Pregnancy

Haematological changes

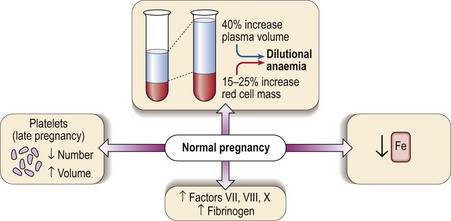

Several haematological changes occur in normal pregnancy (Fig 44.1). Beginning in the sixth week there is an increase in plasma volume accompanied by an increase in red cell mass. The plasma volume expansion peaks at around 24 weeks when it is approximately 40% greater than in a non-pregnant woman. As the increase in red cell mass is more modest (15–25%) a dilutional anaemia is inevitable. In practice the haematocrit and haemoglobin level start to fall at 6–8 weeks and reach a trough at around 20 weeks. It is unusual for the haemoglobin level to fall below 100 g/L and if this happens another cause for anaemia should be sought. Negative iron balance can be regarded as routine in pregnancy and as discussed below frank iron deficiency commonly occurs.

Coagulation abnormalities in pregnancy

Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy

Heparin. Neither unfractionated standard heparin nor low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) cross the placenta. LMWH is widely used and is both safe and effective in the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy, with significant bleeding, usually from primary obstetric causes, in less than 2% of cases. Anti-factor Xa levels can be monitored but the optimal therapeutic range is unclear.

Heparin. Neither unfractionated standard heparin nor low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) cross the placenta. LMWH is widely used and is both safe and effective in the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy, with significant bleeding, usually from primary obstetric causes, in less than 2% of cases. Anti-factor Xa levels can be monitored but the optimal therapeutic range is unclear.

Warfarin. Warfarin is not significantly secreted in breast milk and treatment is safe during lactation. However, it readily crosses the placenta and is a known teratogen, producing a specific warfarin embryopathy at around 6–12 weeks (approximately 5% incidence). Thus, heparin should be substituted for warfarin in the first trimester. There may be a risk of fetal haemorrhage secondary to warfarin throughout pregnancy, particularly if anticoagulant control is poor, and the risk to mother and fetus becomes unacceptable in the antepartum period. It should therefore be discontinued at 36 weeks and heparin substituted until after delivery. Current practice is to avoid use of oral anticoagulants in pregnancy wherever possible. There is currently no place for the newer oral anticoagulants (i.e. direct thrombin and anti-Xa inhibitors) due to concerns regarding toxicity.

Warfarin. Warfarin is not significantly secreted in breast milk and treatment is safe during lactation. However, it readily crosses the placenta and is a known teratogen, producing a specific warfarin embryopathy at around 6–12 weeks (approximately 5% incidence). Thus, heparin should be substituted for warfarin in the first trimester. There may be a risk of fetal haemorrhage secondary to warfarin throughout pregnancy, particularly if anticoagulant control is poor, and the risk to mother and fetus becomes unacceptable in the antepartum period. It should therefore be discontinued at 36 weeks and heparin substituted until after delivery. Current practice is to avoid use of oral anticoagulants in pregnancy wherever possible. There is currently no place for the newer oral anticoagulants (i.e. direct thrombin and anti-Xa inhibitors) due to concerns regarding toxicity.

DIC in pregnancy

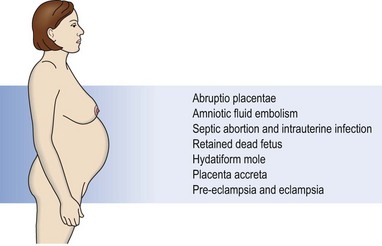

DIC is associated with a wide variety of situations in pregnancy (Fig 44.2). The chief characteristics and pathogenesis of DIC are discussed on page 76. In pregnancy, DIC may manifest as a chronic compensated state or as life-threatening haemorrhage. The latter is a frightening medical emergency and there should be a planned regimen of management with input from an obstetrician, haematologist, physician, anaesthetist and nurse (Table 44.1). It is imperative that the source of bleeding is identified and addressed as soon as possible. It is often shock which triggers DIC with a resultant increase in bleeding.

Table 44.1

General guidelines for the management of acute obstetric haemorrhage

Secure venous access and insert a central line to measure central venous pressure (CVP)

Secure venous access and insert a central line to measure central venous pressure (CVP)

Seek additional (preferably senior) medical help

Seek additional (preferably senior) medical help

Collect samples for urgent blood count, crossmatching and coagulation screen; liaise with haematology laboratory

Collect samples for urgent blood count, crossmatching and coagulation screen; liaise with haematology laboratory

Restore blood volume – may have to use unmatched blood of patient’s ABO and Rh group (preferred to group O Rh negative)

Restore blood volume – may have to use unmatched blood of patient’s ABO and Rh group (preferred to group O Rh negative)