Pregnancy

Maternal physiology

Maternal physiology changes so dramatically during pregnancy that reference intervals for biochemical tests in non-pregnant women are often not applicable. The main differences in commonly requested tests are shown in Table 76.1. These differences should not be misinterpreted as indicating that some pathology is present.

Table 76.1

Reference intervals in the third trimester of pregnancy, and how they compare with non-pregnant controls

| Serum/blood measurement | Pregnant | Non-pregnant |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.2–4.6 | 3.5–5.3 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 97–107 | 95–108 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 18–28 | 22–29 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 1.0–3.8 | 2.5–7.8 |

| Glucose (fasting) (mmol/L) | 3.0–5.0 | 4.0–5.5 |

| Adjusted Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.2–2.8 | 2.2–2.6 |

| Magnesium (mmol/L) | 0.6–0.8 | 0.7–1.0 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 32–42 | 35–50 |

| Bilirubin (µmol/L) | <15 | <21 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 3–28 | 3–55 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 3–31 | 12–48 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 174–400 | 30–130 |

| Blood H+ (nmol/L) | 34–50 | 35–45 |

| Blood PCO2 (kPa) | 3.0–5.0 | 4.4–5.6 |

Weight gain

The products of conception. These include the fetus, placenta and amniotic fluid.

The products of conception. These include the fetus, placenta and amniotic fluid.

Maternal fat stores. These may account for up to 25% of the weight increase.

Maternal fat stores. These may account for up to 25% of the weight increase.

Maternal water retention. Total body water increases by about 5 L, mostly in ECF. The volume of the intravascular compartment increases by more than 1 L.

Maternal water retention. Total body water increases by about 5 L, mostly in ECF. The volume of the intravascular compartment increases by more than 1 L.

Pregnancy-associated pathology

Gestational diabetes

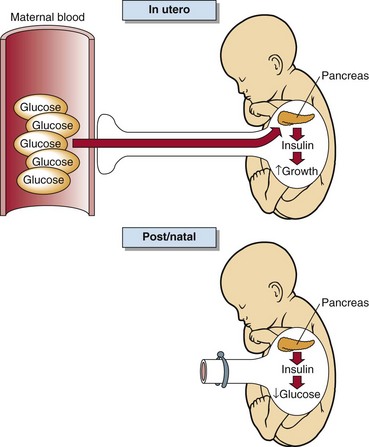

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy. This definition applies irrespective of treatment modality used and whether or not the condition persists after pregnancy. It recognizes the possibility that unrecognized glucose intolerance may have antedated or begun concomitantly with the pregnancy. Depending on the population studies, the prevalence of GDM may be as high as 10% of all pregnancies. Maternal glycaemic status should be rechecked 6 weeks after delivery; women with GDM are at increased risk of developing diabetes, usually type 2, after pregnancy. Maternal hyperglycaemia promotes hyperinsulinism in the fetus (Fig 76.1). Insulin in a growth factor, and babies of poorly controlled diabetic patients are large and bloated. GDM is associated with increased fetal morbidity and mortality. Tight control of diabetes during pregnancy decreases complications.

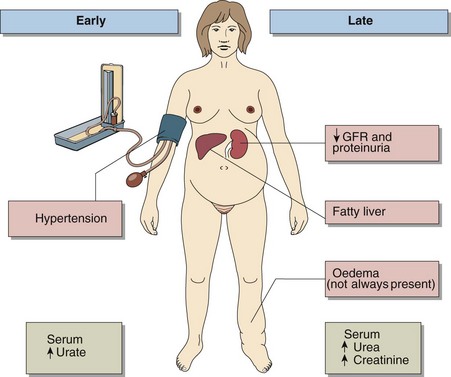

Hypertension

The patient who develops hypertension in pregnancy – a condition described variously as pre-eclampsia or pregnancy-induced hypertension – is at increased risk of placental insufficiency and consequent fetal intrauterine growth retardation. The hypertension is thought to be the causative factor of eclampsia, a severe illness that usually occurs in the second half of pregnancy and is characterized by generalized convulsions, extreme hypertension and impaired renal function including proteinuria. This disease is a significant cause of maternal death, which occurs most commonly as a result of cerebral haemorrhage. The features of pre-eclampsia are shown in Figure 76.2. There are similarities between pre-eclampsia and two other conditions seen in pregnancy – namely the HELLP syndrome (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets) and acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Blood-borne factors from a poorly perfused placenta may activate the maternal endothelium, causing endothelial dysfunction and vascular damage. Altered liver metabolism may also contribute, especially to acute fatty liver of pregnancy, by contributing to triglyceride accumulation in the liver. Frequently it is difficult to decide on the optimum time for delivery. Laboratory investigations may help inform this decision. These include transaminases (AST and ALT), LDH, platelet count, triglyceride and urine protein.