Postpartum problems

Physiological changes

Genital tract

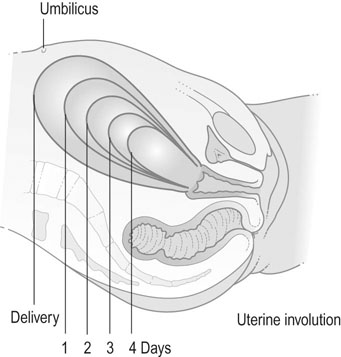

The uterus weighs 1 kg after birth, but less than 100 g by 6 weeks. Uterine muscle fibres undergo autolysis and atrophy and within 10 days the uterus is no longer palpable abdominally (Fig 13.1). By the end of the puerperium, the uterus has largely returned to the non-pregnant size. The endometrium regenerates within 6 weeks and menstruation occurs within this time if lactation has ceased. If lactation continues, the return of menstruation may be deferred for 6 months or more.

The importance of breastfeeding

Colostrum

Breastfeeding

The breasts and nipples should be washed regularly. The breasts should be comfortably supported and aqueous-based emollient creams may be used to soften the nipple and thus avoid cracking during suckling. Suckling is initially limited to 2–3 minutes on each side, but subsequently this period may be increased. Once the mother is comfortably seated, the whole nipple is placed in the infant’s mouth, taking care to maintain a clear airway (Fig. 13.2). Correct attachment of the baby to the breast is essential to the success of breastfeeding. The common problems such as sore nipples, breast engorgement and mastitis usually occur because the baby is poorly attached to the breast or is not fed often enough. Most breastfeeding is given on demand and the milk flow will meet the demand stimulated by suckling. Once the baby is attached correctly to the nipple, the sucking pattern changes from short sucks to long deep sucks with pauses. It may, on occasions, be necessary to express milk and store it, either because of breast discomfort or cracked nipples or because the baby is sick. Milk can be expressed manually or by using hand or electric pumps. Breast milk can be safely stored in a refrigerator at 2–4°C for 3–5 days or frozen and stored for up to 3 months in the freezer.

Complications of the postpartum period

Puerperal infections

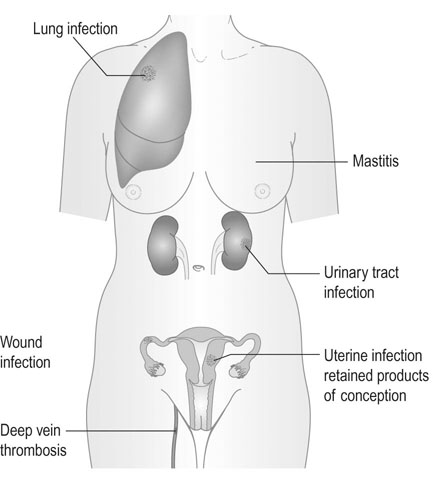

Puerperal sepsis has been reported as far back as the 5th century BC. The Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE 2006–2008) has highlighted the re-emergence of sepsis (in particular group A β-haemolytic streptococci) as a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the UK. Other common causes of infection are urinary tract infections, wound infections (perineum or caesarean section scar) and mastitis (Box 13.1 and Fig 13.3).

Maternal collapse

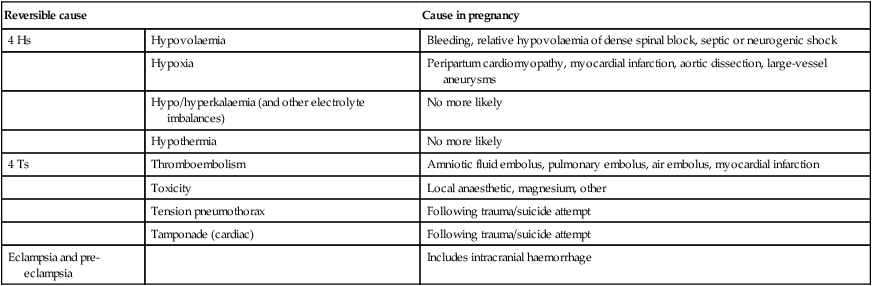

There are many causes of collapse, and these may be pregnancy-related or result from conditions not related to pregnancy and possibly existing before pregnancy. The common reversible causes of collapse in any woman can be remembered using the 4 Ts and the 4 Hs employed by the Resuscitation Council (UK) (Table 13.1). In the pregnant woman, eclampsia and intracranial haemorrhage should be added to this list.

Table 13.1

Reversible causes of collapse in pregnancy/postpartum

| Reversible cause | Cause in pregnancy | |

| 4 Hs | Hypovolaemia | Bleeding, relative hypovolaemia of dense spinal block, septic or neurogenic shock |

| Hypoxia | Peripartum cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, large-vessel aneurysms | |

| Hypo/hyperkalaemia (and other electrolyte imbalances) | No more likely | |

| Hypothermia | No more likely | |

| 4 Ts | Thromboembolism | Amniotic fluid embolus, pulmonary embolus, air embolus, myocardial infarction |

| Toxicity | Local anaesthetic, magnesium, other | |

| Tension pneumothorax | Following trauma/suicide attempt | |

| Tamponade (cardiac) | Following trauma/suicide attempt | |

| Eclampsia and pre-eclampsia | Includes intracranial haemorrhage | |

(Reproduced from Maternal Collapse in Pregnancy and the Puerperium. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecology Green-top Guideline No. 56, January 2011.)