chapter 54 Pregnancy and antenatal care

PRECONCEPTION COUNSELLING

Chronic medical conditions such as diabetes need to be fully assessed and management optimised.

An important principle to remember is that any investment in the mother’s wellbeing—and the wider family, for that matter—is an investment in the wellbeing of the pregnancy and the future of the child. Preparation for pregnancy needs to address the woman’s physical, emotional and spiritual situation, including her beliefs about her relationship, parenting and lifestyle. It is helpful to consider the elements using the ESSENCE model, as discussed below (also see Ch 6).

EDUCATION

Planning a pregnancy is the time when women are arguably the most interested they have ever been in optimising their health, in the interests of having a healthy baby. It is also an opportunity to discuss the potential father’s lifestyle and general health. The advice provided at the preconception consultation may be the last chance to see the patient before she becomes pregnant, so this consultation needs to address issues that will be important in the early stages of pregnancy, even before she knows she is pregnant.

STRESS MANAGEMENT

Because the mother’s stress hormones (including cortisol and catechols) cross the placenta, maternal stress also affects fetal neurological, physiological and metabolic development. For example, significant and prolonged maternal stress,1,2 particularly in the first trimester, is associated with poorer fetal growth, developmental problems, an increased risk of mental illness and a higher risk of cardiovascular disease in the offspring.

SPIRITUALITY

Starting a family affects a woman, her family and her work in profound ways. Asking about what all this means for her and how she will adjust may be an important conversation. A preliminary discussion of a patient’s religious or spiritual beliefs may be appropriate, particularly if there is a problem with fertility, if the pregnancy fails to proceed or if antenatal testing reveals a fetal abnormality.3 A discussion of the parents’ religious views about circumcision, should they have a male child, may be appropriate in the planning stages.

EXERCISE

Once the patient is pregnant, she can continue or adjust her current exercise program (Box 54.1).

BOX 54.1 Exercise advice for women with a normal pregnancy

NUTRITION

However, women who are either significantly overweight or underweight need to address this risk factor. Obese women are 2.7 times more likely to be infertile than women in the healthy weight range. Obesity in women can also increase the risk of miscarriage and impair the outcomes of assisted reproductive technologies and pregnancy.4 It is also associated with an increased rate of caesarean section.5

Being underweight is associated with reduced conception rates among nulliparous women and increased likelihood of conception among parous women.6

Some foods are to be avoided because of the risk of listeriosis, which causes a risk of miscarriage. These foods include raw seafood, pre-prepared (salad bar) salads, delicatessen meats, leftovers, soft cheeses and pâté. All fruit and vegetables should be washed in filtered water before eating.

ANTENATAL CARE

Women suitable for shared antenatal care with their general practitioner (GP) include those defined as healthy women having a normal pregnancy. Complications usually requiring additional care by an obstetrician or other specialist are summarised in Box 54.2. Some of these women may still be suitable for shared care, with some modification of the usual schedule of visits.

SCHEDULE OF VISITS

The traditional schedule of antenatal visits was developed in the United Kingdom in the 1920s and consists of 14 visits based on first presentation early in pregnancy, monthly visits until 28 weeks’ gestation, fortnightly visits until 36 weeks’ gestation and weekly visits thereafter until delivery. Observational studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of regular antenatal care on perinatal outcomes. Despite varying schedules, the overall aims of antenatal care can be summarised as described below.

Two reviews of the literature8,9 have suggested that reducing this schedule of visits to 10 is equally effective in achieving positive perinatal outcomes in low-risk gravidas, although it may be associated with a decrease in satisfaction with care. In particular, there was no difference in perinatal outcomes between primigravidas and multigravidas.

MODELS OF CARE

Routine involvement of specialist obstetricians in low-risk maternity care is not associated with any improvement in perinatal outcomes compared to involving obstetricians when complications arise.9 Midwifery and GP-led models of care are safe for low-risk women. Women are more likely to be satisfied with their care where there is continuity of care, or carer. At each antenatal visit, midwives and doctors should offer information, consistent advice and clear explanations and provide the opportunity to ask questions.

INITIAL RECOMMENDED TESTS

OTHER TESTS TO BE CONSIDERED

Other recommended tests

26 weeks

36 weeks

PRENATAL SCREENING FOR ANEUPLOIDY

The first-trimester combined screen consists of nuchal translucency in combination with maternal age and serum markers, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) and the free beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotrophin (fβhCG). Trisomy 21 detection rates are estimated at about 87% for a false-positive rate of 5%.15,16 This rate depends on the timing of the individual components. The test is most informative when the serum markers are performed during the ninth week of gestation and the nuchal translucency component during the twelfth week. The advantages of the first-trimester test include higher detection rates, more straightforward termination procedures for those choosing to terminate an aneuploid pregnancy, and earlier reassurance.16

Nuchal translucency can be used alone. This approach is often taken for multiple gestations.

A number of ‘soft’ markers have been described which increase the risk of aneuploidy when present. These include nasal bone hypoplasia, cystic hygroma, abnormal ductus venosus flow and tricuspid regurgitation at the first-trimester ultrasound. Markers identified at the routine second-trimester morphology scan include nuchal translucency, short femur or humerus, pyelectasis, echogenic bowel, echogenic intracardiac focus, single vessel cord and any major structural malformation. Definitive testing is usually offered to women with two or more of these markers, which in studies were observed in 15.1% of cases and 1.6% of normal controls.17

THE STANDARD ANTENATAL CHECK

Smoking

Evidence indicates serious fetal risks associated with maternal smoking. Meta-analysis has demonstrated twice the normal risk of low birth weight for babies of mothers who smoke (RR 2.04). Preterm birth is a third more likely (RR 1.34) and IUGR risk is more than doubled (RR 2.28). The risk of sudden infant death syndrome is almost three times higher (RR 2.76), and maternal smoking is associated with 10% of stillbirths (RR 1.33) and spontaneous abortions (RR 1.36).18,19

Blood pressure measurement

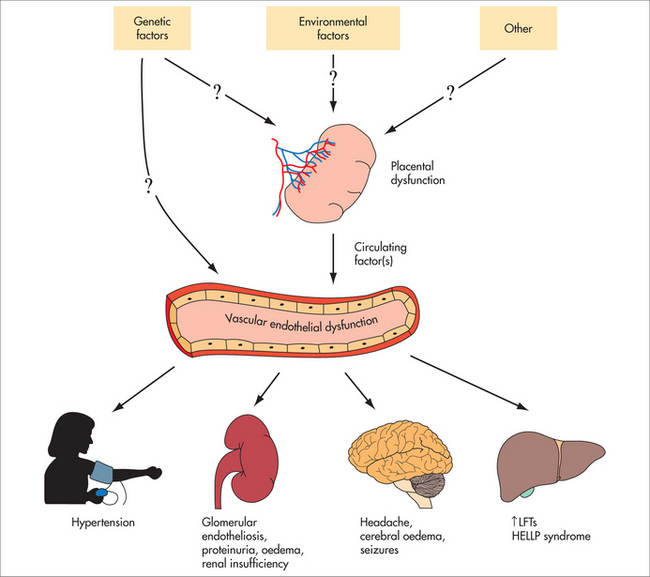

Hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg. Previous definitions included an incremental rise of 30 mmHg systolic or 15 mmHg diastolic compared to blood pressure as measured in the first trimester; however, most recent definitions have excluded the incremental rise in favour of the former definition. Automated devices should not be used and the role of ambulatory monitoring is currently uncertain. Elevated blood pressure is one of the early signs of preeclampsia, a major cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity (see Fig 54.1). Early detection is important, as the condition can progress rapidly. Hypertension in pregnancy without preeclampsia is also associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. A diagnosis of hypertension in pregnancy requires early assessment by a specialist obstetrician. A clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia is usually made when hypertension occurs with one or more of proteinuria, renal insufficiency, biochemical liver abnormalities, neurological signs, haematological disturbances or fetal growth restriction, and again it requires early assessment by a specialist obstetrician.

Blood pressure greater than 170/110 mmHg requires immediate admission to hospital.

Measurement of the symphyseal–fundal height

Intrauterine growth follows a standard curve pattern. The maximum rate of growth occurs between 20 and 32 weeks and is generally 1 cm per week. After 32 weeks’ gestation, the rate of growth decreases slightly. Any variation in measurement from the expected may lead to a diagnosis of small for gestational age (SGA) or large for gestational age (LGA). These are somewhat vague terms that relate to the 10th and 90th centiles respectively and may or may not represent pathology. A baby who is SGA may be well and constitutionally small or may have IUGR. The diagnosis of IUGR is very important as these fetuses are at high risk of fetal death in utero, especially in postdates pregnancies. Other risks for these fetuses include perinatal morbidity, neurodevelopmental delay and endocrinological disorders. IUGR is usually further subdivided into symmetrical and asymmetrical, based on measurements of head size compared to body measurements such as abdominal circumference and femur length. Symmetrically small fetuses are more likely to have chromosomal abnormalities or intrauterine infection, as opposed to asymmetric growth restriction, which is more likely to be due to placental insufficiency and reflects the phenomenon of head sparing, by which the fetus attempts to preserve the blood supply to its most important organ, the brain, at the expense of the rest of the body. The diagnosis of IUGR really rests on evidence of slower growth than expected from two scans more than 2 weeks apart, but the diagnosis of placental insufficiency can be inferred at a single examination on the basis of a small baby and the abnormalities of markers of biophysical wellbeing. These include the amniotic fluid index (AFI), Doppler flow studies of the umbilical artery, middle cerebral artery and ductus venosus. Changes in the latter two suggest that the changes in blood flow associated with head sparing are taking place.

Fetal presentation and descent

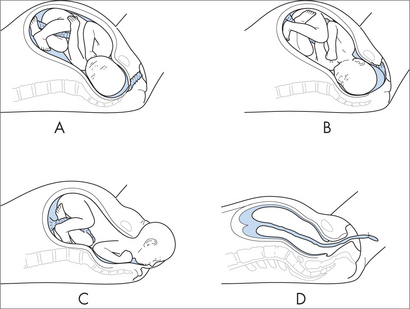

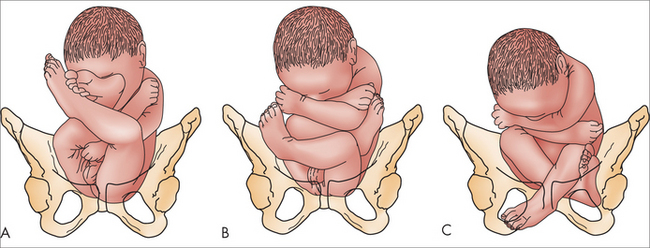

A check to determine the presenting part should be performed as part of fetal palpation from about 30 weeks. Malpresentation is more likely with increasing maternal age, probably secondary to increasing incidence of uterine factors such as fibroids, which may alter the shape of the cavity and thus predispose to breech presentation or the uterine laxity associated with multiparity. The Term Breech Trial demonstrated a decrease in perinatal mortality or serious morbidity in developed countries for delivery by planned caesarean section rather than planned vaginal birth with no increase in serious morbidity or mortality for mothers.20 Following the findings of this trial, practice in general has changed to favour elective caesarean section for all breech presentations at term, both multigravid and primigravid. This has increased the importance of the diagnosis of breech presentation, to allow for appropriate counselling.

3 centres collaboration, guidelines on antenatal care. http://www.3centres.com.au/guide_frame.htm.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand, Advice for women with babies on their minds or in their arms. http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumerinformation/adviceforpregnantwomen/.

Health Insite, Exercise and pregnancy. http://www.healthinsite.gov.au/topics/Exercise_and_Pregnancy.

1 Bergman K, Sarkar P, O’Connor TG, et al. Maternal stress during pregnancy predicts cognitive ability and fearfulness in infancy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1454-1463.

2 Talge NM, Neal C, Glover V. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(3/4):245-261.

3 Mann, Jr, McKeown RE, Bacon J, et al. Predicting depressive symptoms and grief after pregnancy loss. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;29(4):274-279.

4 Pasquali R, Patton L, Gambineri A. Obesity and infertility. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2007;14(6):482-487.

5 Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Gurung T, et al. Obesity as an independent risk factor for elective and emergency caesarean delivery in nulliparous women—systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Obes Rev. 2009;10(1):28-35.

6 Wise LA, Rothman KJ, Mikkelsen EM, et al. An internet-based prospective study of body size and time-to-pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(1):253-264.

7 3 Centres Collaboration. Guidelines on antenatal care (last reviewed 2006). Mercy Hospital for Women, Southern Health and Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne. Online. Available: http://www.3centres.com.au/guide_frame.htm.

8 Khan-Neelofur D, Gülmezoglu M, Villar J. Who should provide routine antenatal care for low-risk women, and how often? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. WHO Antenatal Care Trial Research Group. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1998;12(Suppl 2):7-26.

9 Villar J, Carroli G, Khan-Neelofur D, et al. Patterns of routine antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD000934.

10 Moise KJJr. Non-anti-D antibodies in red-cell alloimmunization. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;92(1):75-81.

11 Giles ML, Mijch AM, Garland SM, et al. HIV and pregnancy in Australia. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44(3):197-204.

12 Pérez-López FR. Vitamin D: the secosteroid hormone and human reproduction. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(1):13-24.

13 Mater Hospital Perinatal Epidemiology Unit and Queensland Council on Obstetric and Paediatric Morbidity and Mortality. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the prevention of neonatal early-onset group B streptococcus disease. MPEU and QCOPMM, Brisbane; 2000 (cited in 3 centres collaboration – see ref 7).

14 Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Institute. Guidelines on prophylactic use of Rh D immunoglobulin (anti-D) in obstetrics. Online. Available: http://www.health.gov.au/nhmrc/publications/pdf/wh27.pdf.

15 Jaques AM, Halliday JL, Francis I, et al. Follow-up and evaluation of the Victorian first-trimester combined screening programme for Down syndrome and trisomy 18. BJOG. 2007;114(7):812-818.

16 Breathnach FM, Malone FD. Screening for aneuploidy in first and second trimesters: is there an optimal paradigm? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19(2):176-182.

17 Bethune M. Literature review and suggested protocol for managing ultrasound soft markers for Down syndrome: thickened nuchal fold, echogenic bowel, shortened femur, shortened humerus, pyelectasis and absent or hypoplastic nasal bone. Australas Radiol. 2007;51(3):218-225.

18 Lumley J, Oliver S, Waters E. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD001055.

19 English D, Holman CDJ, Milne Winter MG, et al. The quantification of drug-caused morbidity and mortality in Australia 1995: Part 2. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health, 1995.

20 Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, et al. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375-1383.