Chapter 26 PRACTICAL ISSUES IN NUTRITION AND SUPPLEMENTATION IN GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASE

NUTRITIONAL PROBLEMS

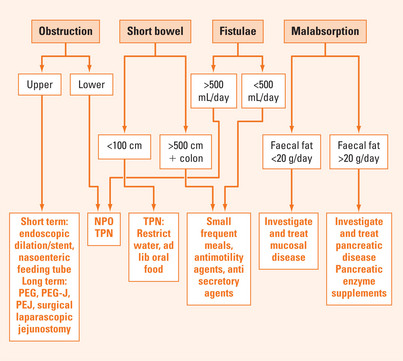

Management options for various nutritional problems are summarised in Figure 26.1.

Intestinal obstruction

Short bowel

Traditionally, the short bowel syndrome has been defined by the loss of all but 200 cm of small intestine, bearing in mind that the average length of the small intestine is 4 metres. However, this is imprecise as function will be influenced by whether the colon is remaining or not, and whether the residual small intestine is healthy. It has been estimated that the colon represents another 100 cm of small intestine after adaptation (which can take up to 2 years), and colonic salvage of maldigested food can result in the absorption of a further 1000 kcal/day. Clearly, 200 cm of residual intestine with active Crohn’s disease will not be equivalent to 200 cm of previously healthy mucosa. The most sensitive measure of remaining intestinal absorptive capacity is citrulline synthesis. Citrulline synthesis, and hence the functional bowel length, can be estimated from the fasting plasma citrulline concentration, which helps overcome errors in measurement of diseased bowel at surgery.

Intestinal failure

The first loss of function is the capacity to reabsorb secretions, resulting in fluid and electrolyte depletion, or ‘dehydration’. It is only if <200 cm of small intestine and no colon remains that intravenous (IV) supplementation becomes necessary, and a state of ‘small bowel intestinal failure’ is said to exist. The same is true if <50 cm of small intestine remains with an intact colon, and TPN or home TPN then becomes essential for survival.

Measurement

The patient excretes less that 1000 mL urine and <5 mmol of sodium when on a normal diet.

Tailoring TPN

Malabsorption

Malabsorption is conventionally divided into conditions that interfere with:

Classic examples of diseases that interfere with mucosal function are coeliac disease and inflammatory and infiltrative disorders. Because such disorders are often patchy and because there is a redundancy of absorptive area, these diseases result in lower grades of malabsorption than diseases that impair digestive function, such as pancreatic diseases. It is therefore useful to measure the degree of fat malabsorption: in general mucosal disease results in fat malabsorption of <20 g/day, while pancreatic malabsorption usually causes losses >20 g/day. It is, however, extremely important to measure fat malabsorption accurately: it is amazing how frequently stool fats are measured in patients who are on restricted diets or even TPN, in which case such cut-off numbers are meaningless.

Management

Mucosal malabsorption can often be controlled by simply increasing the oral intake. Although this will inevitably increase stool losses initially, the proportion absorbed remains the same and so the quantity retained will increase. This is even true for vitamin B12 malabsorption in pernicious anaemia, as there is also a less efficient passive absorption mechanism. The ways of increasing nutrient intake is the same as those outlined above for the management of short bowel syndrome. For pancreatic malabsorption, commercial pancreatic enzyme supplements should be used. It must be remembered that the output of proteinaceous enzymes by the healthy pancreas is extremely large particularly during eating, approximately 20 g/day, and so enzyme supplementation has to follow a similar pattern and frequency (e.g. four capsules with meals and two with snacks). Much effort has been put into designing effective preparations that are not inactivated by gastric acid, that migrate with food through the pylorus and are only released on entering the duodenum. Despite this, it is rare to completely reverse steatorrhoea, but the improvement is usually sufficient to prevent further weight loss.

SUMMARY

In the management of intestinal fistulae the volume of output provides a good index of the site of the fistulae. Treatment for low output fistulae (ileocolonic) is not TPN, as luminal nutrition helps the bowel to recover, and oral feeding should continue with IV supplementation.

Kaushik N, Pietraszewski M, Holst JJ, et al. Enteral feeding without pancreatic stimulation. Pancreas. 2005;31:353-359.

Matarese LE, O’Keefe SJ, Kandil HM, et al. Short bowel syndrome: clinical guidelines for nutrition management. Nutr Clin Pract. 2005;20:493-502.

Mullady DK, O’Keefe SJ. Treatment of intestinal failure: home parenteral nutrition. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:492-504.

O’Keefe SJ, Buchman AL, Fishbein TM, et al. Short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure: consensus definitions and overview. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:6-10.