19 Practical Aspects of Communication

Being able to effectively talk to children honestly about their physical status and illness, their treatment, and their prognosis in ways that are matched with their age, maturation and clinical situation is expected of clinicians.1–5 This expectation spans all clinical settings from primary care to emergency care6,7 unless there are extreme circumstances such as a parent or legal guardian forbidding that kind of talk8,9 or the treating culture is opposed.10 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has produced a technical report, which states communication competency that includes cultural effectiveness is part of the ideal standards of behavior and professional practice for pediatricians.11 The AAP also issued a policy statement indicating that primary care pediatric clinicians need to be able to elicit concerns from children within their cultural context.7 Even more specifically, professional specialty associations have issued position papers making explicit the expectations that clinicians will be willing and able to effectively and compassionately share information with a child regarding the nature of the child’s illness, the type, duration and likely experience and outcomes of its treatment, and to be readily available to revisit the discussion as the child signals need.

What Is Effective Communication?

Effective communication is the making of a human connection with a child and family. The transmission of information, while essential, is by no means the only role of effective communication. In addition, the communication encounter serves as the foundation for a relationship that unfolds over time. Communication provides the clinician with the opportunity to learn about the child and family: who they are as people, their beliefs and sources of support, the meaning of the illness in their lives, their needs, their goals, their hopes, and their fears. As such, vital roles by the clinician include listening and eliciting information in the encounter. Resulting knowledge allows the clinician to communicate in a way that is helpful for this child and family, to provide care specifically tailored to them, and to consider who they are as people along the illness trajectory. This knowledge serves as a foundation for effective decision making and as a foundation for a meaningful therapeutic alliance, which in itself can support end-of-life decision making.12 Much of this can be achieved not through the use of particular words, but through caring interaction among the child, family, and clinician. Although the language used matters,13 the emerging clinician-child-parent relationship matters more. Therefore, although specific words and phrases may be considered as possible tools for these conversations, clinicians who approach these encounters with a sincere desire to listen and get to know the child and family, and to be trusted by them, are likely to be the most successful.

Why is effective communication important in pediatric palliative and end-of-life care?

Additionally, providing children with information about their diseases and treatments meets legal regulations and ethical considerations8,17 in terms of assent and consent. Finally, carefully communicated information about illness and treatment can also promote self-care behaviors in the ill child, such as learning to recognize and avoid high-risk situations,18 and promote child participation in treatment decision making.16,19,20 On the other hand, insensitive or incomplete communication is reported to be distressing to the pediatric patient and his or her family, including the siblings.21

What are the guiding principles of communicating effectively with the seriously ill child and family?

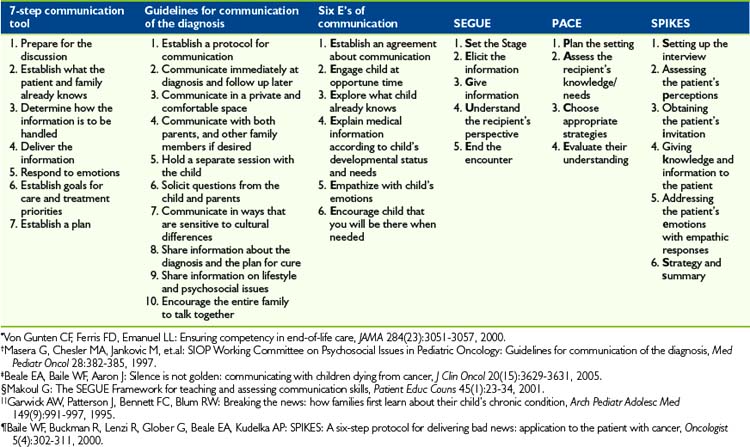

The complexity of communicating with seriously ill children is well recognized by clinicians and is underscored in their reported anxiety about discussions with these children and their families.4,22 Perhaps as a direct result of the complexity and importance of communicating with children and families, clinicians have created guides and principles intended to assist in their efforts to communicate with children (Table 19-1). The first principle of communication between a child and a clinician is that the communication needs to always take place within a family context.23 Families enter into an illness experience with a style of communication already in place. Effective communicators recognize that parents and guardians are the most knowledgeable about their child and are thus the experts about the child24 (Box 19-1).

BOX 19-1 Principles of Communication with a Seriously Ill Child and the Child’s Family

Just as every family is different, children and families experience illness in their cultural context, and medical communication should be sensitive to the differences in information needs and decision-making styles. Although many clinicians in the United States prefer to provide information about diagnosis or prognosis, internationally this is not always the case, and in part these clinician traditions reflect the pervading beliefs and preferences of the families in those areas.10,25 Whenever possible, clinicians should accept the standards within a family. Some knowledge of the family’s culture of origin may be helpful; cultural brokers, for example, may be able to offer insight into general standards of communication and areas that are particularly different or sensitive.26 However, assumptions about the meaning of culture in a particular family should be avoided.26,27 The clinician’s best tool for learning about communication within a family is often humility; a willingness to ask about the way the family likes to communicate and make decisions should be accompanied by an openness to respect that family’s style.

Parents can vary in their preferences for who shares serious information with their child. Some may prefer that a trusted clinician have these discussions alone with the child or in the presence of the parents; while other parents may not want the clinician to be the one to initiate certain discussions with their child. They may prefer to initiate the discussion themselves. In the latter case, there remain important roles for the clinicians, including preparing parents for the discussions with their child and being well informed or even present when the parents share information with their ill child. There may be a natural parent reluctance to share serious information with their child.28 Reluctance could include fear of the child’s emotional reaction, loss of hope about the situation, or diminished willingness on the child’s part to interact with the parents and others. Clinicians can help prepare parents for these discussions by exploring underlying reasons for concerns, offering suggestions for possible ways to share the information or even role-playing with the parents in advance of the discussion. Parents have indicated that after they or the clinicians have serious conversations with their child, they want clinicians to treat their child the very same as before the child’s condition became more serious.29

The second guiding principle is that communication is making a human connection. Literature offers instructions on how to deliver bad news.30,31 These are helpful tools but the most central point to effective communication between a clinician and a child is the intention to make a human connection in which honest information and feelings are shared. Clinicians are first providing care for a person, and then for the person’s condition.6

The third guiding principle is to thoughtfully prepare for sharing information and feelings. As noted in Table 19-1, the guidelines for communication include steps to assure that all relevant individuals are included in the discussion. It is also important that a quiet setting is available for an uninterrupted discussion and that to the fullest extent possible no anticipated interruptions occur, instead ask a team member to handle the pagers for those who will be in the discussion. Openness to conversation is particularly important. With children, an open invitation to talk should be accompanied by careful listening for cues that the time is right. A clinician who is too busy when such glimpses into a child’s thoughts occur may miss important opportunities. In addition, clinicians may wish to create opportunities for interaction including quiet presence on a regular basis, not just when there is medical news to be delivered. The spaces between the news may be rich with meaning that informs all other interactions. Presence also sends a powerful message about the consistent caring the clinician provides and the value of the child and family.

The fourth guiding principle is that communication is never a one-time event but is instead ongoing,32 with the clinician being attuned to clues from the child about information needs. In addition to being sensitive to clues from the child, it is helpful when the clinician directly offers to revisit a topic or conversation or specifically solicits questions about any aspect of care. Communication is not limited to when a change in the child’s condition or treatment is occurring, but it is especially critical for such times. Children find it helpful when clinicians address how the clinical change occurred, if this can be determined, and particularly for the younger child, when clinicians clearly state that the child is not to blame for the change.3

The fifth guiding communication principle is for the clinician to get invited by the child to engage in sharing information, thoughts, and feelings. Clinicians will seek the invitation through their unique styles that develop over time; some may do it directly, others using a metaphor or vehicle such as sports, play items, or books. The likelihood of being invited is increased from the point of diagnosis forward when the clinicians tell the child about their willingness to keep the child informed and to answer questions. Being invited signals respect for the child, as it allows the child to decide the timing for the exchange of information, ideas, and feelings. This is taking time to establish a relationship and a rapport and seeking to build a partnership between the clinician and the child.16

A sixth guiding principle is there are times when a single mode of communication will be insufficient with a child or the family. Helpful examples of verbiage have been published.3,33 Other forms of media can also be very helpful in sharing information and feelings between clinicians and children include drawings.34 Perhaps one of the most powerful of communication tools that a clinician can use is silence. Clinicians must be able to quiet their own thoughts and not try to plan their next comment but instead listen with the intention of discovering an insight about this child, family, situation, or about self.35 Listening without interruptions is a very sophisticated skill and one that is least-frequently practiced by clinicians. Communication is sharing information and feelings that is intended to be understood in the same way by the child and the clinician and most typically requires more than one method. Whatever mode is selected for communication, the endpoint goal is the same: The child and parents will feel listened to and respected.36

What transpires during the discussion is important, and what transpires after the discussion is as well. Commonly, some members of the interdisciplinary team are present during the discussion without leading the conversation. These team members may insert comments meant to clarify content and confirm the child’s understanding.37 Following the discussion, individual team members may linger with the patient and family or return subsequently to encourage the child and family to ask questions.38 Careful documentation of all of these exchanges is needed so that all clinicians can be well informed and not need to ask the family to repeat to them what transpired. One professional organization, the SIOP Working Committee on Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology, recommends that a communication protocol be created for each healthcare setting that contains the expected behaviors of each member on the clinical team for communication including that related to diagnosis.4 In addition to providing the family with the opportunity to reflect on the conversation afterward, interdisciplinary team members may actively participate by observing interactions carefully, recognizing and attending to emotional content, and being alert to miscommunications. These roles may be difficult for the clinician who is leading the conversation to fully take on. The team can also serve as a source of support to one another, working together to reflect on these encounters and helping one another feel sustained in this difficult work. Finally, team members have a role in simply witnessing these profound discussions. Even if some members of a team don’t say a word in a family meeting, simply by being present they convey a message that the conversation is important and meaningful and that the child and family are as well.

When communication efforts do not go well

Clinicians should remember to be forgiving of themselves in such encounters as well. Much of the time, difficult encounters are not a result of a thoughtless or unskilled clinician, but rather the result of a situation that is painful for the clinician. Clinicians who have difficulty talking with the child about diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis are likely struggling themselves with the sad clinical situation.39,40 All clinicians need support during these difficult times but clinicians who avoid communicating honestly with children need immediate support from other members of the healthcare team and particularly from a senior clinician who has recognized abilities to communicate well with seriously ill children, a willingness to demonstrate those abilities and who has respect for fellow clinicians who do not yet have such skills.

Specific Palliative Care Communication Topics

Sharing information about prognosis

Much of the literature on communicating about advanced illness comes from studies of adults with metastatic cancer, in which the disease course is often relatively predictable and typically involves a progressive decline from diagnosis to death. For children with life-threatening illnesses, however, the trajectory can be unpredictable, often lasting over many years, and marked by exacerbations and reprieves from symptoms.28 For families and children who experience these long, complex illnesses, the ups and downs of illness can make the larger picture difficult to fathom. It is particularly important, then, for clinicians caring for the child to help the child and family understand what the future may hold, so that appropriate decisions can be made all along the trajectory.

One aspect of this is communicating about the child’s prognosis, including the possibility of death and when that may occur. Previous literature suggests that physicians are often reluctant to discuss prognosis with patients, in part because they worry about causing distress and taking away hope.41–45 Yet parents tend to have less distress when they have received the information they want about prognosis,46,47 perhaps because such information gives them a sense of some control over the situation and alleviates uncertainty, which itself can be extremely upsetting. In addition, parents often want prognostic information, reporting that accurate prognostic information helps them to make the best possible decisions for their children.47

Evidence from the adult cancer setting suggests that prognosis communication does affect end-of-life decision-making. For example, adult patients with metastatic cancer who have unrealistic expectations about a long lifespan are more likely to choose life-prolonging therapy over comfort-directed care.48 Similarly, adult patients with advanced cancer who report having discussed their wishes for end-of-life care with a physician are less likely to use mechanical ventilation, resuscitation, or care in the intensive care unit at the end of life, and are more likely to enroll in hospice care.49 Although it is possible that some patients will continue to desire life-prolonging care at the end of life, communication about the expectation that death is likely to occur allows patients to make decisions based on their own values, and not on unrealistic expectations.50,51

In addition to the importance of having discussions about the possibility of death, the timing of such discussions is also important. There are reports that bereaved parents’ understanding that their children with cancer had no realistic chance for cure tended to lag behind physicians’ knowledge of the child’s incurability by several months.14 Earlier parental recognition of the child’s limited chance of cure was associated with earlier discussions about hospice care, earlier institution of do-not-resuscitate orders, and decreased use of cancer-directed therapy at the end of life.14

Similarly, in a study of 318 bereaved family members of adults who had died of cancer, half believed that palliative care services were provided later than they would have wanted, while less than 5 % believed that referrals for palliative care were provided too early. Families were more likely to say palliative care was instituted too late when they also reported feeling inadequately prepared for changes in the patient’s medical condition and when they believed that discussion about end-of-life care preferences with physicians was insufficient, suggesting that communication about a poor prognosis and institution of palliative care often jointly occur late in the disease course.52

Despite the potential benefits of early conversations about a child’s life-limiting condition, the diversity of life-limiting illnesses in pediatrics means that the perceived optimal timing of referrals to palliative care varies widely among pediatricians.53 Pediatric clinicians report feeling inexperienced with communication about end-of-life issues, including transitions to palliative care and resuscitation status,40 and this inexperience may also lead to delays in such communication.

Clinicians may also be faced with uncertain clinical situations, in which the timing of death or even whether death is expected cannot be determined with certainty. Communication is particularly challenging in this setting, but even so an honest conversation about possible outcomes can be important to families. Previous work has suggested that clinicians tend to give no information or overly optimistic information to patients and families in uncertain times.54,55 However, just as in situations where the prognosis is known with greater certainty, an honest estimate may best allow families to prepare for possible outcomes. The clinician may also wish to discuss a range of possible outcomes but, again, with honesty and not with undue optimism.

Applying a framework for communicating effectively about prognosis

Clinician inexperience or anxiety can lead to delays in communication about prognosis. Offered here is a framework for talking about prognosis and plans for care in the end-of-life period with a child and family. This framework is presented in the context of the SPIKES format described in Table 19-1. However, there is no single way of holding this discussion, and as always the most important element is the caring child-parent-clinician relationship that forms the context for this discussion. A second vitally important aspect of the discussion is tailoring the information and its presentation to the needs of the child and family, a strategy that can best be enacted by eliciting their preferences and needs and by listening carefully. There are six steps to this process:

Applying a framework for communicating effectively about palliative and end-of-life care goal-setting

The child’s and parents’ goals of care form the foundation of the care plan. Once goals are defined, all decisions about care can be considered in light of these goals, with the clinician and family jointly considering the extent to which specific interventions meet the desired goals or not. Involving the child and family in care goal-setting from the point of diagnosis or injury forward provides opportunities for them to become accustomed to this aspect of care. This can also avoid only using goal-setting at the end of life, when such a shift in language could be disconcerting for the child and family. Goal-setting has also been associated with facilitating patient-family-clinician general communication and trust58 as well as future decision making.59

Goal-setting is influenced by the child and parents’ and clinical team’s understanding of the child’s prognosis, suffering and care preferences.60–61 Because goals can change over time, reassessment is important.33 In addition to changing goals, children and their parents may change their preferences for involvement in goal setting and related decision making. This change can range from having been somewhat involved at one point in care to becoming directive or passive in other points in care. Differences in preference for involvement may also differ in geographically distinct parts of the world thus making it important for clinicians to be responsive to the child’s and parent’s preferences for involvement.62–64

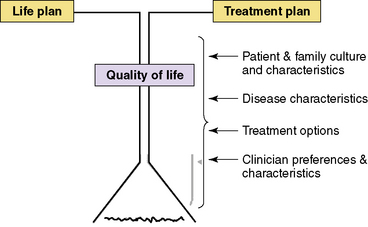

Goal-setting discussions include two major foci: goals for the life plan and for the treatment plan.65 The life-plan goals are related to personal values, priorities, and commitments whereas treatment goals are related to medical-care priorities. Together, the goals from these directly influence the child’s quality of life (see Fig. 19-1). The life-plan goals and the treatment goals, though both of primary concern, are not necessarily in equal balance with each other as at times one or the other may carry more weight. However, consideration of both concurrently throughout palliative care will help achieve quality of life considerations for the seriously ill child. Certain categories of factors influence goal-setting discussions about the life plan and the treatment plan, including characteristics of the child and the parents such as family culture and communication style; the child’s injury or acute or chronic illness; treatment options; and characteristics and values of the clinical care team members. When discussing life plans and treatment plans, it is important to have the primary physician present, because the majority of parents report that physicians are the primary source of information for them about their child’s clinical status and prognosis. No single member of a team can be expected to lead all goal-setting discussions as a different team member may be more informed or familiar with a patient’s or parents’ unique style of communication and thus would more expertly facilitate the discussion for that family. Another reason to have multiple team members skilled at facilitating goal-setting discussions is that a member of a team may be unable to serve in that way at certain times and for a number of reasons, not the least of which is a deep sadness about the child’s circumstances. It is important for each clinical team to be able to examine their abilities and strengths in communicating with patients, parents, and each other about care goals.

Hope and reality as frameworks for parenting at the end of life

As an example, researchers found that parents of children who have died of cancer tend to express dual goals of using cancer-directed therapy to extend life and symptom-directed therapy to address the child’s suffering or symptoms.14,68 Instead of seeing these goals as conflicting, parents may find care that addresses both sets of goals to be most comfortable. The clinician may wish to allow for a range of goals when communicating with the parents, and may wish to explore hopes and perceived reality as separate but complementary aspects of the parents’ present. Some have recommended allowing for hopes by talking about end-of-life care in a hypothetical manner with patients who have a great deal of difficulty accepting death as a likely reality.69 This strategy, termed “hope for the best, prepare for the worst,” can allow for end-of-life care planning concurrent with the hope that such plans will not be necessary.69

In addition, hope may not always be focused on cure or a long life.57 A previous study evaluated the extent to which discussion about a child’s prognosis affected the parents’ sense of hope for their children with cancer. Strikingly, parents who had received more extensive prognostic information were also more likely to report that communication had made them feel hopeful, even when the child’s prognosis was poor.55

This study raises the possibility that knowledge of a poor prognosis can actually increase hope. Although this relationship seems counterintuitive, recent literature affirms the possibility that clinician honesty, even about difficult news, can help patients to feel more hopeful. For example, 126 patients with metastatic cancer were surveyed about physician behaviors they considered to be hope-giving. Realistic communication about prognosis was considered by the majority of patients to be hope-giving; communicating in euphemistic terms or avoiding honest disclosure of bad news, on the other hand, engendered more hopelessness.70 Along similar lines, a study of surrogate decision makers for patients receiving mechanical ventilation revealed that 93% of surrogates considered avoidance of discussion about prognosis to be an unacceptable way to maintain hope.71

The reasons that hope may be enhanced by honest communication of difficult issues are not understood, though there are some possible explanations. First, knowledge of a poor prognosis could relieve the anxiety of uncertainty about the future. Others have reported that the experience of uncertainty about one’s medical situation can result in a diminished sense of hope.72 In contrast, clear communication about the illness and its expected trajectory may positively impact adjustment to illness and the individual’s sense of hope. Among adult patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis, receipt of information, including prognostic information, allowed for a sense of empowerment about medical care and decision making, which was in turn an important component of hope. Because many patients relied on physicians to initiate discussions about advance care planning, however, fears for the worst possible outcomes sometimes threatened hope when discussions did not take place.73

A second possible explanation is that direct acknowledgement of a life-limiting condition allows patients to formulate alternative hopes not focused on the disease.57 Because most previous studies have assessed the general experience of hope without examining what hope means, an assumption that hope equals hope for a cure has persisted in the medical literature and in the minds of many clinicians. However, if prognosis communication can support hope, then hope must be broader than hope for a cure. Hope may encompass life-prolongation or palliation, or broader hopes that are focused on meaningful relationships, beliefs, and experiences. The formulation of hopes not focused on the disease could be a component of finding meaning in the end-of-life experience. Among adolescents with cancer, for example, hope has been defined as a belief in a “personal tomorrow” with highly individual meanings.74

Finally, it is possible that hope can be derived from the communication interaction itself. It may not be the discussion of difficult issues itself that provides hope, but the fact that the discussion occurs in the context of a caring parent- child-clinician relationship. A 2008 editorial speaks to this issue by describing hope as an experience related to caring, consolation, relief from disquiet, and meaning in relationships. This definition suggests that the clinician may have a meaningful role to play in the development and maintenance of hope, and that this role emanates from a caring, human connection between caregiver and patient.75

Communicating Effectively About What to Expect When Death Is Near

While medical caregivers ensure detailed communication with parents and children about side effects and expected symptoms during self-limiting illnesses, clinicians may find that conversations about the child’s experience when death is imminent may be too difficult to broach. This sympathy with the pain parents may experience at such conversations can lead clinicians to avoid providing detailed information about how the death may unfold. For parents, however, receipt of information about what to expect at the end of life is a component of high-quality care.76,77 The deep pain parents experience in such conversations may be outweighed by the need to know what is ahead, and in knowing this, to gain some sense of control over an uncontrollable situation.

Applying a framework for communicating effectively about what to expect at end of life

1 Goldie J., Schwartz L., Morrison J. Whose information is it anyway and informing a 12-year-old patient of her terminal prognosis. J Med Ethics. 2005;31:427-434.

2 Levetown M. Ensuring that difficult decisions are honored—even in school settings. Am J Bioeth. 2005;5(11):78-81.

3 Hurwitz C.A., Duncan J., Wolfe J., et al. Caring for the child with cancer at the close of life: “There are people who make it, and I’m hoping I’m one of them,”. JAMA. 2004;292(17):2141-2149. doi:10.1001/jama.292.17.2141

4 Masera G., Chesler M.A., Jankovic M., et al. SIOP Working Committee on psychosocial issues in pediatric oncology: guidelines for communication of the diagnosis. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:382-385.

5 Ranmal R., Prictor M., Scott J.T., et al. Interventions for improving communication with children and adolescents about their cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2009. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD002969.pub2

6 O’Malley P.J., Brown K., Krug S.E., et al. Patient- and family-centered care of children in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 122(2), 2008.

7 Garwick A.W., Patterson J., Bennett F.C., Blum R.W. Breaking the news: how families first learn about their child’s chronic condition. Arch Pediatr Adolescent Med. 1995;149(9):991-1107.

8 Freyer D.R. Care of the dying adolescent: special considerations. Pediatrics. 2004;113:381-388. DOI: 10.1542/peds. 113.2.381

9 Gupta V.B., Willert J., Pian M., Stein M.T., et al. When disclosing a serious diagnosis to a minor conflicts with family values. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(3):231.

10 Parsons S.K., Saiki-Craighill S., et al. Telling children and adolescents about their cancer diagnosis: cross-cultural comparisons between pediatric oncologists in the US and Japan. Psychooncology. 2007;16(1):60-80.

11 Fallat M.E., Glover J. Professionalism in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1123-e1133.

12 Mack J.W., Block S.D., Nilsson M., et al. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: the Human Connection Scale. Cancer. 2009;115(14):3302-3311.

13 Pantilat S.Z. Communicating with seriously ill patients: better words to say. JAMA. 2009;301(12):1279-1281.

14 Wolfe J., Klar N., Grier H.E., et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2469-2475.

15 Last B.F., van Veldhuizen A.M. Information about diagnosis and prognosis related to anxiety and depression in children with cancer aged 8–16 years. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(2):290-294.

16 Levetown M. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1441-e1460. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008–0565

17 Bradlyn A.S., Kato P.M., Beale I.L., Cole S.W. Pediatric oncology professionals’ perceptions of information needs of adolescent patients with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21(6):335-342.

18 Hinds P.S., Gattuso J.S., Mandrell B.N. Nursing care. In: Pui C.H., editor. Childhood leukemias. ed 2. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006:882-893.

19 Knafl K., Deatrick J.A., Gallo A.M., et al. The interplay of concepts, data, and methods in the development of the family management style framework. J Fam Nurs. 2008;14(4):412-428.

20 Snethen J.A., Broome M.E., Knafl K., Deatrick J., Angst D. Family patterns of decision making in pediatric clinical trails. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(3):223-232.

21 Contro N., Larson J., Scofield S., et al. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric pallative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:14-19.

22 Feudtner C., Santucci G., Feinstein J.A., Snyder C.R., Rourke M.T., Kang T. Hopeful thinking and level of comfort regarding providing pediatric palliative care: a survey of hospital nurses. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e186-e192.

23 Clarke S.A., Davies H., Jenny M., Glaser A., Eiser C. Parental communication and children’s behaviour following diagnosis of childhood leukaemia. Psychooncology. 2005;14(4):274-281.

24 Young B., Dixon-Woods M., Windridge K., Heney D. Managing communication with children who have a potentially life threatening chronic illness: children’s and parents’ accounts. BMJ. 2003;326:305-308.

25 Mystakidou K., Parpa E., Tsilila E., Katsouda E., Vlahos L. Cancer information disclosure in different cultural contexts. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12(3):147-154.

26 Surbone A. Cultural aspects of communication in cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(3):235-240.

27 De Trill M., Kovalcik R. The child with cancer. influence of culture on truth-telling and patient care. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;809:197-210.

28 Mack J.W., Wolfe J. Early integration of pediatric palliative care: for some children, palliative care starts at diagnosis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(1):10-14.

29 Barrera M., D’Agostino N., Gammon J., Spencer L., Baruchel S., et al. Health-related quality of life and enrollment in phase 1 trials in children with incurable cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2005;3(3):191-196.

30 Himelstein B.P., Jackson N.L., Pegram L. The power of silence. JCO. 2001;19(19):3996.

31 Mack J.W., Grier H.E. The day one talk. J Clin Oncol. 22(3), 2004.

32 Ishibashi A. The needs of children and adolescents with cancer for information and social support. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24(1):61-67.

33 Baker J.N., Hinds P.S., Spunt S.L., Barfield R.C., Allen C., Powell B.C., Anderson L.H., Kane J.R. Integration of palliative care practices into the ongoing care of children with cancer: individualized care planning and coordination. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55(1):23-50.

34 Rollins J.A. Tell me about it: drawing as a communication tool for children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22(4):203-221.

35 Rushton C.H. A framework for integrated pediatric palliative care: being with dying. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20(5):311-325.

36 Clark J.N., Fletcher P. Communication issues faced by parents who have a child diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 4;2003: 175-191. 2000

37 Ahmann E. Reviews and commentary: two studies regarding giving “bad news,”. Pediatr Nurs. 1998;24(6):554-556.

38 Mahany B. Working with kids who have cancer. Nursing. 1990;20(8):44-49.

39 Chanock S. Reflections on events surrounding the time of diagnosis in pediatric oncology. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23(4):211-212.

40 Contro N.A., Larson J., Scofield S., Sourkes B., Cohen H.J. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248-1252.

41 The A.M., Hak T., Koeter G., van Der Wal G. Collusion in doctor-patient communication about imminent death: an ethnographic study. BMJ. 2000;321(7273):1376-1381.

42 Gordon E.J. Daugherty CK. “Hitting you over the head”: oncologists’ disclosure of prognosis to advanced cancer patients. Bioethics. 2003;17(2):142-168.

43 Miyaji N.T. The power of compassion: truth-telling among American doctors in the care of dying patients. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(3):249-264.

44 Ruddick W. Hope and deception. Bioethics. 1999;13(3–4):343-357.

45 Kodish E., Post S.G. Oncology and hope. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(7):1817.

46 Mack J.W., Cook E.F., Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Cleary P.D., Weeks J.C. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1357-1362.

47 Mack J.W., Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Cleary P.D., Weeks J.C. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5265-5270.

48 Weeks J.C., Cook E.F., O’Day S.J., et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1709-1714.

49 Wright A.A., Zhang B., Ray A., et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673.

50 Block S. Psychological considerations, growth, and transcendence at the end of life. JAMA. 2001;285:2898-2905.

51 Lamont E.B., Christakis N.A. Complexities in prognostication in advanced cancer: “to help them live their lives the way they want to,”. JAMA. 2003;290(1):98-104.

52 Morita T., Akechi T., Ikenaga M., et al. Late referrals to specialized palliative care service in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2637-2644.

53 Thompson L.A., Knapp C., Madden V., Shenkman E. Pediatricians’ perceptions of and preferred timing for pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):e777-e782.

54 Christakis N.A., Iwashyna T.J. Attitude and self-reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(21):2389-2395.

55 Mack J.W., Wolfe J., Cook E.F., Grier H.E., Cleary P.D., Weeks J.C. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5636-5642.

56 Pollak K.I., Arnold R.M., Jeffreys A.S., et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5748-5752.

57 Hinds P.S. The hopes and wishes of adolescents with cancer and the nursing care that helps. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(5):927-934.

58 Eiser C., Jenney M. Measuring quality of life. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:348-350.

59 Varni J.W., Burwinkle T.M., Lane M.M. Health-related quality of life measurement in pediatric clinical practice: an appraisal and precept for future research and application. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:34.

60 Hays R.M., Valentine J., Haynes G., et al. The Seattle Pediatric Palliative Care Project: effect on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):716-728.

61 Klopfenstein K.J., Hutchinson C., Clark C., et al. Variables influencing end-of-life care in children and adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23(8):481-486.

62 Hinds P., Birenbaum L., Clarke-Steffen L., et al. Coming to terms: parents response to a first cancer recurrence. Nurs Res. 1996;45(3):148-153.

63 Hinds P.S., Oakes L., Quargnenti A., et al. An international feasibility study of parental decision making in pediatric oncology. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27(8):1233-1243.

64 Hinds P., Birenbaum L., Pedrosa A. Guidelines for the recurrence of pediatric cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2002;18(1):50-59.

65 Policy Statement—The Future of Pediatrics. Mental Health Competencies for Pediatric Primary Care. Amer Acad Pediatr. 124(1), 2009.

66 Carnevale F.A., Canoui P., Hubert P., et al. The moral experience of parents regarding life-support decisions for their critically-ill children: a preliminary study in France. J Child Health Care. 2006;10(1):69-82.

67 Sharman M., Meert K.L., Sarnaik A.P. What influences parents’ decisions to limit or withdraw life support? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(5):513-518.

68 Bluebond-Langner M., Belasco J.B., Goldman A., Belasco C. Understanding parents’ approaches to care and treatment of children with cancer when standard therapy has failed. JCO. 2007:2414-2419.

69 Back A.L., Arnold R.M., Quill T.E. Hope for the best, and prepare for the worst. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):439-443.

70 Hagerty R.G., Butow P.N., Ellis P.M., et al. Communicating with realism and hope: incurable cancer patients’ views on the disclosure of prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(6):1278-1288.

71 Apatira L., Boyd E.A., Malvar G., et al. Hope, truth, and preparing for death: perspectives of surrogate decision makers. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(12):861-868.

72 Hsu T.H., Lu M.S., Tsou T.S., Lin C.C. The relationship of pain, uncertainty, and hope in Taiwanese lung cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(3):835-842.

73 Davison S.N., Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2006;333(7574):886.

74 Hinds P.S. Inducing a definition of ‘hope’ through the use of grounded theory methodology. J Adv Nurs. 1984;9(4):357-362.

75 Harris J.C., DeAngelis C.D. The power of hope. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2919-2920.

76 Pritchard M., Burghen E., Srivastava D.K., Okuma J., Anderson L., Powell B., Furman W.L., Hinds P.S. Cancer-related symptoms most concerning to parents during the last week and last day of their child’s life. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1301-e1309.

77 Mack J.W., Hilden J.M., Watterson J., et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9155-9161.