e.g., 60 mg day) and less likely to cause side effects.15 If a patient does not respond to iron therapy, the possibility of an underlying disorder or coexisting disease (e.g., GI bleeding, thalassemia, and so forth.) must be addressed. Malabsorption is also a common problem leading to refractory anemia.

BOTANICAL TREATMENT

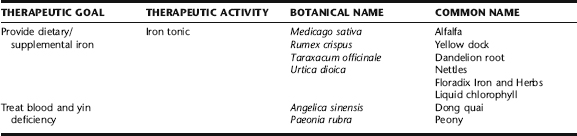

The use of various forms of elemental iron have been a part of both folk and Western medical herbal tradition for at least the past few hundred years, whether in the form of iron nails stuck in apples to infuse the apples with iron for consumption by pioneer women, or the use of ferrum supplements by the Eclectic physicians. As stated earlier, side effects from iron supplements are common. For pregnant women who may be experiencing GI symptoms due to the pregnancy itself, such as nausea, vomiting, or constipation, regular elemental iron supplements may be intolerable. Although there is almost no evidence in the literature evaluating the efficacy or safety of herbs used as “iron tonics,” their use is popular amongst herbalists, midwives, and pregnant women (Table 14-2). Clinical observation has demonstrated a high level of efficacy and minimal side effects (see Case History) with a limited number of botanical supplements. The herbs in this section are those most commonly used in contemporary midwifery and herbal practice.

Nettles

The leaf of the nettle plant, prepared as a strong infusion, is a popular tonic used by many herbalists for treating iron deficiency anemia, many of whom stand by it as one of their primary anemia treatments. The fresh leaves, which lose their sting when cooked, can also be eaten as an iron-rich green leafy vegetable, if one has access to them. The leaves are also rich in chlorophyll, for which they are commonly a commercial source, and a rich source of vitamin C.22 As with other herbs used for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia, the amount of iron in any given dose has not been quantified; however, pregnant women and midwives report good results with symptoms of anemia, particularly fatigue. It is rarely used as a singular treatment but rather as part of a protocol for anemia. It has been suggested, although not demonstrated, that the astringency of this herb might interfere with iron absorption. A 1975 review article by Farnsworth et al. reported that stinging nettle was a potential abortifacient, and that its constituent 5-hydroxytryptamine was a uterine stimulant; however, frequent use of large doses of this herbal infusion in midwifery practice has demonstrated no evidence of such activity.23

Yellow Dock and Dandelion Root Iron Tonic

The use of yellow dock root, in combination with dandelion root, is perhaps one of the most popular Western herb tonics used by midwives.19,20 It is typically prepared as a syrup with blackstrap molasses (see recipe), itself rich

Dandelion-Yellow Dock Syrup for Iron Deficiency Anemia

in iron (and calcium), to be taken daily, usually in a 1- to 2-tbl dose. In this form it is easily digestible, though some women report mild nausea if taken on an empty stomach. Yellow dock is listed in Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases (http://www.ars-grin.gov/duke/) as an iron-containing herb; however, the amount of iron per any single dose of this herb is difficult to quantify and has not been evaluated in regard to its use as an iron supplement. The herb is touted by traditional herbalists, as is dandelion, not only for its iron content but also for its actions on the liver. It is believed to increase uptake of dietary iron. Neither the veracity of this claim nor possible mechanisms have been evaluated. The use of yellow dock as an iron tonic is presented in the 1918 edition of Remington’s Dispensatory of the United States of America: The roots of this plant are said to possess the power to take up the iron present in the soil, and fix it in the form of organic compounds of iron. By watering the plants with a solution of iron carbonate, roots are said to be obtained that contain 1.5% of iron. Rumex is said to give good results in the treatment of chlorosis and anemia. The authors gave the dried and powdered root during meals in doses of 15 to 45 grains (1 to 3 g), in view of their good results they regard it as a valuable iron medicine. Dock root is given in powder or in decoction.21 Note that yellow dock is sometimes considered contraindicated in pregnancy because it is a mild anthraquinone laxative; however, clinically it has not been observed to be associated with increased uterine activity. The gentle laxative effects (aperient) relieve anemia-associated constipation while building iron.

Alfalfa

In 1915, Dr. Richard Willstatter, a German chemist, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for elucidating the structure of chlorophyll. Willstatter observed that the chlorophyll molecule bears a striking resemblance to hemoglobin, except that its centerpiece is a single atom of magnesium rather than iron. Today, commercial liquid chlorophyll is derived mostly from alfalfa, and is popularly used to improve iron levels in iron deficiency anemia. No data evaluating the efficacy or safety of chlorophyll use during pregnancy have been identified. In fact, little data exists on the safety or efficacy of alfalfa, though some preliminary studies have suggested possible beneficial effects in lowering cholesterol.13 The herb may also have some hypoglycemic and antifungal effects.13 Alfalfa is considered to have minimal risk when used as a food source (e.g., a normal serving of alfalfa sprouts) during pregnancy and lactation.22 Animal studies (nonpregnant and lactating) have demonstrated no toxicity when alfalfa seeds or saponins are ingested in large quantities over an extended period of time (up to 6 weeks consumption of seeds and 8 weeks for saponins).13 However, the herb, particularly the seeds and seed products (e.g., alfalfa sprouts) are contraindicated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), in whom it has been reported to cause exacerbations and pancytopenia.13 The constituent thought to be responsible for this effect, l-canavanine, is not present in the leaf; however, lupus-like syndrome has been reported with consumption of leaf-containing tablets. This may be caused by adulteration of leaf products with l-canavanine–containing plant parts. Alfalfa contains the phytoestrogen coumestrol, which may have estrogenic properties. A 1975 paper by Farnsworth et al. on the antifertility effects of herbs stated that alfalfa has uterine stimulant activity; however, no other such findings have been reported in the literature or observed by clinical herbalists.23 Alfalfa is rich in vitamin K, and thus is contraindicated with anticoagulant therapies (e.g., Warfarin) with which it may interfere. It may also interact with hypoglycemic drugs, lower blood glucose levels, interfere with lipid-lowering medications, and should not be taken with Thorazine. Clinically, liquid chlorophyll, combined with other iron-raising protocols, has been observed to rapidly improve hemoglobin more quickly than the protocol used alone, and without adverse effects (see Case History that follows).

Dong Quai and Peony

Blood deficiency, a traditional Chinese medicine diagnosis, akin to iron deficiency anemia, is characterized by fatigue, depression, dizziness, constipation with dry stools, and pale complexion. The traditional Chinese medical literature is replete with treatments for blood deficiency in pregnancy, prescriptions historically tailored to the unique needs of the individual woman. Herbs classically used to treat blood deficiency include dong quai and peony, the two primary ingredients in the classic dong quai and peony formula; however, the literature is scant in demonstrating hematopoeisis or improvements in iron status with its use. There is only a single case report in the literature of a hemodialysis patient who was anemic because of insufficient production of erythropoietin, who self-medicated with dong quai and peony decoction once weekly. The tea was prepared using approximately 12 g of dong quai and 52 g of shao yao decocted in three cups of water reduced to one cup by cooking. The patient was concurrently given recombinant human erythropoietin but appeared to be resistant to it. One month after starting the herbal tea, the hematocrit increased from 29.7% to 34.4%.24 Because of possible hormonal effects and anticoagulant/antiplatelet activity, the herb is listed in several Western sources as contraindicated in pregnancy.13,23,26 Data regarding the effect of dong quai preparations on the fetus are lacking.24 It is recommended that this herb be used in pregnancy only under qualified supervision, and in traditional herbal preparations used for pregnancy.24

After 1 week, Celeste was still constipated, so she was instructed to add the following to her plan:

Three weeks after the initial visit (31 weeks pregnant), Celeste’s hematocrit had risen to 30, and she was having regular bowel movements—one soft, formed stool per day or every other day. It was recommended that she continue taking the preparations for constipation each morning for a couple of additional weeks. It was also recommended that she add 1 tbl liquid chlorophyll to her protocol daily, and take 250 mg vitamin C with each dose of Floradix. It was felt somewhat urgent to quickly raise her hematocrit, as her due date was only 9 weeks away.

PRETERM LABOR AND UTERINE IRRITABILITY

Preterm labor occurs prior to the end of the 37th pregnancy week. Preterm birth is one of the leading causes of infant mortality and also long-term disability in the United States. 27 28 29 In spite of improvements in the outcome of prematurely born infants, the rate of premature delivery has continued to rise, largely as a result of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) and multiple pregnancies, although poor nutrition and lower socioeconomic status continue to play a major role. In 2004, 12.5% of all births in the United States occurred prior to 32 weeks gestation. Rates of preterm birth are highest among African-American women, adolescents, women older than 40, unmarried women, and women with lower socioeconomic status. Additional factors that contribute to premature labor include prior preterm birth, history of second trimester pregnancy loss, preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM), multiple gestation, concurrent obstetric or medical complications, uteroplacental insufficiency, cigarette smoking, drug use, alcohol intake, lack of prenatal care, uterine abnormalities, infections, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), and fetal congenital abnormalities.29,30 Stress, dehydration, domestic violence, emotional abuse, closely spaced pregnancies, and jobs that require a long period of standing are also thought to be contributory to premature labor.30,31 The following specific conditions are associated with premature labor: urinary tract infections, vaginal infections, sexually transmitted infections and possibly other infections, diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, and clotting disorders (thrombophilia).31 Dietary patterns also play a role. Decreased frequency of eating is associated with an increased risk of premature labor. Women who consume three meals and two snacks daily throughout pregnancy appear less likely to experience premature onset of labor.32 Low or no fish consumption, associated with inadequate intake of omega-3 fatty acids, is also associated with an increased risk of premature labor.33 Other nutritional deficiencies, notably vitamin C, may also be related to increased risk of premature labor.34

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Unfortunately, diagnosis of early preterm labor is difficult and has a high false-positive rate, which may lead to possibly harmful interventions for thousands of women. Screening methods for preterm labor such as routine cervical assessment, transvaginal ultrasonography, fetal fibronectin (fFN) detection, and home uterine activity monitoring have not been shown to be beneficial at actually preventing preterm labor, although some of these methods may detect risk or early symptoms, and fFN testing can provide information on the likelihood of a woman entering labor in the two weeks after the test.29

Medical evaluation for the presence of premature labor includes assessment for the following signs:

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Strategies to prevent preterm delivery have focused on early diagnosis of preterm labor symptoms and on clinical markers such as cervical change, uterine contractions, vaginal bleeding, and changes in fetal behavior. Bed rest and home uterine monitoring have not led to a reduction in preterm birth rates. Since, bed rest can lead to potential adverse effects on women and their families, clinicians should not routinely advise women to rest in bed to prevent preterm birth.35 The medical priority is to halt the progression to premature birth whenever possible, while treating underlying medical contributing causes, and assure fetal lung maturity and the availability of proper neonatal care if preterm birth becomes inevitable. Medical treatments used to arrest premature labor include the use of tocolytic agents (e.g., terbutaline, magnesium sulfate, ritodrine, and nifedipine); corticosteroid therapy to stimulate fetal lung maturity, and treatment of underlying causes of premature labor, for example, antibiotics for specific infections. Complications of the use of these medications vary according to the drug, and include but are not limited to pulmonary edema, profound hypotension, muscular paralysis, cardiac arrest, respiratory depression, hypokalemia, hyperglycemia, arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, and maternal death. A risk–harm evaluation is done based on the week’s gestation of the pregnancy, status of the fetus, and reason for premature labor when determining whether to arrest labor medically or to allow labor to proceed. If premature labor is diagnosed and is progressing, the pregnant woman is transferred to a care facility equipped to care for the premature newborn.