Section 2 Practical Guidelines for Injection Therapy

Overview

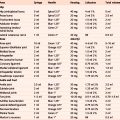

In this section we emphasize the necessity of being able to fully understand the information the patient is imparting in the history, to clearly interpret the signs and symptoms elicited in the examination and finally, to eliminate the various differential diagnoses to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. Only in this way can one successfully achieve the desired result of selecting the patient who might respond to injection therapy (Table 2.1). This, combined with an in depth knowledge of functional anatomy, should enable the clinician to help relieve the many patients with pain from musculoskeletal lesions.

Table 2.1 Indications for corticosteroid injections, with or without local anaesthetic

How to use this book

Equipment

Syringes

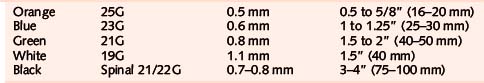

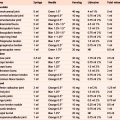

All needles and syringes must be of single-use disposable type and must be checked to ensure they are in date. Have available 1 ml, 2 ml, 5 ml, 10 ml and 20 ml sterile syringes; occasionally a 50 ml syringe might be necessary for aspiration (Table 2.2).

The drugs

Local anaesthetic

Lidocaine with epinephrine, which comes in ampoules or vials clearly marked in red, should not be used because of risk of ischaemic necrosis in appendages (page 16). Because of its potential half life of 8 hours or more, we do not recommend the routine use of Marcain but occasionally it can be used when a longer anaesthetic effect is needed. Some practitioners like to mix short- and long-acting anaesthetics to gain both the immediate diagnostic effect and the longer therapeutic effect.

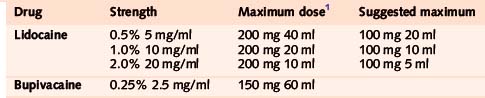

Dosages

It is important to keep within the recommended maximum doses of local anaesthetic in order to avoid toxicity. The safe maximum doses we suggest are given in Table 2.3. These doses are half the maximum published in pharmacological texts, so are well within safety limits (BNF).

Volumes

The volumes suggested in Table 2.3 are well within safety limits and will not cause the joint capsule to rupture; for instance it is not unusual to aspirate over 100 ml of blood from an injured knee joint. In any case, the back pressure created by too large a volume would blow the syringe off the fine needle recommended, long before the capsule was compromised (Table 2.4).

Table 2.4 Joint injections: suggested average doses and total volumes

| Joint | Dose | Volume |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder | 40 mg | 5 ml |

| Elbow | 30 mg | 4 ml |

| Wrist | 20 mg | 2 ml |

| Thumb | 10 mg | 1 ml |

| Fingers | 5 mg | 0.5 ml |

| Hip | 40 mg | 5 ml |

| Knee | 40 mg | 5 to 10 ml |

| Ankle | 30 mg | 4 ml |

| Foot | 20 mg | 2 ml |

| Toes | 10 mg | 1 ml |

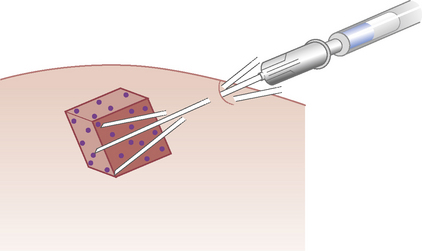

Conversely tendons should have small volumes injected. This avoids painful distension of the structure and minimizes risk of rupture. An average ‘recipe’ for tendons is given in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5 Tendon injections: suggested average doses and volumes

Technique

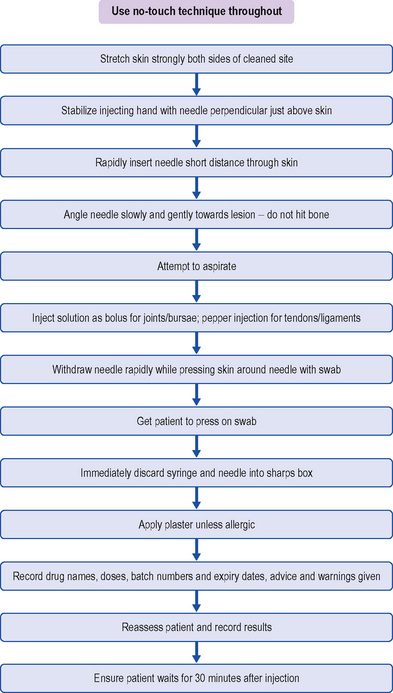

We describe a logical sequence for administration of the solution, and ways of performing a safe and relatively painless injection (Table 2.6).

| The following simple precautions should be taken to prevent the occurrence of sepsis: |

Wet hands carry more risk of infection so hands must be well dried before injecting – see the technique recommended by the World Health Organization.2,4–7 Gloves are mandatory in some countries; we recommended wearing gloves when aspirating, but they do not need to be sterile.8

Aspiration

Aspiration can be planned or unplanned. Planned aspirations are common for the knee joint, olecranon bursa, Baker’s cyst and ganglia. If the area, for example the knee joint, looks swollen or feels warm, fluid will be present and aspiration is a strong possibility, so the equipment can be prepared (Table 2.7). Occasionally, when drawing back on the plunger, unexpected aspiration occurs. To be ready for this, it is useful to have a large syringe and needle to hand when injecting large joints.

Aftercare

Advise the patient on what to do and what to avoid in the intervening period. Joint conditions usually benefit from a programme of early gentle movement within the pain-free range9; studies have shown that 24 hours’ complete bed rest after a knee injection for inflammatory arthritis is beneficial but in the case of the wrist immobilization does not appear to improve outcome and might even worsen it. Overuse conditions in tendons and bursae require relative rest; this means that normal activities of daily living can be followed, provided they are not too painful, but return to sport or strenuous repetitive activity should be postponed until the patient is as pain free as possible.

Contraindications to injection therapy

1. British National Formulary, No 59. London: BMA/RPSGB. 2010:766. March

2. Cawley P.J., Morris I.M. A study to compare the efficacy of two methods of skin preparation prior to joint injection. Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31:847-848.

3. Lawrence J.C., Lilly H.A., Kidson A., et al. The use of alcoholic wipes for the disinfection of injection sites. J Wound Care. 1994;3:11-14.

4. WHO. WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care (Advanced Draft). Geneva: WHO. 2006:101. World Alliance for Patient Safety

5. Smith R.W., Campbell M.J., O’Connell S., et al. Methods of skin preparation prior to intra-articular injection, (letter). Br J Rheumatol, 32;7. 1993: 648.

6. Handwashing Liaison Group. Hand washing. Br Med J. 1999;318:686.

7. Hartley J.C., Mackay A.D., Scott G.M. Wrist watches must be removed before washing hands, (letter). Br Med J, 318. 1999: 328.

8. Courtney P., Doherty M. Joint aspiration and injection and synovial fluid analysis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23(2):161-192.

9. Chakravaty K., Pharoah P.D.P., Scott D.G.I. A randomised controlled study of post-injection rest following intra-articular steroid therapy for knee synovitis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:464-468.