Etiology

An ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy that occurs as a result of implantation of a fertilized ovum outside the endometrial cavity. Ectopic pregnancy occurs in approximately 1.5% to 2.0% of gestations and can be life threatening, accounting for 6% of all maternal deaths because of late presentation or unrecognized symptoms. Ectopic pregnancy is most common in the fallopian tube, especially when damaged by prior tubal surgery, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, or previous ectopic pregnancies.

Less than 10% of ectopic pregnancies occur in the cervix, the cornua, the ovary, or the abdomen. These are more difficult to diagnose and treat, thus resulting in higher morbidity than tubal pregnancies. More recently, implantation in Cesarean section scars has been described with increasing frequency.

Ultrasound Findings

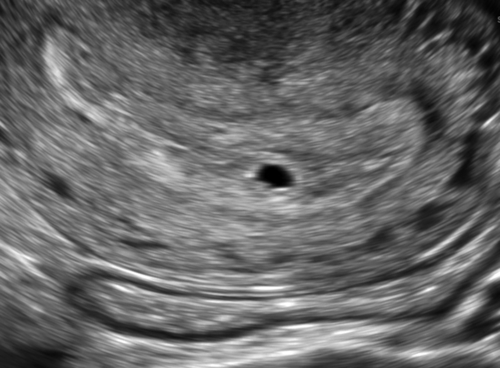

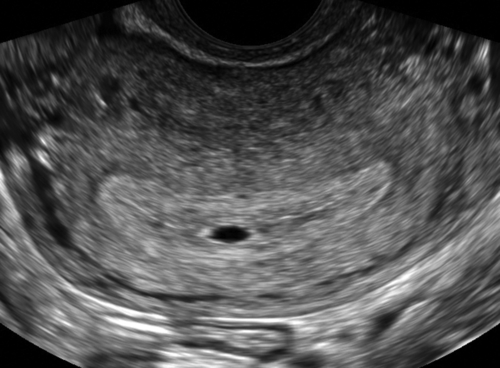

Transvaginal ultrasonography has 73% to 93% sensitivity for diagnosing ectopic pregnancy, depending on sonographer expertise and gestational age. On rare occasions, there is a gestational sac with a live embryo in the adnexa and the sonographic diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy can be definitive. In 8% to 31% of women suspected of having an ectopic pregnancy, the initial ultrasound does not show the whereabouts of the pregnancy (pregnancy of unknown location [PUL]).

An empty-appearing uterus may indicate an intrauterine pregnancy too early to see (less than 5 weeks), a failed pregnancy too small or already passed, or an ectopic pregnancy. Technical factors such as fibroids, adenomyosis, morbid obesity, or an axial uterus may make imaging more difficult. Approximately 7% to 20% of women presenting with a PUL are ultimately diagnosed with ectopic pregnancy.

When there is no visible intrauterine pregnancy, it is important to determine the level of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Serial hCG levels are necessary when evaluating pregnancies of unknown location to observe the trend. In a normal early pregnancy, hCG levels will rise by at least 53%, but typically greater than or equal to 100% (99% confidence interval) every 48 hours. Most ectopic pregnancies are associated with a low and abnormally slow rising hCG level. The reported “discriminatory hCG value” at which an intrauterine pregnancy must be identified sonographically has varied in the literature between 1000 and 3000 mIU/mm. It is probable that a patient with an empty uterus and an hCG level of greater than 3000 mIU/mm has an ectopic pregnancy unless she has had a recent complete spontaneous abortion between the time of the hCG and the sonogram.

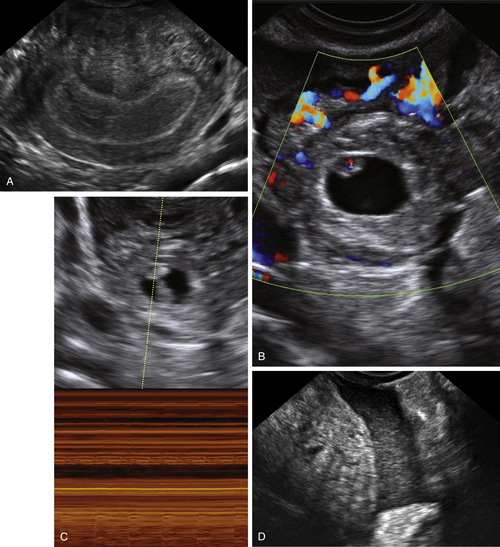

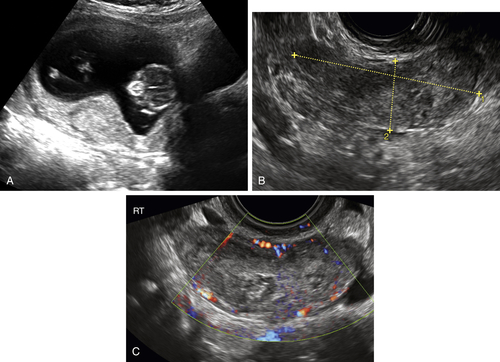

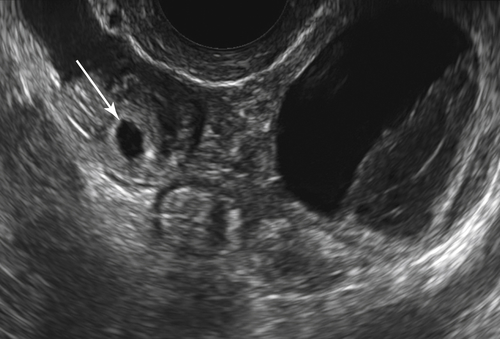

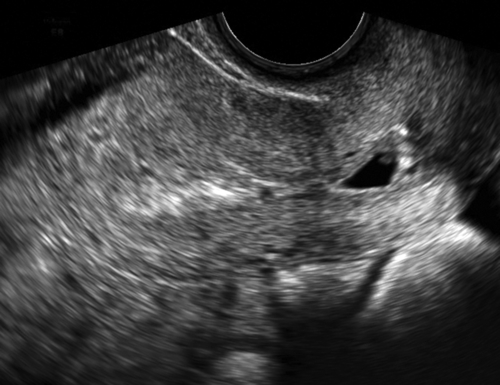

In the absence of an intrauterine pregnancy, the most common sonographic signs of a tubal pregnancy include an adnexal mass (heterogeneous cystic and/or solid), a tubal ring (small round cyst with echogenic rim), a tubular mass consistent with a hematosalpinx, and echogenic free fluid in the cul-de-sac consistent with blood. Color Doppler often shows circumferential flow around a tubal ring, similar to a corpus luteum, but there is typically no flow inside a hematosalpinx. It is helpful to distinguish the ovary as separate from the ectopic pregnancy mass so as not to misdiagnose the mass as ovarian in origin. Pushing the mass gently past the ovary can demonstrate that they are separate.

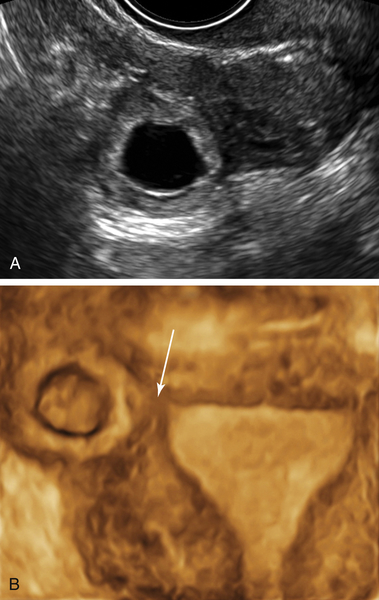

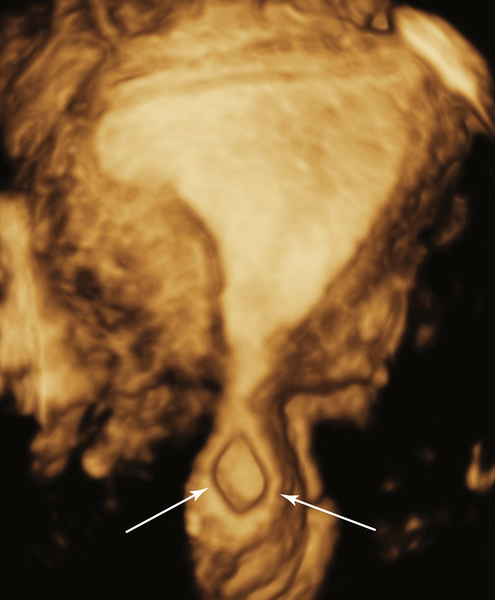

Cornual ectopic pregnancies account for 1% to 6% of ectopic pregnancies and can be diagnosed if the gestational sac is located clearly outside of the endometrial cavity but surrounded by

a thin rim of myometrium. If there is myometrium between the gestational sac and the endometrial cavity, then the pregnancy is cornual.Cervical ectopic pregnancies account for less than 1% of ectopics and are diagnosed when the gestational sac is clearly seen within the cervix. A sac can slide through the cervix during a spontaneous pregnancy loss; therefore if this is suspected, a follow-up scan in 24 hours may be necessary to confirm a cervical pregnancy. Blood flow is typically present around the sac of a pregnancy implanted in the cervix as opposed to an ongoing pregnancy loss in which circumferential blood flow is absent.

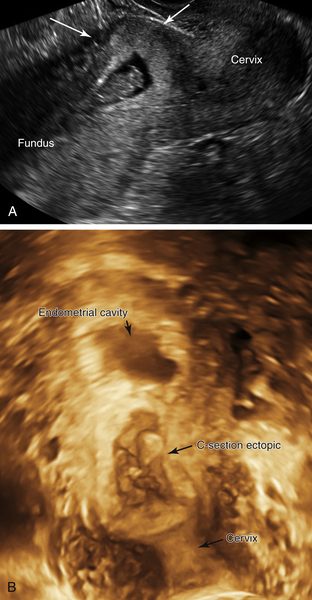

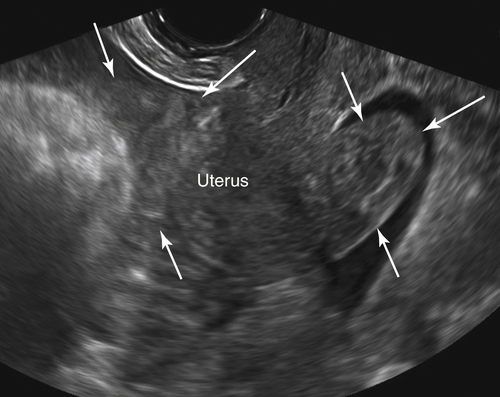

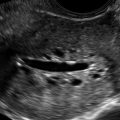

Cesarean section scar pregnancies account for up to 6% of ectopic gestations in women with prior Cesarean sections. The gestational sac is typically located low and anterior, just cephalad to the internal os, obliterating the site of the C-section scar. The sac deforms the anterior lower uterine segment, causing an anterior bulge, with very little myometrium, if any, stretched around the outer surface of the sac, bringing it adjacent to the bladder.

Although the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy is good evidence against the presence of an ectopic pregnancy, the presence of a heterotopic pregnancy (co-existing intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies) is possible, and is more common with the use of assisted reproduction. The sonographic signs of ectopic pregnancy should be sought even if an intrauterine pregnancy is present.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy depends entirely on the presence of a positive pregnancy test, which is an essential finding before a differential diagnosis is attempted.

An ectopic pregnancy can masquerade as a hydrosalpinx, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, appendicitis, ovarian tumor, degenerating pedunculated fibroid, and so on. In the setting of a positive pregnancy test and no visible intrauterine pregnancy, an adnexal lesion should raise suspicion for an ectopic pregnancy. A cervical pregnancy may be confused with an ongoing spontaneous abortion. Doppler is useful to determine whether the sac is attached in the cervix or just passing through. A cornual pregnancy may mimic a degenerating fibroid, but the clinical history and pregnancy test should contribute to the correct diagnosis.