CHAPTER 27 Practical Issues in Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty—The Secrets for Success

Introduction

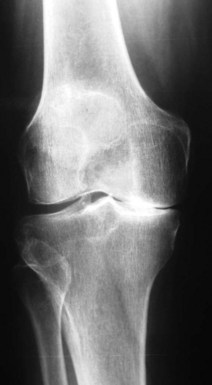

The single most important determinant in a good outcome following a UKA is patient selection (Fig. 27–1). Most authors refer to the traditional selection criteria originally written by Kozinn and Scott.1 These criteria say that UKAs should not be used in patients with more than a 10° fixed flexion contracture or varus or valgus deformity, and they should be used predominantly in thin, elderly, low-demand patients. Flexion deformity is usually considered the most important of these exclusions. More recently, there has been a cautious expansion of the indications to include younger2,3 and heavier4–6 patients. While the data are still relatively short term, there are increasing reports of the successful use of this concept in young (less than 60 years of age) patients at midterm follow-up. If this procedure can provide reasonable outcomes at 10 years, the thinking goes, then this relatively less involved procedure will have served as a “time buyer” until a further conversion to a TKR is performed. There is a growing appeal of thinking of a UKA as a patient’s first arthroplasty for the younger patient and a last arthroplasty for an elderly patient. Another reason for the increased use of UKA in younger patients is that the concept is an appealing one to these patients and, with the increased use of the Internet and direct-to-patient marketing, patients in this age category are increasingly aware of these surgical options and frequently seek out these procedures. Weight has been a concern with UKA procedures but, like use in younger patients, there are reports showing that excess weight, in and of itself, is not a contraindication. These reports are still in the midterm, but the traditional criterion of an 85- to 90-kg limit is being challenged.

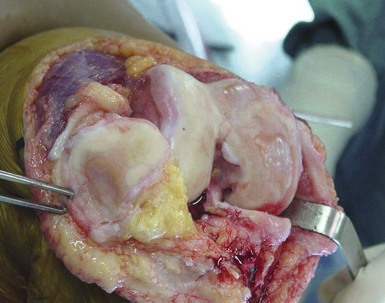

There are several other important aspects to patient selection. These include the status of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the amount of disease present in the other compartments, the presence of crystalline disease and other inflammatory arthropathies, and location of a patient’s pain. Most surgeons feel that a functioning ACL is important, particularly with mobile-bearing devices. The amount of disease in other compartments is controversial. Most surgeons will accept up to Grade 3 Outerbridge damage but not Grade 4, but some surgeons ignore cartilage damage in the patellofemoral joint entirely. The damage often seen on the medial aspect of the lateral femoral compartment due to irritation of the tibial spine is usually ignored (Fig. 27–2). The presence of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals on radiographs or at surgery or the finding of an inflammatory synovium at the time of arthrotomy would be considered by most to be a contraindication to proceeding with a UKA. Some surgeons feel that, for a patient to be a UKA candidate, he or she should be able to point with one finger to the area of pain (medial femoral-tibial joint for medial UKA). Patients with more anterior knee pain or those who complain of pain while going up or down stairs are, in their minds, less ideal candidates for this type of surgery. This idea, however, is also being challenged and now many surgeons are not as concerned with the location of the pain as they are with the preoperative radiographs and examination. Another important factor in patient selection is the patient’s understanding of the concept and the procedure. Patients looking for the most predictable surgical management of their knee disease are probably best served by having a TKR despite the isolated nature of their disease. On the other hand, many patients find the idea of a less invasive procedure, where only the diseased part of the knee is replaced, an appealing one even if it does not have as good long-term follow up as a TKR. It is important that the patient understand the differences and the pros and cons of both approaches.

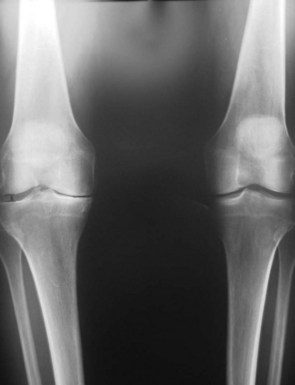

Once appropriate patient selection has occurred, UKA preoperative planning is important. A UKA should be thought of as replacing what has worn away. It should not be used to correct a significant malalignment or deformity. A general sense of the patient’s knee is important. Has the patient always had a varus knee? If so, it is important not to overcorrect the joint line. Using the anteroposterior (AP) radiograph, the surgeon should plan the level of tibial resection to be essentially perpendicular to the long axis of the tibia, although slight undercorrection is acceptable (Fig. 27–3). Because only one part of the joint is being replaced, it is imperative that the lateral radiograph be evaluated so the UKA will reproduce the preexisting posterior tibial slope. Failure to do so will lead to loosening and implant failure. The range of posterior tibial slope has been measured to be anywhere from 0° to 22° (Fig. 27–4).

Technique

At each step of the procedure there are several keys to success.

Appropriate Exposure

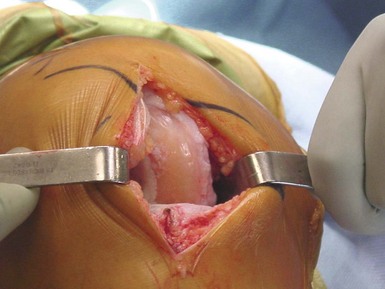

Most UKAs are now performed via a “minimally invasive” approach (Fig. 27–5). In the strictest sense, this does not describe the length of the incision; rather, it means that the extensor mechanism is not displaced from the trochlear groove. With the patella in place, the femoral-tibial alignment and orientation are easier to gauge and evaluate. Incisions should extend approximately from the top of the patella to the joint line. An adequate synovectomy at the arthrotomy enhances visualization and allows for further inspection of the remaining joint, ligaments, and synovium. As opposed to a TKR, where most of the surgery is done either at full extension or at 90° of flexion, a UKA is performed at a variety of flexion positions, and therefore the incision should be large enough to allow an adequate view of the joint. Soft tissues are at risk in these small incisions, so retractor placement is important, particularly along the medial joint line to protect damage to the medial collateral ligament. Extending the length of the incision should always be done if visualization is compromised.

Conservative Tibial Resection

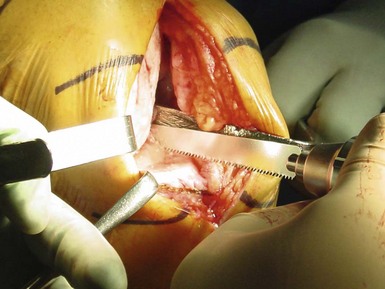

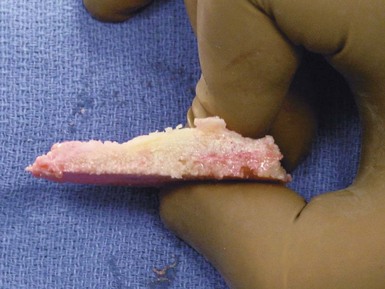

Following the idea that a UKA should be replacing what is worn, based on the preoperative planning radiographs, a minimal amount of tibial bone should be removed—a few millimeters at most off the medial plateau for a medial UKA. Both the vertical and horizontal cuts are important. It can be helpful to use the lateral border of the medial femoral condyle as a cutting guide for the L or vertical cut of the tibial bone resection (Fig. 27–6). Placing the reciprocating saw along the lateral aspect of the medial condylar bone and medial to the ACL is a remarkably consistent landmark for the vertical cut for the tibia. The horizontal cut should be approximately at 90° to the long axis of the tibia and at 90° to the “L” cut. Various cutting guides can be helpful for planning this cut (Fig. 27–7). The amount of posterior slope must match the native knee and should be carefully planned on the preoperative radiographs. In many cases, because the majority of bone loss in UKA knees is anterior, when the knee is flexed there is a normal amount of residual cartilage between the femur and tibia. Placement of a thin guide in this position is an intraoperative check to ensure appropriate slope to the tibial cut. Because this is a tibia-first sequence, this cut is extremely important. Care must be taken to avoid lifting the hand when making the vertical cut as the tibial bone becomes quite soft posteriorly. Because there is almost never any bone or cartilage loss in the notch, inspection of the medial aspect of the removed tibial bone should show that the anterior and posterior parts of the cut surface are the same thickness. This confirms that the appropriate slope has been applied to the tibial cut (Fig. 27–8).

Assessing the Flexion and Extension Gaps

At this point the resected tibial bone can be used to get an approximate size of the tibia to be replaced. Spacers of various thicknesses can be used to assess the flexion and extension gaps (Fig. 27–9). For proper balance in extension, the knee should fully extend and have about 1–2 mm of laxity in full extension. To test the flexion gap, the knee should be flexed and the same spacer should be placed into the flexion gap. Most UKA patients have extension gap loss (anterior tibia and weight-bearing femur cartilage loss) and the posterior femoral cartilage is often of normal thickness. If the knee is too tight in flexion but stable in extension, one option is to use the oscillating saw to resect 1–2 mm of cartilage off the posterior aspect of the femur; this will usually equalize the gaps.

Mating the Distal Femoral Cut to the Tibial Cut

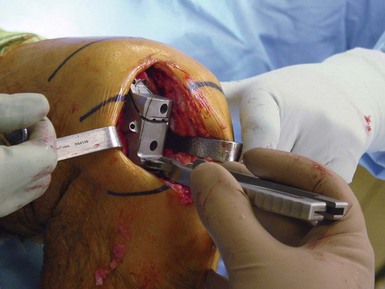

To ensure stability in stance and fixation of implants, the femoral cut should be mated to the tibial cut in extension. As was previously mentioned, the tibial cut can be placed in anywhere from 0° to 22° of posterior slope. This slope is usually approximately 5° but it needs to be considered in the planning of the femoral cut. This cut can be planned with either intra- or extramedullary guides. Use of a cutting guide that sits on the cut tibial surface ensures that the distal femur cut matches the tibial cut. If the tibial cut has been made in posterior flexion (as is usually the case), the knee should be held in slight flexion while the guide is pinned to the femur. This will make the femoral cut in slight extension and this will help mate the femoral and tibial cuts (Fig. 27–10). It is important that enough bone has been resected off the distal femur so that the femoral implant will sit on a large enough bed that is not overly sclerotic, this will allow the cement to interdigitate with the bone and allow more durable fixation of the femoral component.

Sizing and Orienting the Femoral Trial

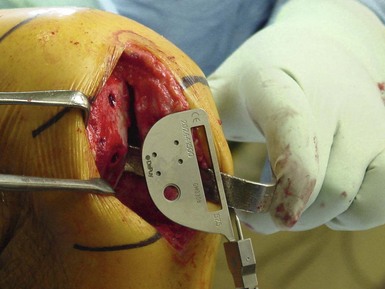

There is great variability in the shape and size of the distal femoral condyles. The femoral sizing in most modern UKA systems is independent of the tibial size. In many cases the so-called tidemark (Fig. 27–11) where the cartilage loss ends on the distal femur is a good landmark for placement of the femoral trial. In general, the femoral trial is measured in the AP plane while the knee is in flexion. Often a wedge can be used to anteriorize the femoral trial. This ensures that the femur is placed in an appropriately anterior position. From this starting point, the goal is to stay within about 10–15° of varus-valgus angulation of the tibial surface so as to not edge load the final construct. The femoral trial can be moved medial or lateral depending upon coverage so long as the nose of the trial does not point into the trochlear groove, as this could cause patellar impingement. Avoiding excessive internal rotation is important as this will bring the posterior aspect of the femoral component too medial in extension (Fig. 27–12). Most surgeons aim for slight external rotation of the femur relative to the tibial cut in flexion. The actual rotation of the femoral component is dependent upon the type of implant used. If the system is a round-on-flat design, as most are, there is some forgiveness in the orientation of the femur. If, on the other hand, the system is a fully congruent one, this orientation is critically important. Most UKA systems have trials to ensure appropriate femoral-tibial alignment, tracking and balance.

Tibial Sizing and Preparation

With the meniscal fragment removed and the femoral cuts done, the tibial plateau can be more easily visualized (Fig. 27–13). For an all-poly tibial component, it is more important to have good AP coverage than medial-lateral coverage. This gives the tibial insert the best support. If necessary, it is possible to cut more into the medial aspect of the tibial spine, which in effect lateralizes the tibial component and allows for a larger size if needed. Slight overhang medially is tolerated on the tibia, and this is preferable to cutting too far into the tibial spine, which could potentially destabilize the insertion of the ACL. For an inlay tibial component, leaving a rim of bone for cement containment is important and leaving a base of sclerotic bone is helpful for tibial support.

Final Balance Check and Trial Reduction

Once all bone preparation is complete, this is the time to perform a trial reduction (Fig. 27–14). Most systems have adequate trials for insertion, but if not, the real components can be used; however, it is important to remove them carefully after the trialing so as to not scratch their surfaces. A trial reduction will be helpful in determining the amount of flexion necessary to seat the components and also allows for final soft tissue balancing. It is possible to do slight adjustments to the medial soft tissues if the knee is too tight in both flexion and extension, although it is not recommended to perform a large medial release in the UKA knee.

Cementation

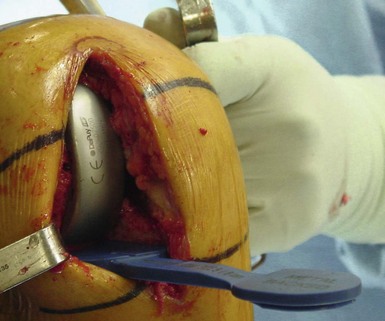

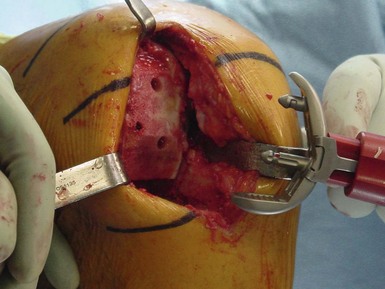

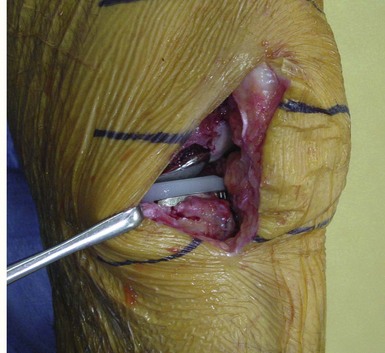

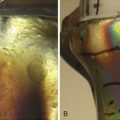

Retained cement is a relatively common cause for early reoperations in UKA. Removal of all cement fragments is very important. Smaller incisions limit visibility, and insertion of the tibial component in particular has the tendency to push cement out the back of the knee. This is particularly a problem with all-poly tibial components. Placement of a sponge behind the knee during cementation is one way to help prevent this from occurring (Fig. 27–15). Avoiding too much cement on the posterior aspect of the tibia is another. It is important to recognize that it is possible to have the front of the tibia in contact on the anterior tibial bone at the same time that the posterior part of the component is actually extended and not seated. The best way to prevent this is to insert the tibia in a hyperflexed position and to engage the back of the tibial implant on the tibia and to then bring the anterior edge of the tibia down. This can have the effect of pushing the cement anteriorly rather than out the back of the joint. It is important to inspect along the medial aspect of the knee to see that the posterior aspect is, in fact, in contact with the tibia. On the femoral side, good cement penetration onto the femoral surface is imperative. If sclerotic bone persists after bony prep, small drill holes can be helpful in improving the interdigitation. Most femoral components have lugs, and good cement compression into these lugs is also important to prevent femoral loosening (Figs. 27–16, 27–17, and 27–18).

Conclusion

UKA is generally thought to be a more technically difficult surgery. In particular, in comparison to a TKR, the smaller incision usually used in UKA and the fact that the surgeon must mate the replaced compartment to the remaining tibial plateau are two reasons for the increased technical difficulty. However, if the surgeon is careful in patient selection, follows a meticulous surgical technique, and utilizes a well-designed implant, UKA can provide an excellent option for the patient with isolated compartment disease (Fig. 27–19).

1 Kozinn SC, Scott R. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1989;71:145-150.

2 Pennington DW, Swienckowski JJ, Lutes WB, Drake GN. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients sixty years of age or younger. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2003;85:1968-1973.

3 Parratte S, Argenson JN, Pearce O, et al. Medial unicompartmental knee replacement in the under-50s. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2009;91:351-356.

4 Deshmukh RV, Scott RD. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:272-278.

5 Naal FD, Neuerburg C, Salzmann GM, et al. Association of body mass index and clinical outcome 2 years after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:463-468.

6 Tabor OBJr, Tabor OB, Bernard M, Wan JY. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: long-term success in middle-age and obese patients. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2005;14:59-63.