Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome

Since the mid 1980s, there has been a tremendous increase in knowledge concerning illnesses that result from disturbances in the normal functioning of the autonomic nervous system. Initially, many of these investigations were principally focused on neurocardiogenic (or vasovagal) syncope, primarily as a consequence of the development of head upright tilt table testing as a method for uncovering a predisposition to the condition. During the course of these investigations, it became evident that a distant subgroup of patients experienced a related, yet distinct, autonomic disturbance that resulted in persistent orthostatic tachycardia and orthostatic intolerance.1 This disorder has come to be known as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and seems to consist of a heterogeneous group of disorders that share similar clinical characteristics. This chapter will present a review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of this disorder.

Autonomic Nervous System

In a healthy individual, close to 25% to 30% of the body’s blood volume is in the thorax while supine.2 Upon standing, the effect of gravity is to displace approximately 300 to 800 mL of blood downward to the abdomen and lower extremities. This is volume drop of 25% to 30% occurs in the first few moments of standing, resulting in a decline in venous return to the heart. As a result, the heart can pump only the blood that it receives, which produces a decline in stroke volume of approximately 40% and a decline in arterial blood pressure. The area around which these changes occur is known as the venous hydrostatic indifference point (HIP), and it represents the point in the vascular system where it is independent of position. The arterial HIP is near the level of the left ventricle, and the venous HIP is around the diaphragm.

Adequate maintenance of cerebral perfusion during upright posture is the product of the interaction of several cardiovascular regulatory systems. The exact changes that occur with standing (an active process) differ somewhat from those seen during head-up tilt (a more passive process). Wieling and van Lieshout2 have described three phases of orthostatic response: (1) the initial response (in the first 30 seconds), (2) the early steady state alteration (at 1 to 2 minutes), and (3) the prolonged orthostatic period (after at least 5 minutes upright).

Historical Perspective

By the middle of the nineteenth century, physicians began to report on a group of patients who had developed a disorder characterized by exercise intolerance, severe fatigue, and palpitations.3 These symptoms would often appear suddenly without a discernible cause such as prolonged immobility, blood loss, or dehydration. At the time of the American Civil War, DeCosta described patients suffering from postural tachycardia and orthostatic intolerance, a condition he called “irritable heart syndrome”.4

Around the time of the World War I, a condition referred to as neurocirculatory asthenia began to be reported. The most remarkable of these was a study by Thomas Lewis, who described a condition he called the “effort syndrome.”5 He stated that the fatigue was “an almost universal complaint” among these patients, as well as exercise intolerance in conjunction with symptoms such as palpitations, chest pain, syncope, and near syncope. In addition, Lewis reported that these patients demonstrated a significant postural tachycardia, with heart rates changing from 85 beats/min (bpm) supine to 120 bpm while upright. In some of these patients, there was a significant decline in blood pressure while upright, whereas others demonstrated only a modest decline.6 Lewis concluded that in these patients “the potential reservoir in the veins takes up the blood, the supply to the heart falls away, and the arterial pressure falls rapidly,” oftentimes accompanied by a compensatory tachycardia. Lewis further wrote that the reduction in blood flow “may be sufficient to produce cerebral anemia.”

Additional reports appeared,7,8 and this condition was later elucidated by Schondorf and Low, who performed extensive evaluations of 16 patients who suffered from extreme fatigue, exercise intolerance, bowel hypomotility, and lightheadness.9 During head-upright tilt table testing, these individuals displayed distinctly abnormal cardiovascular responses to upright posture, with heart rate elevations to as high as 120 to 170 bpm within the first 2 to 5 minutes of upright tilt. Some of these patients became hypotensive, but the majority remained normotensive, and a small percentage became hypertensive. In describing the condition, they used the term “postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome” (POTS).10 Later investigations have found that POTS is not a single entity; rather, it is a heterogeneous group of disorders with similar clinical characteristics.6,11,12

Definitions

Some patients can be so severely affected that the regular activities of daily life such as housework, bathing, and eating can greatly exacerbate symptoms. Studies have shown that some patients with POTS can suffer from the same degree of functional impairment as patients with congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Interestingly, the severity of the symptoms can be greater in patients with POTS than in those with more severe autonomic failure syndromes, such as pure autonomic failure. A grading system to classify the severity of orthostatic intolerance has been developed (similar to that used in congestive heart failure) as noted in Box 104-1.

Classification

In some ways, POTS is best considered as an abnormal physiological state (somewhat akin to the term heart failure) that can be caused by a wide range of different disorders. Although differing ways of classifying POTS have been proposed, the system that follows is clinically useful and conforms with current scientific knowledge.6

Most researchers believe that this form of POTS is often immune mediated in nature. Several studies have demonstrated that patients with postviral POTS have serum autoantibodies to α3 acetylcholine receptors in the peripheral autonomic ganglia.13 Other autoantibodies await identification. Recent studies have suggested a link with mitochondrial disorders, which might also be immune mediated. Other etiologies most likely exist as well.

One subtype of the partial dysautonomic form of POTS appears to affect adolescents, a group labeled as developmental. The usual age of onset is approximately 14 years and often follows a period of rapid growth.14 Symptoms reach their peak at approximately 16 years of age. Symptoms of orthostatic intolerance, and often migraines, may be of such intensity that the patient is disabled. Symptoms will often fade over the ensuing years, so that by young adulthood (19 to 20 years of age) approximately 80% will have experienced a significant recovery. The etiology here remains unclear, but is believed to reflect a transient period of autonomic imbalance that can occur in rapidly growing adolescents.

A second and much less common type of primary POTS is referred to as the hyperadrenergic form,15 in which patients tend to report a more gradual and progressive onset of symptoms. They will often complain persistent tachycardia, tremor, hyperhidrosis, and anxiety. Patients frequently complain of always feeling “too hot.” The distinguishing characteristic of this group is an orthostatic hypertension that occurs in addition to a postural tachycardia. A large number of these patients complain of migraines, and some will report a significant increase in urinary output after only brief periods of upright posture. Most will display exaggerated response to isoproterenol infusion. Many patients with hyperadrenergic POTS will have significantly elevated serum norepinephrine levels (>600 ng/mL) during upright posture.

There is sometimes a family history of the disorder, of which there are possibly two forms. The best understood subtype is a genetic disorder in which a single-point mutation causes a dysfunction in the norepinephrine reuptake transport protein that cleans and recycles norepinephrine spillover in response to a wide range of sympathetic stimuli resulting in a hyperadrenergic state that can mimic the state caused by a pheochromocytoma.16 A second type of hyperadrenergic POTS appears to be autoimmune in nature and is characterized by an abrupt onset following an acute febrile illness (presumed to be viral). This form can overlap with inappropriate sinus tachycardia syndrome. Investigators have isolated autoantibodies to β1 cardiac receptors that stimulate the sites without producing a tachyphylaxis.

The term secondary POTS is used to describe the wide variety of conditions that result in varying degrees of peripheral autonomic denervation with relative sparing of cardiac innervation.17 The most frequent cause of secondary POTS is diabetes mellitus. It can also be seen as a result of multiple sclerosis, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, alcoholism, Lyme disease, chemotherapy (with the vinca alkaloids in particular).18

A particularly noteworthy form of secondary POTS occurs in conjunction with the connective tissue disorder known as the joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS), or type III Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.19 An inherited condition, JHS is characterized by joint hypermobility, soft velvety skin with variable hyperextensibility, and connective tissue fragility. Patients will also demonstrate easy bruising, premature varicose veins, diffuse joint and muscle pain, and orthostatic acrocyanosis. Patients with JHS can develop orthostatic intolerance because of the presence of abnormally elastic tissue in the vasculature, resulting in an increased vessel disposability in response to the increase in hydrostatic pressure that occurs during orthostatic stress. This change can allow for an excessive degree of peripheral venous pooling with a resultant compensatory tachycardia. Gazit et al. reported that up to 70% of patients with hypermobility syndrome suffer from some degree of orthostatic intolerance.19a Many adolescents with the developmental form of POTS will have features of JHS.

At times, POTS is the presenting sign of a more severe form of autonomic disorder, such as pure autonomic failure or multiple system atrophy. In addition, POTS can be the presenting sign of a paraneoplastic syndrome that occurs in association with adenocarcinomas of the lung, breasts, pancreas, and ovary. It has been found that some of these tumors produce autoantibodies against postganglionic acetylcholine receptors in the autonomic ganglia, not dissimilar to those that have been found in the postviral autonomic neuropathies.20

Evaluation and Management

A careful physical examination is paramount. Blood pressure and heart rate should be obtained in the supine, sitting, and standing positions and after 2 and 5 minutes of standing. It is helpful to be able to watch the lower extremities for the appearance of mottled bluish discoloration (referred to as acral cyanosis) that reflects venous pooling. The results obtained during standing are quite variable; therefore, it is best to perform tilt table testing on most patients, because this setting is more controlled with fewer variables and with more reproducible results (i.e., better than that seen with neurocardiogenic syncope). Other tests of autonomic nervous system function could be useful in select patients with POTS as a way of measuring the degree of systemic autonomic involvement. Sudomotor function can be determined by thermoregulatory sweat testing or by assessment of skin conductance, skin resistance, or sympathetic skin potentials. Serum catecholamine levels, both in the supine and upright positions, should be obtained in patients suspected of having the hyperadrenergic form of POTS. Bowel motility studies are useful in ascertaining the degree of gastrointestinal involvement. More detailed descriptions of autonomic testing can be found elsewhere.6,21

One of the most important aspects of treatment is reconditioning,22 because it augments venous return through enhancement of the skeletal muscle pump. Many patients are often deconditioned and find that aquatic activities are better tolerated as a starting point. Recumbent bikes are also useful, as are rowing machines. The initial goal is to have the patient perform 20 to 30 minutes of continuous aerobic activity at least three times per week, as well as interspersed periods of resistance training.

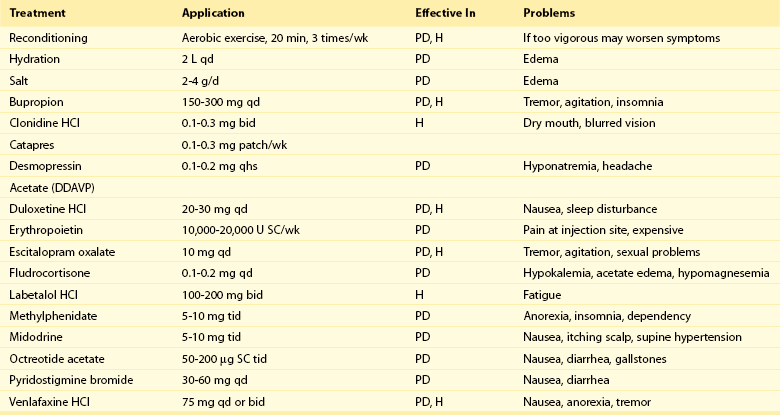

Regarding pharmacotherapy, treatment must be individualized, and is initiated with the goal of getting patients well enough to pursue reconditioning. No drug is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of POTS; therefore, any use of pharmacotherapy is done “off label.” Knowledge of the subtype is important in choosing appropriate pharmacotherapy (Table 104-1).

Table 104-1

Therapeutic Options in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome*

PD, Partial dysautonomic; H, hyperadrenergic; SC, subcutaneous.

*The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved any drug for treating postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

For the patients with partial dysautonomic POTS, therapies are oriented toward increasing fluid volume and augmenting peripheral vesicular resistance. It is common to begin with the mineralocorticoid agent fludrocortisone, which promotes sodium and fluid and sensitizes peripheral α-receptors to the patients’ own catecholamine. Oral desmopressin is also used as a volume-expanding agent. The next step is to use a vasoconstrictor such as midodrine, starting at a dose of 5 mg orally three times per day (usually with meals). Dosages can be titrated up to 15 to 20 mg orally four times per day, if necessary.20 Because patients are most symptomatic early in the morning, they are advised to take their midodrine dose approximately 15 minutes before getting out of bed. Patients are also advised that they can take an extra 5-mg dose as needed if severe breakthrough symptoms occur. The most common problems encountered with midodrine are nausea, goose bumps, and scalp itching. If midodrine is not tolerated, methylphenidate can be an effective alternative, especially because it comes in several long-acting preparations. Some investigators have also advocated the use of yohimbine.

A useful agent in managing this form of POTS is pyridostigmine, which is an acetyl cholinesterase inhibitor that facilitates neural transmission at the ganglionic level in both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves.23 Several studies have suggested a greater than 50% response rate with the agent. Doses range from 60 to 120 mg orally three times daily. Principal side effects include nausea and diarrhea.

In some patients, small doses of a β-blocker such as propranolol can be effective in controlling excessive heart rate responses to upright posture.24

In patients who have proved refractory to the aforementioned agents, therapy with injected octreotide is often attempted.25 As a potent vasoconstrictor of the mesenteric vasculature, it is administered by subcutaneous injection. Doses range from 50 to 200 µg twice daily. A long-acting form lasting 28 days is also available. Another agent used in refractory patients is erythropoietin; it augments vascular volume by causing an increase in red cell mass and seems to have direct vasoconstrictive effects. Because erythropoietin (EPO) must be administered by subcutaneous injection and because of its expense, its use is usually reserved to refractory patients.26

For patients with the hyperadrenergic form of POTS, therapies are directed at release or receptor effects of norepinephrine. β-Adrenergic blocking agents are useful, but tend to work best when combined with an α-blocking effect. Labetalol and carvedilol are useful, as is the agent nebivolol. Clonidine is an α2 receptor agonist that produces a central sympatholytic effect, and it is useful for treating patients. Some investigators have reported that methyldopa can be useful, whereas other groups have suggested that phenobarbital can help in refractory patients.15

References

1. Low, P, Sandroni, P. Postural Tachycardia Syndrome. In Robertson D, Biaggioni I, Burnstock G, Low P, Paton, editors: Primer on the Autonomic Nervous System, ed 3. UK: Academic Press/Elsevier London; 2012.

2. Wieling, W, van Lieshout, J. Maintenance of postural Normotension in Humans. In: Low P, Benarroch E, eds. Clinical Autonomic Disorders. ed 3. Baltimore, Md: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2008:57–67.

3. Streeten, DH. Orthostatic intolerance: a historical introduction to the pathophysiological mechanisms. Am J Med Sci. 1999; 317(2):78–87.

4. DaCosta, JM. An irritable heart. Am J Med Sci. 1871; 27:145–163.

5. Lewis, T. The Soldier’s Heart and the Effort Syndrome. London, UK: Shaw & Sons; 1919.

6. Grubb, BP, Calkins, H, Rowe, P. Postural tachycardia, orthostatic intolerance and the chronic fatigue syndrome. In: Grubb BP, Olshansky B, eds. Syncope, Mechanisms and Management. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2005:225–244.

7. MacLean, AR, Allen, EV, Magath, TB. Orthostatic tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension: defects in the return of venous blood to the heart. Am Heart J. 1944; 27:145–163.

8. MacLean, AR, Allen, EV. Orthostatic hypotension and orthostatic tachycardia: treatment with the “head-up” bed. JAMA. 1940; 115:2162–2167.

9. Schondorf, R, Low, P. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: an attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia? Neurology. 1993; 43:132–137.

10. Low, P, Opfer-Gehrking, T, Textor, S, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome. Neurology. 1995; 45:519–525.

11. Khurana, RK. Orthostatic intolerance and orthostatic tachycardia: a heterogeneous disorder. Clin Auton Res. 1995; 5:12–18.

12. Karas, B, Grubb, B, Boehm, K, et al. The postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: a potentially treatable cause of chronic fatigue, exercise intolerance, and cognitive impairment in adolescents. PACE. 2000; 23(3):344–351.

13. Vernino, S, Low, P, Fealey, RD, et al. Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343:847–855.

14. Grubb, BP. The postural tachycardia syndrome: when to consider it in adolescents. Family Practice Recertification. 2006; 28(3):19–30.

15. Kanjwal, K, Saeed, B, Karabin, B, et al. Clinical presentation and management of patients with hyperadrenergic postural tachycardia syndrome: a single center experience. Cardiol J. 2011; 18:527–531.

16. Shannon, JR, Flatten, NL, Jordan, J, et al. Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine-transporter deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:541–549.

17. Nankiewicz, K, Somers, V. Chronic orthostatic intolerance: part of a spectrum of dysfunction in orthostatic cardiovascular homeostasis? Circulation. 1998; 98:2105–2107.

18. Kanjwal, K, Karabin, B, Kanjwal, Y, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome following Lyme disease. Cardiol J. 2011; 18(1):63–66.

19. Kanjwal, K, Saeed, B, Karabin, B, et al. Comparative clinical profile of postural orthostatic tachycardia patients with and without joint hypermobility syndrome. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2010; 10(4):173–178.

19a. Gazit, Y, Nahir, A, Grahme, R, et al. Dysautonomia in the joint hypermobility syndrome. Amer J Med. 2003; 141:421–425.

20. Grubb, BP, Kanjwal, Y, Kosinski, D. The postural tachycardia syndrome: a concise guide to diagnosis and management. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006; 17:108–112.

21. Grubb, BP. The postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation. 2008; 117(21):2814–2817.

22. Fu, Q, VanGundy, T, Shibata, S, et al. Exercise training versus propranolol in the treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome. Hypertension. 2011; 58:167–175.

23. Kanjwal, K, Sheikh, M, Karabin, B, et al. Pyridostigmine in the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia: a single center experience. PACE. 2011; 34(6):750–755.

24. Raj, S, Black, B, Biaggioni, I, et al. Propranolol decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation. 2009; 120:725–734.

25. Kanjwal, K, Saeed, B, Karabin, B, et al. Use of octreotide in the treatment of refractory orthostatic intolerance. Am J Ther. 2012; 19(1):7–10.

26. Kanjwal, K, Saeed, B, Karabin, B, et al. Erythropoietin in the treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome. Am J Ther. 2012; 19(2):92–95.