Chapter 48 PREGNANCY AND LIVER DISEASE

ABNORMAL LIVER FUNCTION TESTS IN PREGNANCY

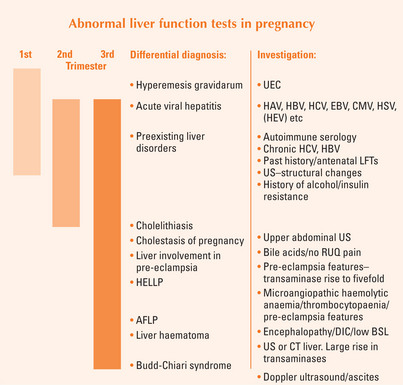

Determine the stage of pregnancy, and whether there is anything in the history to indicate a liver disorder. A pregnancy-related liver disorder should be considered in the event of any relevant past history, or history of medications or in the presence of features of pre-eclampsia.

NORMAL PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES IN PREGNANCY

Normal physiological changes in pregnancy are shown in Table 48.1. The mother’s blood volume increases by 40%, and her total body water increases by 20%. This is reflected in a 10%–60% fall in serum albumin and also a fall in haemoglobin. Up to 50% of women develop spider naevi and palmar erythema during pregnancy, which is thought to be due to the increasing levels of oestrogen. This reverses quickly post delivery. Serum alkaline phosphatase increases 2–4-fold in the third trimester (placental) and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase decreases slightly. No change is observed in the aminotransferases (alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase) or the prothrombin time. A rise in the transaminases should lead to further investigation.

TABLE 48.1 Normal changes in liver function tests during pregnancy

| Blood test | Change during pregnancy |

|---|---|

| Alkaline phosphatase | Increases 2–4-fold (placenta) |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase | No change or slightly decreases |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | No change |

| Alanine aminotransferase | No change |

| Bilirubin | No change or slightly increases |

| Bile salts | No change |

| Albumin | Decreases by 10%–60% |

| Globulin | Increases |

| Caeruloplasmin | Increases |

| Prothrombin time | No change |

| Cholesterol | 2-fold increase |

| Triglycerides | 2–3-fold increase |

Up to 3% of pregnancies are complicated by abnormal LFTs at term. The best guide in determining the cause of abnormal LFTs is the timing of the problem during pregnancy (Figure 48.1). The differential diagnoses include:

Pregnancy is associated with an increased rate of gallstone formation. Hence cholecystitis and cholelithiasis need to be excluded in any pregnant woman presenting with right upper quadrant pain, nausea and abnormal LFTs. The differential diagnosis of right upper quadrant pain (Table 48.5) in late pregnancy includes pregnancy-related liver problems, such as liver involvement in pre-eclampsia, even hepatic infarction or rupture. It should be remembered that the gravid uterus pushes up the appendix, and appendicitis in late pregnancy can present with right upper quadrant pain.

TABLE 48.5 Differential diagnosis for right upper quadrant pain in the third trimester of pregnancy

| Diagnosis | Incidence during pregnancy |

| Pyelonephritis | 1%–2% |

| Cholelithiasis/cholecystitis | 3%–5% have biliary sludge |

| Acute appendicitis | 1/1500 |

| Pancreatitis | 1/1439 |

| AFLP | 1/10,000–1/15,000 |

| Pre-eclampsia + liver involvement | <1% |

| HELLP syndrome | 0.1% |

| Hepatic haematoma/rupture | 1/45,000 |

| Acute viral hepatitis | Same as in the general population |

| Acute Budd-Chiari syndrome | Rare |

AFLP = Acute fatty liver of pregnancy; HELLP = haemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelet syndrome.

LIVER DISEASES UNIQUE TO PREGNANCY

Cholestasis of pregnancy

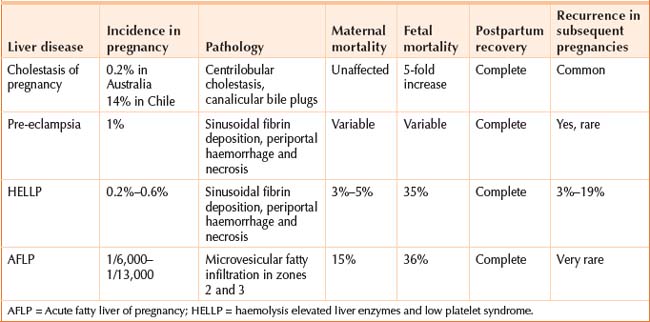

Cholestasis of pregnancy is the most common liver disease unique to pregnancy. The incidence is about 1/500 pregnancies (0.2%) in Australia. A higher prevalence is seen in Scandinavia and South America (14% risk in Chile). The condition is characterised by pruritus, and an increase in the serum bile acid, and is usually seen in the third trimester. Women present with an itch, without any skin lesions (apart from scratch marks). There may be a history of mothers or sisters with the same problem, and it may have occurred in previous pregnancies. The itch normally goes within days after delivery.

Risks to the baby

There is a five-fold increase in the risk of preterm labour and stillbirth. Fetal monitoring does not predict the babies at risk, as there is no problem with placental blood flow. The fetal risk is not understood; high bile acids appear toxic to the baby, and cause myometrial irritability. When the total bile acids are 40 μmol/L or greater, fetal complications can occur. Women with this condition will usually have an induced delivery at 38 weeks, to decrease the fetal risk.

Pre-eclampsia and the HELLP syndrome

The haemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelet (HELLP) syndrome occurs in 0.2%–0.6% of all pregnancies, and in about 20% of women with severe pre-eclampsia. One-fifth of cases occur postpartum. Usually women present after week 32 with anorexia, nausea, right upper quadrant pain and/or bleeding from gums and intravenous access sites. The platelet count is 100,000 × 109/L or less. The blood film is consistent with microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia. Aminotransferases are elevated (>70U/L), lactate dehydrogenase >600 U/L and bilirubin slightly raised. The prothrombin time may be normal unless complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The symptoms can be non-specific, and the condition may not be diagnosed until blood tests are done for pre-eclampsia. Characteristically, these women have rapid weight gain. If the diagnosis is suspected and the LFTs are unremarkable, they should be repeated in 4–6 hours, as things can change quickly.

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) occurs between 1/6659 and 1/113,000 pregnancies, typically in late pregnancy. Symptoms include malaise, vomiting and abdominal pain. Jaundice and signs of hepatic encephalopathy may be evident. Coagulopathy, moderately elevated aminotransferases (500 U/L or below) and renal dysfunction are common. The uric acid is increased. Severe hepatic dysfunction is manifest by profound hypoglycaemia and high ammonia levels. DIC is almost universal, and the condition may progress to fulminant liver failure with death of the mother and the baby.

Fatty acid oxidation enzyme deficiency and severe maternal liver disease

Mothers heterozygous for LCHAD do not have abnormal fatty acid metabolism. However, when the mother carries a fetus that cannot metabolise long chain fatty acids, these accumulate in the placenta, and spill over into the maternal circulation. Triglycerides (fatty acids) accumulate in the mother’s hepatocyte mitochondria, leading to impaired function.

LIVER DISEASES OCCURRING CONCOMITANTLY DURING PREGNANCY

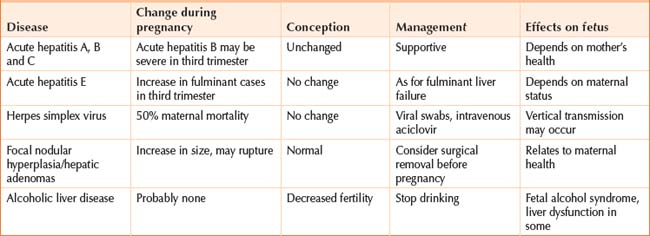

Acute viral hepatitis

Acute viral hepatitis can occur any time during pregnancy. Most cases are due to hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection, but occasionally hepatitis B or C viruses will be the cause. Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus (CMV) can cause a mild hepatitis (but are associated with congenital defects). Rarely, hepatitis is seen with herpes simplex virus (HSV) and herpes zoster virus infections. Herpes simplex hepatitis can be severe in pregnancy; a rash will be seen and treatment with intravenous aciclovir is recommended. A history of intravenous drug use, recent travel or illnesses in other family members supports a diagnosis of viral hepatitis. Skin lesions (such as herpes) and stigmata of chronic liver disease may be apparent on examination. Depending on the clinical situation, the following tests might be ordered: HAV IgM, HbsAb (hepatitis B surface antigen), HCVAb (hepatitis C antibodies) as well as EBV IgM and CMV IgM, and perhaps HSV IgM.

Alcohol problems

A subset of this group will have more advanced liver disease or cirrhosis (see next section).

Cholelithiasis/cholecystitis and pancreatitis

The bile becomes more lithogenic during pregnancy, with gallstones being present in 12% of pregnancies. The risk of biliary and pancreatic problems increases during pregnancy and immediately postpartum. Cholelithiasis/cholecystitis and pancreatitis need to be excluded in any pregnant woman presenting with right upper quadrant or epigastric pain and/or abnormal liver function tests. Check the liver function tests, serum amylase and lipase, and perform an ultrasound. If imaging is required, nuclear magnetic resonance would be the next choice.

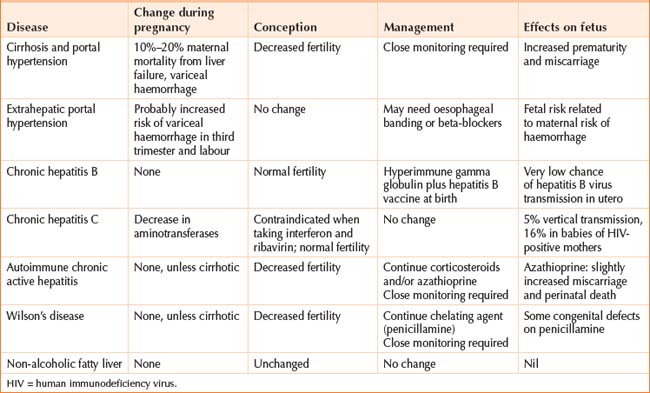

Cirrhosis

Pregnant women with cirrhosis have an increased risk of hepatic decompensation and preterm delivery, and need to be closely monitored during pregnancy. If the mother has portal hypertension, a gastroscopy is recommended to screen for oesophageal varices. If there are oesophageal varices, prophylactic banding and/or non-selective beta-blockers may be recommended, depending on their size and risk of haemorrhage. However, there are reported cases of beta-blockers affecting the growth of the long bones. Women with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension have a normal fertility, but risk a complicated pregnancy, and should be counselled, preferably before conception.

Chronic hepatitis C virus

The LFTs and HCV RNA status should be checked in women who are positive for HCV antibody (that is, anti-HCV positive). There is a 5% risk of vertical transmission in women who are HCV RNA positive. This rate is possibly influenced by the mode of delivery, but as yet there are no recommendations for preferred mode of delivery. Breastfeeding, however, appears to be safe. The risk of vertical transmission relates to maternal viral load, and increases three-fold if the mother is coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This high rate decreases wth antiretroviral drug therapy.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are the most common causes of LFT abnormalities in the general community. As obesity rates rise, so does the incidence of associated liver problems. Liver histology in NAFLD and NASH shows macrovesicular fat, with or without an inflammatory reaction and increased fibrosis. These histological changes are similar to the histology seen with alcohol damage. Whereas the histological features with acute fatty liver of pregnancy are distinct (microvesicular steatosis), NAFLD and NASH remain stable throughout pregnancy and postpartum. The aminotransferases and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase are minimally elevated. An ultrasound may show a hyperechoic liver consistent with fatty infiltration in the liver. Cirrhosis is unlikely to be seen in this age group. Affected women may give a family history of maturity onset diabetes, and have a higher body mass index. They are more likely to be older and have an increased risk of hypertension, diabetes and cholelithiasis.

Benjaminov FS, Heathcote J. Liver disease in pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2479-2488.

Doshi S, Zucker SD. Liver emergencies during pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2003;32:1213-1227.

Glantz A, Marschall HU, Mattsson LA. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology. 2004;40:467-474.

Guntupalli SR, Steingrub J. Hepatic disease and pregnancy: an overview of diagnosis and management. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:S332-S339.

Kaaja RJ, Greer IA. Manifestations of chronic disease during pregnancy. JAMA. 2005;294:2751-2757.

Tham TC, Vandervoort J, Wong RC, et al. Safety of ERCP during pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:308-311.